When does writing become more than writing—expanding beyond a solitary act of artistic survival and into a roadmap for others trying to survive in an ableist society?

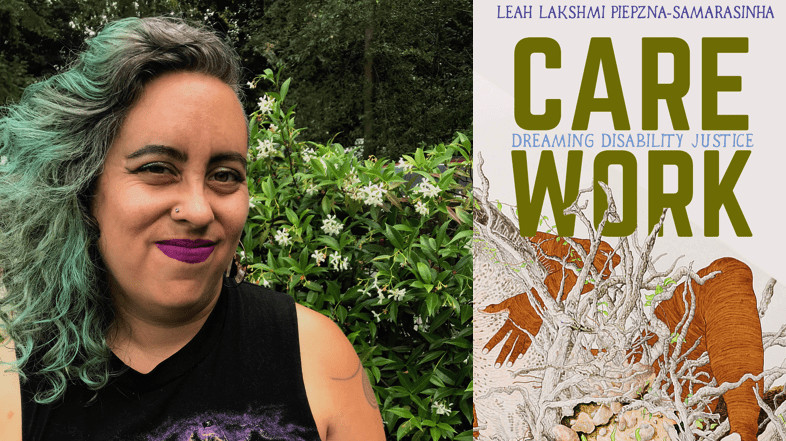

This is the nexus of Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s work. As a queer disabled femme of color writer, performer, and activist, Piepzna-Samarasinha has decades of evidence revealing her priorities as a community writer for disability justice. After three books of poetry, a memoir, and co-editing a groundbreaking anthology about transformative justice and abuse in activist communities, their latest book, Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice (Arsenal Pulp Press) offers a new curvation in genre-bending. In the way music overlays new beats on familiar lyrics, Care Work sands and buffers political multiplicities into one vinyl sound: reportage with theory, history with cultural criticism, and stylistic utility over formidability. Piepzna-Samarasinha’s latest, Care Work is a rock album addition to an impressively growing portfolio—an unflinching descent into the underbelly of racist ableism and erasure. Care Work is a collection of essays, each one laying groundwork for an anti-disposability politic that makes us question the cultures of speed and convenience that have shaped our society and public policies.

Piepzna-Samarasinha and I have a history of collaboration. I first learned of their work with Sins Invalid, a performance project that celebrates artists with disability, with particular emphasis on performers living in marginal and erased communities. An excerpt of her memoir was published in my first book, an anthology, Dear Sister: Letters from Survivors of Sexual Violence. After serving as the editor for a feature essay they wrote about building an economy of care, they asked me to serve as book editor for this project, wanting to work with another person of color after years of working with racist and otherwise oppressive editors. By the end of this literary feat, after I studied their choices in language and rhetoric, I see how their work raises the standard for writing and artistry: Piepzna-Samarasinha writes in non-white English, which means un-standardizing language norms and writing in accessible, precise, and vibrant provocation.

Our correspondence is often done via email. In the tradition of prioritizing process over product as an anti-capitalist practice, we created a collaborative space that intentionally accommodated disability, motherhood, neurodivergency, and fatigue.

—Lisa Factora-Borchers for Guernica

Guernica: Care Work is your sixth book: What do you hope this book accomplishes or reaches that is distinct from your previous works?

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha: After Dirty River came out and blew up more than any of my other books, I wanted to write a book like Dorothy Allison’s Skin: a big-ass, juicy compilation of all my essays—and I thought, Wow, for the first time, I might not have to beg someone to publish my work. I thought it was going to be easy—I’d just knock together every blog post and essay I’d written and voila, a book. Then, as I started working on it, I saw there was a theme–all of the pieces were about disability justice in some way. Then Trump happened, and everyone in my life, especially every single disabled person I knew was scared shitless that the fascists would murder us and that mainstream activists would be oblivious. So the purpose of the book got sharpened. I wanted to create a tool that would be useful for our communities to learn how to deploy disability justice so we could survive together.

Guernica: One of the things I am drawn to in your writing at large, is that community repeatedly emerges as a central theme. What impacts your community impacts your writing.

Piepzna-Samarasinha: For sure. After Trump won the election, some of my queer disabled friends in Seattle had a series of freaked-out meetings where we talked about things like where can we all meet if wireless goes out, the list of cars we can carpool in to get to Canada, and our self-defense plan. Then, when the 2017 and 2018 West Coast wildfires happened, the sick and disabled queers were the ones telling everyone else how to get masks and detox herbs and air filters—because that is knowledge we already had. All of it made me think about how disabled Black and brown, queer and trans people have been changing the world and building this movement for a while—-that we have this knowledge we need and the world needs to survive fascism, ableism and climate chaos, and that it might be helpful for me to publish the pieces I’ve written to contribute to that.

Guernica: Care Work prioritizes the survival of your communities and that also seems to be a major determinant in your literary and publishing decisions.

