Courtesy Ingleby Gallery

Duncan Ellstrom

Fourth of July, 1895

The ferry was coming special because it was the Fourth of July. Some of the kids from school were there but I stayed apart from them and threw handfuls of sawdust into the water and watched it drift and spiral and sink. Ben and Joseph McCandliss showed up and no one wanted to play with them, either. They were orphans now since their father had been sent to the penitentiary in Seattle. I remembered when my father left me and Mother when I was little. He came back but he still wasn’t around very often. Mother sometimes called him the boarder. Ben and I were both eleven years old and would be in the same class if Ben went to school. Joseph was fourteen and had already, more than once, spent the night in jail. Miss Travois had taken them in but I’d heard they didn’t sleep there, they just did whatever they liked. Wharf boys, we’d all been warned against them.

“We ain’t waitin’ for the boat,” Ben said to me, climbing up into the lumber cribs to be with his brother. I was too scared to go up there with them so I went back to the water and threw some more sawdust.

It’d been an hour at least already and everyone had cleared off somewhere to sit among the shingle stock. The mill was shut down for the holiday. I’d never seen it like that, and it was like when I saw the dead horse because I’d never seen that either. The doorway was filled with the smell of my father, grease and kerosene and sawdust. He wouldn’t be here today, off working, always. Didn’t see him much but I’d got used to that.

My mother called to me but I stopped my ears with my fingers so I couldn’t hear her. I took one step forward, waited, and then kept going. The blood was pumping in my ears against my fingertips like I was under water. The mill floor had been swept and I could see the broom marks and where they piled and scooped up the dust. It was cool and silent inside and crammed with machinery. I’d heard the mill sounds for as long as I could remember. It was strange, it being so quiet. I thought: I’m a little machine and when I go silent I’ll be silent and I’ll be dead.

A drive shaft connected to the ceiling followed the main roof beam the length of the building. Attached to it were flywheels of various sizes, all six-spoked. I counted them twice. Drive belts a foot wide stretched like taffy to the machines below. The wheels on the pony rig were caked with resin and didn’t want to spin when I tried them. I touched a steam pipe but it was cold. The boiler was far off, all the way on the other side, visible from the road but not from where I was. Someone was moving around in the back of the building, banging on something. There was the weak light of a lantern climbing up the wall behind the edger. I went forward to hide and put my hand on a flywheel that was taller than me and kind of hugged it and put my feet in the spokes and it felt good in my arms, big and solid, heavy and round and perfect. I scraped my fingernails over the belt and felt so peaceful, so content.

“What’re you doin’ there, boy?”

I jumped down at the sound of the voice and ran for the door, ran right into my mother’s legs. She had me by the shoulder and led me back to where her bag was and sat me down on a bolt of shingles. And there we stayed. Bored as I’d ever been.

Each time I looked up there were more people. Most of them were families with fathers carrying the burdens of a picnic, but there were bachelors too; roamers, mill workers, loggers, and they filled in the cracks in the crowd and bunched up in knots around bottles and the few lonesome women with no families. I’d never been on a real steamship before, an oceangoer. I’d heard their birdy whistles and watched them move up and down the river but I’d never even touched one up close. The other children at school hadn’t been born in the harbor so they’d arrived by steamship and knew all about them and how fast they went and how far, to China and everywhere.

My mother was chatting with some of the women she knew from the bakery but I stayed silent and waited and when I saw my chance I snuck back to the water’s edge and threw sawdust and splinters into the murky, slick, little boats that didn’t sink as long as I watched them. When the whistle blew I jumped, but I wasn’t the only one, and people laughed. It was just the stupid ferryboat that I’d been on a hundred times. They’d said it would be some other special ship for the Fourth.

Me and my mother were ushered up the gangplank and helped down to the shining deck by the deckhands. They were wearing special white and blue uniforms with shiny silver buttons.

“Hello, Mrs. Ellstrom. Welcome aboard, son.”

Yer a dopey dimwit and a slint-faced turd. I silently practiced my insults like I’d sharpen a knife.

A month ago I’d been different or at least unseen.

Mother chose a place at the stern rail and I watched to see who else would board because not everyone would fit. I’d been getting teased at school and it had made me cagey. Donald Church was the worst and he was in line with his family waiting to board but they were too far back and had to wait. A month ago I’d been different or at least unseen. The story of the ugly duckling told me that it was better before knowing, so maybe it would be better later too. But for now I was scared all the time that someone would yell at me, some older boy like Donald would pick on me.

