Heather Christle’s poems are so wonderfully playful they can make you forget that they’re tackling the gravest of subjects. With short lines and seemingly simple language, she whisks you into the imagination’s darkest depths.

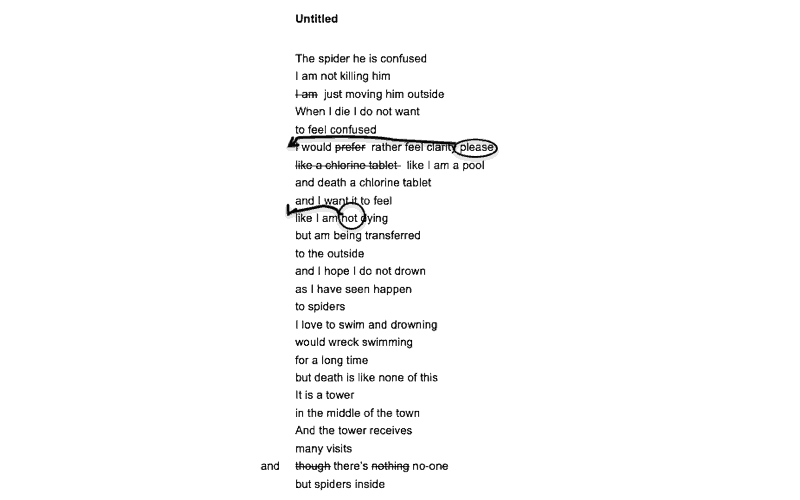

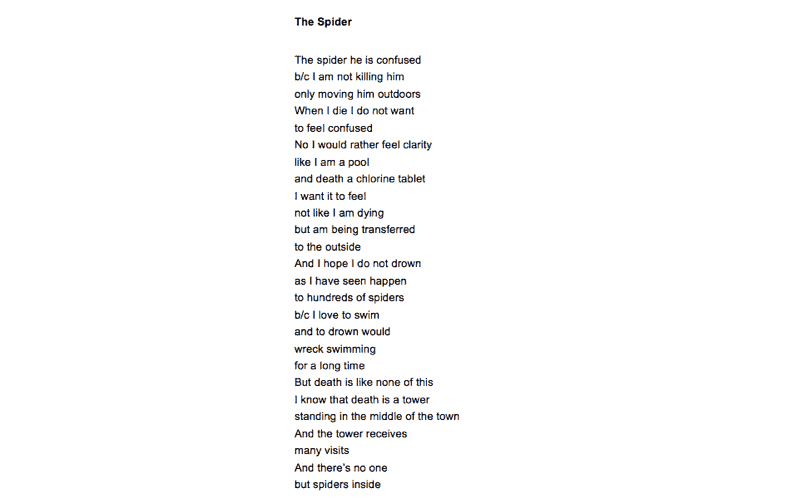

This poem, from her third collection, What Is Amazing, opens with a familiar scenario: confronting an unwelcome insect. It then leaps toward larger questions of life and death. While the two versions appear in type here, for legibility’s sake, Christle wrote the original draft by hand, as she almost always does. She explained to me that “the keyboard is not a house that [her] poems want to come to,” and that writing should feel like dancing.

– Ben Purkert for Guernica

Guernica: The changes between drafts are so minimal!

Heather Christle: I know. There’s a part of me that’s like, “Oh no, I don’t want to talk about revision, because I’m the world’s worst reviser.” But what I do usually, I write a lot. Like a poem every day. I work really quickly, and I revise as I’m writing. And then when it’s time to figure out how to put a book together, I do more revision then. But I’m far more likely to just let a poem be left behind than I am to try to shape it into something that wants to be public.

Guernica: That’s so interesting. For you, it’s not about laboring over each poem. You produce tons of them, trusting that a lot won’t see the light of day, which is its own kind of rigor.

Heather Christle: Yeah, yeah. I think it just works so differently for different people. Like my husband Chris, who’s a poet, he would work for years on things, and I kind of marvel at it, because it’s so different from my own experience. And he, I think, has a similar kind of marveling at the way that I do it. And I hope that there’s room for us all to kind of marvel whenever and however a poem happens.

With me, I can pretty quickly hear whether there is a thing that is alive inside the poem. But for me, if that thing that’s alive in some poems isn’t there, there’s nothing I can do to make it come forward, you know? Some poems have life, and some just don’t. Sometimes it’s an ostrich, and sometimes it’s a cinder block, and no matter what I do I can’t make a cinder block be an ostrich.

Guernica: And yet you do still revise, even if the changes aren’t necessarily huge. How does that work?

Heather Christle: It’s about listening to the rhythm of thought in the poem. In this one, it was all about slowing things down so that you could really hear the weird logic that emerges. In the early version, my words weren’t moving as slowly as the poem’s thoughts were. For instance, if you look at the line about the chlorine tablet, I was having these ideas at such a great pace that my first instinct was to write that I would prefer a chlorine tablet, and that got the basic idea down. But it was all wrong for thinking about tone and pace and thought. It needed to slow down to see the actual strangeness.

