Hangama Amiri is an Afghan Canadian artist whose fabric installations reflect and refract. Her life-sized tapestries, collected in “Bazaar, A Recollection of Home,” recreate apartment blocks and shopping districts in her home country of Afghanistan, reinvented and distorted through the lens of memory. Using a wide range of textiles in many textures, Amiri creates kaleidoscopic collages of vibrant and varied patterns, arranged in eye-catching compositions that invite meditations on the fragmentary nature of memory and on how we recreate our own pasts from pieces of the present.

Originally a painter, Amiri opts for a distinctively flattened composition that pulls different dimensions of space onto the same visual plane. In “Bazaar, A Recollection of Home,” places push up against each other, intersecting and overlapping. Every available space is filled with some design or motif, suggesting a crowded and many-layered relationship to the past. She excavates memories that are not only personal but engaged with how sociopolitical events have shaped her family’s history in Afghanistan.

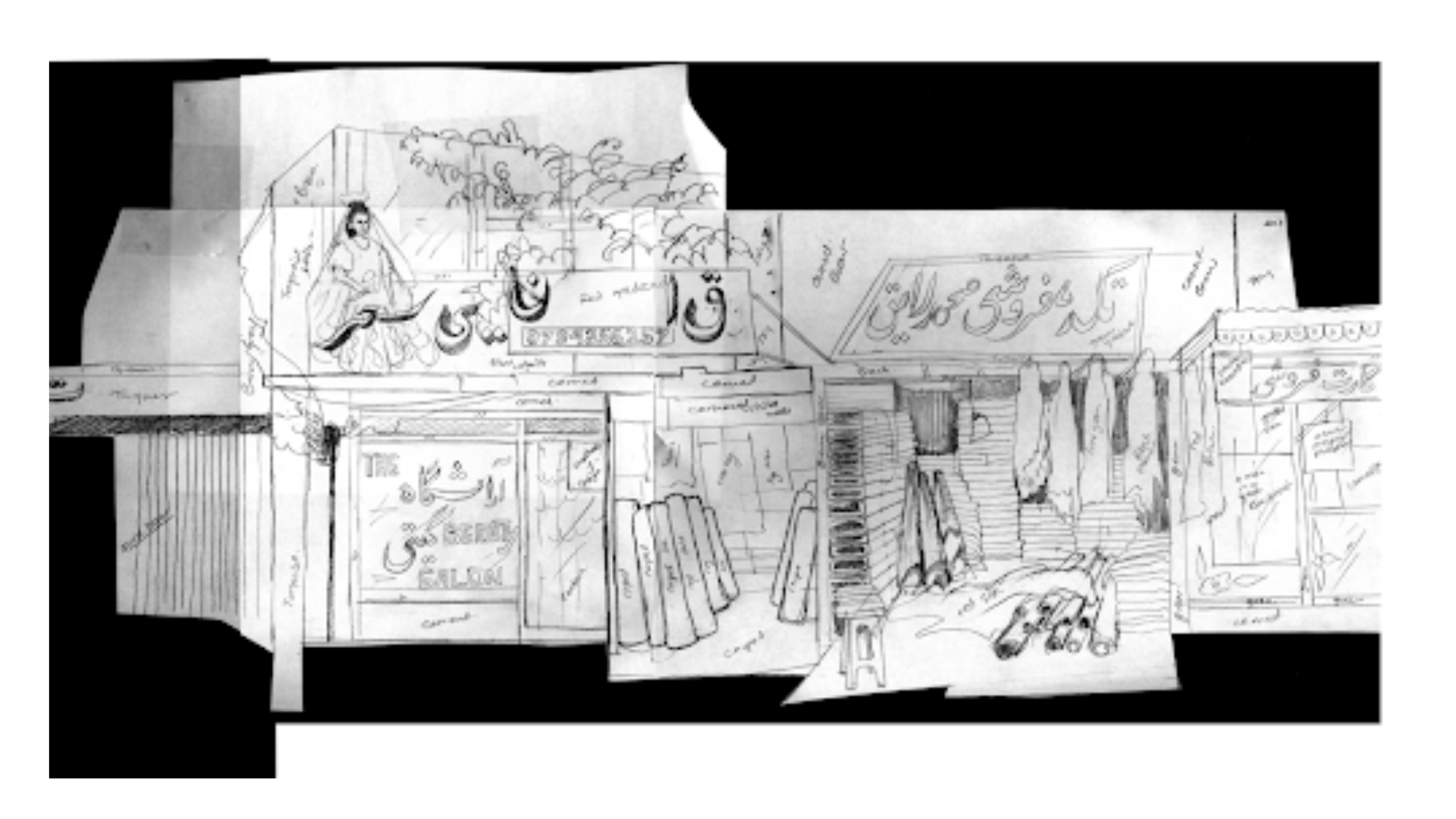

Amiri researches places she remembers from childhood, looking up photos online and collecting cultural artifacts. In this way, she revisits old memories and discovers new aspects of them. Her final pieces are both reflective of history and highly contemporary, hybrids of multiple eras. I spoke to Amiri about the central piece and largest in “Bazaar, A Recollection of Home” — a depiction of several connected shops titled “Bazaar” (pictured above).

