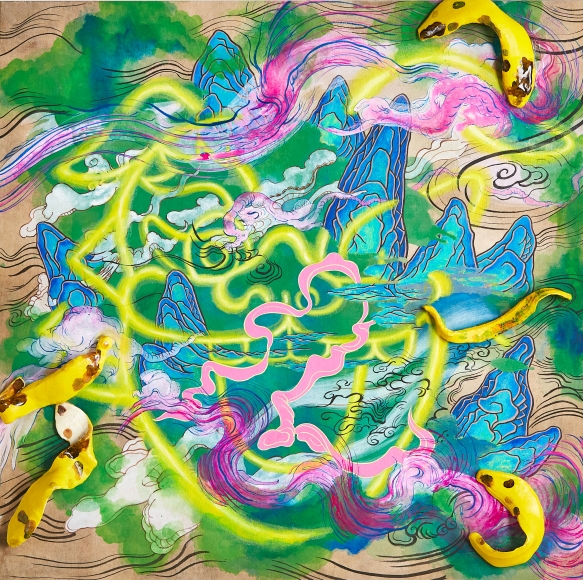

Jiha Moon’s evocative, sumptuous paintings are dynamic meditations on cultural identity. Her Yellowave series invites viewers to reconsider the color yellow, with its supersaturated neons that spill across the canvas in sweeping, freeform strokes, interrupted by detailed drawings of pagodas, trees, animals, and fruit. At once ancient and contemporary, these symbols reference both Eastern and Western culture. They are also a manifestation of Moon’s diasporic identity: she grew up in Korea and currently lives in Atlanta, Georgia.

Moon is known for integrating both ancient and pop culture references throughout her works, drawing from sources ranging from traditional brush painting to internet media. Her painting “Yellowave (Stranger Yellow)” incorporates these motifs alongside instinctive, gestural mark-making to create scenes that appear spontaneous but contain many nuanced layers of meaning. The painting was part of a series titled Stranger Yellow, lauded as an “artistic breakthrough” by critic John Yau in Hyperallergic for its stylistic novelty. Moon’s work has also been exhibited at Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, The Drawing Center, White Columns, and Asia Society. She has also had solo exhibitions at The Mint Museum, the Taubman Museum, the Cheekwood Museum, and elsewhere.

I recently saw Stranger Yellow at Derek Eller Gallery, and I was mesmerized by the energetic hues of Moon’s work. There is an electricity to the way Moon tackles questions of cultural fusion and immigrant identity. The combination of intense colors and elaborate detailing in her works make them feel like celebrations of the questions of who we are and where we belong. While Moon’s process is very spontaneous, there is a fascinating revision of cultural constructs in the way she passes images through Korean and American lenses to achieve hybrid final forms. I talked with Moon about how she creates her paintings, and how it is possible to see ourselves — or to see at all.

— Hua Xi for Guernica

Guernica: “Yellowave (Stranger Yellow)” is stunning in part because it’s so large and also so intricately detailed. Is it a long journey to create a work like this?

Jiha Moon: It took me about a half year to finish that painting. I started last July. That earlier version you see is from July.

For this painting, it kind of started as a reaction to the incident that happened in Georgia — the massage parlor shootings where six Asian women were shot. That event took place in the town I live in, and we actually live really close to where it happened. I was so shocked at the time. I was really getting depressed and feeling helpless as an Asian woman and also as an artist. That’s when I started to think about how to absorb what was happening and react in my artwork. The word “yellow” can be used as a derogatory term. But I wanted to use that color and turn it around and make it visible and loud and beautiful. Almost sunshine-colored. That’s how this series got started.

Guernica: Your images are suffused with giant waveforms, which feels like a new addition to your visual style. But would you perhaps see this “wave” element as a revision of your earlier aesthetics?

Moon: I am always interested in the idea of something that is very big and part of nature. Something that people have no control over. Nature can be really beautiful and also really scary. At the same time, I’m interested in the related notion of abstraction, especially visual abstraction. How do you paint something that doesn’t have a defined shape? Especially things in nature. For example, how do you paint the wind? A big wave? The temperature? Something that moves around? Or people’s feelings and emotions?

The brushstroke has been one of the forms that I investigate in my visual art. Before, I had been using brushstrokes to portray wind or a wave or a mood or other abstract elements. After the Atlanta incident, I began to think about a wave as a group of people, such as women or Asian people who live all over the place. In this series, the big brushstroke movements represent Asian Americans who live in this country or even all over the world.

Guernica: You painted this piece on hanji on canvas. Being handmade from mulberry pulp, hanji has, in my opinion, a far more delicate and clothlike texture than printer paper. Is the choice of a traditional Korean paper where you began for this painting? How does your choice of paper affect your subsequent drawing?

