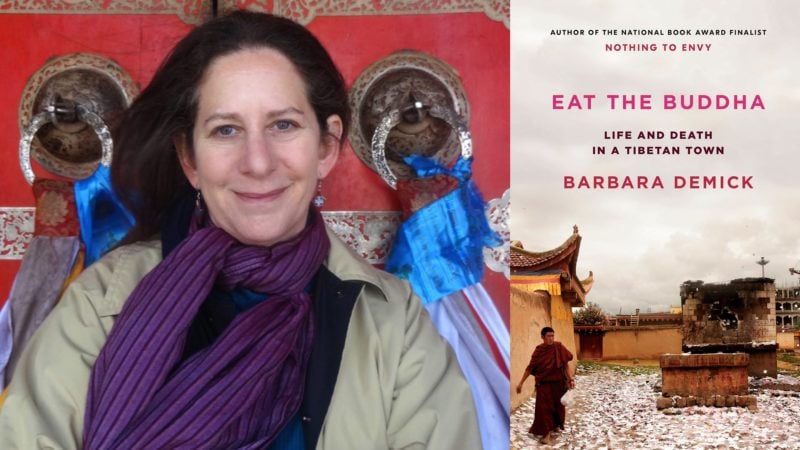

One lesson to be learned from Barbara Demick’s books is that peace and prosperity are fragile—society can fall apart at any time. Demick, who has more than twenty-five years of experience as a foreign correspondent, has spent her career writing about people living in places torn apart by violent change. In her first book, Logavina Street, she writes about the Bosnian War by telling the stories of the inhabitants of one street in Sarajevo. Her second book, Nothing to Envy, a finalist for the National Book Award, offers a glimpse into the daily lives of North Koreans. When Demick moved to China in 2007 as the Beijing bureau chief for The Los Angeles Times, she turned her attention to Tibet. Now she has published her third book, Eat the Buddha, which focuses on a town in Eastern Tibet after the Communist takeover in 1951.

Not long after Demick’s arrival, Tibet erupted in anti-government protests that were swiftly suppressed, with increasing surveillance and military presence. But Tibetans found another way to express their dissatisfaction: Since 2009, 159 Tibetans have set themselves on fire in protest. Nearly a third of them came from one eastern border town, Ngaba, which is administratively part of Sichuan Province. Ngaba came to be known as the capital of self-immolations. In Eat the Buddha, Demick explores the lives of Tibetans from this town by talking to people like Gonpo, the daughter of the last king of Ngaba, who lost her family during the violence of the Cultural Revolution and who later became a Communist Party member; Tsegyam, a poet and teacher who secretly agitated for independence; Norbu, an orphan who rose from homeless street hustler to wealthy entrepreneur; and Dongtuk, a monk closely related to two of the self-immolators. The people Demick portrays try to make peace with the present while carrying the pain of decades of trauma and loss.

—Judith Hertog for Guernica

Guernica: Of all the places in China you could have written about while you were the LA Times bureau chief in Beijing, what made you want to write about Tibet?

Barbara Demick: I was actually an accidental China correspondent. I had asked to be in Paris because I wanted to report on North Africa, but the newspaper decided to send me to Beijing. I initially felt intimidated because there were all these other reporters who were fluent in Chinese, and there were already so many books on China. I felt that the eastern part of China was already extensively covered, so it seemed to me I had to go out west if I wanted to cover stories that hadn’t been told before. It’s not that I was a Buddhist or that I was fixated on the Dalai Lama. I actually didn’t know all that much about Tibet at first. But I’m attracted to the places in the world that aren’t easily accessible, that you can’t discover on Google Earth. I visited the Tibetan plateau for the first time in March 2008, right after there had been protests there. I took a shared taxi with these chain-smoking nomads and we were driving over the hills and I was feeling very nauseous, and I thought: This is great! It’s a very foreign-correspondent reaction: The more challenging it is to get somewhere, the more I want to know.

