Some poems present entire worlds; others take the form of fragments. With sharp edges and cinematic styling, Cynthia Cruz’s poetry focuses our attention on a visually arresting aftermath: the pieces—and people—that no longer fit neatly into the whole. Each line seems a clue to solving a greater mystery.

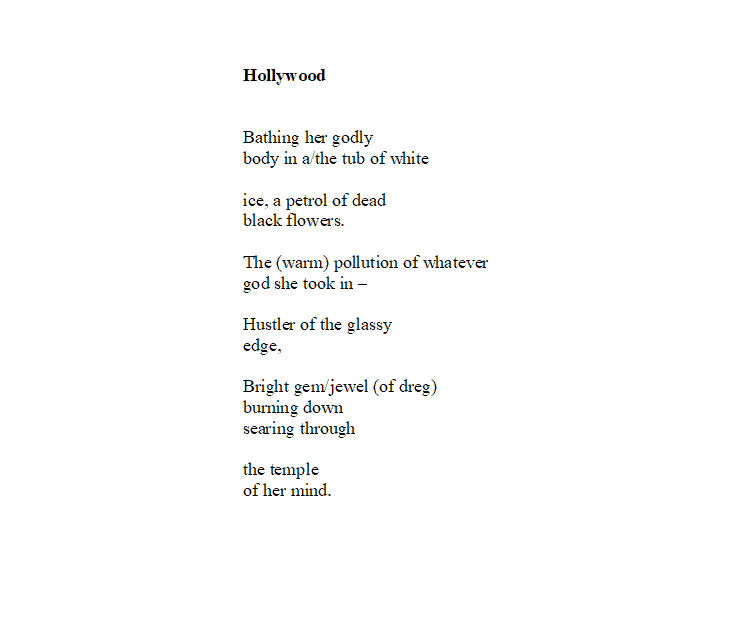

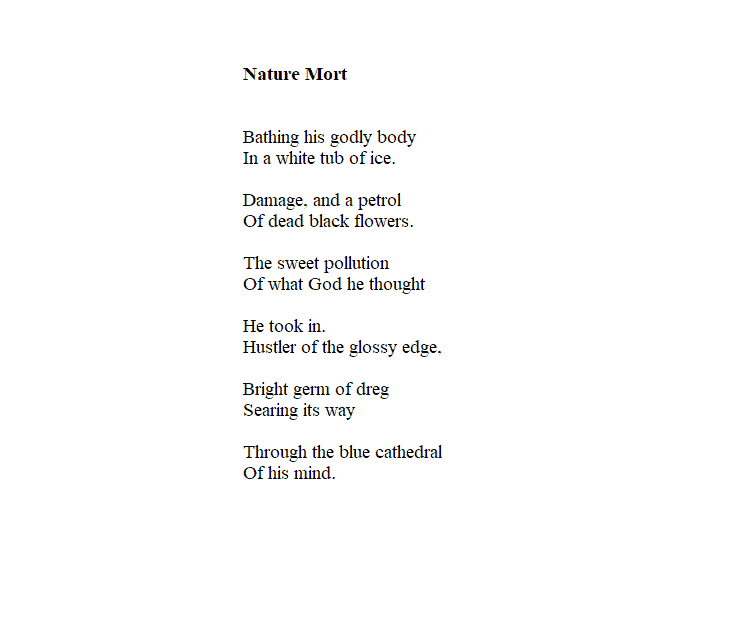

This poem, from her forthcoming Dregs, features a bath scene turned sinister. I asked Cruz about the process of its composition, but our conversation quickly moved beyond it, from painter David Salle to poverty in America to anorexia-as-metaphor.

—Ben Purkert for Guernica

Guernica: This poem, like much of your earlier work, uses a short line. Does that put more pressure on revision? Is each choice more scrutinized?

Cynthia Cruz: Well, I keep telling people that I’m not the poet I used to be, that I’m not going for perfection and the crystalline poem and crystalline line, but, in some ways, maybe I still am. I feel like each line can be its own universe and own poem, and each stanza too. I’m also very precise about the last word of each line, so I’m using enjambment intentionally and trying to tutor the reader to slow down.

Guernica: I’m curious about the shift in gender from she to he. What prompted it?

Cruz: I think originally the embodiment felt like the character was female. Then, as I revised, the poem wanted to switch to this other gender. The character arrived in my mind and then changed, if that makes sense. It doesn’t really, but it’s the truth.

Guernica: Do you often think about character when writing poems?

Cruz: It’s funny, I don’t really. I feel like I’m very fortunate because, by nature, I’m an introverted, shy person and when I meet with people afterwards, I think, Oh, my God, I shouldn’t have said that, but for some reason, I don’t have that about writing. And so, no, I don’t think about what I’m going to write or about character or form or anything like that. It just comes.

In some of my earlier books, the characters are sort of these ghosts of people I’ve known or people who were actually in my life. They become a symbol of who they are. I don’t want them to actually be who they are anymore.

Guernica: In one interview I read, you talk about how you want each book of poems to be different than the one before. Does this inform how you revise?

Cruz: You know, I honestly feel like it’s just organic. I’m a different person now than I was, say, in grad school. When I went to grad school, I was so excited. I was voracious. I read it all. I went to all the readings in New York. Then I started getting interested in the visual arts, and I married an artist. So that starts to show up in the poems. More references to artists and things like that. Then, more recently, I’ve been writing essays about political philosophy. And those themes may not show up literally, but they’re in there. As I change, the work changes.

Guernica: Right.

Cruz: And craft is a big part of this.

Guernica: How so?

