Thirty thousand terrestrial plants are known to be edible. Yet today, 75 percent of the world’s food comes from just twelve plant, and five animal, species. We grow fewer diverse varieties in favor of high-yielding, industrial crops, reducing—seed by seed—our bonds with regional fruits, vegetables, and grains. We forget how to grow them, how to cook them, how to savor them. When diversity is lost, crops go extinct.

Visual artist Sophie Munns has made the preservation of seeds the center of her artistic practice. Hailing from the subtropics of Australia, Munns employs seeds as a central theme in her sketches and paintings, creating art that demystifies botany and serves as a reminder of the source of so much of our sustenance. Her love of seeds took root in her rural upbringing: “Watching the life cycle of plants play out in my garden—seeds coming to life, dying off, and finally coming to life again—began to have a startling effect on my understanding of the workings of nature,” she told me. “I could ponder past, present, and future through the lens of seeds.”

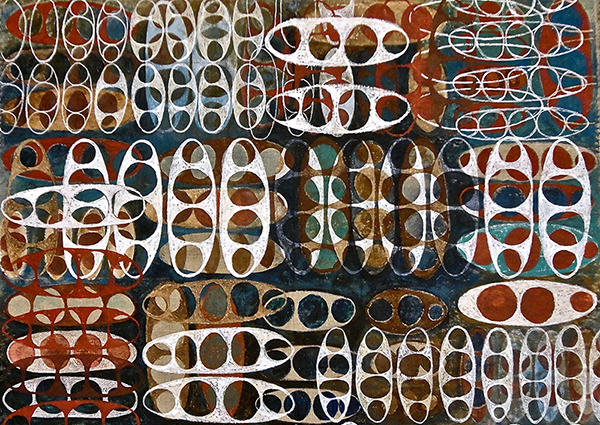

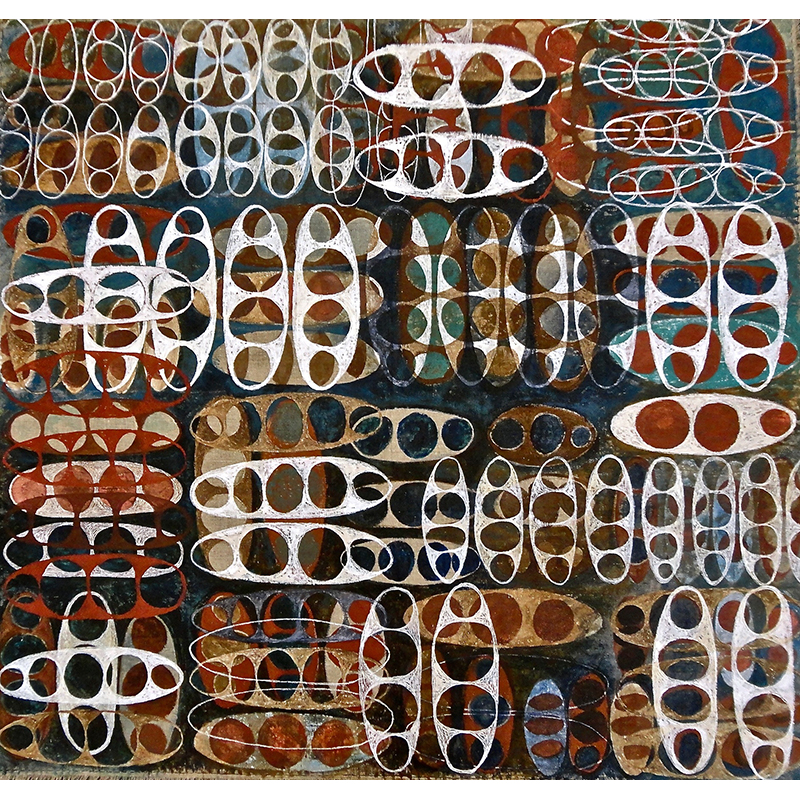

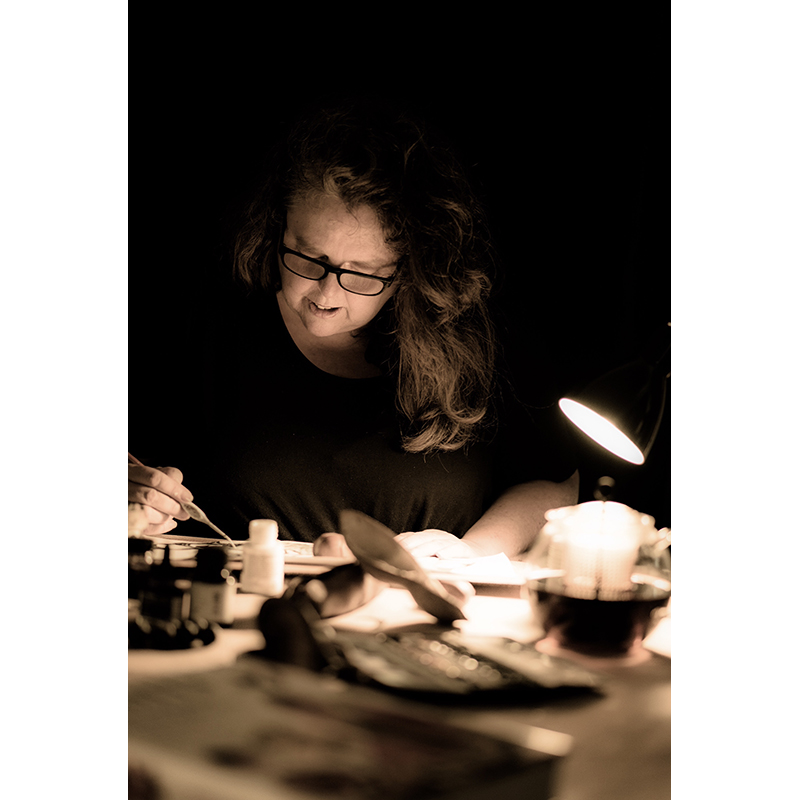