Guernica: So was it difficult for you, as a reporter, to gain access to Ngaba, the town you wrote about in your book?

Demick: If you’re a tourist with money, you can go to Tibet easily, but for journalists it’s very difficult. They [the Chinese Government] don’t give journalists permits to travel to the Tibetan Autonomous Region unless it’s on a government-sponsored tour. But Ngaba is in Sichuan and isn’t included within the Tibetan Autonomous Region. More than half the Tibetan population in China lives in border regions outside the Tibetan Autonomous Region, in provinces like Sichuan or Yunnan or Gansu. And, in theory, you do not need a permit to travel to those areas. Though when you actually arrive, you often find a roadblock and are told you can’t go there.

Guernica: Did the Chinese authorities know you were traveling there as a journalist?

Demick: They didn’t know I was there, period. I wasn’t exactly “sneaking in,” but I didn’t announce my presence. I would fly to Chengdu and then travel by taxi or private car. I would wear a big hat and a facemask—which many people there wear because it’s dusty and the sun is harsh—so I wasn’t easily recognizable as a foreigner. Now that surveillance has increased, I don’t know if I would be able to travel like that again.

Guernica: What about Ngaba turns people so desperate that they burn themselves in protest?

Demick: I don’t think there is one answer as to why people do this. Of course, when suicides happen they often happen in clusters. But there are several things that are unique about Ngaba. It was one of the first places where the Chinese Communists encountered Tibetans during the Long March in the 1930s, when the Red Communist army had to retreat from Eastern China. They ended up on the Tibetan plateau, and these famished Red Army soldiers, who spoke no Tibetan and didn’t really understand where they were, plundered the storerooms and the fields of Tibetan villages. Ngaba is also on the eastern edge of the Tibetan plateau, where Tibetan and Chinese culture collide, and these collision points experience a lot of unrest.

This area has a history of resistance and guerilla warfare against Communist rule going back to the 1950s and 1960s. When the Communists invaded Central Tibet, they signed an agreement in 1951 that they wouldn’t interfere there. But Eastern Tibet was right away slammed with the most ill-conceived of Mao’s policies. The Han Chinese Communists Party didn’t know anything about that region, like how to raise yaks, or that at a height of 3000 meters, you can’t grow any grains beside barley. So the mistakes they made in Eastern Tibet were even more disastrous than the mistakes they made in China.

There were famines, ethnic cleansing, roundups of people into communes, imprisonment or eviction of local leaders, and confiscation of property. Many people from eastern Tibet fled to Central Tibet, and it was the pressure from the eastern Tibetans and the resulting uprising that led to the flight of the Dalai Lama [in 1959]. But much of this is not well known, because many of the Tibetans who fled into exile were from central Tibet, and they were the ones writing memoirs and books. All this is part of the seed that made Ngaba ready for this wave of self-immolations decades later.

Many of the self-immolators actually descend from fighters who participated in the uprising of the late 1950s. One example is this young monk named Phuntsog, a friend of one of the people I portray in the book, whose self-immolation in 2011 launched the wave. His younger brother self-immolated a few months later but survived. Their grandfather had been one of the anti-Chinese resistance leaders in the 1950s and became a local hero after surviving 18 years in Chinese prison camps. The older generation had been fighters, but the younger generation had internalized the Dalai Lama teachings about nonviolence, so they couldn’t bring themselves to kill anyone but themselves.

Guernica: The title “Eat the Buddha” refers to the story about famished Chinese Communist soldiers during the Long March in 1934 who ate the votive offerings (tormas) in Tibetan temples. It’s a strong metaphor.

Demick: The title symbolizes the devouring of Tibet. These Chinese soldiers knew they were doing something bad, but they were hungry. Of course they were not monsters. There are stories about Chinese soldiers who would leave IOUs for the food they took from Tibetan villagers because they were idealistic Communists who didn’t want to steal from the poor. But of course, those IOUs were never paid back.

Guernica: The Tibetans you portray are not unequivocally negative about the Chinese government.

