How should one speak of the dead? In hushed tones or a more boisterous register? In either case, the deceased insist on remaining present in our lives. “The past,” writes Emily Dickinson, “is not a package one can lay away.”

Poet and visual artist Bianca Stone finds inspiration in that past. In her poetry, most recently her collection The Mobius Strip Club of Grief, she imagines a world in which poets like Dickinson find empowerment through tragic-comic stage performance. Off the page, Stone works to keep the legacy of her grandmother Ruth alive. Established in 2013, the Ruth Stone House is a gathering space that supports poetry and the creative arts, in accordance with the former Vermont Poet Laureate’s wishes.

When I invited Stone for this interview, she asked if I wanted to discuss her poems or Ruth’s. Both, I replied. We could start with her poetry, then work our way back.

—Ben Purkert for Guernica

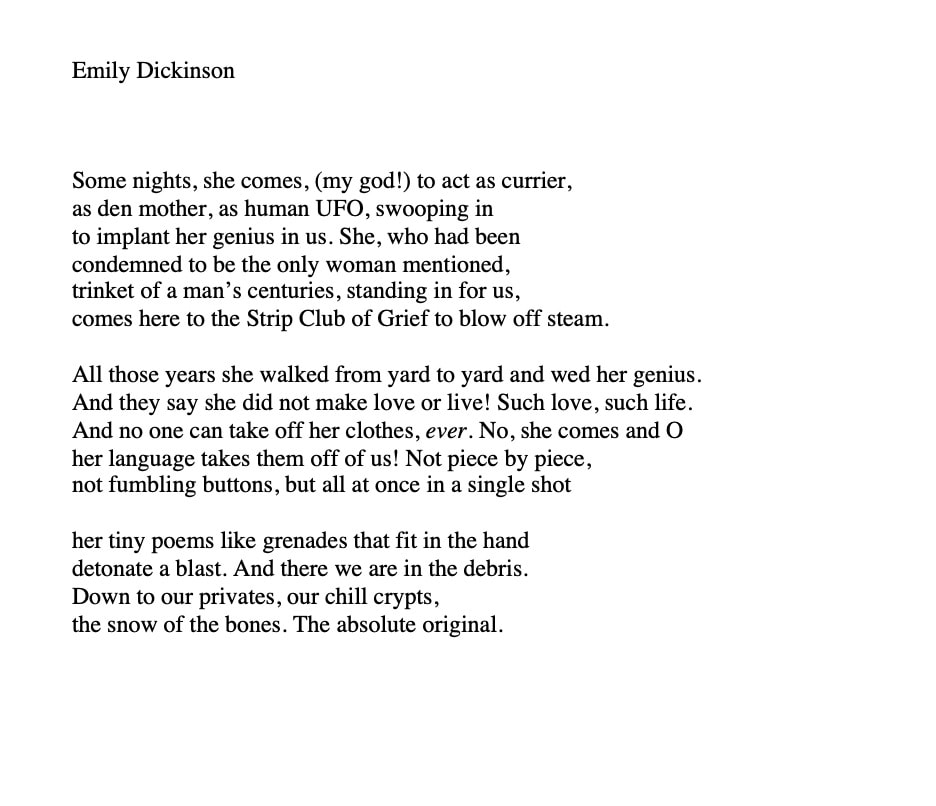

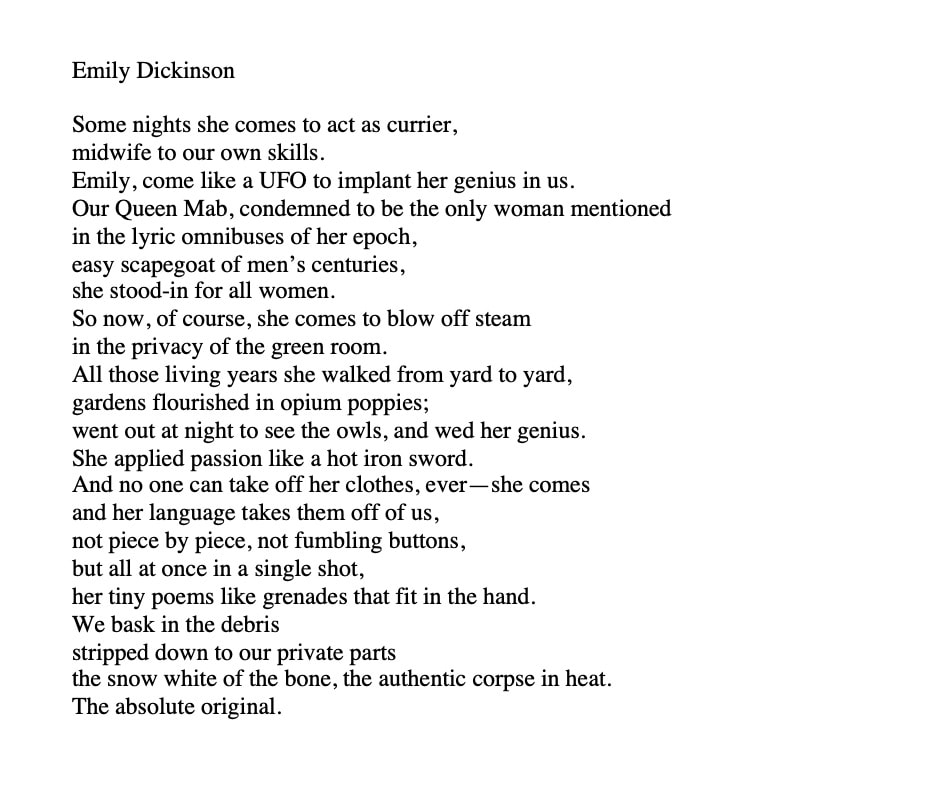

Guernica: How did this poem come to be?

