Boy is not one of The Boys, but Boy is observant. At the edge of the basketball court in the park, by the locker on the far, far end of the locker room, by the punch bowl at Homecoming, by the punch bowl at Prom, nothing gets past Boy. If you cut open Boy’s head, at least fifty notebooks would fall out, each full of what Boy has written down with his eyes.

The way The Boys throw their words like sharp stones, Boy takes note. Other notes: nipples pressed against sweat-slick t-shirts during games of catch, bulges in basketball shorts and sweatpants, hands that are not his hands slipping below the waists of The Girls during slow dances.

Some of Boy’s notes are dreams. These notes are recorded on the underside of Boy’s eyelids. After tonight’s Homecoming dance, Boy dreams he has the body of a girl. Boy’s body is a song only he can hear.

Boy thinks D is going to be a beautiful dead soldier one day.

A war burns at the edge of the map Boy lives on. On clear days, Boy can see smoke rising in the distance like an old god. Boy makes note of battles the smoke reminds him of: Gettysburg, Wounded Knee, Atlanta.

The Boys have enlisted. The Boys have started wearing boots and camouflage hunting clothes to school. In the hallways, they shoot each other with guns only they can see. They die bright, fantastic deaths every chance they get.

In English, D (one of The Boys) sprays the classroom with pretend bullets. A few of The Boys die bright, fantastic deaths. D doesn’t even think to shoot Boy. With his hands below his desk where no one can see, Boy presses his palm against a pretend bullet wound in his thigh to stop the bleeding. Boy thinks D is going to be a beautiful dead soldier one day.

Boy lives in a house made of guns. At night, Boy’s father and mother sleep curled around each other like snakes. The pistols and rifles on the wall above their bed twinkle like dark stars whenever a car’s headlights pass by the room’s one window.

Boy knows this because Boy cracks open their bedroom door and takes note of how they hold each other in their sleep.

Another note: They sleep like they are rehearsing for a play about sleeping.

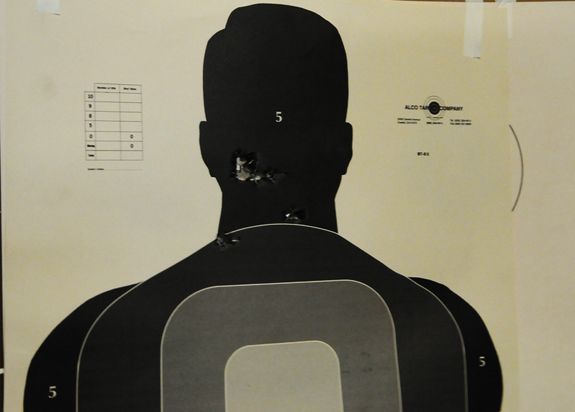

Boy’s father takes him to the shooting range every Saturday. Boy enjoys these trips as much as Boy’s father does. It is their one good thing.

Their very first visit, Boy was twelve. Boy’s father stood behind him, traced his arms along Boy’s arms, and gave advice about how to hit the black paper body a few yards ahead of them.

Boy was so busy concentrating, he wasn’t able to take any notes except for one: The black paper body shuddered, then offered up its throat.

Here, the body said.

Boy made a perfect shot. Boy’s father called over the other fathers to look at the perfect little hole in the black paper body. Boy made note of how many times his father looked at him and smiled. Three. The number of times the other fathers patted him on the back. Five.

Boy was so excited, he did a little hop. Boy couldn’t help himself. Boy noted that his father’s smile dimmed then, but only for a second.

Boy’s father has kept that black paper body hanging in the garage ever since.

Under his black hood, D moans. Boy holds onto him a moment longer—so much heat, Boy notes—then pulls out what he thinks will be a dick, hard with blood. Instead, the long end of a rifle juts out of D’s open fly.

In tonight’s dream, Boy kneels on the floor while D sits in a metal chair. A bare light bulb shines above them like a lynched moon. (Boy takes note of this.)