Demick: I have tried to provide a nuanced view. First of all, there is some common ground between socialism and Buddhism. Many Tibetans sympathize with socialist ideology, including the Dalai Lama himself, who calls himself a socialist at heart. So, there were some Tibetans who embraced the Communist Party in the early years. In a material sense, many—if not most—Tibetans in Ngaba are better off than in the past. But it’s not all about the economy. People also want to have the freedom to travel, use their language, preserve their culture, practice their religion, and speak their mind. A very successful Tibetan businessman from Ngaba told me that he has everything he can possibly want in life, except for freedom.

Guernica: How do you see the future of Tibet?

Demick: I don’t see the near future as being very positive. The current Chinese leadership under Xi Jinping is all about control. They have taken the tracking tools they’ve developed during the COVID lockdown—these apps that record where you are and who you see—and are using that technology to increase surveillance.

But in the long run, China tends to go through cycles of tightening and liberalization. After this current cycle, I’m not sure everything will remain negative for Tibetans. Nowadays, many young Chinese feel that something is missing in their own culture and are looking to Tibet for spirituality. There’s this wave of “tantric fever” in China, of Han Chinese who have become devotees of Tibetan Tantric Buddhism. This may inspire a new respect and appreciation for Tibetan culture in China.

Also, Tibetans are not as anti-Chinese as one might expect. For instance, one of the people I portray in my book is Gonpo, a Tibetan princess from Ngaba who lost her family during the Cultural Revolution. Despite everything she endured under Mao, she married a Chinese husband and joined the Communist party. Eventually, she ended up living in Dharamsala and now works for the Tibetan government in exile. But she says she still loves China, and she still speaks better Chinese than Tibetan.

I think that under a more liberal government, Chinese and Tibetans can live together peacefully. Eastern Tibet, from the 1980s and 1990s until the beginning of the protests in 2008, had actually been quite peaceful. The schools taught in Tibetan, there was a relatively free intellectual life, and people had freedom to worship. But in 2008, the Chinese government tried to exert more control over the monasteries and over Tibetans’ freedom of movement. It’s the heavy police presence that’s causing the problem.

Guernica: Earlier this year China expelled reporters from The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal. Do reporters self-censor in order not to lose reporting privileges?

Demick: The censors don’t read the stories that carefully. There are certain subjects that are sensitive—the wealth of Chinese Communist Party leadership is a sensitive issue—but the way those journalists were expelled was really just tit-for-tat against the Trump administration. But what reporters are nervous about is getting sources in trouble. A friend of mine at The Washington Post just wrote a piece about a trip to Kashgar and was afraid to talk to anybody there because she didn’t want to get them in trouble.

Guernica: How did you deal with this when you reported in Ngaba?

Demick: The last time I went to Ngaba was in 2015, but I haven’t wanted to go back because I don’t want to get anyone in trouble. You never know when people will get punished for having talked to you as a reporter. It’s risky. Sometimes I’d talk to someone who wanted to take a selfie with me to post on WeChat. I couldn’t warn them that I was a journalist, but I knew they could get in trouble for being associated with a journalist.

Guernica: Some of the Tibetans in your book now live in exile in India. Is that because you could talk more freely with Tibetans in exile?

Demick: Well, even Tibetans in the exile community have to be very careful because they are afraid of causing trouble to their remaining family. Besides, the Chinese government controls whether Tibetans who live in exile can go back to visit their family, and they won’t grant you a visa if you’re at all involved in any activism or journalism.

Guernica: Does knowing that Chinese government censors may read this interview make you more careful about what you say?

Demick: I’m careful. But it’s not just a matter of not wanting to offend the Chinese government; I want to be fair to Chinese people. There are many Chinese who don’t really understand what happened in Tibet because they’ve only been exposed to propaganda. They have heard about how much money the Chinese government has invested in Tibet, but they don’t learn about the suffering Communist policies have caused in Tibet.