Stone: I was thinking about women writers, especially my grandmother. As a woman poet in the ‘70s and ‘80s, she was up against this very hyper-masculine poetry community that she didn’t get along with very well. And when I was writing this poem, I was thinking about that scornfulness between poets of different genders that’s sometimes in the air. Emily Dickinson seems relevant to all that.

Guernica: In what way?

Stone: She’s such a popular poet, one of the most well-known poets around the world. And often she’s co-opted by male readers’ interpretations of her work. I felt pissed off about it. She was often the lone American nineteenth-century woman poet deemed extraordinary enough to be anthologized, and thrown in as a vague fulfillment. I wanted my collection, The Mobius Strip Club of Grief, to imagine a place where women poets can control their surroundings. I see it as an oddly erotic but also painful environment.

Guernica: Your poem feels to me like a pointed response to Billy Collins’s “Taking Off Emily Dickinson’s Clothes.”

Stone: Yeah, I’m definitely referencing the Collins poem. I know that’s a beloved poem for many people, but for me, it’s indicative of that whole male poetry oppressiveness. To be clear, I love male poets. But that Collins poem in particular is a very telling instance of the sort of co-opting of female voices I’m talking about. I mean, she’s dead and she can’t consent to anything and you’re going to eroticize her in this way? It’s a shame. And look, there’s no reason why we can’t fall in love with poets who are dead. I myself am in love with some of them. We’re all in love with Keats, right? But do I really want to take his clothes off? It’s icky, it’s rapey. I wanted to reclaim her on her behalf.

Guernica: Your poem does that reclaiming in such a powerful way. Instead of Collins taking off her clothes, she’s the one stripping all of us bare.

Stone: I think that for a lot of people who have felt strangled by somebody else emotionally, this fantasy of taking back control is very powerful. Even if this world of The Mobius Strip Club exists only in my book, it’s not just fantasy. It’s a tiny alternate reality. And I like to think that this is just the beginning of rethinking Emily Dickinson’s legacy in many different ways. We’ll never stop mining her work for new insights because she just left so much there. So much ambiguity, and so much symbolism, and lyricism. It’s a wonderful strangeness. We owe so much to her.

Guernica: Comparing your two drafts, I see that you took out the exclamation marks. The tone gets markedly quieter.

Stone: I think I was having fun being over the top in the first draft. I’ve always liked using exclamation points. Early in my college education, a teacher told me that a poet gets one exclamation point in their poems for their entire career. [Laughter] But yeah, I’m glad I had those exclamation points in the original.

Guernica: Why?

Stone: Because it captures my incredulousness. It continues to astonish me the way people try to make her into some chaste, palatable object. How she was such an anomaly in her town, this oddity. And now, thanks to Billy Collins, we can see what’s underneath! Exclamation point, exclamation point. Anyway, I changed the punctuation and reined that baby in and slowed down the pace. Made it more somber, or sardonic even.

Guernica: When did you start feeling so connected to Dickinson and her work?

Stone: Not until graduate school, around 2008, 2009. I’m mad that for so long I dismissed her because of the way she’s presented in education. And then, once you really immerse yourself in her poems, you can’t stop. You start reading her letters and all the biographies. And now there’s all these fun movies about her. She’s like Virginia Woolf; you just never get tired of more.

Guernica: And, like Woolf, there’s a real sense of ownership about her image and what it’s meant to represent.

Stone: Sylvia Plath’s probably the worst in that way. You can’t talk about her without talking about her suicide and Ted Hughes. But it’s all interesting, so who can blame anybody?

Guernica: When did you start writing the poems that became The Mobius Strip Club of Grief?

Stone: The book came out of grief for my grandmother. After she passed, it was a tremendous loss. She was this matriarch that my whole family had been orbiting around. And, as a poet, she’d always been drawn to the elegy, and grief had a massive presence in her life. So when she died, I had this grief that I inherited from her but then also my own private one, for the loss of her. Anyway, I started thinking a lot about the complexity of death and sorrow and family and sexuality and women. I live in a family of women, and all the men leave. And one day I was reading one of my grandmother’s poems called “The Mobius Strip of Grief,” and I thought it was such an incredible title. It really is the perfect metaphor for grief. This ribbon that connects back to itself that goes on and on, like infinity, and just keeps coming back to the same places; that’s often what grief is like in a family. The strip club part, well, that just popped into my head. It led to many other explorations, like researching the history of women who used to host soirees and secret artists’ group meetings. What’s the word I’m looking for? Like a Proustian artist gathering?

