Navigating the world isn’t always easy. Poets can’t help smooth the path, but they can—at the very least—shine a guiding light. Recipient of the MacArthur Genius award and countless honors from the academy, Edward Hirsch writes poems that illuminate the everyday dangers that await us. He often situates his speaker in treacherous circumstances, whether physically or ethically, and dares them to find their own way out.

When I chatted with Hirsch via cell phone, his thundering Chicago accent came through loud and clear. He explained why nighttime is most inspiring to poets, how he sees the relationship between interiority and political engagement, and what Russian and Polish poets have to teach us about “the quest for social justice.”

– Ben Purkert for Guernica

Guernica: What was the genesis of this poem?

Edward Hirsch: I was writing a group of short-line poems that were all one sentence long. And when I was writing these poems, I kept being attacked by memories. And the poems, the memories, were sort of flying at me and I was trying to write them down and figure out how to get them on the page.

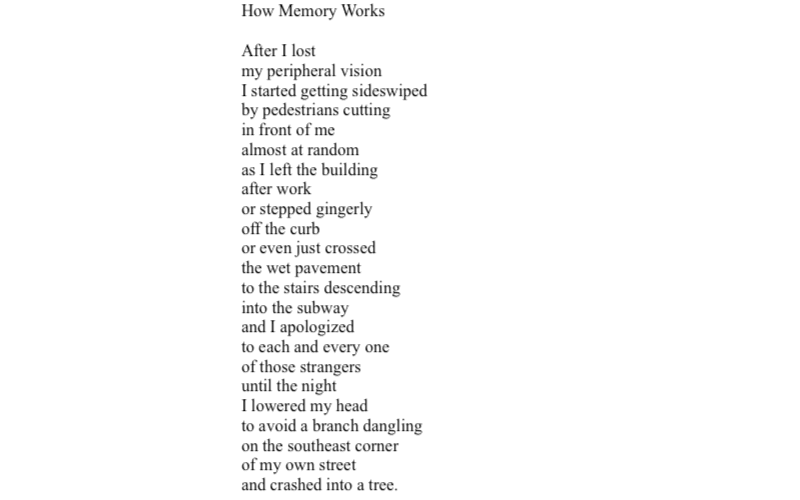

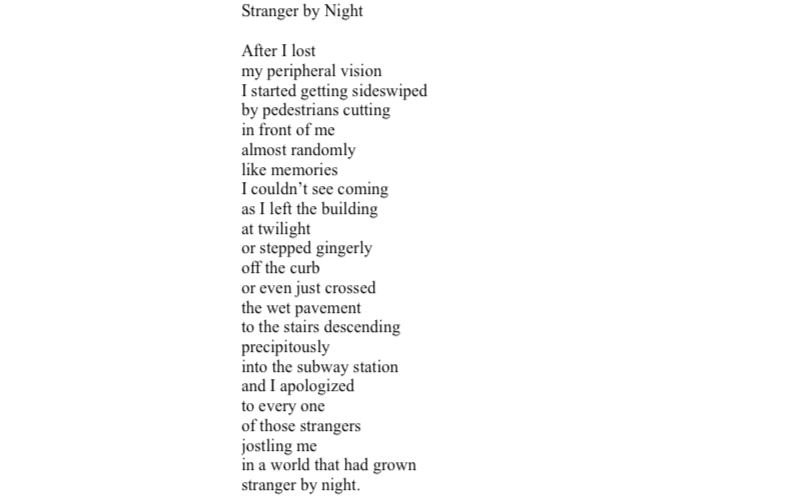

And, at the same time, I’d lost my peripheral vision—I have an eye disease—and now my walks at night are suddenly much stranger than they used to be. And so, when I’m taking a simple walk, like Grand Central to Times Square—which I do most nights—suddenly, at rush hour, people are bumping into me and I’m bumping into them because I don’t see them coming from the side. Originally I thought this was a poem about memory, and that’s how I wrote it. Then, when revising, I moved away from the “How Memory Works” version. I felt the title was too editorial.

Guernica: What do you mean by that?

Edward Hirsch: By calling it “How Memory Works,” I felt the whole poem became a metaphor for memory. That’s what I mean by editorial: the poem turned into a commentary on the drama, and it was more interesting to me as a kind of drama in itself. The central subject needed to be the walk and how a walk can become suddenly estranged and the world itself grows stranger.

Guernica: One other revision really stood out to me: in the early version, the speaker ends up crashing into a tree.

