After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Cuba lost its longtime benefactor and fell into crisis. For Cubans, “the special period,” as it is known, were years of pronounced scarcity, hunger, and political repression. Around the same time, a military coup sponsored by the United States propelled Haiti into turmoil. During that era, tens of thousands of Cubans and Haitians fled their homes, many taking their chances on precarious rafts. The United States military intercepted thousands of those refugees, and for months, sometimes years, detained them in camps at Guantánamo Bay. Aurora De Armendi, then aged fourteen, was among those detained after she and her family fled Havana on a raft. De Armendi, now a printmaker and a filmmaker, has confronted the experience in her work.

I spoke with De Armendi about two of her recent works. EntreVistas, her multi-channel video installation, centers on interviews with Cubans once held at Guantánamo Bay—starting with De Armendi’s mother. For that project, De Armendi charged herself with getting answers and sharing the stories.

More recently, as she was making Libro de las Preguntas (A Book of Questions), a set of ten handmade books, De Armendi’s perspective shifted—rather than ask former detainees to offer up their stories for public consumption, she wanted to create for them a way to experience their memories privately, without agenda. De Armendi was trained as a printmaker at Cooper Union and the University of Iowa, and anyone can appreciate how careful and beautiful each book is. But De Armendi designed Libro de las Preguntas specifically with viewers who had been at Guantánamo in mind. The text alternates between Spanish, Haitian Creole, and English. Libro de las Preguntas supplies no answers, only questions that open memories for De Armendi and others who were detained. A book is read privately, she points out. And so this book is intended to give each reader access to his own private memories—of surrendering everything familiar, of being trapped for months, of sea and sky—without demanding that he or she translate, share, or perform. Each reader can spend time with the questions, conjure her experiences, in her own language, on her own terms.

De Armendi told me that she likes paper because it’s “humble,” meaning breakable, and yet it is because of paper that we have been able to transfer knowledge between people and generations. Her ideas humble me, too. In a time when public life demands rigid principle and loud participation, when large groups of people, especially migrants, are being shoved into categories, forced to defend themselves literally and figuratively, Libro de las Preguntas is a quiet refutation of the arrogance of thinking that we know, that we deserve to question—let alone speak for—someone else.

—Meaghan Winter for Guernica

Guernica: Why did you decide to work with paper and to make books?

Aurora De Armendi: Working with paper connects me to the labor involved in making it and its history but also offers different possibilities [for] making work, as each paper is a different, color, weight, [texture]. Maybe I’m also very aware of this material because growing up I didn’t have that much of it. I remember writing, at school, in notebooks made out of brown recycled paper. Paper was very scarce in Cuba in the late ’80s and ’90s.

I had the opportunity to learn papermaking from Cara Di Edwardo at the Cooper Union and also from Timothy Barrett at the University of Iowa. During this time, I learned to appreciate the work involved in making a sheet of paper, from the selection of native plant fibers to the labor involved in cooking [them], separating good from bad, beating the paper by hand or using a Hollander beater and then forming the individual sheets.

The field of bookmaking is very interesting to me. The time-based nature of books, the intimacy of reading, the flexibility of viewing anywhere by the afforded privilege of mobility are all things I think about when I make books. Also, I’m interested in the viewer interacting with the haptic qualities of the book.

Guernica: Do you remember a moment when you decided, “I’m going to make work about Guantánamo?”

Aurora De Armendi: I was in Iowa City finishing my master’s in printmaking with a minor in intermedia, and I would visit my parents in Florida. Cubans in Miami tend to discuss politics quite often. It is very common to hear these conversations, for example, in the Versailles Restaurant on Calle Ocho. Cuban people sit and have lunch with un cafecito and the conversation about politics begins [laughs]. There is this overall attitude of having assimilated, but this overarching question of, “What is going to happen when there is a change in government on the island? Do we go back to stay? Do we stay here in our host country?” These are questions that not only pertain to Cubans but to all diasporic communities.

