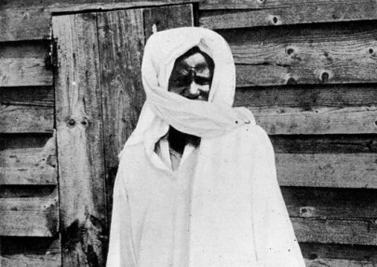

The only known photograph of Amadu Bamba was taken in 1913, but you can’t see him in it. Or rather, you can see him, but only by suggestion. The French colonial authorities had placed him under house arrest in Diourbel, Senegal, and the framing of the picture has the naïve objectivity of a mug shot. In the background are the knotted plank walls of a mosque and at the bottom are the jagged contours of rocks and sand, but at the center is a puzzling absence, where the searing white of Bamba’s robe seems to have burned away the celluloid. Left behind are molten puddles of film where his face and feet should be.

Amadu Bamba was a learned Sufi Muslim, a popular teacher, and a wali Allah, a “friend of God,” a saint. Sufis dedicate themselves to retrieving the traces of divine essence buried in the blood of human experience. They know it exists because, at the creation of Adam, God commanded his angels, “And when I have fashioned him and breathed into him of My Spirit, then fall down before him prostrate.” The Arabic word for “spirit” is the same for “breath,” and Sufis engage in marathon recitations of the shahada and dhikr (the names of Allah), the transformation of empty air into the words of divine truth, until they themselves become nothing but a continuous prayer.

Bamba was a master of words. “Thanks to the Koran, I have come into the presence of my Lord / I have mastered my soul and distanced myself from Satan,” Bamba averred in his poem “Passport to Paradise.” The evidence of his boast was in the verse. Senegalese people will tell you that the Arabic rhymes so perfectly it could only be divinely inspired. His other writings bore similar proof. Students swarmed to him. Bamba founded his own tariqa, a Sufi brotherhood dedicated to the edification of acolytes. Amadu Bamba’s disciples would not be mere pupils, tullab, but fellow aspirants, muridun, and his brotherhood became the Muridiyya.

The French, suspicious of this massive communion among subjects they did not trust seeking a God they did not know, exiled Bamba to Gabon and then Mauritania. House arrest had been a kind of reprieve. But to monitor Bamba’s movements, the French sought to fix his image, so they dispatched a man with a camera into the hinterland to catch the sage on film.

Sufi epistemology rests on the fundamental unity of zahir (the manifest) and batin (the hidden). The first is the world known to the senses. The second is the essential nature of creation known to God and revealed to his prophets and saints. Whatever the camera captured with the soft flutter of its aperture, it belonged only to the apparent world of things. The French tried to capture the Amadu Bamba they thought they wanted: the image and body of a subject. But Bamba had seen the secret universe of heaven, had articulated its mysteries in verse and channeled its power in miracles, and part of him was unseen and unknowable. The photograph was proof. You don’t see a man, but a void and a shadow, the invisible and its indication.

The Muridiyya survived Bamba and French rule, led by the grand caliphs and lesser marabouts, or Sufi religious advisers, all descendants of Bamba and therefore imbued with the divine blessing—baraka in Arabic—Bamba attained from God. The picture survived, too, reproduced in paintings, drawings, and murals all over Senegal. Every Murid hopes the image holds baraka that will bless him, too, so the saint appears everywhere: hanging in living rooms, leering from posters in open-air markets, scrawled on walls and buses.

Muslim extremists, often backed by fundamentalists in the Middle East, have violently subjugated Sufis to jihad as far south as Nigeria…. In the lingering dusk of such violence, Senegalese Sufism appears once again as a faith of possibility, the potential for a popular, democratic Islam.

These images were Bamba as I found him in the streets of Dakar. His picture competed with the graffiti left over from Senegal’s presidential election last spring. The incumbent, Abdoulaye Wade, a Murid, had insisted that term limits did not apply to him. When the Senegalese took to the streets to prove him wrong, his police pelted them with tear gas and killed them. The people, in turn, set up flaming barricades, masked themselves with bandanas, hoisted signs, and otherwise enacted the rawest examples of democracy.