Edward Hirsch: Ha! Yes.

Guernica: It seemed almost slapstick to me. Whereas the revised ending has more gravitas, more expansiveness.

Edward Hirsch: That’s what I was hoping for. I never liked how, in the early draft, the poem came crashing to a halt. I wanted it to open out into the mystery of night.

Guernica: Re-reading The Living Fire: New and Selected Poems, I’m struck by how many of your poems take place after sundown. Why is that?

Edward Hirsch: I’ve always liked the dramatic situation that finds a speaker alone at night. It creates the feeling of a solo consciousness. By which I mean, someone engaged in poetic thinking versus ordinary thinking.

Guernica: What’s the difference?

Edward Hirsch: Well, it’s what I would call daylight or common sensical knowledge versus associative reasoning, or reverie or night logic. In the evening, the mind has much more space to roam freely.

Guernica: How did you arrive at this idea?

Edward Hirsch: For much of my life, I was a terrible insomniac. And when I was young, I did a lot of my writing at night. But it also comes from my reading. I discovered that a lot of epiphanic poems take place at night, often at the hour of midnight. The gong is always striking midnight in Yeatsian poems. Baudelaire has a poem called “At One O’clock in the Morning.” But it doesn’t only have to be night, strictly speaking. In Wordsworth’s “The Prelude,” whenever the sun is blotted out and he steps into a cave or he’s under a tree, the repression of light often leads to what he calls “visionary gleam.” It’s very much related to the tradition of the dark night of the soul, where the hour of 3 a.m. or 4 a.m. becomes a kind of externalization of a lost interior state.

Guernica: And even though you no longer write at night, you’re still tapping into that sprit.

Edward Hirsch: Yes. I now mostly write in the early mornings. But, you know, there’s that space between the time in which you’re writing a poem, and the time in which the poem is taking place. So, for example, you start a poem that you’re setting at dusk, but then you write it one evening, and then you add to it another day; and over a course of three weeks or a month, you’re writing a poem in a lot of different time periods, but the poem is still set at dusk. So, when you write it, it’s not exactly the same as the dramatic situation that you’re setting up in a poem.

Guernica: Since you mentioned Wordsworth earlier, it reminds me a little of his assertion that poetry “takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility.” As if it’s necessary for some time to pass.

Edward Hirsch: Yes. And you’re not just writing inside of your own experience because you’re also trying to dramatize the experience for the reader. For someone who doesn’t know you at all. And then, in other cases, you’re writing out of a persona that’s very clearly not yourself. But in my more recent poems, and certainly in “Stranger by Night,” it’s not a persona. The speaker in the poem is a version of myself.

Guernica: How do you conceive of the reader? Your poem leans on that word “stranger”—is that who the reader is for you, or someone more familiar?

Edward Hirsch: Every poet imagines his or her reader in a different way, and many people try never to think about the reader at all. I imagine my reader as someone who doesn’t know anything about me. And I don’t assume that the reader and I are pals; I don’t assume that the reader’s read anything by me in the past. The oddity of reading poetry is that there is a remarkable intimacy established between two people who do not know each other, who are physically removed from each other by space and by time. And this, somehow, enables a kind of connection that’s difficult to establish in ordinary social life. So, yes, I imagine the reader as a stranger.

Guernica: Is the reader still a stranger by poem’s end? Or is this part of what a poem strives to accomplish, a transformation of that relationship?

Edward Hirsch: That certainly happens when I’m reading poems. When I’m reading poems that matter to me, I feel that I really know something about the person who wrote it that I didn’t know before. And I don’t know if you ever have this experience, but when I was young, I didn’t really know any poets. And, later, when I began to meet them, I felt the weird disconnect that you sometimes feel between reading someone and then meeting them. Later, you begin to put together how those two work together. But, at first, the way you know someone through their poems is so deep and intense that you really know something about someone’s interior life.

But there are also a lot of things you don’t know about them, in terms of their ordinary social behaviors. And there’s always a bit of a gap between the actual person who turns up in front of you and the poems that he or she writes. As you get to know the person better, you see the connection. But I believe wholeheartedly in the act of reading, and the connection that’s established between a reader and a poet seems very deep and intense. So, by the end of reading someone, you’re deeply familiar with them.

Guernica: How does that conception of the reader affect your revision process?

Edward Hirsch: I think it compels me to try and make things clearer. If something is important to me and I want to include it in the poem, I can’t assume that the reader already knows anything about it.