Guernica: Is focusing on the stories of individuals, both in this book and your book on North Korea, your attempt to counter the erasure of individualism under totalitarian regimes?

Demick: It was really about how to tell a story in a way that readers will respond to, challenging stereotypes and building empathy for people who may seem foreign to many readers. Until my book on North Korea came out, there had been very little that showed North Korean people as anything other than automatons goose-stepping in support of Kim Il-sung, and Kim Jong-Il, and Kim Jong-un and the regime. It was almost this racist stereotype of the inscrutable Asians.

Now, Tibetans have been portrayed more sympathetically, but they are often seen as clichés—you know, the holy man on the mountain, or the rugged nomad, or the members of this crazy religion—but not necessarily as regular, contemporary people who have concerns that readers can identify with. I really wanted to look at Tibetans in the 21st century and know what their concerns are and how they continue to exist as a people.

Guernica: Your book on Sarajevo, Logavina Street, uses a similar structure of interwoven personal narratives.

Demick: I want to portray history through the eyes of the people living it. I write primarily for an American audience, and, you know, Americans can sometimes be rather closed off to the outside world. When I started that project about Sarajevo, they were already a year into the war, and I sensed that Americans were experiencing so-called “empathy fatigue.” So, this was a way to get readers to care. In Logavina Street, someone asks: “What would Americans do if their food supply, their electricity, their heat, their water were all cut off, and you live in the middle of a city?” And the same was true of my North Korea book. What would you do in New York if all the food suddenly disappears? Would you go out to Central Park to look for edible grasses and catch pigeons?

Guernica: In April this year you wrote an op-ed in the LA Times about how the COVID pandemic in the US reminds you of the way people acted during crises in Sarajevo and North Korea.

Demick: I don’t really worry about something like the lack of toilet paper. That’s a first-world problem. But I do worry about the divisions and the violence. When I think about the polarization of the US under Trump, I think a lot about Bosnia. One of the women in Sarajevo, her name was Jela—she was like my Sarajevo mother because I lived with her and her husband—when she talked about the war, she said that people have become so evil it was “as if they drank blood.” And that has always stuck with me. Now, when I see people getting into fights over things like masks and vigilantes attacking protestors, with some of this violence supported by actual police forces or by the government, I worry that the civility that holds society together turns out to be very thin.

Guernica: Do you ever want to write a book about the US?

Demick: I would like to write about the US. But it’s funny, I now feel like a bit of an outsider here. I’ve lived abroad for twenty-two years. I have another book about China coming out in a year or two. It’s quite different. It’s about separated twins. When I reported on baby girls who were adopted from China. I learned that many of them had not been given up by their parents but were confiscated by local government officials because the parents couldn’t pay the fines for excess births [in transgression of the “one-child” policy]. I found a family who had twin girls, one of whom was taken away and ended up being adopted by a family in Texas. The other girl grew up with her family in rural Hunan province.

Guernica: In that LA Times op-ed you wrote: “Wars, famines, natural disasters can bring out the best in people, releasing untapped reserves of strength that turn ordinary people into heroes.”

Demick: Yes, it’s very interesting to me to understand who the survivors are. One of my favorite people I’ve written about is Mrs. Song, a North Korean woman who was a true believer in communism but who then became a successful free-market entrepreneur because that was what she had to do to survive when her factory closed. Her husband, her son, and her mother-in-law all died of starvation, but she was just so strong and had such a will to live and survive. She escaped to South Korea. I still stay in touch with her and saw her again last year. Every time I visit Seoul, we go out for a nice meal and ice cream.

Another such person is Gonpo, the Tibetan princess. Even after having lost her family many times over, she is still not defeated and is still able to find joy. Some of my favorite people are not particularly well educated or sophisticated, but they are really, really good at living. Every foreign correspondent will say this: You go to the most far-flung places in the world and the most complex situations, and it turns out people everywhere care about the same things: feeding their children, educating their children, fixing their homes, taking care of their parents…We are all kind of the same.