The pictures seemed atavistic compared to the campaign posters they competed with, but Bamba and his order have always been tied to Senegal’s modern fate. Islam has existed in what would become Senegal since the tenth century, a mere three hundred years after the death of Muhammad. Mature Sufism, however, only reached Senegal in the eighteenth century. The timing was fortuitous. The old Wolof kingdoms soon fell to European colonialism. The legalistic Islam of their court clerics fell with them. Sufi mysticism offered an alternative for renewal, and orders like Bamba’s became bastions of resistance and nascent democracy.

Today, the legalists are back. Muslim extremists, often backed by fundamentalists in the Middle East, have violently subjugated Sufis to jihad as far south as Nigeria. In September 2012, insurgents ruling parts of neighboring Mali, a coalition including al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, desecrated Sufi mosques and the tombs of saints from Gao to Timbuktu, condemning them as artifacts of profane magic. They perpetrated this destruction in addition to stoning people, beating them, or cutting off their hands. The French army has since subdued the Islamists, but in the lingering dusk of such violence, Senegalese Sufism appears once again as a faith of possibility, the potential for a popular, democratic Islam.

What remained of Amadu Bamba’s legacy after 2012’s spring of discontent? In my ignorance, I went looking for an answer from a supreme authority, Serigne Sidy Mokhtar, the current grand caliph of the Murids and Amadu Bamba’s grandson, the last indisputable seat of the saint’s soul. I hoped to find in him the same living spirit Senegalese people found in those pictures all over Dakar, where the salty sea wind blew hot and evanescent as breath.

I needed a guide. I would get two. The first was my friend and translator, Thomas Faye, a Senagalese reporter for the Associated Press whose face recalled Barack Obama’s. But Thomas is a member of the Tijaniyya, a bellicose order of Sufi wise men who famously declared armed war against the French in the first decades of their colonial rule. Thomas didn’t have a lot of intimates among Murids. He would need an assistant.

Mody Gadiaga was an improbable squire. He looked like a sea lion, not only because of his paunch or his whiskers or the odd, blubbery lump at the base of his neck, but also because of the vacancy in his dark eyes. He was a “businessman” in the way a Mafioso might use the word, a catchall term (another is “mechanic”) used by Senegalese men to give the odd or illegal jobs they work the consistent sense of occupation in a country with a 50 percent unemployment rate. But Thomas assured me Mody had connections in the brotherhood, an unlikely prospect for a guy we found sitting in a lawn chair on the street. Other than our first meeting, he never spoke directly to me. He seemed less a companion than a giant friendly specter guiding us through Dakar and the parched savanna.

I asked about the pictures of Bamba. “Of course I know the picture. I have some all over my house. From one glance, I can see his power and I get positive feelings,” Mody said. He’d seen his own visions. “I wasn’t always a Murid. I used to be a bad boy. I used to smoke cigarettes and drink beer and smoke marijuana. Then one night, twenty-two years ago, I had a dream. Saliou Mbacké, the last son of Amadu Bamba and the fifth Grand Caliph, appeared to me where I lay and said, ‘Get up.’ In the dream, I got up, and a policeman approached me and beat me. From that night on, I stopped everything.”

When he woke up, Mody sought out the one marabout, personally ordained by Saliou Mbacké. His name was Bethio Thioune. At the moment I met Mody, Thioune was in prison awaiting trial for complicity in murder. Apparently, two of his disciples had claimed Thioune was God. Thioune allegedly executed them for their blasphemy, and then had their bodies unceremoniously dumped in the bush. Thioune had always been suspiciously worldly. In addition to his fervent students, he was most famous for the frequent parties at his many homes, bacchanals of almost Roman orgiastic excess, where cows were slaughtered in herds for feasting and instant “marriages” were blessed for consummation.

“Some marabouts are not real marabouts—they don’t have baraka—but some students are easily duped,” Mody explained. I wondered how a good marabout could be in prison for conspiracy. According to Sufi thinking, it’s difficult to know how holy a person is. “A person ascends certain levels to God,” Lamane Mbaye, professor of literature at Cheikh Anta Diop University, later explained to me. “The order tries to help people reach the levels they can, but some levels are beyond different people. It’s not always easy to know what a person has or has not achieved.” In other words, the path of the soul does not always reflect the path of one’s life. A person may be more holy than they appear.

