What can a California geographer possibly teach us about the American troop surge and ethnic cleansing in Iraq?

The middle of September was a rotten time to challenge the dominant media narrative on the Iraq war. The success of the surge appeared confirmed by a long decline in deaths, both American and Iraqi, and by the man running the war, with whom Senator John McCain has uniquely shared credit, General David Petraeus. Even Senator Barack Obama, whose brand was launched in part for his consistent opposition to the war, confirmed the surge’s success in a Fox News interview, saying the “surge succeeded beyond our wildest dreams.” So Dr. John Agnew’s report, “Baghdad Nights: evaluating the U.S. military ‘surge’ using nighttime light signatures,” which challenged the basic premise of the surge’s success, was a little like arguing a call made in Game Six of the World Series, while Game Seven was well underway. It didn’t help that the report landed exactly three weeks after the splashy announcement of Alaska Governor Sarah Palin as Senator McCain’s running mate, and about a week and a half after the equally explosive news of a possible U.S. economic meltdown. Neither timing nor momentum was on Agnew’s side.

The middle of September was a rotten time to challenge the dominant media narrative on the Iraq war. The success of the surge appeared confirmed by a long decline in deaths, both American and Iraqi, and by the man running the war, with whom Senator John McCain has uniquely shared credit, General David Petraeus. Even Senator Barack Obama, whose brand was launched in part for his consistent opposition to the war, confirmed the surge’s success in a Fox News interview, saying the “surge succeeded beyond our wildest dreams.” So Dr. John Agnew’s report, “Baghdad Nights: evaluating the U.S. military ‘surge’ using nighttime light signatures,” which challenged the basic premise of the surge’s success, was a little like arguing a call made in Game Six of the World Series, while Game Seven was well underway. It didn’t help that the report landed exactly three weeks after the splashy announcement of Alaska Governor Sarah Palin as Senator McCain’s running mate, and about a week and a half after the equally explosive news of a possible U.S. economic meltdown. Neither timing nor momentum was on Agnew’s side.

But obviously the surge was still a part of the foreign policy experience the McCain campaign has been touting, in a sense their most dramatic edge on Senator Obama. In their first debate, on September 26, Senator McCain again hailed the surge’s success and his role in pushing for a new strategy. Prompted by moderator Jim Lehrer, Senator McCain summed up the lessons of Iraq like this: “I think the lessons of Iraq are very clear… we went in to Baghdad and everybody celebrated. And then the war was very badly mishandled. I went to Iraq in 2003 and came back and said, we’ve got to change this strategy. This strategy requires additional troops, it requires a fundamental change in strategy, and I fought for it. And finally, we came up with a great general and a strategy that has succeeded. …And we are winning in Iraq.” But Agnew’s report, which got scant notice, purports that simply isn’t so. And McCain’s star general and point-man, Petraeus, knows it, too.

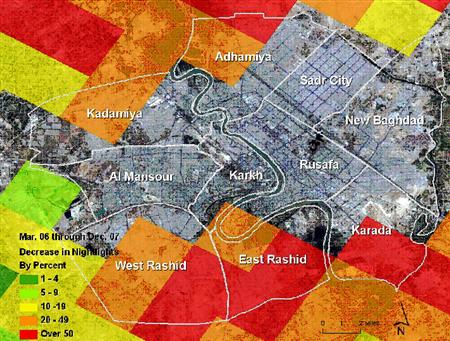

In early 2008, Agnew, a specialist in geopolitics, international borders, and ethnic conflicts, looked with his team at a series of satellite images of Baghdad and other Iraqi cities taken at night. The project was born as a course on remote sensing taught at UCLA by Agnew’s colleague, Thomas Gillespie, who, along with Agnew and their students, also had an interest in the urban consequences of the invasion of Iraq. The images showed that in neighborhoods with mixed sects, the constellations of house lights (what geographers call the “light signature”) weren’t coming on at night over time. Even as Iraq got its infrastructure back and recovered its light signature as a whole, its neighborhoods of mixed sects never returned to full brightness, but appeared forever dimmed. After comparing those neighborhoods with a military report that cited the same areas as sites of ethnic cleansing, Agnew’s team found they were left with one rather grim conclusion. The surge happened after Iraq’s mixed neighborhoods had already been homogenized, rival sects chased out or killed; the surge, as such, was almost utterly pointless, except perhaps politically, a key talking point in an election year. “Our findings suggest that the surge has had no observable effect, except insofar as it has helped to provide a seal of approval for a process of ethno-sectarian neighborhood homogenization that is now largely achieved,” Agnew’s team noted in their report.