Boy’s heart is a grenade in his chest. Boy rakes D’s body with his eyes. D is all muscle and blood. D has on a dirty, white shirt, faded jeans, and a black hood over his head.

The light bulb turns red and Boy does what he came here to do. His hand trembles as he reaches for the fly of D’s jeans. He pulls down the zipper slowly and reaches in.

Under his black hood, D moans. Boy holds onto him a moment longer—so much heat, Boy notes—then pulls out what he thinks will be a dick, hard with blood. Instead, the long end of a rifle juts out of D’s open fly.

Boy does not stop. Boy opens his mouth, leans forward and flicks his tongue along the barrel.

In gym, Boy and The Boys sit on the floor while The Coach models how to make a free throw shot. Boy stops taking note on form long enough to look at K out of the corner of his eye. K sits with his legs wide open. K is wearing loose soccer shorts and, under them, loose plaid boxer shorts.

From where Boy is sitting, Boy can see up K’s shorts.

“Fags,” hisses K under his breath.

Scratch, scratch, goes the pen in Boy’s head. The size of K’s thigh, the scar on the left side of K’s thigh, the muscles flexing in K’s thigh, the curly hairs that begin on K’s inner thigh—

K throws out a word like a stone. Boy yanks his eyes from K’s thigh and looks up. K’s eyes are narrow as knife wounds.

“Fag,” hisses K.

All of The Boys are staring at Boy.

Sometimes Boy writes stories on the inside of his head. The story Boy writes while crying in the restroom stall is about a kingdom where, every year on the same day, boys fall from the sky like dead birds.

Boy’s English class is reading The Iliad. When Patroclus is killed, The Boys and The Girls don’t understand why Achilles goes mad with grief. The Teacher talks about male friendship.

“Fags,” hisses K under his breath.

“Fags,” hiss the rest of The Boys in agreement.

Boy is in the middle of writing a note about Achilles holding Patroclus’s cold body, when a spit ball hits his forehead. The Boys laugh. Boy doesn’t look up from his notebook. Boy’s eyes are stinging.

A second war, in addition to the first war, has started. No one calls them “wars” anymore, but no one has bothered to come up with a new name either.

Boy watches the evening news with his mother and father. The newscaster talks about the two wars without actually using the word “war,” then he moves on to a story about a man who was found dead this morning. The body was in the alleyway behind a gay bar. Baseball bats were used.

When the newscaster says that police found the word “queer” etched into the victim’s forehead, Boy’s father shifts in his seat and changes the channel. Boy’s mother asks if everyone is ready for dinner.

Notes on names Boy gets called at school: fudge packer, pansy, fairy, pillow biter, cock gobbler.

Boy reads about the myth of Ganymede. One moment, Ganymede is just a beautiful boy standing on a hillside. The next, Zeus descends upon him in the form of an eagle and takes the boy to live among the gods.

The book uses the word “abducts.”

Boy wonders who wouldn’t want to be abducted.

Boy makes an online profile. He says he is 19 even though he is 16. Boy logs into the chat room and clicks on the profiles of other users. Boy makes note of different ways to say hello.

Boy: Hi there.

CollegeBoy78: Sorry, not into black guys.

Boy: Hey. What’s up?

TNJock24: Not my type.

Boy: What’s up?

Hot4Mouth: [this user has blocked your profile]

Boy does an experiment. He finds the picture of a white boy with a similar height and build and uses it to create a new profile. Boy finds the profiles of the same users he tried chatting with before.

Boy: Hey.

CollegeBoy78: Hi. What are you into?

Boy: What’s up?

TNJock24: Not much. Nice picture. What are you into?

Boy: Hi there.

Hot4Mouth: Hey, sexy.

Boy notes that his father’s eyes are as narrow as knife wounds now, just like the eyes of The Boys.

One afternoon, Boy gets home from school and goes to his bedroom to jack off. When Boy opens his bedroom door, he sees the gay porn magazine he has kept hidden under the mattress laying open on the bed. Boy’s father sits beside the magazine.