Guernica: A salon?

Stone: Right. Artist salons, where people would fight over interpretations of Balzac sonnets. And these women were so important to the cultivation of art and writing, and then were forgotten and ignored. And they themselves weren’t allowed to write or let alone publish, or hold any kind of official educational position they might have wanted. But they were able to foster creativity—their own and others’—through private salons.

Guernica: It strikes me that working in a strip club is many things, but first and foremost it’s a job. It’s a way to pay the bills.

Stone: Oh, totally. And in my family, paying the bills was always a struggle. Keeping a job was always a struggle. It’s weird because it’s different for writers.

Guernica: How so?

Stone: Well, as a writer, you’re doing it because it’s your calling. You love doing it because you’re a crazy masochist, so it’s a different kind of gritty work. Certainly for Ruth, it was constantly about trying to get university jobs and teaching gigs. It’s not the same as sitting around thinking about the beauty of a leaf. Feeding your kids and having to be a single mother is a big job.

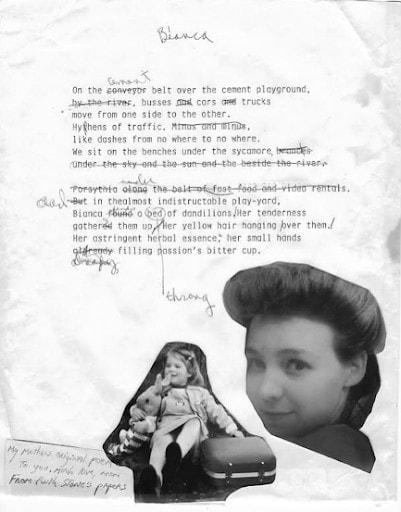

Guernica: Ruth wrote a poem for you titled “Bianca,” right?

Stone: Yes. And then my mom gave me the early draft as a Christmas present. It was after grandma died, and we’d been shuffling through all her papers and stuff. That’s when my mom found it and added the pictures and then gave it to me. You can see me in the photo carrying a suitcase. As a kid, I was always going to grandma’s house. And the picture of grandma is her as a young woman. But she had that same hairdo her whole life. Most people don’t have the same hairdo at 80 that they do at 30, but she was still rocking it.

Guernica: I love that we get to see her edits here.

Stone: As I re-read the poem, I think it must have been from when I was a very young child, around eight or so. With the cement playground and the buses and the cars, I’m assuming I was with her when she was teaching in a city probably. This poem is from In the Dark, a later book of hers. But there’s one thing about this poem that has always bothered me.

Guernica: What’s that?

Stone: In the second-to-last line, it’s that phrase “astringent herbal essence.” I always wondered: Does grandma not realize there’s a shampoo called Herbal Essence?

Guernica: Maybe it’s how she gave her hair such volume.

Stone: She used baby shampoo exclusively.

Guernica: Looking at her edits, I notice she changed the verb tense. “Bianca found” becomes “Bianca finds.”

Stone: I like that edit. Obviously it makes the whole poem feel more present, like it’s all happening right in front of her.

Guernica: Is this poem typical of how she would revise? What did her creative process look like?

Stone: This was pretty much it. I’ve found a lot of her poems indecipherable because there are so many lines edited. It looks like this was done on a typewriter. She’d often write by hand, then type it out on a typewriter to edit. I do something similar. I usually print out a poem after I write it and then edit from there. I also remember how she would tinker with a poem for years, trying to get it right, and then never really feeling like she did.

Guernica: Would she still publish it or just keep it in the drawer?

Stone: Depends. Some you just feel too attached to, they have to be published. You’ve put too much in. Others, you just hate so much and feel so ashamed that you don’t want anyone else to read it. And usually that shame is what keeps you revising.

Guernica: How would you describe your approach to revision?

Stone: I’m 37, and it’s been a lifetime of practice. Just constantly trying to get it right. Revision also means realizing when a poem just isn’t worth revising, when it’s time to write a new poem. Now, over the years, I’ve gotten more in love with the challenge of making something work that isn’t working. Sometimes poems come off kind of easily, and that’s satisfying too, but the radical revision when you bust something open and really take it far, that’s the joy. And I love teaching revision to students. One thing I’ve noticed with new poets is that they often struggle to see what to revise. They can’t see what needs to go and what needs to stay, or even where the poem might be weak or confusing.

Guernica: That’s basically the whole reason why Back Draft exists. I wanted emerging writers to see how more established folks approach revision, so it might demystify the process.

Stone: I think that’s important, because the workshop model often isn’t helpful to teach revision. It’s usually not radical enough. A lot of times workshops try to fix a few tiny little things and it results in keeping your poem mediocre. Whatever. Maybe sometimes that’s all it needs. But in my experience, students are holding back. You should get back in the poem and bust it wide open! With revision, you can do that. You have that freedom.

On the flip side, I will say that a poem often never feels finished, and that’s completely okay. You can get obsessive about revising, but at some point you need to let go and let it live in a book and it will always have more potentiality in it. But there really is beauty in ending the editing process. Letting a poem live, that can be nice.

To read more interviews from our Back Draft archive, click here.