—Homer Simpson

The Reagans stayed at the Renaissance Center, Henry Ford II’s vast, oppressive hotel-and-office complex, which was three years old at the time. Its massiveness and spartan glass architecture have always made the RenCen seem out of place in Detroit’s modernist skyline. The three large steel-and-glass cylindrical towers, ringed by a set of narrower external elevator shafts, are like the shuttlecraft of some hostile space aliens who came to be taken to our leaders but landed in Detroit by mistake. The complex includes the hotel, General Motors headquarters, and a few corporate offices. Its labyrinthine shopping arcades were designed to disorient you, so you’d get lost amid the shops; now that most of those are gone, you just get lost. It is a monument to corporate arrogance and waste. The future president probably slept well.

Reagan’s presidency did the Motor City no favors, of course, and Detroit today remains a place blessedly free of the cult of personality that lingers around the Gipper in most of the country. The 1980s were years of recession, of contraction in the US auto industry, and of huge domestic spending cuts that helped make Detroit, by decade’s end, virtually synonymous with urban crisis. It is this Detroit of decline and violence—not the Detroit of “American Greatness”—that has endured in the American imagination, and nowhere has it been more cruelly and masterfully represented than in Paul Verhoeven’s 1987 RoboCop. The film has enjoyed a new life in recent years—aside from this year’s remake, there is Detroit’s forthcoming RoboCop statue, funded by Kickstarter, which will be unveiled tomorrow and which itself stands as a monument to creative-class arrogance and waste.*

1987’s RoboCop is set in the Detroit of a not-too-distant future, a city where criminals rule the streets and even the militarized police force is underfunded and outgunned. The city government has been privatized by a vast corporation, Omni Consumer Products, which plans to build a gleaming new metropolis—Delta City—on the ruins of “Old Detroit.” Bob Morton, an ambitious OCP executive, develops RoboCop to solve two of the company’s problems: the PR cost of urban crime, and the high price of a human police force. Built out of the destroyed body of Alex Murphy, a policeman tortured to death by local drug kingpin Clarence Boddicker, the cyborg is designed to fight street crime in Old Detroit by any means necessary, and to automate the police force in the process. OCP thus excels in what business ideologues glibly call “creative destruction,” but the grisly opening scene reminds us that somebody else—indeed somebody else’s body—ends up getting destroyed. The film starts out as a familiar sci-fi story in which the cyborg, tormented by residual memories of his human life, sets out to find the man who killed Murphy. He soon learns, however, that the real criminals are in the executive suites.

The film’s landscape is a jumble of generic places that can be found in any deindustrializing metropolitan area in America.

RoboCop was filmed in Dallas, and the place names that appear in the movie—like 3rd and Nash, where RoboCop stops a gas station robbery—don’t exist in the actual city of Detroit. The film’s landscape is a jumble of generic places that can be found in any deindustrializing metropolitan area in America: nondescript industrial ruins, with rusted cranes and toxic waste vats, where the gangsters congregate; the landscaped, suburban cul-de-sac where Murphy lived; the derelict inner city of liquor stores, gas stations, and empty streets; and the towering steel-and-glass headquarters of OCP. Detroit’s foremost industry appears only twice, unless you count the automation of police work, which mimics what happened to automotive assembly lines. The first mention of it comes in a commercial for the 6000-SUX, a car that gets 8.2 miles per gallon (“An American Tradition,” the commercial proudly intones); the second in RoboCop’s appearance at the Lee lacocca Elementary School, where he entertains schoolchildren taught to revere the Chrysler mogul.

The true setting of the movie, in other words, isn’t Detroit, Michigan, but the idea of Detroit that has endured in the national imagination. This Detroit is what the media historian Steve Macek calls the “urban nightmare” of 1980s mainstream media, in which big cities from Washington, DC, to Los Angeles became “vast landscapes of fear, seen as teetering on the verge of an impending apocalypse or already smoldering in ruins.” This vision of the city emerged in various action films of the era, especially those set in New York and LA: John Carpenter’s Escape from New York, vigilante films like Death Wish, and police comedy-dramas like Lethal Weapon and Colors, to name a few. RoboCop carefully avoids considering the role of racism in this “landscape,” however. Metro Detroit remains today a deeply segregated place; the city, the population of which was 75 percent African-American by 1990, is still surrounded by suburbs with white majorities and most of the region’s wealth. Yet the criminal gang in RoboCop is racially integrated, and most of the Detroit residents we see are white.