Boy notes that his father’s eyes are as narrow as knife wounds now, just like the eyes of The Boys.

Boy turns into a deer caught in headlights, a deer that cannot move, a deer that could kill everyone in the approaching sedan by simply not moving. Boy’s father holds his gaze like a driver who refuses to swerve.

All of the sentences in Boy’s mouth come out broken.

“It isn’t—” Boy says.

“I—” Boy says.

“I swear I—” Boy says.

Boy’s father rolls up the magazine into a baton and stands.

Boy opens his mouth to say “father.”

The fist of Boy’s father comes down like war itself.

When Boy comes to, he’s on the floor. A pistol rests on the bed where the magazine had been.

In line in the cafeteria, at his favorite table in the library, on the last block before the block he lives on, the inside of Boy’s head is one blank notebook page after another.

Hades is not hell, Boy thinks again, this time with a man inside his mouth.

One night, while Boy’s parents are asleep, Boy steals his father’s car. The entire drive, Boy prays the car doesn’t break down. Boy doesn’t know how he would explain his dad’s car breaking down in the gay part of town.

This is Boy’s second trip to Throckmorton Mining Company. It’s not a mining company, of course, but a gay dance club. Inside, it looks like an abandoned shaft lit with fake candles. A dead canary lies in the cage by the entrance.

The canary is not real is Boy’s first note in weeks.

Boy feels eyes on him the moment he steps into the black light. Boy has on a white shirt. He likes what black light does to his black skin. Boy feels the eyes on his body turn into the hands on his body and the hands on his body turn into bodies against his body.

Boy hardly talks all night. There is a tornado inside Boy’s silence.

Hades is not hell, Boy notes.

The Stranger is old enough to be Boy’s father, but he has the body of a soldier. The Stranger’s shirt is unbuttoned to show off his six-pack. Boy feels The Stranger up against him before he sees him. When they dance, Boy looks up into The Stranger’s face for a moment. The Stranger has an easy smile. Boy makes a note: Learn how to smile like that.

When one song bleeds into another, The Stranger takes Boy’s hand and leads him into a one-stall restroom.

Hades is not hell, Boy thinks again, this time with a man inside his mouth.

All of the lights are on in the house made of guns when Boy eases his father’s car back into the driveway. Boy does not rush. Boy makes note of the number of steps from the garage to the living room. Fifteen.

Boy walks into the living room and walks right up to Boy’s father. Boy wonders if his father can hear the tornado ripping up the notebooks in his head.

Boy looks for his mother for a second, only sees the bottom of her feet at the top of the steps, then holds out the car keys as if to drop them in his father’s hand.

Boy’s smile looks like it has been cut into his face.

Boy’s father’s fist comes down like a war no one bothers to call a war.

In the Biology lab, in the bedroom he is not allowed to leave in the evenings, at the dinner table encased in silence, scratch, scratch, scratch, go the furious pens inside Boy’s head. Scratch, scratch, scratch.

A third war starts and it doesn’t even make the news. The same night that war begins, Boy walks down the hallway, cracks open his parent’s bedroom door and steps inside. He has been holding the pistol for so long, it is warm in his hand.

Boy stands just like Boy’s father has taught him. Boy raises the pistol and takes aim.

Seconds are years in the almost dark. Scratch, scratch. The dull heat of the gun. The vague smile on Boy’s sleeping mother’s face. The way Boy’s father murmurs for a second then snores.

Boy stands beside their bed until his legs begin to ache. Boy brings his the pistol down for a moment.

Boy has a name. Boy whispers his name once in the almost dark, smiles briefly then takes a step back.

Saeed Jones received his MFA in Creative Writing at Rutgers University—Newark. His poems and essays have appeared in Ebony, The Rumpus, Lambda Literary, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Jubilat and Blackbird. He has received fellowships from Cave Canem and Queer/Arts/Mentors. His chapbook When the Only Light is Fire is available from Sibling Rivalry Press. His blog is For Southern Boys Who Consider Poetry.