“Amadu Bamba took Sufism down from the clouds and put it in the world.”

Mody put it another way. “It is hard to tell how much baraka a marabout has. It can only be judged from miraculous things,” he said. “I have seen my marabout raise a boy from a coma in a hospital. He has prayed for me and made my business better and I threw myself into work.”

Work was Amadu Bamba’s signal ritual invention. For a long time, Sufism had insisted on the renunciation of earthly life so that a student could do nothing but learn secret prayers and mystical sciences from his teacher while seeking freedom from the body and its weakness. Bamba’s insight was that meditation was only one way to escape earthly appetites. Another was to discipline the body. To the students who could never comprehend the mysteries of the Koran or had a family to feed, labor was one more way to seek the transcendence their brethren sought in their liturgies and prayers.

“To the Murid, working is almost like praying,” was how Professor Mbaye put it. “From work, you will receive the fruit of faith.” The point was easily adapted to politics. “In a word, the development of Senegal depends upon the keystone of Mouridism: the cult and the mystique of work,” Abdoulaye Wade, a former president of Senegal, said upon his first election to office in 1998.

But before it developed any economy, the Murid cult of work did something else: it democratized Sufism. It lowered a ladder to farmers, who could practice Sufi arts by working their lands. Precocious Sufis could dedicate themselves to prayer, others could expel their breath in toil. Professor Mbaye said, “Amadu Bamba took Sufism down from the clouds and put it in the world.”

This was the world inhabited by Mody Gadiaga, “businessman” and mystic.

The brutish ruins of the Niary Tally mosque lie adjacent to the bustling thoroughfares of Dakar’s Biscuiterie district, where nothing sweet remains, only a poison cloud of petroleum fumes and the squawks of desperate textile sellers. I would not have even recognized the hollowed cavern as a mosque had I not followed Mody—loping awkwardly with his pinniped waddle—inside. The place was only twenty years old, but its concrete façade was already falling away to reveal gnarled claws of rebar grasping skyward.

At the front of the prayer niche, the imam, Serigne Cheikh Diakhaté, was concluding the afternoon prayer. He looked like what I expected a Sufi holy man to look like, wizened and crumpled, his body laid waste by lived experience, shrouded in the angelic white of a dazzling boubou, a floor-length gown. He spoke with a dignified whisper, as if his words were collapsing under the weight of the mysteries they conveyed. Mody knelt before him in supplication, greeting him in the Murid manner, knocking his forehead against the back of the imam’s palm the way he knocked his head against the floor during prayer, and told the imam why we were here.

“Well, let’s start from the beginning. To be a Murid, you have to be a Muslim. This means accepting that there is no God but Allah and that Muhammad is his Prophet. It means respecting the five pillars so you can go to paradise,” he said. “Amadu Bamba wanted his followers to do all these things. But he also wanted to add another thing: the path to experiencing God in this life. So he wrote songs and poems—khassaid—to enlighten the people.”

Bamba considered his literary output his greatest miracle: seven metric tons of manuscripts, according to legend. It had been miraculous enough that he, a black man, had learned fluent Arabic. There was no earthly accounting for his production. Bamba claimed he was visited by the Angel Gabriel. Others said each of his ten fingers transformed into quills. Still other myths claimed that the individual letters of the Arabic alphabet came to life, announced themselves to the holy man, and arranged themselves into poetry.

Like everything else in the Sufi universe, words have a hidden side separate from what they say and appear to mean. The Koran is taken to be complete—it is the ultimate revelation of God’s design—but its individual words retain a creative power left over from their aspiration in the mouths of God’s angels. This is the language of heaven, of God’s creation, and every utterance of the Arabic alphabet is a distant echo of God’s voice. Bamba took inspiration from this fact for his writing. He especially cherished one of God’s sacred names, al-Badi, “The Originator,” that face of the godhead that called into oblivion and brought forth a universe.