As someone who was a refugee at the Naval Base in Guantánamo when I was fourteen years old, my work about exploring Guantánamo as a place began with questions I wanted to answer for myself. I wanted to know more about my history and also about how we [as Cubans] experienced Guantánamo collectively. How many waves of migrations have we experienced since the 1959 revolution? I had the need to talk to people who had left in the ’60s, who had left in the ’80s, and people who also experienced Guantánamo with me but that were older or younger, or a different race or gender.

[I started doing interviews] using my video camera from the University of Iowa and a microphone. Most of the people I interviewed had also been in Guantánamo as refugees. EntreVistas was inspired by the work of Belgian film director and artist Chantal Akerman, who unfortunately passed away recently. In 2009, I saw a retrospective of her work at the Pérez Art Museum Miami—From the Other Side, a work filmed on both sides of the border between Arizona and Mexico, in which she explored the endurance and resilience of Mexican immigrants as they cross the border for better opportunities. The film was shown on eighteen video monitors and two projection screens. The full work was comprised of interviews, long shots of the wall that was being erected between Sonora, Mexico, and Arizona, as well as surveillance video from the US Border Patrol.

Guernica: How did you find all these people to interview?

Aurora De Armendi: Mostly I would talk to my parents and [they would say], “You know what, this person has a really interesting story, you should see them.” I would tell a friend and slowly people were recommending friends for me to speak with. It was not targeted [outreach]. This took a few years. The first interview was with my mother.

My father is a doctor, but he couldn’t practice in the United States for many years. At the time he was a volunteer in Puerto Rico. He was doing a whole year of volunteer work so he could get his license in Puerto Rico and eventually in the United States. Now he’s practicing. My mother happened to visit my father, and she said, “Come visit us.” I remember traveling from Iowa with a camera and a tripod and my microphone, and I said, “Mom, I’m starting this project and I want to interview you and my dad first. I want to learn why you decided to come to the United States.” I also told her during this process that I was very uncomfortable to be caught up in that space [as a fourteen-year-old] where you cannot make decisions for yourself, and parents make such an important decision for you, such as leaving your country of origin.

Guernica: They held you there while immigration was processing your visa application?

Aurora De Armendi: At the time Bill Clinton was president. They were trying to figure out what they were going to do with thirty thousand [Cuban] refugees. So then Panama made an agreement and took a large portion of Cuban refugees. My parents decided to stay at Guantánamo to wait to go to the United States when permitted.

Guernica: How did it go when you interviewed her?

Aurora De Armendi: It was beautiful. There were moments when we connected. There were moments of understanding; me understanding her choices, as an adult. So there was a lot of reconciliation. She did the best she could under those circumstances. She was very courageous.

Guernica: Just to agree to the interview!

Aurora De Armendi: Yes, to agree to the interview was very courageous, but also the choice of putting her children in a raft to leave the country.

Then I started interviewing my dad. I put the microphone on the table in front of him and started to ask him questions and he said, “I can’t do this.”

Guernica: What do you think that is? Masculinity? His personality?

Aurora De Armendi: Maybe it was too painful to have it brought to the surface.

Guernica: To have to acknowledge what happened.

Aurora De Armendi: Yes. But also, he was a doctor in Cuba. He had a really significant career. It was his identity. And here he was at the time in Puerto Rico with more than twenty years of experience as an internal medicine doctor doing volunteer work so he could practice in his field again. All of the discrimination [and] ageism he had to go through to get to where he is right now, I was reinforcing [all of that] for him.

Guernica: You could have had the impulse to go as far away from your parents as possible and start the interviews with strangers.

Aurora De Armendi: That’s true, but I wanted to begin with them. They’re very supportive of what I do.

Guernica: Does it feel like a choice for you to make political work? You make nonpolitical work too, but does the part of you that makes political work feel optional?