The lines cast off. People were talking and laughing all around. The whistle blew and I could feel the engine in my feet. Once we were away from the shore I slipped down the rail to look around. The boat was full of women and children. All the loners and Donald and the other complete families were watching us leave. I waved and people waved back, even Donald. Deep water off the rail, below, perilously dark.

“Why’re we goin’?” I asked Mother, just to irk her, to get her talking to me.

“You like the Fourth.”

“I guess so.”

“Don’t get in a mood already, and try to stay close. I don’t want to have to spend the whole day looking for you.”

“Will it be cold?”

“Not much colder. There will be wind.”

“Can we see whales? Zeb said his dad took him fishing and they saw whales.”

“Maybe from the beach. We won’t be on the water.” She adjusted her hat and smiled, three small moles on her left cheekbone, a constellation. “I’m glad you and Zeb are friends.”

“Course we’re friends. We’re best friends. I’m smarter than him.”

“Why would you say that?”

“Because I can make him do what I want.”

“That’s not the way you should think of your friends.”

“Why?”

“It’s important to care for people. To be kind.”

“I’m not mean to him. People are mean to me.”

“They’re just teasing. Don’t let them bother you.”

“I don’t care.”

“Of course you don’t.”

“But sometimes I care.”

“They’ll give it up. You’ll see. You just need to outlast them. Don’t let them get under your skin and don’t let them know when they do.”

Easy for her to say. She was pretty, everybody said so. Everybody watched her. She had her hand on my shoulder and I leaned against her and felt the boat roll.

We passed log booms and shacks and slash fires, newly built and painted houses and shops, bright and streaky with colors that seemed to run into the air and leach into the mud.

We docked at the mill pier because that’s where the ferry always stopped. We got off and went along the plank road to the wharf where the real holiday steamers were assembled to take us to the beach. Ribbons and streamers were everywhere. Sleek, shining ships filled the harbor. People crowded the streets. I could smell the bakery even though it was closed. We used to live here when I was a baby. I don’t remember much of that time. Mother was looking off up the hill toward the middle of town where the buildings were biggest. The bakery was too short and low to see with everything else in the way.

There were dozens of children from other schools and I didn’t know any of them by name. My mother pushed me toward them but I spun around and hid behind her stiff muslin skirt. Some of the boys had hats and I wanted one. Mother had her hair up and her plaid blouse was ironed and flat. She carried a canvas bag with our lunch and extra coats. Little girls with braids and white dresses held hands and ran in circles on the wharf.

The ship we were to board was decked in blue bunting like the rest. A band was marching in the streets of town, and after boarding, a band set up in the bow and started right in and the band onshore stopped their song and waited, and then joined in with the band on the boat. We stood at the rail in the stern of the steamer and watched the wake. It was loud with the two streams of music and the wind and everybody talking and crowded and I was ready to get off. The ship was just like the ferry, no different. The wake was just the same, only bigger. We weren’t going any faster. Steel was colder and somehow just as slimy as wood.

I thought of pirates and deserted islands, solitary endeavors, days and eventually years surveying an isolated and foreign land…

“Stop that,” Mother said.

“What?”

“You’re moping.”

“I’m not.”

“You are. There’s a rumor that a ship is beached on the coast.”

“A shipwreck?”

“Yes.”

I thought of pirates and deserted islands, solitary endeavors, days and eventually years surveying an isolated and foreign land, surviving, prospering, escaping heroically, a flash of genius and daring; upon my return a celebration not unlike the Fourth. My mother let me read by the fire before I went to bed and I had the stories in my head always.

Gulls passed through the smoke from the stack. I’d had an apple after breakfast on the way to town earlier but I was hungry again. The mist covered the hills and blocked the openness of the coast. The carts of clam diggers dotted the shoreline, their shadowy figures working the tide, ebb harvesters. Pelicans and their sagging bags. The grass on Rennie Island was flattened by the wind and the trees all leaned after it, giving needles and leaves, whatever they had. A boy climbed onto the rail and his mother tugged him back down by his pants and gave him a whipping. I wanted to run away but there was nowhere to run.

