Roberto Bolaño is being sold in the U.S. as the next Gabriel García Márquez, a darker, wilder, decidedly un-magical paragon of Latin American literature. But his former friend and fellow novelist, Horacio Castellanos Moya, isn’t buying it.

I had told myself I wasn’t going to say or write anything more about Roberto Bolaño. The subject has been squeezed dry these last two years, above all in the North American press, and I told myself that there was already enough drunkenness. But here I am writing about him again, like a vicious old man, like the alcoholic who promises that this will be the last drink of his life and who, the next morning, swears that he will only have one more to cure his hangover. The blame for my relapse goes to my friend Sarah Pollack, who sent me her insightful academic essay on the construction of the “Bolaño myth” in the United States. Sarah is a professor at The City University New York and her text “Latin America Translated (Again): Roberto Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives in the United States” was published in the summer issue of the journal Comparative Literature.

I had told myself I wasn’t going to say or write anything more about Roberto Bolaño. The subject has been squeezed dry these last two years, above all in the North American press, and I told myself that there was already enough drunkenness. But here I am writing about him again, like a vicious old man, like the alcoholic who promises that this will be the last drink of his life and who, the next morning, swears that he will only have one more to cure his hangover. The blame for my relapse goes to my friend Sarah Pollack, who sent me her insightful academic essay on the construction of the “Bolaño myth” in the United States. Sarah is a professor at The City University New York and her text “Latin America Translated (Again): Roberto Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives in the United States” was published in the summer issue of the journal Comparative Literature.

Albert Fianelli, an Italian fellow journalist, parodies a quote often attributed to Herman Goering and says that every time someone mentions the word “market,” he reaches for his revolver. I’m not so extreme, but neither do I believe the story that the market is some kind of deity that moves on its own according to mysterious laws. The market has its landlords, like everything on this infected planet, and it’s the landlords of the market who decide the mambo that you dance, whether it’s selling cheap condoms or Latin American novels in the U.S. I say this because the central idea of Pollack’s work is that behind the construction of the Bolaño myth was not only a publisher’s marketing operation but also a redefinition of the image of Latin American culture and literature that the U.S. cultural establishment is now selling to the public.

I don’t know if it’s my bad luck or if it happens to my colleagues as well, but every time that I’ve found myself on American soil—at the airport bar, at a social gathering, wherever—and I’ve made the mistake of admitting to a citizen of that country that I’m a fiction writer who comes from Latin America, that person will immediately pull out García Márquez, and will do it, what’s more, with a self-satisfied smile, as if he were saying to me, “I know you, I know where you come from.” (Of course, I’ve found myself with wilder ones who boast about Isabel Allende or Paolo Coelho, which, ultimately, makes no difference at all, since Allende and Coelho are little more than the light and self-help versions of García Márquez.) As time goes by, however, those same North Americans, at those same bars and social gatherings, have begun to pull out Bolaño.

The key idea is that for thirty years, the work of García Márquez, with its magical realism, represented Latin American literature in the imagination of the North American reader. But since everything tarnishes and ends up losing its luster, the cultural establishment eventually went looking for something new. It sounded out the guys in the literary groups called McOndo and Crack, but they didn’t fit the enterprise—above all, as Sarah Pollack explains, it was very difficult to sell the North American reader on the world of iPods and Nazi spy novels as the new image of Latin America and its literature. Then Bolaño appeared with his The Savage Detectives and his visceral realism.

“Nobody knows for whom they work” is a phrase that I like to repeat, but it’s also a coarse reality that has struck me again and again in life. And not only me, I’m sure of that. Let’s continue. The stories and the brief novels of Bolaño were being published in the United States very carefully and tenaciously by New Directions, a very prestigious independent publisher with a modest distribution, when all of a sudden, in the middle of negotiations for The Savage Detectives, appeared, like a bolt from the blue, the powerful hand of the landlords of fortune, who decided that this excellent novel was the work chosen to be the next big thing, the new One Hundred Years of Solitude, if you will. And it was written, what’s more, by an author who had died a little earlier, which facilitated the process of organizing the operation. The construction of the myth preceded the great launch of the work. I quote Sarah Pollack:

- “Bolaño’s creative genius, compelling biography, personal experience of the Pinochet coup, the labeling of some of his works as Southern Cone dictatorship novels, and his untimely death from liver failure on July 15, 2003, at the age of fifty contribute to ‘produce’ the figure of the author for U.S. reception and consumption, and in doing so, anticipate the reading of his work that is propagated in this country.”

