2013 HD video, sound, 5 minutes

“Pastoral scene / Of the gallant South / Them big bulging eyes / And the twisted mouth…”

—Nina Simone, “Strange Fruit”

“I see the blood on the leaves. I see the blood on the leaves. I see the blood on the leaves.”

—Kanye West/Yeezus, “New Slaves”

Upon entering M. Lamar’s first solo show, NEGROGOTHIC: A Manifesto, The Aesthetics of M. Lamar, at Participant Inc. Gallery on Manhattan’s Houston Street, viewers will encounter a wooden pillory with three dog-eared books stacked on top: Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, and The Cornel West Reader. The title of the piece is “Surveillance Punishment and the Black Psyche I.”

2013 HD video, sound, 5 minutes

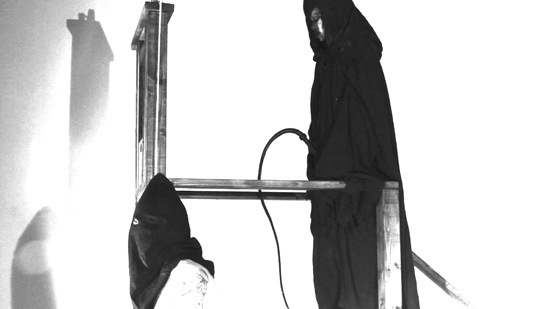

Beyond a series of stills on canvas taken from two videos at the front of the room is “Surveillance Punishment and the Black Psyche, Part Two, Overseer,” in which a tall, long-haired figure dressed in black presides over an audience of nude white men, their asses raised in supplication; a shirtless white man, wearing skinny black jeans and a bullet belt, wields a whip, cracking it toward the cloaked figure, an androgynous black man holding a bucket of picked cotton. The shirtless punk descends the scaffold toward the figure in black, and the two kiss near the cotton trees, as a classically trained falsetto voice is layered over the romantic horror scene. The audience, tipping toward white and male, lingers over the still images, but it’s difficult to tell how much is sinking in.

Reginald M. Lamar goes by M. Lamar professionally. Aside from his music, he is perhaps best known as the twin of Laverne Cox, the transgender character Sophia in Orange Is the New Black and Time magazine cover star. Lamar and Cox were born and raised in Mobile, Alabama. After moving to San Francisco for college, Lamar received his BFA from the San Francisco Art Institute, then went to Yale for his MFA, but left after a year. “I basically dropped out and started a rock band,” he says, laughing. “I was still doing my work. One of the first songs I wrote for my band was called ‘Plantation Mistress.’”

During our conversation in an East Village café, Lamar uses bell hooks’s line “white supremacist capitalist patriarchy” as if it were one word. His hands are alive, moving in fluid motions around him as he presents his ideas in ten-minute rapid-fire monologues. He’s wearing an all-black outfit, with fingerless, studded black leather gloves, and a large silver skull ring. At one point, he takes off the gloves, as if to make his hands lighter. They are birds in flight. He knows how to talk the talk of art and academia, and his references are formidable. He invokes everyone from Cindy Sherman to Judith Butler.

“What’s really in the foreground of images in the show is whiteness; white people looking at black people.”

In her essay “Restorative Power of Sound: A Case for Communal Catharsis in Toni Morrison’s Beloved,” Roxanne Reed writes: “Sound becomes the vehicle for communal restoration and the means by which the women in the novel demonstrate spiritual authority…” In his music and artwork, Lamar provokes and probes his audience, holding us accountable for the sins of the past that pervade the present. His videos are haunting things, conjuring numerous influences, from The Passion of Joan of Arc to the vocal stylings of Antony Hegarty and Diamanda Galás, the camp and bravado of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, and the presence of his hero(ine), the black soprano Leontyne Price.

Each white actor in the credits is listed as “witness/overseer,” acknowledging the power dynamic implicit in the white male gaze. “What’s really in the foreground of images in the show is whiteness; white people looking at black people,” Lamar says. “I’m not interested in white people’s imaginings of black people, but since it’s obviously not going to stop anytime soon, then I think there’s an amount of urgency for white people to start looking at things differently, to really interrogate their personality in terms of these long kinds of histories and these long narratives, which white people seem unwilling to do.”

For Lamar, the videos he makes also function as radical acts of self-acceptance, confronting a fear of black male sexuality and the mere existence in general of black men in the US, whether in historical narratives, popular movies, or in pornography. The basis for “Surveillance Punishment and the Black Psyche, Part Two, Overseer,” is the story of Willie Francis, a sixteen-year-old who was executed in Louisiana in 1947 for allegedly killing his white boss. But what if they were lovers? Lamar’s re-examination of the historical record opens up new possibilities. And although his message is, at this point in history, radical, Lamar’s disciplined approach to musical training and use of sound is undeniably conservative. He’s a classically trained musician who studies opera and uses his voice as a well-crafted conduit for his ideas, spending hours taping and re-taping his songs. “I’m interested in voices that take you from one place to another place,” he says. “I just don’t think you can do that untrained… The voice needs to be able to soar.” Songs of subjugation are melded with a horror-punk aesthetic, resulting in traditional, repetitive song structures that are meant to unsettle the listener, who is a witness to a self that exists in the past, present, and future simultaneously. With this, Lamar is especially effective; his songs stay with you long after you’re done listening.

Near the end of our meeting, Lamar starts talking about personal, rather than collective, trauma. He says about his sister, “Growing up, she was always dancing. Looking back, she was very free, much more so than I was, actually… But I saw the repercussions of her freedom, so I was more guarded.” He never really felt love from his distant mother, and growing up, this resulted in self-hate, erasure, abnegation. In fact, he is preparing for this current work to be dismissed, but in its questioning of our foundations, its examination of how we got here and how to let go, it has an incredible resonance. “I want to leave something behind,” he says. “I want to open some doors for someone else, who is more brilliant than I am. I know I’m speaking to a small audience. But who knows?”

NEGROGOTHIC: A Manifesto, The Aesthetics of M. Lamar runs through October 12.

Kathleen Massara is a senior editor at Christies.com and the former arts & culture editor of The Huffington Post.