Again, not all poets feel this way, though. Some poets write a poem, and if someone has some random theory about it, or it means something completely different than what they intended, that doesn’t bother them. I don’t feel that way. I prefer it when readers take something from a poem related to something I put into it.

Guernica: In addition to being a poet, you’re also a scholar of poetry, particularly the Eastern European traditions; has that informed your thinking about the relationship between poems and meaning?

Edward Hirsch: When I first started reading the Eastern Europeans, I was looking for an alternative to Anglo-American modernism—which was smart, but very cold. And when I found the Russian poets of the ‘20s and the Polish poets of the ‘30s and ‘40s, I found a poetry of high intellection that was also more passionate. And that combo of passion and intellect really sang to me. It was a welcome departure from Eliot and Pound.

I also came to discover a kind of conversation in this poetry between what [Adam] Zagajewski calls solidarity and solitude; and a kind of dialogue between interior life and the quest for beauty; and metaphysical questions and social historical issues. And that these poetries engage in a conversation that balances the rights of the individual and the obligations of the society. And the poetry positions itself between these two extremes. This seemed like a nuanced response to the question of whether poetry should be engaged in the quest for social justice, which is one of the crucial questions for poetry in our time.

Guernica: Where do you stand on that?

Edward Hirsch: Right now, it seems like the American consensus is that all poetry should be about social justice—or, most people seem to think so. And I understand the pull towards social justice and poetry. But I also think that poetry is about a lot of other things, too. Personally, I’m more interested in a kind of conversation between interiority and engagement, rather than a poetry committed to one or the other.

Guernica: It sounds like you’re saying it’s a false choice.

Edward Hirsch: But I don’t think it’s a false choice for all poets. You take someone like, say, Pablo Neruda, and he was very clear that poetry should be socially engaged. You take a poet like Muriel Rukeyser; she is deeply committed socially, and I respect that. And then, you take a poet like, say, James Merrill, who didn’t believe that poets should ever read the newspaper. Or the most extreme version of this would be someone like Mallarmé, who believed in a poetry divorced from the world.

An interesting case on this subject is George Oppen, because George decided that he was an activist as a person, but he didn’t think poetry should be activist. So, when he moved to Mexico as a communist and a social activist, he stopped writing poetry. And then, when he did write poetry again, it was not political; it was philosophical, a kind of interrogation of existential and metaphysical issues.

Guernica: Can we turn to the personal for a moment? I’m very sorry to hear about your eye disease. How has it been to lose your peripheral vision, and how has it impacted your poetry, if at all?

Edward Hirsch: My descriptive powers as a poet have changed, certainly. But I can’t say how exactly. Like everything in life, it’s a process. The poems evolve.

When I was revising this poem, and I’m talking about deep revision, not simply the lineation or the form, but really thinking about its subject, I realized that the visual of me apologizing to strangers had to be the focal point. In other words, through the lens of this poem, I hope that apology takes on greater weight.

Guernica: “Stranger by Night” is the titular poem of your new collection, due out from Knopf in 2020. Is it representative of the others in the book? Are all the poems striving toward a similar kind of strangeness?

Edward Hirsch: At this stage in my career, I’m not looking for a poem that is completely clear and leaves the world a more comprehensible place. I’m looking for a poem where the surface is clear, so you don’t have to guess what’s happening, but it deepens your experience in the world, which actually becomes stranger and more mysterious over time, rather than more familiar. In other words, I want total clarity in the dramatic situation of the poem, but a deeper sense of mystery in terms of what it reveals about the world. That’s the aspiration, at least.

Guernica: As I reflect on your earlier comments about politics and poetry, it strikes me that “Stranger by Night” is not a poem devoid of political resonance. It presents a speaker who is visually impaired and must navigate public spaces, coming into violent contact with others who don’t make room for him. How such a speaker engages with the world isn’t an apolitical question, it seems to me.

Edward Hirsch: I agree. I’m also struck, talking to you, by how urban this poem is. It’s really a city poem, about feeling like you’re continually up against other people, literally. How you navigate that challenge and how you relate to other people is very much a democratic question of how we choose to live. And we all know about the breakdown of civility that can happen in cities.

Guernica: Having lived in both, do you see this breakdown happening more often in New York or Chicago?

Edward Hirsch: All cities. But more New York.

“Stranger by Night” originally appeared in The Threepenny Review.

To read more interviews from our Back Draft archive, click here.