Mother was speaking to a man in a bowler. It wasn’t anyone that I’d seen before. She told me we’d be seeing Dr. Haslett today but it wasn’t him—they wore the same hats is all. We hadn’t seen Dr. Haslett for a long time and I rarely thought of him anymore. This man had a mustache and a big nose and he was big, much bigger than Father. His gray suit didn’t fit him and it was too tight to button over his chest. He smelled strongly of vinegar and his fists hung out of the inadequate sleeves like kneaded dough that had been left on the board to dry out. His mustache was red and black and gray and so was the curly hair sticking out from under his hat. Mother caught me staring and introduced the man as Mr. Tartan, a friend of Mr. Bellhouse’s from the Sailor’s Union. He took my hand in his and squeezed until it hurt and wouldn’t let go. The pressure didn’t increase but it didn’t let up.

“He’s grown tall, hasn’t he?”

“He has,” my mother said.

“Give me my hand back.”

“I’m not holdin’ you at all, hardly squeezin’. Go and take yer own hand.”

“It hurts.”

“Let him be, Lucas.”

The man let me go and I held my hurt hand with my other one.

“I was playin’ with him, Nell. I wouldn’t-a hurt him.”

“You’re scaring him.”

“I wasn’t scared.”

“Ready to piss yer pants, you toughy slint.”

“I wasn’t.”

“It’s all right, Duncan,” Mother said.

“I’m not scared-a him.”

He leaned down and spoke: “A folly of youth is what that is.”

The ship chugged on and I turned toward the sea and watched the gulls and thought I saw a seal but wasn’t sure. There had better be whales and sharks too. My hand hurt. We went by Sentinel City with its dock practically halfway across the harbor. No one was there, not a soul. The whole project had been abandoned. The hills were logged to the water line and plotted for streets and graded for a railroad but none of it ever came. Father had worked there and had helped build the dock. We’d almost moved because he was offered land instead of pay but Mother wouldn’t let him take it. She liked our place and told me Uncle Matius no longer had any claim. I didn’t remember my uncle at all. They said I had a cousin too.

Mr. Tartan’s big hand reached over my shoulder and patted me on the chest. I turned to see his face but the sun was in my eyes. Something tapped me on my chin and I looked down and there was a silver dollar resting in the folds and calluses of Mr. Tartan’s hand. He leaned over and whispered with vinegar breath. “Take it, boy. Hard currency to remind you of our independence.” His breath was hot in my ear.

I took the offered coin and quickly tucked it into my vest pocket.

“Good. Keep it safe.”

“What’d you give him?” Mother asked.

“Between me and the boy.”

“Let me see, Duncan.”

“Don’t show her. Keep it private. Me and you.”

And I didn’t show her. I kept it hidden.

Long before we arrived at Westport, Mr. Tartan had disappeared back into the crowd. I followed Mother down the gangplank and onto the pier. The high clouds and mist were burning off even at the coast and the sun would be out soon. The slow-moving crowd went on like a funeral procession. I couldn’t see anything but legs and backs and hands. Mother kept a tight grip on the collar of my coat. We fell in with a group of women and their children and to my wonderment one of them was Zeb Parker. He was supposed to be at home watching his new baby sister but his mother was with him and she had the baby in her arms.

“Thought you’d have it to yourself, didn’t you?” Zeb said, grinning.

I smiled at him but didn’t say a word. I always felt lonely and I regretted what I’d told Mother about being smarter than Zeb. The best thing that’d happened to us was the Parkers moving in down the road.

We went through the trees to the veterans’ grounds where tables were set up among the cabins and tents. A band was playing. We found an open place and spread a blanket and had lunch. Me and Zeb finished our chicken legs and then ran off. Everyone was dressed up and smiling. The sun was out now and the cedar grove was golden and warm and the wind couldn’t get at us. I ran through the crowd with Zeb behind me and shoved people in the legs to get them to move. Cedar needles covered the ground and we got pitch all over our hands and pants crawling and wrestling and later trying to climb the trees and their yarny trunks. I could smell the salt of the ocean like a cooked meal drawing me in. Mother was yelling for me, Duncan you come back here Duncan. I laughed and smiled at Zeb and we ducked low and used the crowd for cover and snuck into the madrones.

