By Ben Mason

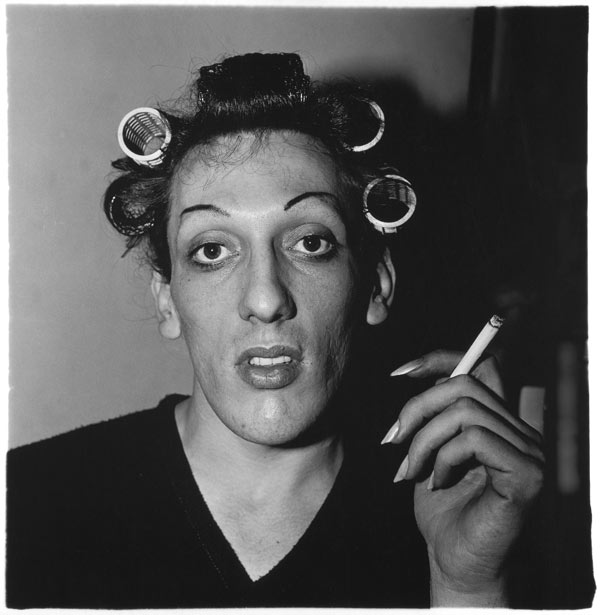

A pair of protuberant eyes looks out at you. Past the carefully-applied mascara, they look tired below high, plucked eyebrows. One side of the young man’s face is half in shadow, and your attention jumps around the curiosities on show: the rollers in his hair, a lit cigarette held between fingers not quite slender enough for the manicured nails to look entirely natural; but always the gaze is drawn irresistibly back to those eyes. The man’s expression is inscrutable: direct, perhaps even challenging, and yet slightly vacant too, his glossed lips slightly parted above a thick-set chin with a shadow of stubble. The effect of the photograph is, above all, unsettling. It draws in your attention but then holds it captive without letting it comfortably rest.

In fact you meet A young man in curlers at home on West 20th Street before setting foot in the museum. The image looms in large posters advertising the exhibition as you round the corner of Niederkirchnerstrasse. The remaining walk is accompanied on one side by around 200 meters of bare concrete and rusty steel wire: the longest surviving stretch of the Berlin Wall.

Arbus sought permission to photograph in prisons, nudist camps, psychiatric hospitals, institutions for the mentally retarded; she said: “I really believe there are things which nobody would see unless I photographed them.”

This is a short walk from Potsdamer Platz, one of Berlin’s most peculiar quarters. Once a busy commercial centre, it was largely destroyed by Allied bombing, then bisected until 1989. Since then it has been a centerpiece for the enormously expensive regeneration of the capital. The results, as is true of the whole city, are rather mixed: skyscrapers bearing corporate logos rear imposingly. The atmosphere on the ground, despite a handful of restaurants, is sterile and uninviting, with few pedestrians on the streets. Walk for a minute and the surrounding streets become deserted, save for the occasional prostitute. Despite being the geographical heart of the city, Potsdamer Platz feels remote and rather desolate.

Once you enter the Martin-Gropius-Bau, (the name suggests daring modernity which a facade of grubby columns does not deliver), the same arresting quality strikes in picture after picture. Diane Arbus’s photography shows a fascination with the outsider, living out an extraordinary existence barely noticed on the fringes of society. Cross-dressing men are a recurring theme, as are circus sideshow acts: her portraits introduce us to dwarves, giants and Walter L. Gregory – “The Mad Man from Massachusetts.” Tattooed arms hugged tight around his chest, his body, abnormally thick neck and single eye are lit brightly against a black background. As with many of the photos, you experience an involuntary revulsion, leaving you feeling guilty, almost exploitative. Arbus sought permission to photograph in prisons, nudist camps, psychiatric hospitals, institutions for the mentally retarded; she said: “I really believe there are things which nobody would see unless I photographed them.” The effect of such unusual characters and bizarre scenes—such otherness—is powerful.

The images insistently make us confront, inspect, interact with those who have crossed a line, who are, by choice or not, other.