Many Senegalese people learn to read Arabic but don’t know what it means. So Bamba incorporated the shahada and the names of God into songs, so his followers could remember the rhythm of the words if not their meanings and so properly remember Allah. It was ingenious. Bamba’s songs, informed by the Sufi theory of language, erased the distance between word and meaning, between the divine and its inscription: God is in the words. Bamba’s Arabic, shorn of referents, unconstrained by semantic expectations, becomes the melody of pure faith.

“A saint exists to show the way,” Cheikh Diakhaté continued. “He does not supersede Muhammad, but writes odes so things can be made clear and leads people in prayer, so that they may better understand the Koran, the Prophet, and the Prophet’s life. He provides evidence to those who cannot see God.” In Bamba’s words:

“The perfection of the miracles of the Prophet / Is found in the miracles of a saint / Because they inherit that perfection from the Prophet. / And the saints are the evidence of the Lord. / The saints are the signs of the authenticity / Of His Religion and His Truth.”

The saint is an echo of God, a shadow of Muhammad, and his miracles are the evidence of things not seen.

By now, the other dignitaries at the front of the niche, the kind of men wearing expensive waxen boubous that crinkled when they moved, were leaning in, smiling mischievously, wondering what advice their imam would give this hapless initiate. “So Amadu Bamba was foremost an educator. His job was to educate people. And they followed him into the wilderness, to Touba. There, they could be together, they could write and work, and over one hundred years, it became the second biggest city in Senegal.” Bamba’s charisma literally summoned cities from the desert.

“If you want to find the saint, go to Touba, and you will find him.”

“If we’re going to Touba, you need a boubou,” Thomas said. We were waiting outside his house, in a car rented to go to the holy city of the Murids. “It is essential that you have one. I have a Baye Fall one I can give you.” The Baye Falls are a kind of mendicant sub-order of the Murids. Rather than the elegant solid colors of a rich devotee, I would be cloaked in tatters of Dutch wax print quilted together. I understood the aesthetic reflected the Baye Falls’ ethic of extreme frugality, and that it would better conceal my spiritual poverty, but, when I put it on during the drive, I still looked like the spawn of a mutant loom. “Ah! Look at that!” Thomas said. Mody pulled back his whiskers to reveal an approving smile.

We were finally on the road, a motley pack of pilgrims: me, Thomas, Mody, and a driver, also named Mody. (“There are a lot of Modys in Senegal,” Thomas explained.) We were in a car, breakfasting greedily on croissants, moving east, and our pilgrimage finally had a sense of momentum.

Touba is only one hundred miles east of Dakar, but the pulverized highway and the boundless grassland made it feel much farther. The road stretched unswervingly eastward, away from the soothing sea air of the capital and into the unforgiving glare of the savanna sun. The city announced itself from a distance. A minaret—the tallest in Sub-Saharan Africa—escaped the curvature of the earth and broke the horizon, marking the location of the Great Mosque of Touba. “There’s the mosque! That’s where you can find Amadu Bamba,” Thomas said. He meant that we would find Bamba’s mausoleum inside.

Closer to its center, Touba transforms into a Muslim amusement park relentlessly assuring believers they have indeed found the place for which they have been yearning. There are stalls hawking Korans and Koran necklaces, so you can carry the Koran around your neck at all times. There are prayer beads and pictures of saints. Dwarfing everything are the minarets of the Great Mosque, glittering like a fairy castle. The mosque is not the only material fantasy Touba has realized. The city’s exemption from civilian control once made it the epicenter of the West African black market. The many mansions of the marabouts, paid for and serviced by devout disciples, are clustered here. Somewhere among them, the Grand Caliph lived.

At the four corners of the plaza surrounding the mosque are four large, tacky metal sculptures of the basmala, Arabic proclaiming “IN THE NAME OF GOD” to everyone mesmerized by the sculptures’ ugliness. “I had a dream about those sculptures once,” Thomas said. “It was the night after Pentecost, and I dreamed one of these was actually a spaceship. There was a pilot whose face kept changing from Amadu Bamba’s to Jesus’s, and the spaceship lifted to heaven on a rainbow.” He paused as we circled one of these sculptures while Mody the Driver tried to find his way. “It was one of the most memorable dreams I’ve ever had.”

