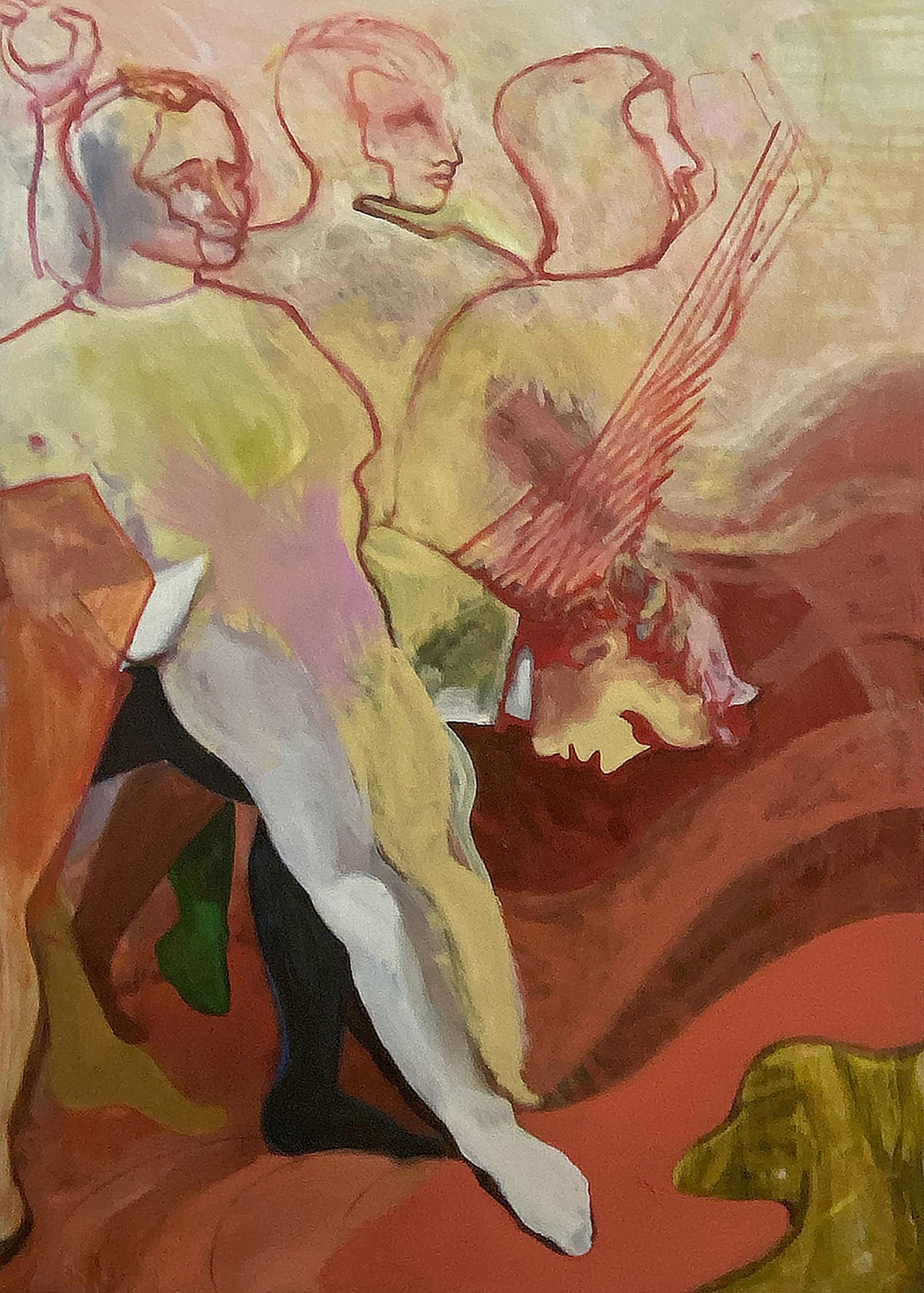

Artist Emma McMillan unearths the subjects for her paintings in archives. Reaching into the halls of the past, she uses her brush to achieve a kind of conversion, breathing new life into forgotten narratives.

This spring, the Bronx-based painter turned her attention to the Paul Rudolph Foundation, where she fell in love with one of the late architect’s murals. Depicting the biblical story of Susanna and the Elders, the mural was commissioned for another architect’s townhouse, though its whereabouts are currently unknown. What led to its disappearance, and what was the mural doing in that house to begin with? McMillan decided to create her own rendition. Then COVID-19 struck. Returning to her canvas months later, after a long battle with the virus, the painter made dramatic changes to her work-in-progress. When I spoke with her, she talked about the comfort she found in the Bible, Caravaggio and queerness, and what can happen when things get to spend more time in the drawer.

— Kat Herriman for Guernica

Guernica: How did you first connect with the Paul Rudolph Foundation?

Emma McMillan: My friend Eduardo Alfonzo was hired as a curator and education director there. He was given the task of examining these very extensive archives. Over a couple of years, he took that material and turned it into a roving exhibition that traveled to Rudolph’s different offices. Once they’d set up the education center in New York, he invited me in to do an interpretation.

Guernica: And how did you land on this artwork depicting the story of Susanna specifically?

McMillan: It’s from a townhouse on 63rd street that was built for a prominent gay architecture and urban planning couple in pre-Stonewall New York. I landed on this project because it encapsulated Rudolph’s desire to destroy the idea of the traditional family unit. Historically the townhouse is a home for the atomic family. And yet this was a townhouse created for two lovers who were really living outside the law and not bound by a conventional family structure. The interior of their house is made of glass walls and all the pipes are visible. Even the sinks are transparent. So, on the one hand, you have this pure acid utopia and on the other, this extreme orthodoxy of the biblical story. I was interested by that contradiction.