Critics have been divided about the source of this power in photography. Susan Sontag reviles it as a cheap thrill, like watching a freak-show, staring from a safe and privileged distance. Certainly there is a kind of voyeurism here, intensified by the intimacy of many of the portraits, by the nudity and the deformities. But this alone cannot explain the disturbing sensation the viewer feels in one picture after another—it is not as simple as peeking furtively over a boundary at that which is inherently and irrevocably removed from us. They unsettle us so deeply because we see a little bit of ourselves looking back at us in these forgotten people.

There is a forced engagement: the images insistently make us confront, inspect, interact with those who have crossed a line, who are, by choice or not, other—and in the end it is this line which is questioned and blurred.

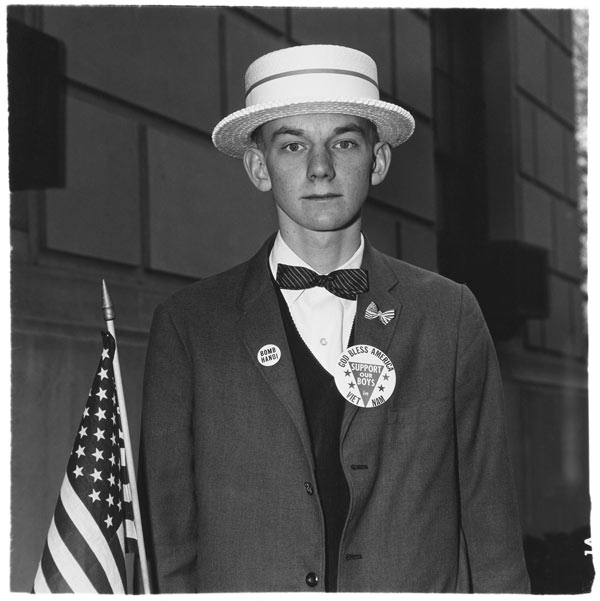

The playing out of this tension is nowhere so clear as in one of Arbus’s best-known works. To modern eyes a faintly comic straw hat sits low on the brow of an adolescent boy. He is saved from blending into the wall behind him by the white of his shirt and his lapel badges, one of which says “BOMB HANOI” in small, plain letters. We experience a jolt at the words, but the openness, the obvious vulnerability in his young features, with his earnest eyes and outsize ears, make it a challenge to see him as totally isolated from ourselves, as utterly beyond our reach.

It is striking how the photographs connect with their new setting of Berlin. They now hang a few meters from the former site of the Wall, the boldest attempt in history at creating and imposing an artificial otherness, alienation by stipulation and barbed wire. This is a city that has been wrenched apart, and which is still reconciling itself to being unified again. Just as our position in history affects our reaction to the young pro-war demonstrator, now these pictures can’t help but speak to the experiences of Berlin and the mark it has left in the minds of its inhabitants.

The photographs now hang a few meters from the former site of the Wall, the boldest attempt in history at creating and imposing an artificial otherness, alienation by stipulation and barbed wire.

In a letter to a friend, Arbus describes biblical original sin as “sundering everything which was once one into a pair of opposites . . . all the endless pairs of things, irreconcilable and inseparable.” The letter appears alongside old cameras and notebooks in the documentary section at the end of the exhibition, where her fascination with ideas of separation and unity are made explicit. Elsewhere a book of Plato’s dialogues stand open to show that she underlined the sentence: “A thing is not seen because it is visible, but conversely, visible because it is seen.”

So what significance can we find in the pictures’ temporary home: a building of washed-out grandeur which once peered over the Iron Curtain? Different people will come to their own interpretations, but the images’ way of bringing to the fore what is invisible or shunned, and then questioning its outsider status, resonates clearly. It would be going too far to say the exhibition’s message is unambiguously unifying and redemptive; rather it lays bare the impulse of people everywhere to divide and push away, when often more unites us than we would admit.

The photographs of this exhibition capture the essence of a time and place—Arbus took almost all these pictures in New York City during the 1960s and ’70s. What is remarkable is how these pictures, and the themes of exclusion and unity they explore, can speak so plainly across a century and a continent. These drag queens, teenagers, freaks, all firmly rooted in their time, engage us now more forcefully than ever. As Arbus said: “the more specific you are, the more general it will be.”

The Diane Arbus exhibition runs at the Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin through September 23, 2012.

Ben Mason is a freelance writer and journalist based in London. He has written for The Times in the Arts, Books and Opinion pages, and is the winner of the London Library Student Prize 2012