Aurora De Armendi: I move between making work that is abstract. For example, my color books and work that it is more direct confronts or questions a biographical topic, a collective memory or a forgotten history. Migrations have existed since the beginning of humanity. I think my work will always have the viewpoint of an immigrant, whether conscious or subconscious. My experience of migration has changed the way I see the world and definitely the way I make art.

Making EntreVistas was very emotional at times. It was very eye-opening at other times. I witnessed stories of resilience and adaptability. And failure too. The things that you aspire to, the American dream. Then you realize that in your country you were better off for many different reasons. Maybe you didn’t have the best comforts but you had more of a communal way of living, a society more civically engaged or free healthcare and education, basic human rights.

Guernica: When you were interviewing people who’d been in Guantánamo, was there something that came across as a common thread that you wouldn’t have anticipated?

Aurora De Armendi: I think something that stuck out is this Cuban pride. In many of the interviews, there was a sense of gratitude toward the United States for allowing us to enter this country. There were many heroic stories, but also a need for a heroic narrative. Antonio, [a man I interviewed for this project], didn’t see his daughter grow up. By the time he took his daughter and wife out [of Cuba] so much time had passed that there were familial ties but estrangement as well.

This process made me think of the things we sacrifice when we make the choice to migrate, for political reasons, for economic reasons, to escape war or famine. You lose or gain, it can work both ways. When Cuba broke ties with the Russian government, the amount of improvisation of the Cuban people was amazing. We had so little, yet we kept going, and with a great sense of resilience, pride, and humor. I think about [how] I didn’t get to grow up with the same circle of friends. That I returned to my country after seven years in the United States and felt like a stranger in my own home. I feel like at times we act as if it’s okay. But it would be good if among ourselves we could show our vulnerabilities as well and stop pretending that we are so strong. The fact is that it has been hard and tragic at times, our collective story.

Guernica: How did you get the idea for your book project Libro de las Preguntas?

Aurora De Armendi: The idea for Libro de las Preguntas evolved from the EntreVistas project. I did not want to only address the Cuban experience in Guantánamo, but the experiences of the many groups that were also at the camps in the early 1990s. By the time thirty thousand Cubans arrived in Guantánamo in 1994, there were already Haitian refugees living there since 1991. All of the Haitian refugees fled by boat after Jean-Bertrand Aristide, the democratically elected president of Haiti, was overthrown and his followers were persecuted by the military government. Sometimes when I close my eyes, I remember the employees of Guantánamo, the social workers, the translators, the doctors, you know, the Marines that were there on a daily basis. Adjacent to our camp there were Haitian camps. I remember all of them.

So in Libro de las Preguntas I was thinking about the idea of coming up with fifteen questions to remember GTMO as a place, to think of that context. I wanted to make a book of questions in which the three different languages I encountered at GTMO could be represented in the book: Haitian Creole, English, and Spanish.

I was also thinking about how the book itself could show, in the sequence of pages and in the questions, a recalling of our memories. The edges of the paper in the book could potentially serve as metaphors for the perimeters of the camps. Sometimes we wanted to communicate with the Haitians of the neighboring camps, yet we were unable to understand them, so we had to ask for a translator to come. In the physical form of this book, I wanted all of these concerns to be communicated.

[Reads from the book] How long were you detained in the camps?

In some cases, there are only questions in Haitian Creole and English. Someone who finds herself reading the book and only knows Spanish might experience a sense of displacement in a particular part of the book as he or she can’t understand the language.