But the doomed Old Detroit of the film does ring true in other ways: it is a city with no obvious economic basis other than its own destruction, an echo of today’s Detroit, where scrapping buildings is an employment of last resort, demolition is an economic development policy, and the city’s indebtedness is the raw material out of which Wall Street manufactures big profits. Even after taking what the media loves to call a “haircut” in bankruptcy court, Detroit’s creditors, like UBS, Barclays, and Bank of America, still stand to make hundreds of millions on their loans to the impoverished city. (In a way, a “haircut” is an apt symbol for making slightly less of a fortune than you thought you might: haircuts are painless, and you can always grow more hair.) There is something quaint about OCP, by comparison. A vertically integrated corporation that controls every aspect of the city-making process in Detroit—from construction and policing to street crime and entertainment—OCP is old fashioned, more like Ford in the days when it made all of its steel, rubber, and glass under one roof at River Rouge. The Wall Street creditors have none of OCP’s minimal responsibilities to the city.

RoboCop is gratuitously violent, set in a world where American greatness is besieged by sinister, malevolent forces.

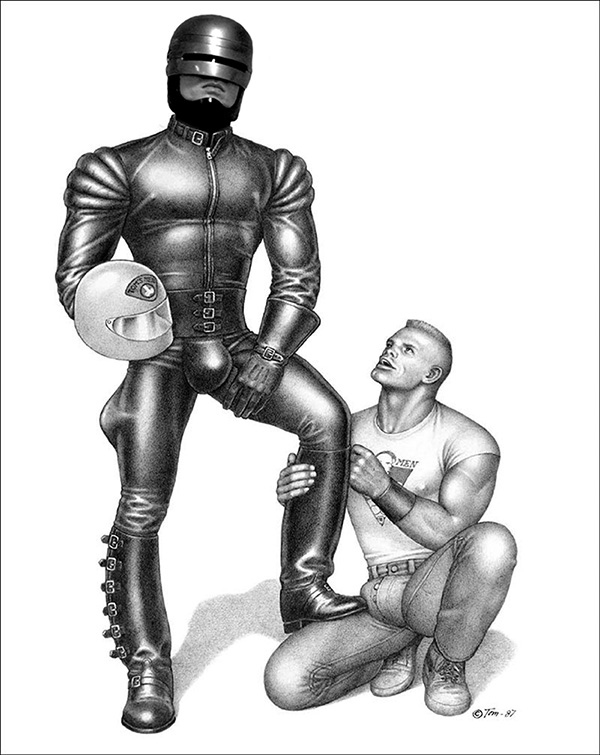

RoboCop grossed over $8 million in its opening weekend, in the summer of 1987, a few months after Mel Gibson and Danny Glover’s Lethal Weapon, and was the sixteenth most successful movie in America that year. Like most of the Reagan-era action films it parodied and parroted—the Gibson/Glover franchise, Rambo, Die Hard, The Punisher, Commando, Predator, and earlier vigilante films like Death Wish—RoboCop is gratuitously violent, set in a world where American greatness is besieged by sinister, malevolent forces like drug dealers, Communists, terrorists, gangsters, and extraterrestrial sport hunters. Similarly, RoboCop renders what cinema scholar Susan Jeffords calls the “hard bodies” of American male heroes as the civilized world’s final line of defense against the “soft bodies” among us and the freedom-hating bad guys. From Sylvester Stallone’s sweaty pectorals and Carl Weathers’s bulging biceps all the way down to the anguished soles of Bruce Willis’s bare feet: these heroic bodies are “masterful,” Jeffords writes, “as in control of their environments (immediate or geopolitical), as dominating those around them (whether they be the soft bodies of other citizens or of enemies).” Fighting both the amoral enemy and the cowardly bureaucrats who would hold them back, these men are appealingly unhinged and coolly efficient. As Jeffords argues, RoboCop’s hard body represents the redemptive hope of violence—he “cleans up” the city by shooting as many criminals as possible—along with the fear that engaging in such violence would make us little more than machines ourselves.

RoboCop does a good enough impression of an action film to serve as one of the genre’s most popular examples (a reviewer in the New York Times panned it as a thoughtless carnival of violence, missing the satire, just as I did when I got it on VHS as a twelve-year-old from the neighborhood video store that kindly rented R movies to my brother and I). But it also mocks the genre and the militaristic popular culture that created it: the film is punctuated by a Greek chorus of television clips, from sensationalist, crime-obsessed local news segments (anchored by Entertainment Tonight’s old host, Mary Hart) to television commercials for things like “Nukem,” the family nuclear-holocaust board game. The film’s most brilliant parodic element, though, is its use of the most reliably unfunny entry in the comic lexicon: the knee (or foot or fist or projectile) to the groin.