The market has its landlords, like everything on this infected planet, and it’s the landlords of the market who decide the mambo that you dance, whether it’s selling cheap condoms or Latin American novels in the U.S.

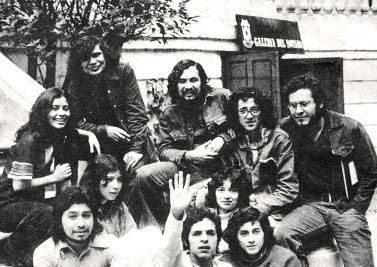

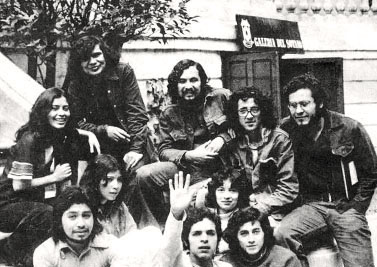

Maybe I was not the only one surprised when, on opening the North American edition of The Savage Detectives, I found a photograph of the author that I didn’t recognize. It is a post-adolescent Bolaño, with his long hair and mustache, the look of a hippie or of the young non-conformist in the time of the infrarealists—the poetry movement he helped found in Mexico in 1974—and not the Bolaño who wrote the books that we know. I was delighted at the photo, and since I’m naïve, I told myself that surely it had been a stroke of luck for the editors to get a photo of the time to which the greater part of the novel alludes. (Now that the infrarealists have started their own website, you can find several of these photos posted there, among which I recognize my pals Pepe Peguero, Pita, “Mac,” and even the Peruvian journalist José Rosas, now settled in Paris, whose connection to the group I wasn’t aware of.) It didn’t occur to me to think then, since the book had just come off the press and was beginning to cause a stir in New York, that this nostalgic evocation of the rebel counterculture of the sixties and seventies was part of a finely-tuned strategy.

It was no casual fact, then, that the majority of articles profiling the author laid the emphasis on the episodes of his tumultuous youth: his decision to drop out of high school and become a poet; his terrestrial odyssey from Mexico to Chile, where he was jailed during the coup d’état; the formation of the failed infrarealist movement with the poet Mario Santiago; his itinerant existence in Europe; his eventual jobs as camp watchman and dishwasher; a presumed drug addiction; and his premature death. “These iconoclastic episodes coupled with Bolaño’s death at fifty,” writes Pollack, “are too tempting to narrate as anything but a tragedy of mythical proportions: here seems to be someone who actually saw his youthful ideals through to their ultimate consequences.” “Meet the Kurt Cobain of Latin American literature,” wrote Daniel Crimmins in Paste magazine.

Every time I’ve found myself on American soil and I’ve made the mistake of admitting that I’m a fiction writer who comes from Latin America, that person will immediately pull out García Márquez, and will do it, what’s more, with a self-satisfied smile, as if he were saying to me, “I know you.” Now, those same North Americans have begun to pull out Bolaño.

No North American journalist highlighted the fact, Sarah Pollack warns, that The Savage Detectives and the greater part of Bolaño’s prose work “were written as a sober family man” during the last ten years of his life—and an excellent father, I’d add, whose major preoccupation was his children, and that if he took a lover at the end of his life, he did it in the most conservative Latin American style, without threatening the preservation of his family. Pollack notes that “Bolaño appears to the reader, even before one crosses the novel’s threshold, as a cross between the Beats and Arthur Rimbaud (another reference for his alter ego Arturo Belano), his life already the stuff of legend.” Yet the majority of critics have passed over the fact that Bolaño didn’t die as a result of drug or alcohol abuse, but from a case of poorly cared-for pancreatitis that had destroyed his liver; or that his case was more similar to those of Balzac or Proust, who also died at fifty after a tremendous work effort, than it was to those of North American pop idols.