Once we parked, we began the last approach to the mosque. The entire grounds are holy and shoes are not permitted, a discouraging prospect when the sun has had a few hours to bake the flagstones. “Saliou Mbacké put down this Italian marble to protect visitors’ feet! It stays cool even in summer,” Thomas proclaimed proudly. That grace must have been lost on me; my feet were numb with pain. I told Mody the Driver it must be because of my “white-man feet,” which made him laugh, but I secretly suspected it was punishment for my pagan trespasses.

I wondered at the mansions spilling across the horizon, and asked Thomas whether we might see the grand caliph, wherever he was, somewhere out there. “No. Mody’s friend says he’s not actually here this weekend. I’m sorry.” I had hoped he was here, and that this was the reason we came out to Touba. Sometimes faith goes unrewarded.

Amadu Bamba was impatient with his humanity. He prayed to disappear into batin, the invisible world, and become nothing more or less than the breath of heaven.

We slowly ascended the steps at the rear of the mosque, where the marble disappeared into darkness. Here was Amadu Bamba, at last, lying concealed behind the walls of his hexagonal tomb.

When the French exiled Amadu Bamba to Gabon in 1895, he was still not a wali, still not a saint. The French thought they were punishing him for sedition. His followers thought his plight mimicked that of the Prophet, whose exile from Mecca was the beginning of Islam. They remembered the Koran says, “Remember when the infidels contrived to make you a prisoner or to murder or expel you, they plotted, but God planned, and God’s plan is supreme.” Bamba recalled the Angel Gabriel told Muhammad, “O! Believers! When you meet an army, stand firm and think of God profusely that you may be blessed with success.”

For Bamba, the extreme pains of exile dissolved any remaining attachments to his mortal condition. The body fell away. “It was while in exile that I was shown and cured of all my imperfections,” he wrote. “The hatred of the French has availed me all that which I desired.” Legends tell of miracles. Bamba jumped over the side of his prison ship to pray on the waters of the Atlantic, held afloat by God’s own footservants. He was imprisoned in a lion’s den where he tamed the lion. He converted infidel genies to Islam; the Angel Gabriel saved him from a stampeding bull. When he finally returned to Dakar in 1902, the Senegalese people fell down before him prostrate. The exile had lasted seven years, seven months, and seven days. Bamba and his disciples had turned the French punishment against their wardens. Bamba would be exiled again, to Mauritania, but his legend had already taken hold. The Muridiyya survived, prospered, flourished, and led Senegal to independence. Bamba was now a wali, a saint.

All of this was worth considering when I was standing in his presence in my blinding boubou. Bamba’s sainthood is indebted to some very persuasive fictions he never authored. His own writings rarely mention the events of his life, which makes sense. Amadu Bamba was impatient with his humanity. He prayed to disappear into batin, the invisible world, and become nothing more or less than the breath of heaven.

But we must live in the world of zahir, the physical and manifest. Perhaps our saints always elude us, but we chase them into heaven, clinging to whatever things they leave behind that we can feebly comprehend: relics and writings and songs and stories. And bodies. It’s ironic that Bamba desperately wanted to escape the mortal remains his followers now gravely venerate in their mosque. But there his body rests, cased in marble and surrounded by pilgrims. The room flooded with shadow even in the noonday sun, so dark it had to be lit by some suspended cylindrical lanterns. The shahada, the first prayer, looped and coursed around each circumference, declaring, “There is no god but God and Muhammad is his Prophet,” forever and ever, without end.

The compound, with its involuted corridors and manicured courtyards, betrayed itself as the home of a great eminence, even without the roiling throngs of people trying to press their way inside…. I was the focus of a hundred stares. Stupidly, I thought it might be the garish boubou I was wearing. Now I know that the boubou was the most normal thing about me.