This essay will now turn to RoboCop’s crotch. What can it tell us about the country we live in today, the country that stumbled out of Joe Louis Arena on a summer evening in 1980, right into a decades-long kick in the pants?

Attacking RoboCop’s crotch is so often the last desperate move of his enemies. The bad guys, having seen the movies, assume that RoboCop’s strength lies there. After they have emptied their clips, their bullets clanging harmlessly off his hard metal torso, they kick RoboCop in the groin, and get nothing but sore feet for their trouble, and then their final, usually fatal punishment. It’s an understandable impulse: RoboCop’s metallic armor doesn’t connect his legs and torso, and his crotch appears to be made of some sort of black rubber, exposed and inviting attack.

Mention RoboCop in casual conversation and someone will invariably utter Bixby Snyder’s catchphrase. (Write the word “RoboCop” on Twitter and a Bixby-bot will reply in seconds—really, try it.) Snyder is the comedian who appears on TV throughout the movie, leering, “I’d buy that for a dollar!” as women hang off each arm. His popularity demonstrates how easy and lucrative it is in OCP’s world to debase yourself by humiliating others. The object of the kick in the groin is male, of course, but the catchphrase and the kick operate in similar ways. Like Snyder’s tagline, the groin assault is, taken on its own, grotesque, juvenile, and unfunny. It only becomes funny referentially, when you are telling jokes about blows to the groin, or better yet, jokes about jokes about blows to the groin. Thus, this classic Simpsons episode, in which Homer votes Hans Moleman’s “Man Getting Hit By Football” winner of the Springfield Film Festival: we begin by laughing at Homer’s stupid sense of humor, but we end up laughing with him, sharing his populist exuberance at the joke’s simplicity. Crude and cruel as it is, the sight of Hans Moleman getting hit in the crotch by a football that makes a springy sound on impact actually is kind of funny, especially when the New York film snob presiding over the contest sniffs at Homer, and at us, “This isn’t America’s Funniest Home Videos!”

Strikes at RoboCop’s groin aren’t the only “dick jokes” in the film (there is not enough space here to catalog them all; I am using the designation broadly). The cheapest one may be the first: Ann Lewis, Murphy’s partner, whose bravery and toughness are established early on, is momentarily distracted by the exposed penis of a gangster who is taunting her—and her lapse leads to Murphy’s death. In another instance, the members of Boddicker’s gang, having gotten their hands on one of OCP’s experimental superguns, take target practice in Old Detroit, bracing the enormous weapon between their legs. (Boddicker takes aim, appropriately, at a brand new 6000-SUX, a phallus stand-in recently acquired by Lewis’s flasher.) And in one of the film’s most harrowing sequences, RoboCop stops an attempted rape by shooting the assailant in the crotch, through the victim’s skirt. It’s harrowing because the film allows the assault to go on for so long before RoboCop intervenes, and also because the gunshot—the gruesome wound to the would-be rapist and the bullet’s tearing of the woman’s skirt, which makes it look as though she’s been raped—is played for laughs.

RoboCop satirizes the action genre by emphasizing its homoerotic undertones.

When a disgruntled city councilman, stripped of his powers, takes the mayor hostage, he negotiates with Hedgecock, the Detroit police lieutenant. The councilman barks at him: “Don’t jerk me off! When people jerk me off, I kill them!” (He then asks: “You wanna see?”) A lapdog OCP executive is named Johnson; OCP’s vice president, the film’s arch-villain, is Dick Jones. A pivotal confrontation between two rivals, which takes place in the OCP executive washroom, features a close-up crotch shot of a terrified junior exec wetting his pants. This is followed by Dick’s confession that he once called his boss “Boner” and “Iron Butt”; Jones’s erotically charged caressing of Bob Morton’s perfectly sculpted business hair; and finally, Bob’s breathy repetition of the word “dick” as he and his boss stand nose to nose in the men’s room. RoboCop satirizes the action genre by emphasizing its homoerotic undertones; during Bob and Dick’s bathroom confrontation, they seem just as likely to make out as to punch each other. As the literary scholar Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick famously argued, in typically male settings like the corporate boardroom or the US Senate, the exaggerated performance of heterosexual masculinity also masks an anxiously repressed same-sex desire. In the action film, defined by its violent excess and celebration of “hard bodies,” this desire is everywhere visible, yet nowhere acknowledged.