This is confirmed, says Dr. Agnew, by reports coming from human rights groups describing which Iraqi neighborhoods the internally displaced and refugees had come from (matching those that were dimmed in perpetuity). It is also being confirmed now by news reports over the last few weeks of Sunnis or Shiites being targeted all over again as they attempt to reclaim their houses.

In a bluntly-named October 14 article (“Iraqis are being attacked and killed for returning to their homes”), McClatchy News reported: “Haj Ali’s family had been home for less than a month when a makeshift bomb blew off part of his garage. The message was clear: Go back to wherever you came from. ‘We thought it was safe,’ Ali said. ‘Now I see that for us, home means death. There are still people who don’t want us there.’” Perhaps most dramatically, it was confirmed by the U.S. military, particularly by the September 2007 testimony of General James L. Jones before Congress. But somehow, though it was very similar to General Jones’s, General Petraeus’s report cited sectarian violence, but failed utterly, as they say, to connect the dots.

—Joel Whitney for Guernica; Art by Emily Hunt

Guernica: So the premise of your report is that the surge’s main effect was ethnic cleansing in Iraqi neighborhoods?

John Agnew: Well, the surge came after the ethnic cleansing. That’s the main finding. So it’s rather like the surge happened after the main event. And so it really hasn’t had any effect. That’s our conclusion.

Guernica: Walk me through the process of drawing that conclusion from these satellite images.

John Agnew: Okay. Well, we looked at infrared images taken by a satellite that goes over places at night and records the light intensity. We were able to get this information for four nights, scattered over the period from 2003 until December 2007. That was the last one that we were able to get. (You can get these for anywhere in the world. These are not just specifically going over Iraq.) What we did was take it for a number of other cities in Iraq and for Baghdad. Our original intention was to see to what extent over the period after the invasion there was a decline in light intensity. And then there would be an increase in light intensity. Our interpretation being that this was a kind of surrogate measure for the electricity supplies to the cities of Iraq.

The hypothesis was that over time you would expect a diminution in the light, as electricity supply was disrupted, as everyday life kind of broke down, and so on and so forth. But then over the next period of time, particularly over the period of the surge, we were expecting to see something of a net improvement in light intensity, this being again an interpretation of the general condition of everyday life. But what we found was something quite different from that.

Guernica: Tell me what you found.

John Agnew: Initially after the invasion, yes, the light intensity went down for Baghdad as a whole. Then it went up a little bit. And then during the period of the surge, from December 2006 through 2007, we saw a real diminution. It started in December 2006 and didn’t improve. So our interpretation was that the surge didn’t make any improvement in the everyday life of the city as a whole. Do you follow?

Guernica: Yes. If infrastructure was being restored and people were safe in their homes, the light would return to its full intensity.

What we saw was that the neighborhoods where the light signature had disintegrated were the heavily Sunni and mixed neighborhoods on the western and southwestern parts of Baghdad.

John Agnew: Right. The other thing we tried to do was to try and partition the imagery, according to the neighborhoods that the U.S. military used so that we could get a sense of whether this was the whole of the city or find out if things getting better in some parts but not in others, and so on. This was technically hard to do, but we did it. Again, we saw that it wasn’t just the city as a whole, but in fact some neighborhoods held up very well or improved [in their light emission] over the course of time…

Guernica: So the increase in light that you expected over the course of time did occur in some neighborhoods?

John Agnew: Yes, it did occur in some neighborhoods.

Guernica: Suggesting that the electricity supply was coming back?

John Agnew: Yes. Exactly. And that things were improving. But in other parts, it just collapsed. It didn’t improve over the course of 2007. And the thing we noticed—what stuck out like a sore thumb—was that overwhelmingly in the western and southwestern parts of the city that light collapsed.

Guernica: What’s significant about those parts?

John Agnew: Initially, we didn’t know. We just noticed that the light was disappearing in those areas, or weaker. But in the eastern parts of the city, for instance, the light either was maintained or increased in intensity. And then what we discovered was the report of General [James L.] Jones of the U.S. Marine Corps, who had done a report for Congress in September 2007, in which he and his researchers had collected data on violent deaths in the city of Baghdad, and located the data on maps of the city. They also came up with an estimate of parts of the city that had changed their sectarian makeup, that had gone from being predominantly mixed in their religious affiliation to being predominantly Shiite or Sunni, those being the two main divisions. What we saw was that the neighborhoods where the light signature had disintegrated were the heavily Sunni and mixed neighborhoods on the western and southwestern parts of Baghdad. These were precisely the areas where a lot of the sectarian violence that General Jones reported had been concentrated in the summer and fall of 2006, which was before the surge began. So our interpretation was that the lights were out in these parts of the city in 2007 essentially because these were the parts of the city where the sectarian warfare had created the damage and killed people, destroyed the place, and forced people to leave. So that involved tying together our findings with those of General Jones.