Cruz: Without craft, I can’t build anything. I was once in an art-writing class with David Salle, and he said something like: An artwork is like when you go to a party and you meet somebody and you immediately like them or you don’t like them. It’s true, right? If the artwork is really good, if the artist put everything into it and crafted it the way that they imagined, it’s going to be representative of the artist.

Guernica: You’ve talked in the past about your upbringing. How does that show up in your poetry, if at all?

Cruz: Well, I’m from a working-class family in California, the first of my family to go to college. Then I got a bunch of degrees, and now I teach at some of these places. So I’m in this kind of in-between place. In my first couple of books, when I look at them now, I can see that those were poems written by a working-class American poet, clearly. Not by the process or anything but by the things that are in them. You have truck stops and, well, that’s a cliché, but you have the description of the actual world. And that’s something I feel strongly about, that when we place objects from the culture into our poems, it reminds me that we live in this world. Because the world is happening, right? I mean, I live on a street. There are people here. There’s the president. They’re not giving press conferences lately. These things are actually happening, and they affect me as an American citizen.

Guernica: I remember reading about how your family didn’t have much money, but would save up to go to the ballet or the occasional summer trip to Europe. It seems like your poems are rooted in multiple realities, in a sense.

Cruz: Exactly. And the other thing I would add is that I’m an adjunct. I make very little money. I’ll just leave it at that. My partner has a disability and relies on SSDI, and we are always concerned about whether these things are going to be revoked, what’s going to happen. So even though I teach at these places and I’m involved in all these high cultural things, that’s the reality, that’s the world that I live in. Yes, I know about Eastern European art, but still. I guess I could just write beautiful poems if I wanted to, and there is a place for that, too, because that would be an escape. But I feel like it’s important to leave an imprint or an archive of work that’s indicative of the way things are right now. Of course, no matter what you write, it will be indicative of it, in some way. I just don’t hear or see people writing about poverty or SSDI or food stamps or WIC or anything like that. And that’s a reality for most Americans. At the same time, I don’t think about this stuff when I’m writing. I just write. So the thing I’ve been having my students do is keep a composition book and archive everything from their life with the idea that all of that belongs in the poem.

Guernica: How does that material then get shaped?

Cruz: So they’ll bring in a poem, presumably an early draft, and we focus specifically on the poem. It’s no longer about the archive or the journal or any of these things that we’re talking about. That’s just the process of collecting the stuff. The real work is deciding what’s going to make that one poem the strongest poem it can be. I see it like each poem is its own little animal. And you want to figure out: What is that animal? What is the shape of it? What’s the tone and the sound?

Guernica: Can you tell me more about your forthcoming book, Dregs? Is this poem indicative of some overall theme?

Cruz: In terms of the book as a whole, I rarely have a concept before I begin. Except for Wunderkammer, maybe. But usually the books are a collection of poems that took place over a period of time. In this case, I knew I wanted to write about this idea of dregs and poverty. This idea of remnants or excess and what stuff gets left, what people get left out.

Guernica: In your interview with The Rumpus, you liken revision to anorexia (“a kind of compulsive repetition and deletion of parts of the self”). Can you elaborate?

Cruz: In the early years, I would do forty-something drafts. It was all about aiming for perfection. Then, a few years ago, I realized that that wasn’t exactly the aesthetic I was aiming for, and what I’m trying to say can’t be said in that kind of lineation and that kind of a poem. So I would say that that kind of very almost violent editing, which is where I come from, where my training comes from, it’s very anorexic, right? It’s aiming for this perfect, crystalline thing.

Guernica: Comparing revision to anorexia… I’ll admit that it makes me a little uncomfortable. Or that it troubles me a bit?

Cruz: How does it trouble you?

Guernica: Well, I recognize that art-making isn’t necessarily a healthy practice—Anne Carson has that great line about how art isn’t therapy—but I do find it unsettling to think that revision could be seen as something so self-destructive.

Cruz: Oh, right, right. So anorexia is complicated. When I was really bad in high school, I would cut a protein bar into pieces, and eat each piece. But I haven’t done that for decades, right? That kind of control—and it’s control over the body and control over one’s world—that, to me, is very similar to this kind of super, super, super control over the poem. That’s the way I used to revise. I went to grad school thinking, I don’t know anything, any of this stuff. Everyone who is a poet heard poetry when they were, like, four, so I felt way behind, and felt a lot of shame. I would go to workshops, and people said, “We don’t know what you’re talking about.” That’s truly what they said.

Guernica: Wow. That’s horrible.

Cruz: I felt like crap. I didn’t quit, but there was a real sense that I needed to become something else in order to be a good poet. It’s not a clear distinction, but when I was cutting up the protein bar in high school, it was an idea that if I could just control my life, things would be okay. If I could just write the perfect poem—same thing. But like I said, that’s not how I think anymore. So I do revise, just like I do eat, and it’s fun for me. And the way that I make a poem isn’t so controlling, right? I don’t go through forty drafts anymore. It’s more like a collage or something. I just make this thing, and then I revise it. It’s very natural. I’m not saying that revision is like anorexia, but simply that for me, the way I used to revise and editing chunks out of a draft felt similar. It was about cutting myself down to a small size and not taking up space.

Guernica: Right, right.

Cruz: The other thing I think about, which is loosely related, is what the difference is between someone liking my poems and someone recognizing that they’re good. I think we get really confused about that. I don’t have to like everyone’s poems, but I can recognize when something is crafted well. That’s what I’m aiming for. Anyway, revision takes a long time to figure out. It’s a balance.

To read more interviews from our Back Draft archive, click here.