Moon: I use all types of paper, but I’m typically interested in mulberry papers, which originated in Asia. Within Asian countries, it’s very traditionally used to make prints and paintings, or even just for everyday uses. There are different versions in Japan and Vietnam, as well as Korea. In using this paper, I was thinking about how to make my practice more authentic. How to keep my identity in my studio practice. So I often use hanji, and even different types of hanji papers. They come in one layer, or even two, three, four layers. The qualities differ depending on what region of Korea they produce it in. It’s all part of my ongoing experimentation with different papers, and seeing how they work with my water-based media.

Guernica: Yes, and your completed works retain a fluid look as a result. Is your process very improvised? And how does revision look and work for you?

Moon: Of course, my studio practice is full of joyful and struggle moments. I do have some plans for the paintings in the beginning — knowing scale, a color theme, iconic images that I want to use — but most of the time I start very organically. I don’t have a fixed image that I plan to create. I keenly observe my process and incorporate or interrupt with my process to create paintings. I want to treat my paintings like a living thing that I collaborate with. I am always open to the possibility that my work will evolve and change. I let it happen that way. I feel I have more success when my process is more flexible and incorporates interrupting elements.

Sometimes I do have a few principles before I get started. For example, here, I decided that my main color would be yellow. But after that, I let the work be determined by the process.

Guernica: Even though the final waveforms appear very spontaneous, I noticed that they contain layers of strokes that outline and shade in the waves. Is this something you achieve by painting multiple layers?

Moon: Yes, there’s initially the big gesture, the mark-making that captures the moment. Then I go back and outline everything, to almost freeze that moment.

Guernica: And are there particular past artistic movements that you feel this mark-making process draws on?

Moon: With the big yellow wave, that spontaneous mark-making, I think about American abstract expressionism. You have to pour a color, to splash, to stain. That type of spontaneous mark-making.

At the same time, many people also mention to me Roy Lichtenstein’s brushstrokes from the ’60s. Lichtenstein also painted female figures with blue and blonde hair, and there are connections there to the Goldilocks myth. And many westerners see some of that in my paintings. In “Stranger Yellow,” I didn’t really look at those as references, but people often reference it. I find that really interesting. They call Asian people yellow, but then people look at my work and think of blonde beauty. There’s a little irony there.

Guernica: There’s also a contrast in your work between large, freeform brush strokes and miniature, detailed drawings — almost symbols — scattered throughout. What do you see as the function of adding in these smaller drawings?

Moon: Yes, at the same time as the large brushstrokes, I have floating iconography intersecting with the waves. There’s a flux of movements and things on the canvas. I hope that my iconographies can act like signs that almost guide you as you look at the painting, so you can go on to the next place.

One of the iconographies I’ve been using a lot is a peach. In Georgia, we have many peach trees. We have so many streets named for peaches. You see them represented on buses or in metro stops. So, living in the South for a long time, the peach became an important symbol for me. At the same time, the peach is an important Asian fruit that you often see in Asian manuscript paintings or folk art. It can be a symbol of chasing bad spirits away. So I use peaches a lot, and they carry these dual notions.

Guernica: You also include a lot of creature-like shapes among these iconographies. Where do these creatures come from?

Moon: I look at mythical creatures in different countries and try to combine them. For example, foo dogs are a popular thing people recognize from Chinese restaurants. In Korea, we have something similar called a haetae. It’s a mythical creature that sometimes looks like a dog, sometimes a tiger or lion or both. I’m really taken by it.

Guernica: I do notice a lot of hybridity in your iconography. With the creatures, for example, are you painting these directly from references? Or are you changing how they look as you paint them?

Moon: When people look at a cultural signifier, they have their own interpretation. Often, they get it wrong. It’s the same as when someone asks, “Are you Korean or Chinese or Japanese?” Often, they get it wrong. For me, this misunderstanding is often the first step of understanding. I use these cultural references and twist and change them into my own version. So you’ll see these animal shapes but you cannot easily recognize them. I choose and create iconography almost in a humorous way.

Guernica: There are some things I see in the painting that I’m not sure I’m interpreting correctly. Are there turtle shapes repeated throughout?

Moon: John Yau, the art critic, called them turtles too, but they aren’t actually. They are animal skins. I’ve seen it in Korean folk art and also in Indian art as well, when hunters catch large animals. Oftentimes in Korea, it’s tigers and tiger skins. They peel the skin as a trophy. Like, “Oh, I kept something really heroic.” I look to the shape to represent life and death, or something in between.

So originally, that image is from the tiger skin and how it’s depicted in folk art. But I have also interpreted it my own way and it has perhaps become something else. In “Stranger Yellow,” the tiger skins are cut from paper and then pasted onto the painting. I fold a paper in half, then cut, and when I open it again, both sides are exactly the same and the resulting shape is symmetrical. That paper folding and cutting technique is based on Mexican paper doll cutting. In their shamanistic rituals, they fold the paper and then, without drawing, they cut it all at once to create a paper doll. It’s a technique I’ve incorporated into multiple paintings.

Guernica: It’s fascinating how you’ve modified the visual of this animal skin by bringing in this other technique.

Moon: But I don’t mind people seeing the shape as a turtle. I always welcome different interpretations.