In RoboCop, there is no possibility of pleasure—where you might expect sex, there are only shots to the groin. In this respect, RoboCop is actually last in a sexless lineage: Bronson’s vigilante begot Stallone’s Rambo who begot Schwarzenegger’s Predator warrior who begot his Commando character, none of them involved in a single heterosexual romantic plot. Those characters’ heterosexuality is either implied by their machismo (see Rambo, especially in the shirtless sequels set in Vietnam) or their paternal leanings (Schwarzenegger in Commando and Bronson in Death Wish take up guns to save their daughters). RoboCop is completely chaste, though. His crotch is not only indestructible; it’s also non-functional. In fact, RoboCop has no human appendages. (“I thought we agreed on total body prosthesis!” Bob Morton shouts at OCP’s scientists early in the film, when he orders them to “lose the arm.”) Despite the fact that he is, in effect, nude for the duration of the film, the cyborg has no love interest, not even his attractive female partner. And Murphy’s human memories, of a loving wife welcoming him home from work and carving Halloween pumpkins with an apple-cheeked son, are straight out of a family sitcom. (So there is none of the semi-eroticism that occurs in the classic reunion between Schwarzenegger and Weathers at the beginning of Predator, when their handshake turns into an intense arm-wrestling showdown. Is it going too far to suggest that the film punishes Weathers’s indiscretion later, when the Predator severs that same arm, leaving it writhing on the jungle floor, still squeezing the trigger of his machine gun?)

A typical sequence comes in the middle of the film, when RoboCop is at the height of his powers, the scourge of criminals in Old Detroit. A man armed with a machine gun is holding up a liquor store—apparently the last liquor store in the Rust Belt without bulletproof plexiglass—tended by an elderly white couple, the perfect Sympathetic Victims. RoboCop lumbers robotically into the store as the burglar fires shot after shot, screaming, “Fuck Me! Fuck Me! Fuck Me!” His bullets ricochet off RoboCop’s metallic pectoral muscles. RoboCop calmly disarms him by bending the barrel of his gun downward, making the machine gun flaccid. Our hero’s hard, chaste body wins the day, and as the burglar lies unconscious, his head lodged in the beer fridge, the TV chants, “I’d buy that for a dollar!” What would the bald, middle-aged creep with cake frosting on his face buy for a dollar? Better we don’t think too much on it. The joke, like Hans Moleman and the football, becomes funny, finally, through ironic repetition.

Remember, there’s no sex in this movie, only violence masquerading as sex.

I prefer to read the criminal’s exclamation, “Fuck me!” more as a request than a frustrated lament—a request for RoboCop to, in fact, fuck him. The outcome of the scene is what it means to be “fucked” by a sexless cyborg; remember, there’s no sex in this movie, only violence masquerading as sex. The Bixby Snyder clip that ends the scene reminds us that sex is ubiquitous in this world, but that it is cruel, authoritarian, pleasureless, mocking—it puts you in your place. “Fucking” is a kind of discipline, delivered by the hard body looking out for you, and the citizens of this city ruled by private enterprise have been taught to want this kind of discipline, to think they need it. And what about us, the audience (or at least the audience Verhoeven imagines)? We are cheering, after all, for the heavily armed weapon of a sociopathic corporation. We all want OCP to fuck us, for at most a dollar. RoboCop mocks our desire to be “fucked” (over) by a miserly corporate state and our relief to be getting it for such a bargain. This, actually, is the biggest “dick joke” in the film: the Reagan-era fantasy that tough guys with hard bodies and clean minds, whether on screen or in Congress, can save us from the disaster we have made of our cities.

This fantasy has survived the 1980s, of course, even as the action genre that spawned RoboCop has faded. Meanwhile, the market fundamentalism and “tough-on-crime” rhetoric that the film makes fun of, still relatively novel in 1987, have today become normalized. The idea of redemptive violence—mass incarceration, a heavily armed police force—is now so deeply embedded in our political culture that we may no longer be able to see it well enough to mock it. RoboCop is thus both more dated and more current than ever. Its critical edge comes from a pessimistic vision of the future that is getting closer all the time.

* The RoboCop statue was theoretically “crowdfunded,” but most of the money came from the San Francisco branding firm OCP—named after the corporation in RoboCop—that specializes in producing fictional products from movies for the real world. Cute, no?