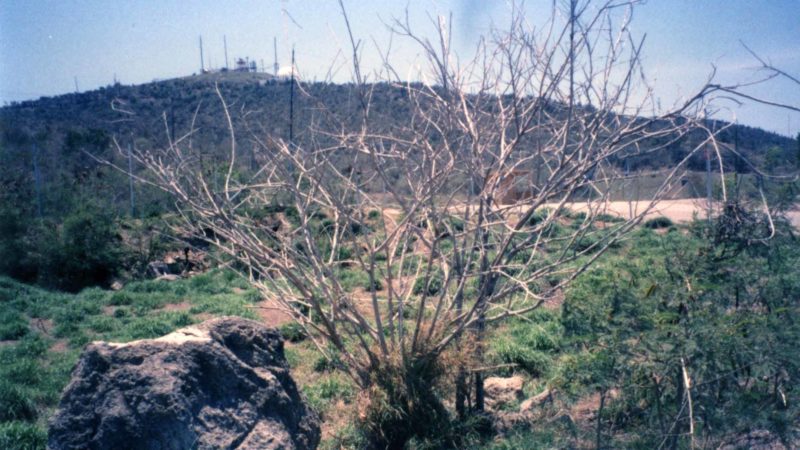

How would you describe the landscape of Guantánamo to someone who has never been there?

Guernica: How did you get the idea that questions would make up the book?

Aurora De Armendi: I was looking at archival material such as photographs, letters, newspapers clippings, cartoons made by artists at the camps, and I knew that I didn’t want to make a book of images. I felt language could communicate more by merely asking questions. So were you a refugee or an employee? It’s all about the gaze, right? What do you see? How do you remember the landscape? What job did you perform?

The book creates an idea of no hierarchies between the three groups of people. Or no differentiating between refugee or employee, but instead how we shared a common ground, a place. I worked with a Haitian translator in New York. I asked a few friends to revise the questions, [including] my brother [and] my partner. Many people were involved in reading these questions and helping with translations.

Guernica: What is your name? comes toward the end, not at the beginning.

Aurora De Armendi: Oh, yeah. At the camps you were identified by a number, the Marines would scan our wrists when we would enter or exit the camps. So asking the simple question of “What is your name?” had to be in the book. You’re identified by this—a plastic bracelet where the military would scan our identification numbers. It was fixed onto our wrists.

This belongs to this young man I met in Miami who at the time was working at The Cuban Heritage Collection at The University of Miami. His name is Jorge. He was five years old when the Cuban refugee crisis happened at GTMO. His wrist was very tiny so they put the plastic bracelet on his ankles.

When I was working on this project, I went to Chile for another project and I learned about Pablo Neruda’s work The Book of Questions, which he wrote three months before he died. I remember realizing how the choice of making the poems as questions generated more questions than the ones written in the book.

Back in the United States and as part of my research, I participated in a few conferences through the Guantánamo Public Memory Project. I visited Tulane University and Brown University, and I was talking to people who were refugees in GTMO but also employees such as social workers, priests, etc. When I was writing the questions, I had the expectation that these questions needed to be answered, was hoping for definitive answers. In the process I realized that this was the [reader’s] choice.

Guernica: It feels like you’re asking a lot of people.

Aurora De Armendi: Right! At first, I was thinking of different ways [to get the answers], like, “Oh, I’m going to write a questionnaire and send it to people I know.”

The Book of Questions by Pablo Neruda reminded me to relinquish control of what you intend artwork to do for others, because the experience of the maker is very different from the experience of the person who is receiving the work. As I was hearing all of these stories, I was processing how the act of sharing might be easy for some people but difficult for others. Some people might not be willing to talk, or maybe their way of answering questions is not the way that we want these questions answered. Or maybe they’re more interested in answering other questions.

The act of questioning and also the one-on-one viewing of the book—the physical relationship and how the questions are organized—allows the viewer to ask these questions in an internal way. It’s not necessary for me to know the answers anymore.

