Growing up, Beirut seemed to have a five-block radius—school; my dad’s dairy store; greengrocers; the houses of friends. My area of Ain el-Rammaneh—a working-class neighborhood—was home. It smelled like oranges. It was also on the frontline of the civil war that started in the 1975, one month and thirteen days after I was born, and officially ended in 1990. The capital Beirut was ground zero—split into East and West by the green line, where wild plants grew due to the absence of people. Ain el-Rammaneh was in the East. My dad would listen to the radio constantly, even as he slept. To wake him up, we would turn the machine off. It’s possible that his radio, along with his anxiety, is why we’re alive today.

We left that home several times.

My family spent two years up north in our village at my grandparents’ house to escape the fighting. Mazraat el Toufah (The Apple Orchard) is where I made my first memories. It’s also the place where I accidentally broke the radio’s flimsy battery cover and cried inconsolably because I falsely assumed this would cost me my dad’s love.

Years later, we sought refuge again, for several months, at my aunt’s home in the suburb of Naccache. It was my eighth birthday, and I demanded a celebration. Money was tight and driving was risky, so my mom found a bag of pistachios in my aunt’s fridge and used them to decorate a homemade cake. I threw a fit and sat under the table. I hated green and pistachios. My brother joined me and shared words of wisdom: “Why do you care what the cake looks like? Don’t you know what happens to cake after you eat it? It becomes khara (shit). In the end all cakes become khara.” I got up with renewed excitement. It was a true comfort to learn that in the end no child’s birthday cake was different from any other. This memory resurfaces often—cringe at the selfishness I harbored in that moment—but mine was also a child’s rebellion in the face of a war that killed 150,000 people over fifteen years and stopped those who managed to stay alive from truly living.

The final time we left was in the fall of 1985, to the United States, when I was ten. My fourth-grade classmate, who sat behind me, asked if I was Mexican because I spoke with an accent. That January, the space shuttle Challenger exploded. It was announced on the school loud speaker and my teacher shed tears. I was confused and held my breath. Someone asked how many people died. I sighed with relief when I heard it was seven. Only seven. I understood that day, from the emotion around me, that these kids, along with my teacher, had not been around much death. Also, that seven was indeed seven lives too many.

I’ve travelled back to Lebanon frequently over the years, spending the majority of my time in our village up north. But in March 2016, I came with a specific purpose: to cover the Syrian refugee crisis and social issues in Lebanon. This was the first time I lived in Beirut as an adult, and an attempt to regain a part of my identity—of being Beiruti, and being Lebanese. I rented a room in Furn el Chebbak (East Beirut) because it was surprisingly affordable and close to my old neighborhood.

But much of my time was spent in Hamra, which a relative of mine kept referring to as “West Beirut.” During my East Beirut childhood, the words “West Beirut” brought on a fear of the unknown, the enemy. Certainly I didn’t imagine the Hamra I came to know as an adult. The place my new friends—who helped me with everything from accessing refugee camps to finding a replacement car mirror for one I accidentally smashed on a rental—live and work in.