Guernica: I appreciate how you can take an initial iconography and pass it through multiple cultural lenses to arrive at an altered aesthetic. Where else do you feel this takes place in your painting?

Moon: There’s references to ceramics in this painting, and to patterns of blue and white. There is a western ceramic pattern called Blue Willow. If you google “Blue Willow,” you’ll see these beautiful Asian-influenced landscapes with a boat and trees. It’s a highly stylized pattern based on Asian love stories, invented by British companies. It’s similar to a fortune cookie, invented in California and being really an American thing rather than a Chinese thing. Blue Willow was like that for me. Westerners came up with this design thinking of exotic Asia, and I find that really interesting. On my end, I wanted to give it back to them. I used that pattern in my work on top of the yellow. There’s an irony there that I wanted to bring in, perhaps in a lighthearted way. But also, what I’m talking about isn’t just funny. It’s kind of serious.

Guernica: Yes, there’s this element in your work of layering historical references with more contemporary interpretations. It’s almost like a continuous revision of the past.

Moon: If you look at the way I use color combinations, I try to combine something old and something new. The base paper, which is slightly brown, references old books, antique furniture, and Asian antique objects. Then you have the super-bright candy sunshine colors from the acrylic, with very saturated layers of translucent or opaque shades of yellow. But overall, I’m more interested in current experiences. If I reference something from art history, it’s to honor our present time.

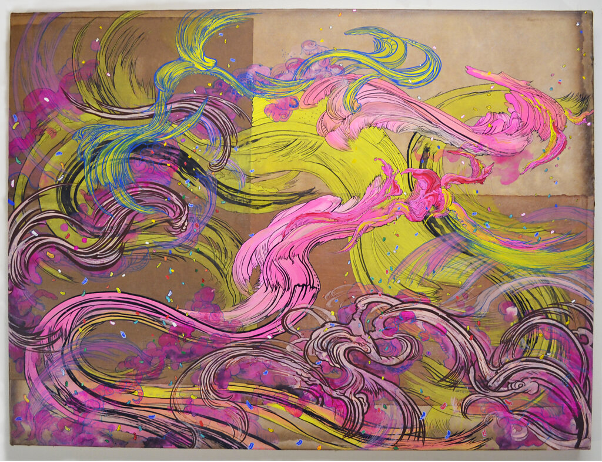

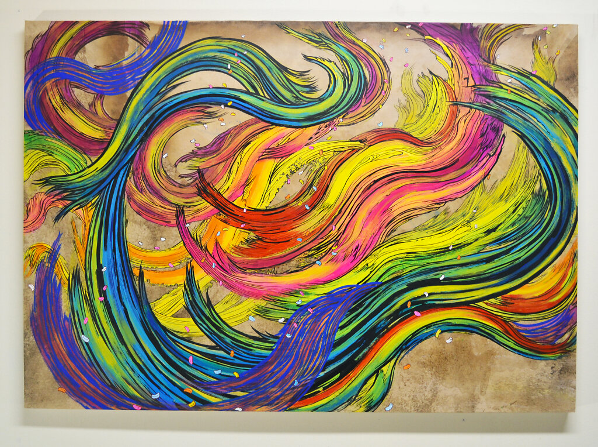

Guernica: You’ve started to mix in other colors in the paintings “Yellowave (Pink)” and “Yellowave (lgbtq)”. Can you talk about those works?

Moon: I was making “Yellowave (Pink)” when the Me Too movement was happening, under the Trump government. I watched the news and saw all these pink heads in Washington, DC, coming from all over the place to protest. It felt really overwhelming and exciting and angry at the same time. So in my studio, I was absorbing and reflecting. Pink, magenta, is not an easy color to use. When they used pink in the Me Too movement, they were almost using the color subversively, which I really loved. The LGBTQ painting was that way too. I was thinking about Korea, where we have a rainbow stripes color to celebrate children’s birthdays, parents’ birthdays, or weddings. It really elevates ideas of happiness and longevity. Here, that color also represents LGBTQ communities, and it’s a really interesting overlap. For me, color is the way I communicate or how I see what’s going on in the world. So that’s where these paintings are coming from.

Guernica: Do you have a particular perspective on the term “Asian American” or what that means in the context of these paintings?

Moon: I titled the show that “Yellowave (Stranger Yellow)” was originally in Stranger Yellow because oftentimes, even if we live in America, people see us as alien or stranger. With “Yellowave (Stranger Yellow),” the largest work created for the show, my mission was to make my kind of people beautiful and stand out. More visible. An adjective we sometimes hear is “the invisible Asian.” Meanwhile, Asian women are often used as objects in a very wrong way. I wanted to change that. I wanted us to be sunshine and beautiful and loud. Everything else goes along with that idea.

To read more interviews from our Back Draft archive, click here. The painting on the slider is an in-progress and completed version of Yellowave (“Stranger Yellow”), 2021. Ink and acrylic on Hanji mounted on canvas. 60 x 120 in. Images courtesy of Jiha Moon and Hua Xi.