Piepzna-Samarasinha: At one point, I had someone at a major publishing house hit me up saying, “We love your work, and we think it’s time for a book on disability justice!” They were actually offering more than $800, so I thought, Amazing, maybe I can pay off some of my student loans. I pulled back because I did not in any way feel okay about the idea of selling out the intensely collective, grassroots movement of Disability Justice that I am a part of by passing myself off as some kind of “leader/expert,” which is usually part of what is asked of you if you’re trying to sell a book of essays on a major press. As a light-skinned, ambulatory person, I was also conscious of the privileges I hold with the disabled community and I was like, I do not feel right about potentially being seen as “the face of Disability Justice”, given that. As a cultural worker, it’s important for me to act from a place where you can consciously reject the machine’s desire to make money by elevating you as the one, special one. I want to be part of a big multiverse of stars who reflect each other. So I went with Arsenal Pulp, the Canadian indie queer press that published Dirty River and continues to knock it out of the park by publishing QTBIPOC writers like Joshua Whitehead, Kai Cheng Thom, Larissa Lai, and more.

The process of getting the book into the world has been really wild. I had to fight hard to buck so much racist ableism to keep my voice intact, and to not write like I was “explaining Disability 101” to abled people (which is not my goal as a writer). Andm\, interviewers and people in the publishing process did not believe that disability studies was a real category–like many disabled writers, I kept getting interviewers saying, “Do you want to say more about your disability?” in that creepy tone, and then they would get really confused when I would talk about disability community, politics, family- because for so many abled people, those things don’t exist, we’re just a bunch of tragic health defects.. Then the entire first run sold out in six weeks, which never happens to most books (especially to weirdo mix tapes by and for disabled femmes of color who swear a lot) and every event was sold-out, including one with two hundred people who came out in western Massachusetts on a Monday night. People were so damn hungry for the book. I’ve had some great reviews and got on some “Best of” lists, but there’s also this echoing silence, both from white disability studies land, who continue to be pissed that disabled Black and brown writers and activists continue to do our thing without their permission, and from non-disabled activist land, who often continue to stare blankly at us. And then there’s all the people who are like, I read your book in the psych ward, or I bought twenty copies to give to my mosque, or or who are people of color tell me that they’ve always been closeted about their disability but the book changed that, and I’m like, Okay, I think I got it pretty right.

Guernica: You are a nonconformist in many ways. In the book you quote Patty Berne, “Disability Justice…[is] an honoring of the longstanding legacies of resilience and resistance which are the inheritance of all of us whose bodies or minds will not conform.” How does the ethos of nonconformity influence your creative choices as a writer?

Piepzna-Samarasinha: Disabled people’s bodyminds are nonconformist by nature: dis like, dissident, like dissent. I have always been a community-based writer. I wouldn’t be daring to write about disabled people, disabled struggle and life and joy and skill, without apologizing or translating it to the lowest common denominator, if it wasn’t for the disability justice movement, in particular Sins Invalid, boldly making disabled Black and brown queer, kinky cultural performance art since 2005. When the queer writing spaces you see are all white, you don’t get the sense you can make QTPOC writing and anyone will get it or care. Before Sins, I was disabled forever but was like, Oh, that won’t go over at the slam, that’ll just be depressing to people. One of the things I am proudest of is getting feedback from other sick and disabled QTBIPOC writers that my work helped them know they could write their stories.

I am one of many disabled writers writing against the complete erasure by literary communities of disabled writing by disabled writers. If I had a dollar for every time an editor has assumed that no one sick or disabled reads or that no one will know what the word “ableism” means, I’d be able to pay off my student loans. There’s an overwhelming assumption on the part of editors that the only disabled stories are tragic or inspirational or heartwarming or about dying—best of all if they’re all of the above! And that there’s no such thing as crip histories or disabled literary history. In an essay, I once wrote: “One of the strengths I find in disability communities is…” and an editor commented, “Do you want to say more about your disability?” She couldn’t comprehend that I was talking about disability as a culture, as communities, as inside language and beautiful complex stories and weirdness and love and comedy and resistance—as anything other than me doing a “My name is Leah! I have fibromyalgia! I know you maybe have not heard of it, but let me explain what it is! Life has challenges, but I keep a great attitude!” kind of Reader’s Digest bullshit.

I am so proud of coming from and contributing to a collective lineage and peer group of disabled, sick, neurodivergent, deaf and mad writers. I want to be one of many people announcing that this is a tradition and a way you can be a writer, to be part of creating a disability justice literature.

Guernica: Who are some of the writers in that collective lineage?

Piepzna-Samarasinha: So many people! But off the top of my head, some of the writers I can think of include: Leslie Feinberg, Gloria Anzaldua, Laura Hershey, Audre Lorde, among many other people, and to be part of a breathtakingly gorgeous crip lit present that is not all white (uh, hardly) and includes writers and creators like Aurora Levins Morales, Cyree Jarelle Johnson, Rodney Divertus, Syrus Marcus Ware, Lynx St Marie, Patty Berne, Leroy Moore, Mat Fraiser, Rodney Bell, Kai Cheng Thom, billie rain, Heidi Andrea Restrepo Rhodes, Arlene de Souza, Maria Palacios, Carolyn Lazard, Alice Sheppard, Alice Wong, Qwo Li Driskill, Tara Hardy, Lydia X Brown, Juba Kalamka, Neve Kamilah Mazique Bianco, Stacey Milbern, ET Russian, Maya Chinchilla, Elena Rose, and a million other people, including people I don’t know yet.