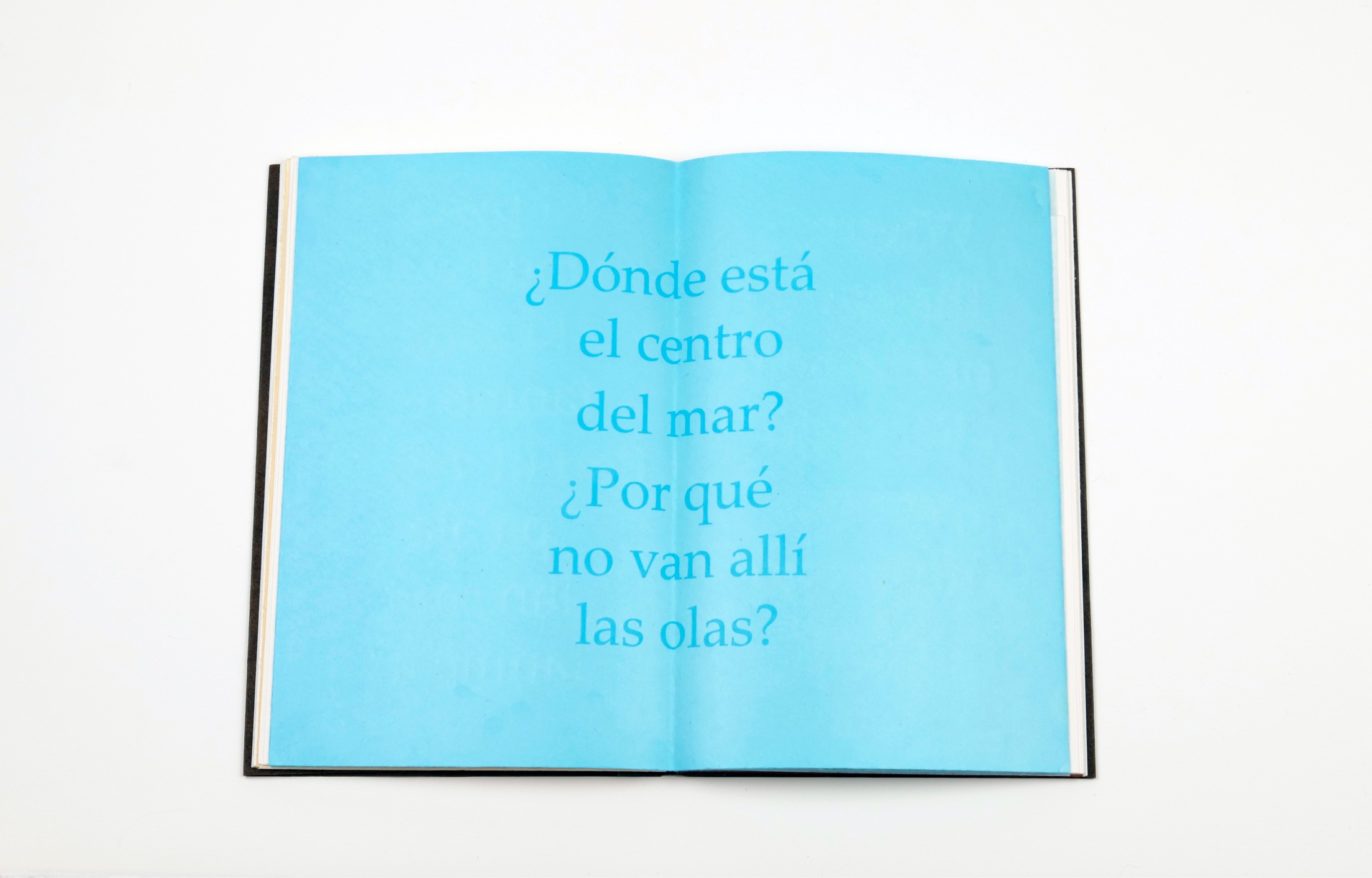

Guernica: You used some questions from Neruda’s The Book of Questions. How did you choose which to include?

Aurora De Armendi: I selected three questions. These were silkscreen printed on paper.

[Reads from the book]: How long do others speak if we have already spoken? This question pointed to this idea of a potential dialogue that can take place after a story is shared.

Because the questions alternate between languages, on a page like this you can only confront the Haitian Creole. I don’t speak the language, therefore I’m not sure which question [the book is] asking. That experience of not understanding returns the reader to an estrangement that reflects not understanding the languages spoken in the camps.

