Iraqi-born, Finland-based sculptor and media artist Adel Abidin is not afraid of controversy. His work often begins by criticizing outdated social conventions or cultural taboos.

The work shown as “Symphony” was created in reaction to violent incidents in Iraq last year when dozens of teenage boys were pummelled to death with concrete blocks by religious extremists for their “emo” appearance. The installation includes a video and a morgue, where sculpted teenage bodies are kept unpainted, and details are sparse. The video places the bodies into a larger field, portraying a scene in the wake of slaughter. Each body is tied to an animated dove, a motionless corpse on the ground contrasted by flailing wings. The beating of the birds’ wings is presented as a sound composition.

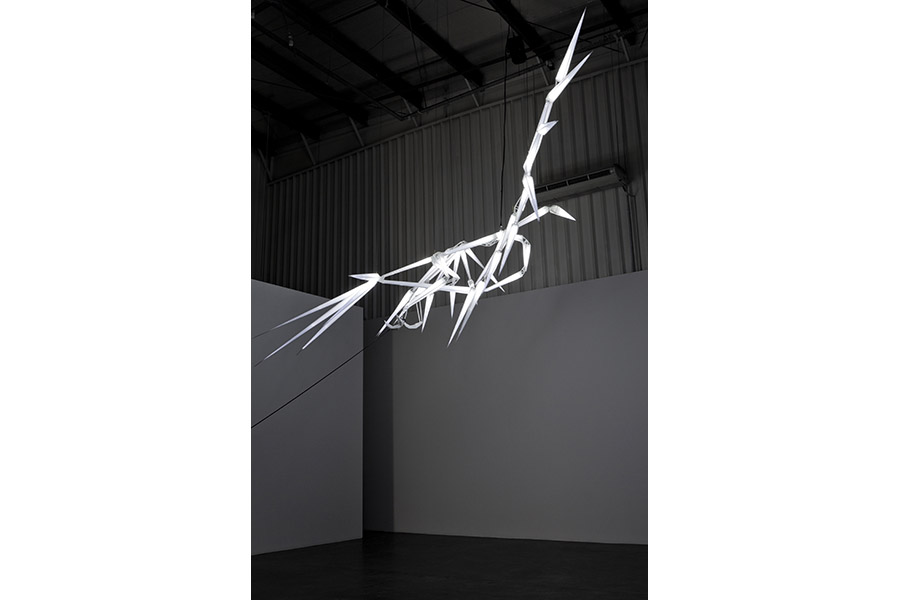

Abidin constructed the bird skeleton, “Al-Warqaa,” made separately from “Symphony,” by using the dove frames from the video installation. “Al-Warqaa” takes an analogy from the pre-modern Islamic philospher Ibn Sina’s poem, conveying thoughts about the soul’s journey through a dove’s flight.

—Haniya Rae for Guernica

Guernica: In 2012, the murders of young “emo-looking” boys in Iraq became a catalyst for this series of work. It obviously affected you deeply. Did you know any of the young boys in the attacks?

Adel Abidin: Actually, I heard the story from a Finnish guy. I was sitting in a bar in Finland, and I didn’t check the news that day. I thought he was joking. I started researching what had happened. It seemed like a turn in the way people were discriminated against; it wasn’t religion or ethnicity, but targeting people and killing them because of their hairstyle or what they were wearing. These kids were starting their own lives and had their own ideas. I thought they were heroes, and so I should make something for them, show respect for them after such a brutal act. I progressed with this idea until I came up with a visual.

Guernica: What to you constitutes “emo”?

Adel Abidin: According to what I read about this case, many of the kids were killed because extremely religious groups thought they were gay. There was also a thread of thought that these kids were Satan worshippers. When you are fundamentalist in what you do, you become narrow-minded, thinking of things in black and white. There are online letters written in Arabic telling other students to avoid such associations, otherwise they will be in danger.

These kids took visuals from what they considered “emo” culture in the U.S., wearing tight black clothes. They were following the movement that started in the ’80s in D.C., that was supposed to be against violence. I’m not sure the Iraqi kids knew the deeper part of the movement, but they thought it was cool and wanted to emulate it. When I was a teenager in Baghdad, my friends and I thought we were in the “Grease” movement. But the logo on our jackets said “E.T.”—from “E.T. go home.” It didn’t mean anything. Officials have kept quiet because they want it to appear as if it never happened. And the families of the boys don’t want to talk about it because they don’t want to be shamed.

Guernica: Growing up in Iraq, were you religious?

Adel Abidin: My family wasn’t a religious family. They believe in Islam, but they weren’t strict—I could believe what I wanted to. I read The Bible and The Koran, and came to the conclusion that I didn’t believe in the institution of religion. It’s not a physical thing for me, it’s completely a spiritual thing.

Guernica: How is “Symphony” connected to “Al-Warqaa”?

Adel Abidin: The shape of the bird—it’s the wire frame from the animation of doves in the video. These aren’t actual doves, but 3D renderings. The skeleton looks like a dinosaur. When I was doing the animation, I was interested in capturing these souls. When the work was first shown in Istanbul, it was just the video and the statues in the morgue. I thought it’d be nice to have a departure, and added the bird and the mask, which is a large TV expressing the commotion and movements of the doves.

Guernica: The morgue scene comes across as very literal.

Adel Abidin: The work balances the concept with reality. In considering a physical space for the bodies, I thought putting the boys on a pedestal would look pretentious. So I sculpted them before they burn, in the autopsy room. It’s the stage before the final discrimination, after death. The stage where they sleep among people and leave as a physical body, not as a soul.

Guernica: Would you put your work in front of Iraqi officials, or the parents of the boys that were lost?

Adel Abidin: The piece is inspired by specific events, but it’s apart of a bigger phenomenon phenomenon of discrimination against “emos,” and has occurred in Mexico as well. I hope that many people see and feel the piece.

To contact Guernica or Adel Abidin, please write here.

Adel Abidin (1973, Baghdad, Iraq) received a bachelor’s degree in Painting from the Academy of Fine Arts in Baghdad in 2000 and a master’s degree in Media and New Media Art from the Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki in 2005, focusing on installation, interactive installations, videos, and photography. Abidin has exhibited in numerous group and solo exhibitions such as The Helsinki KIASMA Museum of Contemporary Art, The DA2 Domus Atrium 2002 Centre of Contemporary Art (Salamanca), The Mori Art Museum (Tokyo), Mathaf Museum (Doha), Location One Gallery (New York), the 17th Sydney Biennale, Aksanat (İstanbul), the 10th Sharjah Biennale, and the 52nd Venice Biennale where he represented Finland with “Abidin Travels,” a mock travel agency that promotes tourist trips to Baghdad. In 2011, he presented new work in a string of solo exhibitions at Darat al-Funun (Amman), Gallerie Anne de Villepoix (Paris), and Wharf: Centre d’Art Contemporain de Basse (Normandy). He also exhibited his critically acclaimed video installation, “Consumption of War,” at the Iraqi Pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale. Adel Abidin works and lives in Helsinki.

Adel Abidin’s “Symphony” was a solo exhibition held at Lawrie Shabibi gallery in Dubai from March 18th to April 22nd, 2013. All photos courtesy the gallery.