Guernica: You mentioned to me before that you think Rudolph’s selection of this particular story was a kind of personal jab.

McMillan: Yes. He’s trolling them. He was publicly out at the time while his clients remained closeted. There was tension between them and you can see that in this extremely Christian gesture anchoring an otherwise unconventional space. I think it’s either Rudolph’s critique of the couple’s willing embrace of a failed heteronormative norm or a way to point out a kind of infidelity to their queerness.

Guernica: You backed this theory by saying that the couple seemed to go to great lengths to cover it up.

McMillan: It’s clear they didn’t like it. In all the archival photos, they positioned an African male fertility sculpture in front of the lens obscuring the mural. Today its location is still unknown. It’s as if they just built a wall over it.

Guernica: When you were making your version, did you model it after Rudolph’s?

McMillan: I was looking at both Rudolph’s version and Domenico di Michelino’s wedding chest that he based his on. Of course, the feminine falls mysteriously outside of both of these interpretations, so I was left with this wild abstraction that is Susanna. To pursue her, I had to get away from big figurative conventions.

For me, I’m really interested in the borderless body of a woman or the boundaryless family that Rudolph was imagining. It’s about taking the orthodoxy out of both of interpretations by relieving them of their allegorical, human restraints.

Guernica: Speaking of the body, you started these paintings and then were abruptly interrupted by your own. You became very ill and had to take two months away.

McMillan: Yes, I got pretty far down the path and then was interrupted by COVID. Coming back I realized that the thing that was missing was the same thing that had been missing in all the versions that came before: the woman. So I started to work in reverse and destroy what I did before.

Guernica: And you mean that literally because, when you returned to the studio, you started sandpapering your own work.

McMillan: It’s a technique I’ve used before called frottage. I find in going back through previous versions of a painting you arrive at the instinct. When you are destroying the surface of a painting you are also getting something in return. I also love the idea of defacement and getting the chance to do it to your own work.

Guernica: How do you know where to dig?

McMillan: It’s like being an archeologist. You can dig and find that old contour or that spot of light that’s buried beneath it. It’s a weird inverted version of chiaroscuro. It helps to think of painting as additive or subtractive. The history of Western painting is all additive and then Caravaggio comes along and inverts it, working with these principles of seen light. Chiaroscuro is a queering of all the art that came before it, which is why he is the most mind-blowing artist of all time and also why I often work with this oppositional theory of color. It produces the wackiest and most compelling results.

Guernica: You told me you wanted this series to be kind of decorative. Can you explain?

McMillan: There is a decorative painting tradition demonstrated in the Rudolph and the Michelino. The Michelino is basically a jewelry box, and Rudolph sits in this tradition of decorative mid-century painting where architects would make these kinds of zombie ornamental paintings. It’s such a cool, under-appreciated genre—painting that responds to the interior of a home is something that is so lost to us today. Everything is made a la carte to be shown at art fairs.

Guernica: Calling someone’s painting decorative is almost an insult.

McMillan: In art school, it was the nastiest thing you could say. I think that’s so delicious. It’s a total fuck you to Modernism’s claim that everything has to have a function. It’s like, nope, this is just here to be glamorous and contribute to the environment. It goes back to the strangeness of Rudolph taking a biblical convention and transforming it into decor for this psychedelic house. There is something insouciant about that kind of decoration, almost like the haunted doll in the closet. It’s a tell-tale heart!

Guernica: How will you know when your series is done?

McMillan: There is a hiding and revealing game that I’m always playing with painting. Completeness for me is about reaching a point where I’m both showing and taking enough.

You once asked me: Is painting like writing in that there is an obvious place on the page where you left off? I said yes at the time, but now I think the answer is no. It’s easy to lose yourself because painting is fundamentally about revealing and hiding. I got completely lost walking away for two months and I found myself in a completely new place when I returned. Part of that was that I started reading the Bible and I found it very comforting.

Guernica: What was comforting about it?

McMillan: I grew up with the Bible and I think a lot of what I do springs from the infinitely open possibilities of literature. The Bible is the most familiar piece of literature to me; I started reading it when I was seven. I’ve had this obsessive relationship with the Bible since I got sick. At first, I was receiving all these messages of hope in Psalms and Corinthians, but now it’s more twisted, and it’s become about what it’s like to live in the end of times. It’s really a text you can live in. You could also live in Marquis de Sade, and some people do.

It all started because the friend I’m in love with told me he was reading the Bible. I told him I was going to read his Song of Solomon which is some epic Greek love poetry. Rereading it was so devastating. It was still early on in the pandemic. The poem hit really hard, and then it led to other passages like a section from Corinthians that’s then explained in John. All the lights went on in my brain again.

Guernica: Do you see the biblical story of Susanna as romantic?

McMillan: Yes, it’s about romance, but also about fracture because there is this violent gesture, the stoning of the elders that has to happen for this woman to demonstrate her fidelity, and what is more romantic than that? It’s romantic in the nineteenth-century way in that there has to be divine sublimation in order to bring two people together.

Guernica: How did you seek to express Susanna’s autonomy in your paintings?

McMillan: Through monstrousness and victimhood. I distilled it down to this external conflict between order and chaos, essentially. Painting is first and foremost a psychological medium, and it makes sense that the farther you stray from allegory and figuration, the further you end up in the wilds of abstraction. These paintings wander in both directions.

To read more interviews from our Back Draft archive, click here.