Guernica: But isn’t it possible to presume that this is either a coincidence, or that, because of the fighting, those areas had more strain on their infrastructure?

John Agnew: Sure, that is certainly part of the story. There’s no doubt about that; I mean, that’s where the violence was concentrated. But this is also where reporters have said many of the refugees in other parts of Iraq and those who actually left Iraq came from. And they left very much during that time, late 2005 through the fall of 2006. And they’re overwhelmingly Sunni. So you don’t need to be a rocket scientist to figure that out. I mean, these were the people who were seen as most affiliated with the former regime; these were the people who turned out to be the victims of this violence in 2006.

Guernica: Did General Jones actually cite “ethnic cleansing” in his report?

[General Petraeus] made it seem as if there was all this violence, but that somehow it hadn’t led to any kind of shift in the residential neighborhoods in Baghdad.

John Agnew: Oh absolutely. Yeah, that’s what his report said. A large part of it was given over to what had happened in Baghdad in 2006-2007. And he showed that the violence peaked in November, December 2006. And then went down very very quickly after that. And partly that was because many of these neighborhoods had lost their Sunni populations—that was his argument.

Guernica: And has Petraeus said the same?

John Agnew: No. Well, yes and no. Maybe that’s a fairer way to put it. General Petraeus, in September 2007 when he testified before Congress, used some of the maps that General Jones had produced, but all he showed on the maps were where the violence had been concentrated in Baghdad. He didn’t show how the neighborhoods, as a result of the violence, had changed their sectarian complexion. So he completely ignored that.

Guernica: He whitewashed out the ethnic cleansing.

John Agnew: Whether that was his choice or someone on his staff, we don’t know. But he made it seem as if there was all this violence, but that somehow it hadn’t led to any kind of shift in the residential neighborhoods in Baghdad.

Guernica: John McCain has been touting Petraeus as a hero and saying that because of Petraeus’s grand strategy, the surge has worked so well. And the verdict is…

John Agnew: The surge was a bit like closing the stable door after the horse had gone. It did impose a kind of Pax Americana, but only after all the violence had essentially done it for them. There was already a kind of diminution in inter-sectarian violence. And they came and built concrete walls between neighborhoods and that has had a pacifying effect. There’s no doubt about that. But in a way, the violence was already going down before the surge started.

Anyway, counterinsurgency, from what I gather, means you’re putting your troops out there in the population, and you expect an increase in casualties. I mean, you expect to be actively involved in combat in a much more vigorous way than when you’re doing a kind of whack-the-mole strategy, which they were doing prior to the surge. But as we know U.S. military casualties have gone down—and why? Well, because there was a lot less violence. A lot less fighting.

Guernica: I understand that few news agencies picked up this story.

John Agnew: Reuters picked it up initially. I think it did get reported later by AP, but it was Reuters in the first instance and then in the second instance, the British science magazine The New Scientist; they posted a kind of press release on their website.

The surge was a bit like closing the stable door after the horse had gone. It did impose a kind of Pax Americana, but only after all the violence had essentially done it for them.

Guernica: Outside of that, was there much press focus on this? Because it seems like John McCain has been unchallenged in his assessments that the surge has worked.

John Agnew: We have gotten quite a few inquiries and the story has appeared in a number of papers; there was a story in the London Independent, it appeared on the LA Times website and a couple of other places. But interestingly, it didn’t get picked up in print in the U.S. Only small newspapers like the Cape Cod Times or a couple of other places. I think there’s a kind of tiredness about talking about Iraq. People seem to have taken up positions on one side or the other anyway—no one seems that interested in anything empirical. And the other strange thing is that our results are the same as the ones in General Jones’s report, which was made to Congress [in] September 2007, and which nobody seemed to take any notice of. That’s the strangest thing for me…

Guernica: I saw two stories today—one on how the sectarian violence is now aimed at Christians. And the other was about how those within Iraq who are returning home are finding that they’re still not welcome—they’re being chased back out and the violence is creeping back up. Have you been seeing these?

John Agnew: Indeed, I have.

Guernica: It would seem to support your claims.

John Agnew: Obviously, these are beyond our report since our last [satellite image] was in December 2007.

Guernica: Right.

John Agnew: But I don’t think that anything was finally settled. The one reason for keeping American troops there is because if they leave, you’ll probably see a return to the kind of sectarian violence that was there previously. But that’s kind of it, and it’s happening anyway. I don’t see any reason for keeping them there. They’re not gonna resolve the violence, not militarily.

To contact Guernica or John Agnew, please write here.