It was like a gift given to me, that ship. I couldn’t be happier if it were my birthday.

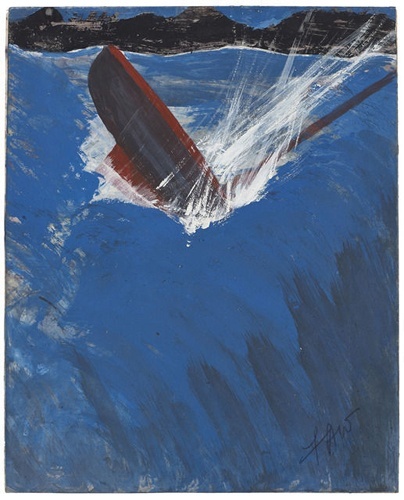

We followed a sand path out of the trees and over the bluff and stopped dead in our shoes when we saw the open water. Bigness required boundaries but this water had none save the shore we stood upon and the end of my eyeball’s reach. It looked like the end. There were more people on the beach, all down it to where the shipwreck sat askew, not so big, and so fragile. It was like a gift given to me, that ship. I couldn’t be happier if it were my birthday.

As the sand hill sloped away, it lost its grass covering and flattened into low dunes and beach. It went on for as far as I could see. I knew from Mother’s books that we weren’t anywhere but in a corner of the big world. Like the corner of the corner tack room in the barn, where the boards met and made a poor joint and in the void was the spider nest, that’s where we were. Outside the ocean. I shouldn’t have left Mother alone, even though Big Edna Parker was with her, but that man Mr. Tartan, she called him Lucas, he could come back and bother her. He seemed bothersome, like a bear in a trash pit. I touched the coin in my pocket. Zeb was ripping the flowering heads off a handful of seawatch. When he was done, he smelled his fingers and made a face.

A black dog ran up and jumped and licked me in the face and ran off, so we chased it and played with it until we were at the shipwreck with everyone else. She was a twomasted schooner sunk in the sand like a piece of driftwood called the Nora Harkins. The crew was still on her taking down the rigging and some men from town were on the ground, heckling. Wind blew us and the birds and everything around, gulls hung like twin-bladed arrow punctures in the sky.

“If you’d done that first, you wouldn’t be the main attraction here, eh?” The man on the ground took a pull from his bottle, looked at his friend. “Sailors are slint-fuckin’ dumb.”

“You won’t be thinkin’ that when I split your fuckin’ head with a marlinspike.” The sailor was coiling line, and he was fast, never slowed. He belonged in the mill with the rest of the machines.

“So says the bushy-tailed squacker. Landlocked.”

“Most ships,” his acquaintance said, “they go in through the harbor mouth.”

“You don’t say.”

“It’s true. They seem to perform better when they stay where the water is. Wetness seems to aid the travel of a ship.”

“They require great wetness.”

The drunks couldn’t control their laughter, and one of them fell over. “Fourth-a fuckin’ July, and you—fuck, stop it. You’re killin’ my fuckin’ insides. Fourth-a fuckin’ July.”

“Would you shut up?”

“There’re children listening.”

“Oh, so there is. Sorry for the language, boys, but let this be a lesson on careers. Don’t be a squackin’ beach-dwellin’ dipshit of a sailor when you come of age. Be anything but that.”

“Ignorant stinking loggers. Every last one of you is bone stupid.” The sailor dropped the coil to the beach with the rest of the gear. “And I’ve seen the world, I know stupid when I see it. You, gentlemen, are world class. Congratulations.”

“Thanks, squacky. Thanks so much.” The heckler had given up all hope of control, and he convulsed and kicked his legs, tears streaming down his face, laughing harder than I’d ever seen a man laugh. I was amazed. I went and stood over him, smiling, not believing what a spectacle he’d allowed himself to become. But suddenly he came to his senses and locked his eyes on me and kicked at me and hit me in the stomach and it hurt to breathe.

“The fuck you starin’ at, you little goon?”

I retreated, and Zeb followed, nervous and quick-footed. A woman called to us to stop and then scolded the drunks and forgot about us, so I turned and headed down the beach, holding my stomach and crying a little; it felt like I needed to go to the bathroom or breathe. It hurt, but running made it better, and the beach it went until Alaska or California or somewhere and there were other dogs to play with up ahead. Zeb caught up with me and we found dungy crabs in a singular rocky crag tide pool and messed with them and stacked them on top of each other and tried to get them to fight. If we guided them, they’d lock their pinchers on one another and we could lift them in a string. I tossed the string at Zeb, but it flew apart in the air.