Then revelation. On the outskirts of the mosque’s plaza, Thomas relayed another message. “Mody’s friend knows where the caliph is! But we must hurry.” We clambered into the car. “It’s in a small village and everyone is already gathering.” Mody the Driver pressed the gas, pointing north. The radio was on. Touba has its own radio station, which plays nothing but Amadu Bamba’s khaissidem sung in a throat-straining warble that echoed from the speakers.

We reached a stand of sheds and shops, wobbling on corrugated tin and arranged like an ersatz strip mall, when Mody the Driver pulled over into the wild grass. There was some frantic conversation between him and Thomas, and I thought something in the car was broken until I realized we were lost. The car lurched forward, then Mody engaged in something approximating a three-point turn, then another, until he turned off the road again, a mechanized whirl of indecision. Despite it all, Mody maintained his seal-like serenity.

A jeep pulled off the road where we were, rushing for the brush, but the collective holler from Mody the Driver and Thomas stopped them. Were they going where we were going? They were. It turned out Mody was correct the first time; the road to Sidy Mokhtar lay through the brush. We followed the jeep across the alien landscape of interior Senegal, where the dirt turned rusty-red and kicked up in long Martian streamers from the treads of our tires.

At last, we parked in a town that seemed to consist of one house, a convenience store, and a solemn gray compound. This place actually had a name: Ndindy Bougoul. The compound, with its involuted corridors and manicured courtyards, betrayed itself as the home of a great eminence, even without the roiling throngs of people trying to press their way inside. After the first door was another door to the final, inner courtyard. It turned out there were multiple entrances to this last sanctuary, arranged like answers to a riddle. Mody went to talk to one of the men guarding the entrance.

I was the focus of a hundred stares. Stupidly, I thought it might be the garish boubou I was wearing. Now I know that the boubou was the most normal thing about me. I must have looked especially ghostly, as white as Bamba’s robe, in the sun-weary eyes of the true believers.

Mody waved a hand at us, gesturing for us to go inside. He really did have connections in the brotherhood. As we approached the guard, and Mody and Thomas discussed the situation, I noticed the small earpiece hiding behind the guard’s ear. Sidy Mokhtar had a rock star’s security detail. “That guy has a cousin in Baltimore!” Thomas exclaimed. I didn’t know what that had to do with letting me into the courtyard.

As we were about to cross the threshold into the final destination, a kind of madness ensued. The waiting crowd began to push forward. Everyone had been waiting for this chance. The bottleneck at the door created an unsustainable crush, one body heaving and gasping, the men shouting, the women’s veils pulling their heads like tops. It was frightening: I felt the pressure in my chest, the disorientation from being deprived of air, and a bewildering loss of control. Then a familiar paw reached through the chaos, and Mody, grasping my wrist, pulled me inside.

Serigne Sidy Mokhtar sat impassively in a corner, his seat obscured by his saintly white gown, surrounded by an open square, full of dust. He was a carbon copy of other caliphs whose pictures I’d seen: a gray beard, a burgundy beanie, and black sunglasses. The caliph was seated unobtrusively for such a grand personage. By some kind of subtle force, the fury of the pilgrims dissipated, and the disciples sank to their knees in the dirt.

A kind of benediction commenced, as the caliph’s son, speaking for his father, called for prayer. Everyone prayed together, hands point upward toward God, and the caliph prayed over them, and that was it. The congregants stood up and filed out. Thomas tapped my shoulder. “No, this way!” We turned toward the caliph, now attended by his son and the guard with a cousin in Baltimore, and got in the dirt ourselves, crawling awkwardly on our knees to the corner.

I didn’t know what to say. I had questions, I guess, but the caliph, through his son, preempted me. He engaged me in a kind of catechism, forcing me to recite truths he may have already known.

“What is your name?”

“John.”

“And where are you from?”

“America.”

“And why are you here?”

“To learn about the legacy of Amadu Bamba.”

At this, the caliph placed his hands together so they resembled two halves of an open book. From his lungs, he summoned some words. He pronounced a prayer beyond earshot, like a secret. Then he exhaled, and it was gone.

John B. Thompson (@johnbthomp) is a writer from Columbus, Ohio. A fact-checker for GQ, he will begin a PhD in East Asian history at Columbia University in September.