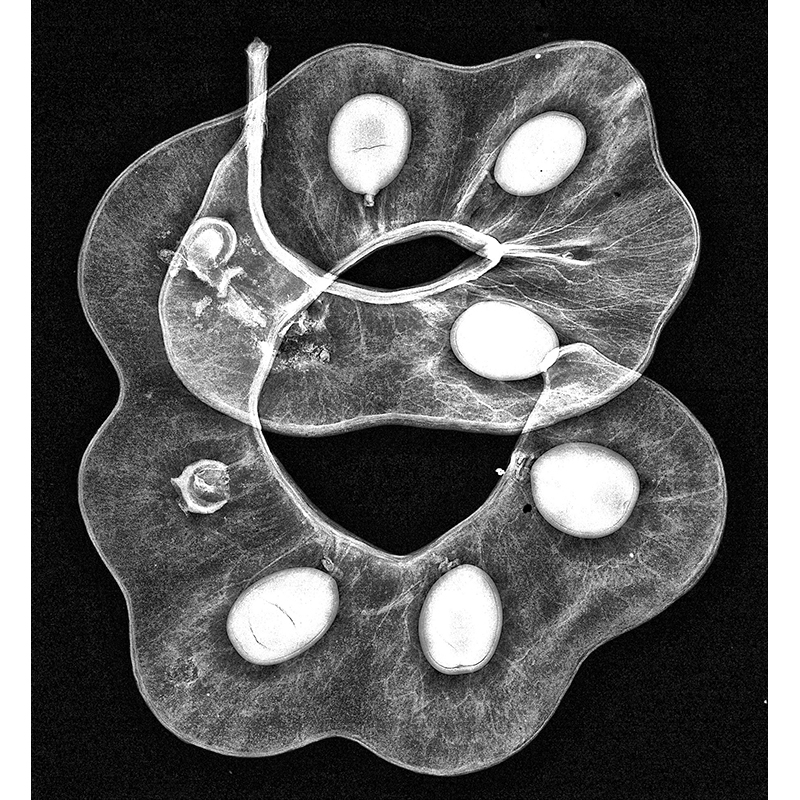

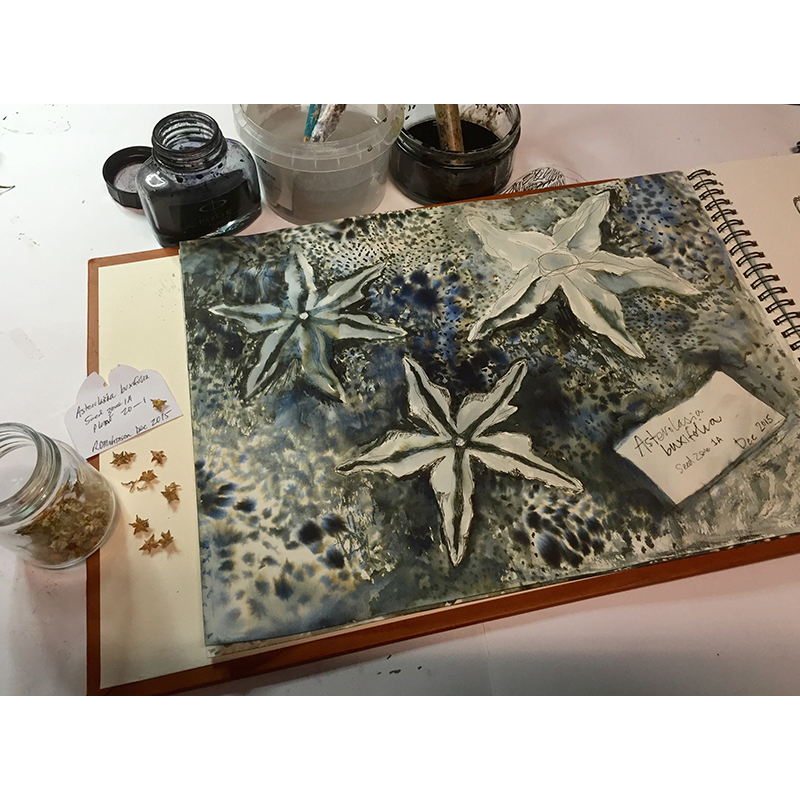

Munns has dedicated much of the last decade to this exploration of agricultural diversity. Her current project—Seeds Through the Artist’s Lens—is comprised of a series of public workshops exploring and documenting seeds and other plant materials. It culminates in rotating exhibitions at the Australian Botanic Garden, and is based on her broader effort, Homage to the Seed, an inquiry into seeds as both scientific and cultural artifacts. This work includes botanical sketches in ink, felted seedpods, and photographs of archived plant material. It traverses a continuum from abstracted digitized prints, to collage in which seeds are embedded as both subject and artistic implement. Munns’s art has been shown in galleries throughout Australia, but she connects her passion with people around the world through her traveling studio, called SeedArtLab.

We are seated at a sprawling wooden table in the Garden’s seed bank, positioned in front of a well of sepia ink, large sheets of linen drawing paper, and pods and twigs to be used as both drawing implements and inspiration. Munns squints, shifting her gaze between thick, matte paper and a shiny, black seedpod collected from the Australian Botanic Garden in Mount Annan. “Art,” Munns says, “is my way of participating in the grand dialogue around seeds. Art is a bridgeway beyond fear, unknowing, and elitism. It can thrive on curiosity and open doors and windows where there were none.”

—Simran Sethi for Guernica

Guernica: The residencies and workshops you hold at botanic gardens throughout Australia have helped increase people’s understanding of the importance of seeds. What does this work mean to you?

Sophie Munns: Seeds Through An Artist’s Lens is, in part, about the art I make, but it’s also meant to be a commentary on how we see seeds—from what viewpoint culturally, politically, scientifically, collectively, and personally. I have met people for whom pruning is the greatest excitement they can have. For me, it is seeing the seeds on their journey: finding them, encountering them, learning how they come into being, and going from there.

On days when I felt the earth holding me when nothing else seemed to—I began to notice what was going on at the soil level.

Guernica: How did your personal journey lead you to seeds?