I stood and dropped the stick and then picked it up again and threw it off toward the surf. I hadn’t meant to hurt him, but he was hurt.

A boy and a girl close to our age arrived and wordlessly joined in. The boy and his sister—had to be his sister, they looked so alike—ran off for a moment and came back with sticks and beat the crabs and smashed some of them. I took the stick away from the boy, twisted it loose from his hand, and we both fell backward.

“Give it back,” the boy said.

“Give him his stick,” his sister said.

“Catch me and I’ll give it to you.” I got to my feet and was off. Me and Zeb were much faster than them. The boy was fat and ran stiff-legged and slow. Far down the beach I spotted something black and lumpish on the sand and ran to it but it was just kelp. We stomped the bulbs but they were tougher than they looked and caused us to slip. Zeb climbed on top of the pile and bounced up and down.

“Pretend it’s a whale.”

“Been killed,” I said. “By a shark with teeth like this.” I held up the stick in my hands to show him the great size of the teeth. And it was then that the boy tackled me and knocked me down and hit me in the shoulder with a hunk of driftwood. I spun around and swacked him in the face with the stick in my hand and the boy fell backward, covering his eye. I stood and dropped the stick and then picked it up again and threw it off toward the surf. I hadn’t meant to hurt him, but he was hurt.

“Are you all right?”

“You hit my eye.”

“Is it bleeding?”

“Get away from him,” his sister said.

I did as I was told. She was pretty and neat, like a doll was neat, even if she did sort of look like her brother. “Sorry,” I said.

“C’mon,” Zeb said. “Leave ’em here. Let’s go.” Then he ran off without waiting for me.

The girl helped her brother to his feet. He wouldn’t uncover his eye for her to see it. I’d hurt him and didn’t want to get in trouble for it. I dug the silver dollar the man on the ferry had given me out of my pocket and shoved it into the boy’s hand and then ran away as quickly as I could. The girl called after me to wait, but I didn’t slow down.

When I finally caught up with Zeb, he had a hole going in the sand and had already hit water. Somebody was shooting a pistol down the beach. Dogs barked and barked. There were no whales. The wind made you feel like you’d just fall over if it were to stop. The brother and sister were as tiny as birds way down the beach, walking, shimmering away or toward us, I couldn’t tell. It was time to go. The waves were breaking far offshore, and the sound was part of the wind, like the band had been parts of a song. The sun was in the spot that told me I needed to go. I watched Zeb run off and didn’t say a word to stop him. People were hanging a swing from the bowsprit of the shipwreck. A man hung from it by one arm and set his loops, and then dropped to the hard sand.

When I returned to the veterans’ grounds, Mother gave me a cheese and onion sandwich. My shoes were full of sand, and my eyes were watery from the wind and sand, but it was quiet on this leeward side of the swale. Mother and Edna were sitting on the blanket spread on the ground and sharing a bottle of beer.

“Where’s Zeb?” Edna asked.

“He’s on the beach.”

“Why didn’t you stay with him?” Mother asked.

“Didn’t feel like it.” I turned my back on them and wandered through the trees with my sandwich and watched the crowd. Long tables were set up and the veterans, some in uniform, were getting their food first while everyone else cheered and clapped. I recognized some of these men and it was only today that anybody put up with them or encouraged them in any way. Two dogs were stuck together, and a woman in a green dress was smacking them with a stick to get them apart. People were laughing at her and trying not to look.

I sat down next to my mother on the blanket. I was tired and wanted to lie down. Edna poured me a bit of beer into a jar that had pickles in it before and I took it and drank it. I offered up the empty jar for more.

“That’s enough.”

I smiled thinking of the surprise waiting for all the picnickers when they crested the swale. They’d have sand in their teeth, packed into their gums like a dog that’d been eating horse turds.