–Hua Xi for Guernica

Guernica: Your final pieces involve a range of materials, but where do these visuals begin for you? Do they begin on paper?

Hangama Amiri: I start first with sketches, small drawings. I still have the drawing for “Bazaar” here with me on the wall. This piece came through a kind of understanding about collective memory, and these memories I had as a child of Afghanistan.

Textiles are very tactile. They’re very related to smell, to touch. They’re a very seductive material. So it really works when I incorporate personal memories, fragile memories, and connect them to the fabric’s qualities.

Guernica: Are there specific moments in memory that you are drawing on?

Amiri: “Bazaar, A Recollection of Home” is based on growing up around the bazaar environment. When I was in Afghanistan — between 1994 and 1996, before the Taliban came — we used to live in a very small neighborhood in Kabul, the Macroyan Kohna. It consisted of these building complexes built by Russians where a lot of middle-class Afghan families could afford to live, and these communities also had little markets and little bazaars. Growing up, we would go to the bazaar, and the memory of seeing the stores and the fabrics was my first inspiration for this piece.

One of my uncles was also a tailor, and I used to visit his shop in the mornings before school. Being in his shop, I was very inspired to see how people worked: seeing the scissors, seeing all these beautiful cotton fabrics that he’d receive from neighbors or from clients. So this idea of the community created by the bazaar really influenced me, and this idea of how a neighborhood comes together.

Guernica: Your works flatten and compress space in really interesting ways. Does that reflect your memories of the bazaar?

Amiri: A lot of bazaars are market environments. The shops are built on the street level of these buildings and they’re all side by side and they’re very cramped together but still have this narrow passage in between that people can walk through. I wanted to create a panoramic piece that suggested all these stores side by side, and that also gave you a bodily engagement with the world. Since this piece is also life-sized, it’s very immersive. When you walk up to it, you feel like you are in this fabric shop, seeing how the fabrics are hung.

Guernica: Does it take you a lot of sketches to arrive at the more finalized drawing that serves as a draft for the textile?

Amiri: It’s a lot of drawings. I’m interested in bodies of drawings, collections of drawings. I want to bring my thoughts and my memories onto the paper using pencil or colored pencil or whatever I can find. If I am not satisfied, then I do more drawing. Starting from those drawings, I edit. And in the editing process, I begin to research more and find histories and context for the images in my mind. Like where these images first came from.

I made this initial collage by cutting along the edges of the drawings. These were originally drawn on different papers. They’re really poor drawings too. But that’s how I do it. Sometimes they’re not perfect. The whole piece is like a fragment. I’m really interested in these imperfect edges that kind of reflect how memory works for me. These are fragments of experiences that I have.

Guernica: How does that research process add to or alter the images you originally had in your memory?

Amiri: Once I am focused on a certain past experience, I go about searching for images or visual languages in whatever form I can find online. Here, I also collected images online and images shared with me by friends and family. I had to expand my past experiences based on my more recent visits and other visuals, logos, banners, postcards, and commercial ads that I found.

Guernica: Your final textile also includes images within images, such as the section of the piece that depicts photos hanging in a photography store. Are those photos drawn from memory as well, or did you have references?

Amiri: In the photography store section of the textile, the images are from my own archival collections of magazines and postcards, especially Bollywood postcards. It’s like a mixtape sewn together.

During the pandemic, I opened my own stuff to see what I had. I hadn’t looked at the majority of these things in a long time. I wish I had been able to keep more things, but because of migrating to different countries as refugees, we didn’t have much space to carry things with us. We didn’t end up bringing a lot of stuff. I also buy items online. I look for items I remember and search for them and buy them, like with the Bollywood postcards. This searching becomes another way of engaging with these memories I have.

I also have some books, Farsi poetry books, or small images here and there that I use. They could also be from family albums we managed to keep — mine or my parents’. I sometimes go through those albums and try to find visuals that distract me or interest me. That’s another way for me to remember and give testimony to those diasporic experiences I grew up with. Bringing things but never owning them. That shapes my archival thinking.

Guernica: What was your process like when converting this drawing into the completed textile?

Amiri: So when I make these drawings and feel really strong about them, I project them onto larger pieces of brown paper, sometimes with an actual projector and sometimes by redrawing them in a larger size. That gives me an idea of scale. And it’s also an interesting meditative process, transferring the smaller scale to the larger scale.