Sophie Munns: I left home at eighteen and underwent constant change in my twenties. By thirty, I settled in Melbourne and promptly unraveled. A depression gripped me at the time that, I see now, was inevitable and timely. When that depression pulled me to the ground—on days when I felt the earth holding me when nothing else seemed to—I began to notice what was going on at the soil level.

It took a year of hitting the ground, watching seasons pass and new things springing up, but, at that level, I think it was the sheer in-your-faceness of nasturtiums that clicked my brain into that most obvious of revelations. I saw the seeds of summer cast off the plants and into the soil and begin to grow again.

I quieted myself down and gave attention to my journal, books, writing—and practicing art without expectation of “what next?” Waves of fear and uncertainty would wash over me, but I was hugely productive as I cultivated this new kind of pattern for living that started as a seedling.

I was fully present, for the first time, to life cycles. What I had long known intellectually about plants coming into being, dying away—fallow periods and reemergence of plant life—was observed by me in a new and innocent, almost childlike, way until I understood the lesson that had been eluding me since my father died when I was fourteen.

After he died, I’d learned to wait for everything to just die. I expected things to die. I was more expectant of things dying and leaving than I was of things coming into fullness. The Melbourne Botanic Garden was next to my studio. I’d come out of the space for breaks and lie on the ground in the sun. That long moment of recognition that things die off but return to life in another form later, in cycles, repeated over and over and over. That garden in Melbourne waited for me—a place to undergo my own dying off and slow rebirth into an artist with a sense of calling.

I needed to learn that so deeply. I had felt my father’s death too strongly and had not known how to release the grief.

Guernica: As someone who just lost her father, this resonates; the grief is cellular.

Sophie Munns: Exactly. But those nasturtium seeds were so full of feisty narrative, their lust for life not hidden away. I slowly started to notice other plants reproducing each season, but for a rather long time the lesson of the nasturtium was the only reminder I needed. I didn’t care how disregarded they were for not being elegant or especially clever or complex. They had a life force in them that was potent enough to get my attention and wake me up.

After that, I felt a powerful, personal resonance with seeds. Like they were messengers from a very big universe that were telling me, “It’s okay. It’s a big, tough world, but you can rise up, regenerate, gather your energy, and go forth. Let your life force come through your veins.”

I found myself drawn to the work of cultivating my own garden, which, in my case, meant growing a meaningful life as an artist. That became my work. I didn’t go to yoga retreats or on spiritual programs; I laid down on the soil.

And it was, essentially, what my Homage to the Seed art series is now—without the seeds and the science and residencies. I was on a mission. I was a curious mix of fear, audacity, vision, purpose, and lack of confidence.

Guernica: Can you talk about the line between maintaining scientific integrity and honoring creative expression?

I felt that there was a need for far more intelligent debate around all things related to seeds.

Sophie Munns: I’ve tried to keep a strong focus on the various ways one can talk about the people and plant story across millennia. Genetic modification had become such a hot topic of conversation by 2010 that it seemed to have pushed the multitude of other reasons seed diversity is threatened out of sight and out of mind for many people. What I was hearing in everyday conversation was tremendously confusing. I had to do a great deal of research to not only identify all the impacts to global seed diversity, but also to glimpse how significant these less-discussed impacts might actually be. And when people who attacked me about working with “evil seed scientists” failed to ask me what I thought and what the scientists I worked with actually were doing, I started to feel something clearly wasn’t right about how the public dialogue was going. I felt that there was a need for far more intelligent debate around all things related to seeds. The scientists are conscientious, ethical, culturally sensitive, and highly focused on building projects across the planet, with the needs of particular communities addressed from the ground up.

Guernica: Is the democratization of knowledge your explicit intention?

Sophie Munns: Yes. It goes back to that whole thing about respect for learning, of sharing knowledge, of smart people being open and leading. I’m fortunate to now know some excellent scientists who want to see the important messages getting out there and are supportive of all kinds of measures to see that happen. So, yes to democratization of information and blowing apart the old elitism around knowledge of botany and horticulture.

Guernica: How has your creative process evolved? When did you first encounter the seed in your own work?