I set the jar down and lay back and studied the fuzzy low limbs of the cedars. The band marched by playing some kind of waltz and the veterans were behind them with their plates full of food. They thought they wanted to go and eat on the beach but they were wrong. Somebody should tell them. But they knew, they all knew what they were doing. The man that had kicked me knew. I smiled thinking of the surprise waiting for all the picnickers when they crested the swale. It would blow the food off their plates. They’d have sand in their teeth, packed into their gums like a dog that’d been eating horse turds.

The sun was lower and there were clouds. Mother was gone, and so was Edna. Everyone was gone. I had a blanket on me, and I didn’t know how long I’d been asleep. The tables were no longer set, and the chairs were stacked up under the trees. I hurried to my feet and ran toward the beach. The wind knocked me back, and it took me a moment to realize that there was no one there. The shipwreck was there, but that was all, driftwood and the shipwreck but no people. I stayed on the swale and held my hands out to touch the tall grass and walked north toward the harbor mouth. Maybe the ferryboats had come and Mother forgot me. I thought I should go back, and then far up ahead I saw something on the beach. As I ran, the waves sucked at the sand and the wind blew foam at me, bubbles racing, birds pecking at the sand, fat as turkeys. It was a group of people gathered around something big and gray, not a rock, not stone. I lowered my head and ran as fast as I could down to the hard-packed wet sand, and I could go really fast there and jump the slick waves and foam and the driftwood.

I’d gotten my whale. It was a finback and it was dead, but I’d wanted to see a whale and I did. Mother saw me and came over and put her arm around me.

“It’s terrible.”

“You left me.” I had yet to catch my breath.

“You’re old enough to wake up alone and not be scared.”

“But I didn’t know where everybody went.”

“You found us, that’s all that matters.”

The bugle player from the band started on some mournful song but someone yelled at him to shut it and he stopped. The big man, Mr. Tartan, was there and he didn’t look nearly as sad as everyone else. A few of the drunken soldiers looked like they might weep, like the whale had been their friend, like the holiday was for it instead of them. People were touching the whale’s hide, petting it. A group of Indians, three boys and two grown women, were on the hill watching us. Mr. Tartan stood apart from the crowd and watched them back, and then he turned and wandered in the direction of Westport.

I found Zeb at the tail with some other boys digging out the sand from beneath it. I found a stick and joined in. The tail would soon be the roof of our fort. My pants and shoes were soaked through from the seeping sand.

The man that had kicked me found me down in the hole with the other boys. “Did you hear me, boy? I said I’m sorry I was rough with you before.”

“It’s okay.”

“I didn’t mean to scare you. I didn’t hurt you, did I?”

“No. I’m fine.”

“All right.” The man joined his friends and as a group they returned to the shipwreck. He was walking with some of the sailors.

“Duncan,” Mother said. “It’s time we get going if we don’t want to be left behind.”

“Come on out of there,” Edna said to Zeb. “I don’t want to hear you complaining about being cold on the way home.”

“I won’t,” Zeb said as he climbed out.

I was right behind him. “What’ll happen to the whale?” I asked my mother.

“It’ll rot, I’d guess. Maybe if there’s a storm it’ll get carried out to sea. The birds will be after it as soon as we leave, I know that.” She looked up at the Indians but didn’t say anything else.

The walk back to the wharf was tiresome and cold and the wind was everybody’s enemy. The boy I’d fought with earlier was being helped along by two women. His sister pointed me out to them. Mother and Edna stopped to ask if they needed help and the boy told on me.

“Is this true?” Mother asked.

“I didn’t mean to hurt him,” I said.

“He started it,” Zeb said. “He hit Duncan first.” Right then Edna’s little baby started to cry so her and Zeb had to keep walking. We’d see them at the wharf. I waved goodbye to him because I was on my own now.

“Don’t see how it matters who started it,” one of the women said. “His eye’s a mess.”

“He needs to see the doctor,” the other woman said.

“Are one of you his mother?” Mother asked.

“No, ma’am, the Boyertons are in Seattle. We’re watching the children for them.”

Mother knelt down in front of the boy and pulled his hands away from his face. There was a bruise above his eye, and the eye itself was blood-red and teary. He couldn’t hold it open without crying.

“What’s your name?”

“Oliver.”

“Oliver. And is this your sister?”

“Yes.”

“What’s her name?”

“Teresa.”

“Hello, Teresa.”

“Hello.”

“Are you going to be all right?” Mother asked the boy.

He shook his head no. “My eye hurts.”