From there, I use this technique of fabric appliqué. I cut the shapes out of the brown paper, then trace fabric from the cutouts to make the whole image. Then I join the fabric together to make the image. The process involves a lot of cutting and pinning and then sewing fabric together. For me, memory is a fabric, but in order to make it a whole, I have to put these fragments together.

Guernica: I see you’ve labeled the final drawing with different fabric names. How do you go about selecting the fabrics to use?

Amiri: In the original drawing of this piece, there wasn’t any color. For the majority of my drawings, I add color later and then, judging by the palette of the drawing, I choose my fabrics.

In this particular piece, I wanted to bring in fabrics that were used in Afghanistan. These fabric stores in Afghanistan have a lot of import and trade with neighboring countries like Pakistan, India, China, and Iran. So these stores have products from neighboring countries, and I wanted to bring those in as well. I used fabric from India and Pakistan — a particular hand embroidery, in polyester and silk. These are all things represented in that part of the world.

And I also hung a few fabrics that are actually from my own clothes that I kept. So a piece of my memory and body is also in that particular piece. It was another way of including my signature as an artist who loves fashion, color, and texture. It was a rather personal gesture to add to the work.

Guernica: That’s a beautiful idea. So within this piece, where might I see a fabric from Afghanistan?

Amiri: In “Bazaar: A Recollection of Home,” there is one piece called “Malalai Tailor Shop” that has an Afghan-handmade embroidery vest of a dress sewn in the left side of the piece. This particular embroidery is called Mirrors (Shisha) and is extensively used in traditional Afghan dress making. It’s a particular type of embroidery where the silvered mica or glass is attached to the fabric by means of stitched frameworks and encircling borders. The mirrors reflect the sunlight and also protect the wearer from negative energies and evil glances.

Guernica: Do you have a process for acquiring all these different fabrics?

Amiri: I go to fabric stores around New Haven and New York. In the New York Fashion District, there’s this specific store I usually go to. The owner is also from Afghanistan. He has a lot of varieties of fabrics, not only from the Western world but also from the Eastern and Asian world. There are ikat prints from Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. There are fabrics from Pakistan, where I have also lived. So I go to that store every few months to see what I can bring back to my studio.

I also collect fabrics from different countries myself. I order them online, which is also a way of being engaged with these different materials. And sometimes my friends bring fabrics to my door.

Guernica: Do you feel that your background as a painter influences the way you construct these visuals?

Amiri: Yeah. When I came to Yale to do my MFA, I came as a painter. In this piece, I painted onto fabric too. The female wearing a bright white dress — that’s all painted, very loose gestural mark-making. In Afghanistan, I would see a lot of graffiti and banners painted by local people. They often didn’t have much of an art background but they knew how to make an image, and I was interested in seeing how to reflect those images.

Guernica: You’ve also layered select bits of language onto this piece. What is the significance of that for you?

Amiri: Having the English as well as the Farsi is a way for me to engage my viewers. Language is another frontier for me, and I think about language a lot when making these pieces. Language comes through my experiences as a diasporic artist, as an Afghan Canadian artist. In my pieces, English and Farsi intermingle a lot. Sometimes they make sense, sometimes they are just abstractly playful. As you can see near the title, I just wanted to see some letters, as if they are being lost in between. That’s how I feel sometimes as well.

Guernica: So when you look at these final scenes, are they scenes of the past or of the present?

Amiri: They are definitely referencing the past but they are also very contemporary too. I am interested to see how the visuals of hybridity play out.

History always roots us. But we also have to find a way to speak about it, a way to bring things back and speak about them in a new light. In my pieces, I sometimes reference images from magazines from the ’60s and ’70s. It’s a way for me to engage my parents’ generation, by using vocabularies that my parents are familiar with. My generation is very different from my parents’ generation, with me being a postwar child. My experiences of being an Afghan are very different from my parents’ in Kabul in the ’70s and ’80s. That’s what interests me. I never had the world they lived in but I’m trying to find their visuals and bring them into my world.

Guernica: Do you feel that making these pieces revises your memories or how you remember?

Amiri: They don’t necessarily change my memories but they do invent new things for me. This particular bazaar piece, it made my world closer to being this child again, to this happy memory of childhood, even though what happened after was very sad. By choosing these colorful fabrics, I could focus on the festive, happy side. Even the act of drawing the initial sketch but not coloring it in and then choosing the colors and piecing together the fabrics — that is a process of invention in itself. It’s not necessarily about what I want the memories to do, but about what they do to my work.

My goal is to find a way to talk about these memories. When I choose a photo, I know it’s not the exact image but the culture and colors I was familiar with. It’s also a way for me to engage with my other millennial, diasporic Afghan people. It might bring them into an engaging conversation. I’m trying to rebuild this history and find a way to engage with all these people again. We’ve been literally dispersed. These visual bodies of work are also a way of gathering these diasporic experiences back.

To read more interviews from our Back Draft archive, click here.