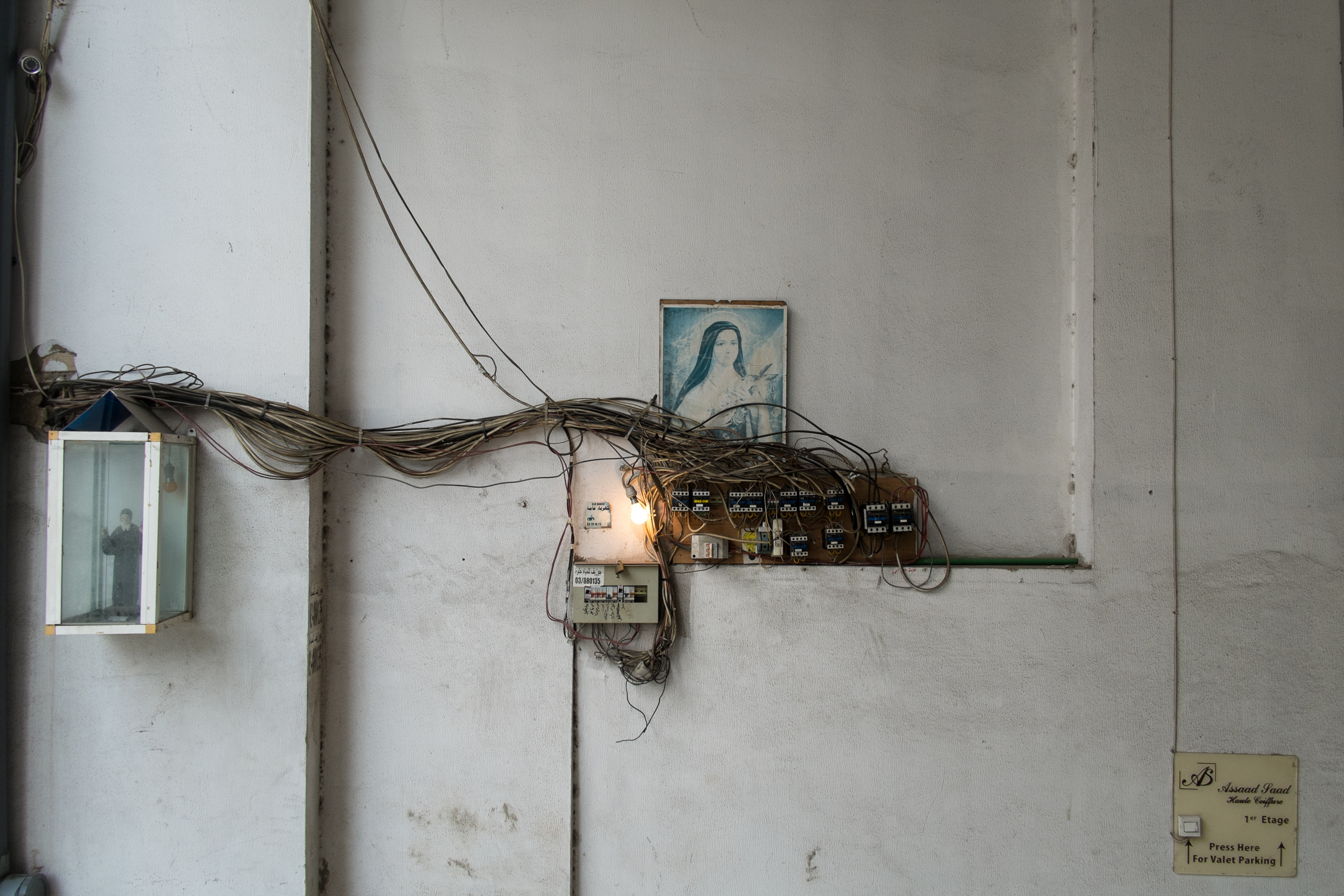

In my first days I came to Hamra by taking “a service.” That’s the Lebanese term for sharing a cab—a decades-old Uber pool. Negotiating with the driver before getting into the car is often like dating on Tinder. You lean in, check each other out, keep expectations low. You tell the driver where you’re headed. If he (most drivers are men) raises his head and eyebrows, it’s not a match, and he’ll drive off. If he nods or waves you in, it’s a go. Later, when I realized that most drivers in Furn el Chebbak didn’t feel like dealing with Hamra’s traffic, I learned to take the number 4 bus from Tayouneh, really a van which costs 66 cents. The sliding door is often left open, tied with a rope. Women generally sit next to women, and men next to men. The driver will keep either a rosary hanging on the mirror or Muslim prayer beads, with “Allah” written in sticker form on the window. Accidents are common.

I took a service for the last time at the end of my stay, having missed the bus. “Your tongue is heavy,” said the driver, meaning that I had an accent. My northern Lebanese accent, which I perfected with relatives in Buffalo, New York, is underscored with a bit of an American twang. “Where are you from?” he asked. I told him I was from Beirut. When he didn’t follow up, I added: “I’m also from a small village up north and am an American.” I expected him to question why on earth I’d chosen to come back to Lebanon—I was used to that response—but he didn’t. He said: “Ah, so the world is your home! Well, welcome home.”