“I know it does. I know. Duncan, apologize to Oliver for hurting his eye.”

“It was an accident,” the little girl said. She was staring at me like she knew me.

I felt the blood go hot into my face. I could tell she wanted to say something else, something mean that would hurt me but she couldn’t with my mother there. Oliver had his hands back over his eye and the two women ushered him on.

“Say goodbye,” Mother said.

“Bye.”

“Bye,” the girl said to me.

We heard the whistle and everybody hurried but we were too late. I could see Zeb and his mother at the stern waving to us. Everybody was waving. We waved back because what else was there to do and watched them until they were gone. The water boiled white and the wake sloshed out in a V and rolled white-edged a few times and then went to waves and then healed completely to blue water. The smoke from the stack caught the wind and was gone, like steam in a warming room. People said it’d be an hour for the next one to come. Mother and I found a good stump out of the wind to sit on and wait. The boy and the girl and their keepers stayed on the other side of the crowd from us. I didn’t see them again until we got to town. The clouds rolled in and blocked all of the sun.

Father was at the docks when we arrived. He was falling-down drunk and covered in mud. He’d lost his hat.

While we were filing up the plank the rain started again and everybody grumbled, but when I looked back at my mother, she was smiling. We found our spot and she tucked me in against her side and we were off. I slept and missed seeing everything again.

Father was at the docks when we arrived. He was falling-down drunk and covered in mud. He’d lost his hat. We couldn’t do anything with him. He tried to hug me and knocked me over and I had to fight my way out of his arms. Mother pushed him back and was embarrassed, and the women she’d been speaking with when we docked looked away. The girl and the boy, Teresa and Oliver, went by and stared, and my face burned with shame. It was Mr. Tartan that hauled my father to his feet and dragged him up the mole to the Sailor’s Union. We waited outside and when Mr. Tartan returned he took Mother aside and spoke to her. He touched her shoulder and bowed slightly and went back inside.

“We’re going home.”

“What about—”

“He’ll stay here. Mr. Tartan has given him a bed for the night.”

“The fireworks will start soon.”

“We’ll be able to see them on our way. From the water. You’ll see.”

She took my hand, and we walked the crowded streets toward the wharf. There were stages set up and music was being played and there were jugglers and a man on a unicycle. I watched a family of Indians walking up the hill into the logged forest until they disappeared into the slash. A man rode by us with his eyes closed and fell off his horse and another horseman ran him over. Mother didn’t let me stop, not once, and soon we were back on the ferry that would take us home. The deckhands’ uniforms had lost their luster, and they all looked tired. They lit the lights on deck and we headed out in the gloom of the evening. We’d left the celebration behind.

My mother turned to me and held me by the shoulders. “I don’t want you to ever feel like you’re responsible for your father.”

I nodded, but I didn’t understand.

“He did that to himself. He doesn’t do it to hurt us. He does it because he’s no self respect. That isn’t your fault.”

“Will he come home tomorrow?”

“I doubt it.”

“He peed himself.”

She stopped rubbing my shoulders and held me still. “I need you to understand something,” she said. “There are choices you’ll make that will determine where you end up. Often you’ll make bad decisions and regret them. Do you understand me?”

“Yes.”

“Don’t lie to me. Don’t ever lie to me.” I could feel her hands shaking, and her eyes were filling with tears.

“I’m not lying.” But I was. She wanted me to, she’d cry if I didn’t.

“No matter what happens, where you are,” she said, “you get to choose how you act. In the end that might be all the choice you’ll ever get, but it’s a lot. It’s more than most people can handle.” She hugged me and held me close, and I could feel the ferry’s engine all through my feet and into my legs.

The sound was a crack like a gunshot but too open-sounding to be a rifle or even a shotgun, and when we turned from each other I saw the spray of red and green fireworks splash against the wet sky.

Excerpted from The Bully of Order by Brian Hart, to be published in September by HarperCollins.

Brian Hart was born in central Idaho in 1976. He’s worked as a carpenter, welder, drywall hanger, dishwasher, commercial fisherman, line cook, and janitor. In 2005 he won the Keene Prize for Literature, the largest student literary prize in the world. In 2008, he received an MFA from the Michener Center for Writers. Hart currently lives in Austin, Texas, with his wife and daughter. The Bully of Order is his second novel.