I can tell you, though, that Bolaño would have found it amusing to know they would call him the James Dean, the Jim Morrison, or the Jack Kerouac of Latin American literature. Wasn’t the first novella that he wrote a quatre mains with García Porta called Advice from a Morrison Disciple to a Joyce Fanatic? Maybe he wouldn’t have found so amusing the hidden reasons that they called him that, but that’s flour for another sack. What is certain is that Bolaño was always a non-conformist; he was never a subversive or a revolutionary wrapped up in political movements, nor was he even a writer maudit. He was a non-conformist, just as the Royal Spanish Academy defines it: “One who polemicizes, opposes, or protests[…] anything established.”

From the beginning of the nineteen seventies, he was non-conformist against the Mexican literary establishment—already represented by Juan Bañuelos and Octavio Paz. With that same non-conformist mentality, and not with any political militancy, he went to Allende’s Chile. (Speaking of this trip, about which a journalist from the New York Times has cast some doubt, I called my friend the filmmaker Manuel “Meme” Sorto in Bayonne, France, where he lives now, to ask him if he was not certain that Bolaño had spent the night at his house in San Salvador when he went through Chile and also on his return—Bolaño mentions it in Amulet—and this is what Meme told me: “Roberto came still shaken up by the fright he’d had in jail. He stayed in my house in the Atlacatl colony and then he rode to the Parque Libertad stop and took the bus to Guatamala.”) And he remained a non-conformist up to the end of his life, when fortune had already begun to touch him: he attacked the sacred cows of Latin American literature, especially the boom, which he called, in an email he sent me in 2002: “the rancid private club full of cobwebs presided over by Vargas Llosa, García Márquez, Fuentes, and other pterodactyls.”

The majority of critics have passed over the fact that Bolaño didn’t die as a result of drug or alcohol abuse, but from a case of poorly cared-for pancreatitis that had destroyed his liver; or that his case was more similar to that of Balzac or Proust, who also died at fifty after a tremendous work effort, than it was to that of North American pop idols.

It was this non-conformity that served to perfection the myth’s construction in the United States, in the same way that this aspect of Che’s life (the motorcycle journey and not the experience as minister of Castro’s regime or guerilla leader assassinated by the CIA) is what was used to sell his myth in the same market. The new image of the Latin American is not so new, then. But the old mythology of the road trip, which came from Kerouac, has now been recycled with the face of Gael García Bernal (who will also portray Bolaño in an upcoming film, by the way). The novelty for the American reader is that he will come away with two complementary messages that appeal to his sensibility and expectations: on one side the novel evokes the “youthful idealism” that leads to rebellion and adventure. But on the other side, it can be read as a morality tale, in the sense that “it is very good to be a brazen rebel at sixteen years old, but if a person doesn’t grow and change into an adult person, serious and established, the consequences can be tragic and pathetic,” as in the case of Arturo Belano and Ulises Lima. Sarah Pollack concludes: “It is as if Bolaño were confirming what U.S. cultural norms tout as truth.” And I say: so it was in the case of our distinguished author, who needed to sit down and count on a solid family base to write the work that he wrote.

What isn’t the fault of the author is that American readers, with The Savage Detectives, want to confirm their worst paternalistic prejudices about Latin America, as Pollack’s text says, like the superiority of the Protestant work ethic or the dichotomy according to which North Americans see themselves as workers, mature, responsible, and honest, while they see their neighbors to the South as lazy, adolescent, reckless, and delinquent. Pollack says that from this point of view The Savage Detectives is “a very comfortable choice for U.S. readers, offering both the pleasures of the savage and the superiority of the civilized.” And I repeat: nobody knows for whom it works. Or as the poet Roque Dalton wrote: “Anyone can make the books of the young Marx into a light eggplant puree. What is difficult is to conserve them as they are, that is to say, as an alarming ants’ nest.”

(A version of this essay originally appeared in Spanish in the Argentine newspaper, La Nación. Translated by Robert P. Baird and Wes Enzinna.)

Born in Honduras in 1957, Horacio Castellanos Moya is the author of nine novels, among them El Asco: Thomas Bernhard en San Salvador, about which Roberto Bolaño once wrote, this novel “threatens the hormonal balance of imbeciles, and those who read it feel the irrepressible desire to hang the author in a public plaza. In truth, there is no higher honor for an author.” His novels available in English include Senselessness (New Directions), The She-Devil in the Mirror

(New Directions), and Dance with Snakes (Biblioasis). He lives in exile in Tokyo, Japan, and was interviewed in _Guernica_’s “April 2009 issue.