A disabled literary tradition, to me, means you are innovative, resourceful, bold, Crazy brilliant, writing from both a collective and individual space. It can mean you’re able to be incredibly honest about body/mind experiences that most people are too squeamish to write about. There is a huge, under-documented tradition of fiercely unapologetic disabled writing and I am proud to be a part of it. I am proud to be a disabled femme of color writer, writing in a disabled way.

Guernica: One of my favorite images you write about in Care Work is the function of the bed. I think that when able-bodied people think of beds in relationship to disability, they would think limitation and rhetoric like “bedridden.” But you write a powerful juxtaposition: the bed as the place where you may collapse in fatigue or sickness, but it’s also where your ideas and creativity expand. It’s where you often work. Can you talk a bit about your writing practice and how the function of place influences your writing?

Piepzna-Samarasinha: Yeah dude. I wouldn’t be the writer I am if I wasn’t sick and disabled and Autistic and nuts.

People are always like, “You’re so prolific!” and I always want to say, “You know, being sick and weird can be a great way of having a hell of a lot of time to write.” 9-5 job not accessible? Welp, I guess I’ll get real good at lentils and hustling self-employment while making things, like books. It’s kind of like being poor: If you don’t have anything to lose, like middle class respectability, you can dare to make a lot of crazy shit happen on one dollar. I’m not trying to romanticize poverty or disability, obviously there’s a lot of shit that’s hard about both because of ableism and classism. I do want to assert that there are dissident kick-ass possibilities being a disabled, working class writer can unlock, that abled and middle class writers may lack.

The way I’ve been writing since I started writing is often writing in dream time, in crazy time, in time when I’m supposed to be doing something else. I write on the bus, in the waiting room, in between part-time independent contractor artist hustle crip jobs. I’m also really disciplined as a writer and I want to say that because there’s so much work we do as disabled BIPOC people that is erased. I broke up with a friend once because when I was like, No I can’t go to brunch, I’m working that day, she snorted and was like, “What kind of work could you be doing?” I work really hard–in a disabled way–and I don’t have time in my life for people who can’t respect that I write from bed on a heating pad. I take breaks. I hyper-focus. I jerk off in between bits. Being crazy and sick makes room to just write your own damn reality because, fuck it, why not, and, being close to death and extreme states gives you the ability to not waste time and get really real about things. This is a set of possibility models for being a writer that is relevant and useful for other sick, disabled, mad writers and also for any writer who’s trying to figure out how to write if they don’t have a trust fund or a rich partner or a room of their own in a castle.

Guernica: What’s up next for you, and how did Care Work shape you going into your next projects?

Piepzna-Samarasinha: Well, it’s kind of ironic because, I wrote this disability justice book, part of which is me going on and on about revolutionary slowness and crip time and sustainability, right? And then there was this whole “hit the road for nine months” push of touring, which I feel really proud that I pushed back against and toured slowly and sustainably, and the book still has been a success. But what happened was, not only did Care Work come out, but Arsenal Pulp also said yes to publishing my fourth book of poetry Tonguebreaker, which came out six months after Care Work, in March 2019. Then Ejeris Dixon and me got this bright idea to work on a book compiling actual resources about HOW to do transformative justice/not call the cops, because it felt like TJ and anti-police brutality activism had gotten to this critical mass where a lot of people were like “OK, I know calling 911 may result in my death, but I have no idea what to do instead that’s not just a bunch of ‘Call on your community!’ rainbow and butterflies stuff.” This became Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories from the Transformative Justice Movement, which will be out on AK Press in January 2020. It has all kinds of toolkits talking in very frank, real-life terms about things like how you can defend your community from ICE, how to support someone having a psychiatric crisis without calling the cops, some ways Trans Lifeline supports suicidal people without calling 911, interviews with Black, Native and Asian sex workers talking about the creative ways their communities keep safe and deal with violence without police, the details of an Indigenous community lead murder investigation that worked when the cops didn’t, and ways to support both survivors and perpetrators of sexual assault and partner abuse and childhood sexual abuse.

Then Bear Bergman asked me if I would write a kids’ book, for his and his partner j.wallace skelton’s micropress, Flamingo Rampant, which publishes children’s books where everyone is queer and trans and there is no Big Depressing Storyline, but just kids being awesome. The working title is Bridge of Flowers and I’m still figuring it out, but basically it’s a big queer of color family where everyone is sick and disabled and the parents are a witch and a scientist who live in different homes. Then one of their ramps breaks and the kids have to figure out creatively how to fix it together. I just wanted a world like my own in a kids’ book: where everyone is sick, weird, disabled, gay and trans as hell and Black and brown, and just kicking it.

Three new books. And teaching writing. But also, continuing to survive, be happy, thrive, fuck, sleep, eat, go for walks, love my chosen fam, and be a part of ending the white supremacist capitalist colonialist ableist patriarchy in this lifetime. One queer femme crip of color writer at a time.