Guernica: It’s like you had to include the pool in which the chlorine tablet dissolves for the image to really land.

Heather Christle: Yes! Because the pool just isn’t present. Maybe I was doing a kind of shorthand for an image that sticks with me from Sylvia Plath’s “Tulips,” you know, where she talks about the dead closing their mouth on it like a communion tablet. Does she say tablet, or is it wafer? In any case, there was an intrinsic connection in my mind between death and tablet, but it had to be translated into the slowly developing image of the pool and the tablet, so that the clarifying actually happens in the poem, at the right speed.

Guernica: Your process is a lot about pace. In the first draft, you’re trying to get the words down as quickly as you can. But the computer’s faster, isn’t it? Yet you prefer to write by hand.

Heather Christle: For me, the keyboard is not a house that the poems want to come to. There’s also the fact that when you’re typing, you have all the letters before you on the keyboard, and you’re selecting from among a set of options, whereas when you’re writing, even though you may mostly be limited to a certain set of symbols, they have a kind of ability to have variation within them, and the em dashes can be weirdly different lengths, you know? I think there’s something that matters about the movement of my body and its ability to have a kind of dance that doesn’t happen when I’m typing. Like typing is not dancing, but writing is dancing.

Guernica: I love that. This is such a small detail, but it feels emblematic of something larger in your work… you changed “spiders” to “hundreds of spiders.” There’s a multiplying strangeness.

Heather Christle: Yeah. I mean, once you start to populate a poem with stuff, it does have a tendency to begin growing on its own. You’re looking at something else within the poem, and then you come back to it and there’s more.

Guernica: How would you describe your approach to poetry? The whole Allen Ginsberg First thought, best thought philosophy—does that resonate with you?

Heather Christle: I’m uneasy with the word “best.” I think that I know that the poems happen because I write them, but I also think that an enormous part of what I’m doing is listening, that I’m listening to the strangeness that is within us, and within our world, and within our ways of speaking to one another. And I’m listening to the energies and desires of the words themselves, which isn’t to say that I think that I’m actually listening to Martians, to borrow Jack Spicer’s metaphor, you know? I don’t think that I’m catching the voices of ghosts or something. I don’t know what is on the other side of what I’m listening to, but I do know that it, for me, has to be heard right away, that I can’t slowly revise my way towards it. If I missed it the first time, it’s not going to become present.

Guernica: But, if I understand your process correctly, you’re also crossing out words as you’re hurriedly writing those first drafts.

Heather Christle: Yeah.

Guernica: So, for you, writing and revision really aren’t separate stages?

Heather Christle: No, not really. That’s a great question. No, it all happens rapidly, really rapidly. It’s funny that you’re asking this, because I’m about to go spend a week in Massachusetts revising this book of prose that I’ve been writing for five years. I’m so ill-equipped to do it, because I have no training.

Guernica: This is a book about—this sounds so horribly reductive—but a book about crying, or your relationship to crying?

Heather Christle: Yeah. It’s a book about crying. That’s a totally legitimate description of the book. It’s a book of prose, and it looks at crying through all sorts of different lenses, and it also uses crying as a lens. It’s been a beast to work on. I finished a draft at the end of last year, and then sent it out to some people and got some suggestions, and then have not looked at it for like three or four months, as a way to give myself the ability to come back to it and feel stronger, more able to listen to what it might want to do.

Guernica: What’s pushing you to write prose?

Heather Christle: I don’t know. I didn’t mean to. I started with this idea of what would it be like to have a map of every place I’d ever cried, and then what would it be like to have a map of every place that everyone had ever cried? And then I thought I was just writing a little prose poem, and then I started to do a little bit of reading, and then I went back and wrote more, and it just kept growing. After I got through about ten pages, I was like, I think I’m writing a book, oh shit, I’m writing a book of prose, and then I lost five years of my life.

Guernica: In your Divedapper interview, you mentioned that you tend to think metaphorically most of the time. What it’s like to move through life that way?

Heather Christle: It’s dangerous. It can be fantastic to see the illumination of one thing in another, but it can be misleading as well. There are times when the metaphors that I’m thinking about aren’t coming from a strangeness but are coming from systems that take strict limits to the imagination. They might present themselves as acts of imagination, but they’re strict and limited. I’m trying to learn to see them for what they are. Writing this crying book has taught me, again, the joy of the connection between things, but also the danger of always seeing one thing in terms of another.

Guernica: It sounds like your answer is gesturing toward the political.

Heather Christle: Well, I think that metaphor and politics are deeply intertwined, and I think that the most dangerous metaphors are the ones that are invisible for us—the ones that people do constant political work to make visible. And I think that part of the work that I’ve been trying to do recently is to see where the imaginative life and the political life intersect, and how they might provide a way for us to live other than as we are.

To read more interviews from our Back Draft archive, click here.