Sophie Munns: Back in 2000, I relocated from Melbourne to Newcastle in New South Wales in massive mourning after my house burned down. One year earlier, thousands of people from Newcastle—especially men who’d worked their entire lives in one job—lost their jobs in mining. Moving to New South Wales was yet another chapter in my life of steep juxtapositions: I was grieving like the town was grieving.

I had left Melbourne—a city that relished the arts, the mind, culture, books—to arrive in a place that was in need of healing after almost 170 years of heavy, dirty industry. Every day in Newcastle, it seemed, the entire town would gravitate to the beach. For nearly two centuries, it’s where people washed the coal dust out of their skin. Although it looked like a casual and easygoing way to spend a bit of the day … take a walk, a surf, stare at waves from the car, whatever; it’s a massive ritual. I saw these people washing away their sorrows from a hard life. And I saw I had to do something quite different to make my passage to a new life, too. So I went back into schools to teach and continued painting on the side. Water was the theme of my painting whilst I was in Newcastle. I looked at the symbolism and metaphors, delved into fluidity as poetry, life, cycles, change, all of that.

Then, after four years responding to water and fluidity, a motif landed in my water paintings—a seed pod form. At first, I could not identify where it had come from or why. It began taking over my studio, as I was compelled to paint this pod form and was actually very angry for a year or two because I had not consciously selected it. I didn’t want it, as I had no narrative for it.

When I got into the postgrad MFA program at Newcastle University in 2007, it was to explore the role of the artist in a time of unprecedented velocity and complexity of change. What did a humble pod form have to do with that?

I could not believe I was being shamed by someone whose art was so academic—so cerebral—that I found it to be questionable as creative expression.

Guernica: This has not been what you envisioned.

Sophie Munns: Not at all. During that aborted postgrad experience of 2007, a female art professor actually laughed at me for having created a hardcover A3 visual diary where I was working through concepts visually, in color, in text, drawing whatever related to my research abstract, one by one. I was diligently working my way through ideas, creating, if you like, a visual language to become intimate with what mattered to me to think about. This was a crucial intellectual process for me, and I could not believe I was being shamed by someone whose art was so academic—so cerebral—that I found it to be questionable as creative expression.

I was not interested in going in search of text that spoke to my key topics. I didn’t want to be in someone else’s head. I wanted to hear myself think, so I was visualizing ideas on paper; I was feeling my way into it. The academic saw that as terribly dumbed down, but, paradoxically, I saw her way of building knowledge as terribly third-hand and having nothing to do with life. I was given the impression I looked like a failure of an academic before I even got going that year.

It might have been great if I had gone to academia to learn to articulate and mention the right research and all that, but my life really started when I dropped out of academic pursuit, ended up in Brisbane, and gradually came home to a more developed version of my life’s work through walking the neighborhood and picking up seeds.

Unable to pursue formal research, I turned to my lingering seed story and ended up, by coincidence, at the Botanic Gardens in Brisbane volunteering in the Seed Lab, part of the Millennium Seedbank Project that Plantbank is also connected to.

Guernica: Has this been the greatest confirmation that you’re on the right path?

Sophie Munns: In 2010, I had some work from my seed lab residency at Brisbane Botanic Gardens in a group show. A woman in her late 60s came in who said she never looks at art and talked to me about my work. She wasn’t terribly articulate or very educated, but she completely surprised me with her reading of my work and project. She said, “Your work is not selfish. It’s amazing.” I felt deeply understood by this woman. I think she saw that this was an art whose intention was for people to wake up to the power of seeds and what they can mean for all humans. It’s not about me projecting my desires by painting things that really only refer to me and my little life. She could see it wasn’t “look at me, the artist” art.

I am driven to want to highlight, make room for, celebrate the many—and sit as far away as possible from the same old elitist position that purposely excludes for the good of only a few. I want to see something happen that is meaningful for all kinds of people; I like seeing when someone very closed has a new experience. I like seeing the change that’s possible when people wake up and realize there is something they can do.

Simran Sethi is a journalist and educator focused on food, sustainability, and social change. She is the author of Bread, Wine, Chocolate: The Slow Loss of Foods We Love (HarperCollins, 2015) and is an academic associate at the University of Melbourne’s Sustainable Society Institute In Australia.