[Reads from the book]: Where is the center of the sea? Why do waves never go there? How did we arrive in Guantánamo? Via sea. The sea becomes a central character in our migration stories. The vehicle. What’s in between two bodies of land. I think refugees or people who emigrate—or at least my parents, since I was too young at the time—always have their eyes on the other place. You’re leaving something behind, but your focus is on where you will be. This question defies any kind of logic, you are not looking back at the place you left behind, nor are you looking to the place you are migrating to, but rather at the center of the sea. We all know there is no center, but Neruda makes us think of this center we all imagine after reading his words, by imagining we already become closer to the potential that it can exist.

The last question [is] also a beautiful question. [Reads from the book]: How many weeks are in a day, and how many years in a month? [It] made me think of not being able to track time in the camps. There were no clocks around. That area of Cuba around Guantánamo is very dry, a desert-like landscape—the seasonal changes are not as visible. At the camps, we knew time was passing, but overall our day to day experiences were very monotonous as [my family and I] were confined to one place surrounded by a barbed-wire fence. In the last months of being at Guantánamo we were able to leave the camps and go to the town’s church because my brother began playing the piano at Sunday Mass.

Guernica: A Cuban church?

Aurora De Armendi: An American Church in Cuba, but on American territory. My brother made friends as he played the piano on Sunday mornings at the local church while my mom and I would wander on the church’s grounds. He and I were invited to this woman’s house; I think her name was Sandy. We were having lunch at a circular table with an umbrella protecting us from the sun and I remember looking at my wristband because I was just scanned out of the camp [for the visit] and there I was trying to understand what this woman was communicating with my brother. I could hardly understand anything because I didn’t speak the language. My brother knew some English and he was translating here and there, but we were still grateful for being able to exit the camps for a little while, even going for a ride in the car.

Guernica: And can you tell me about the reading of this book?

Aurora De Armendi: I am a co-founder of Grupo < >, a collective of women artists from Latin American, the US, and the Caribbean. This past March of 2017, we organized an exhibition at the Instituto Cervantes with the support of the Cuban Cultural Center of New York. Together with the exhibition, we [Grupo founders] wanted to have a series of Satellite Projects organized at different venues in the city. This was primarily an idea the curator Carolina Castro Jorquera and one of our founding members, Constanza Alarcón Tennen, suggested in the proposal for this project. We did a series of events, [including] a video screening at the New School organized by Constanza [and] a reading at Pioneer Books organized by Alva Mooses. Since I had shown Libro de las Preguntas at different venues in Miami and New York, this time the curator suggested I do the reading. I decided to do it in the three different languages. I invited Betsy Campisi, who worked at GTMO during the Cuban refugee crisis [but whom I didn’t meet until 2012 through the Guantánamo Public Memory Project]. She read the questions in English. I also invited Haitian American artist Rejin Leys, who helped with the Haitian refugee crisis in New York in the early ’90s. She read the questions in Haitian Creole and I read the questions in Spanish.

The reading was an experiment, to hear for the first time the three different languages presented in the book. We each held a copy of the book as we read. It is worth investigating what happens in the act of listening rather than reading privately. It was important to me to invite two friends who knew GTMO as part of their experiences but also had a connection to either the Cuban or the Haitian refugee crisis of the early 1990s. The reading took place on 584 Broadway [on the sidewalk], in front of what used to be the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art in New York, which was in operation from 1985 to 1990.

We have been witnessing the crisis of Syrian refugees. Now more than ever we need countries all over the world, including our country [and its current administration], to be more empathetic toward refugee families displaced by war and climate change. I was only at Guantánamo for ten months as a fourteen-year-old girl. I can’t imagine being confined to a camp for more than a decade and growing up under those circumstances. Nor can I imagine groups of people not showing any empathy [and] not pressing their government to help. The reading of [Libro de las Preguntas] was a symbolic gesture but hopefully a display of how art has the potential of making us more human and empathetic of the other.