In December 1968, American nuclear engineer William Anders was 238,900 miles from home, aboard Apollo 8, the first crewed spacecraft to reach and orbit the moon.

Anders had been tasked with documenting geology and future landing sites on the moon’s surface. But when, on Christmas Eve, he caught his first glimpse of Earth from afar, the sight compelled the astronaut to momentarily abandon the mission’s rigid photography schedule.

“Hand me that roll of color, quick, would you?” he asked fellow crew member James Lovell. His camera loaded, he aimed his lens toward that tiny globe, his home. From up there, it was as alien and as intimate as an exposed beating heart.

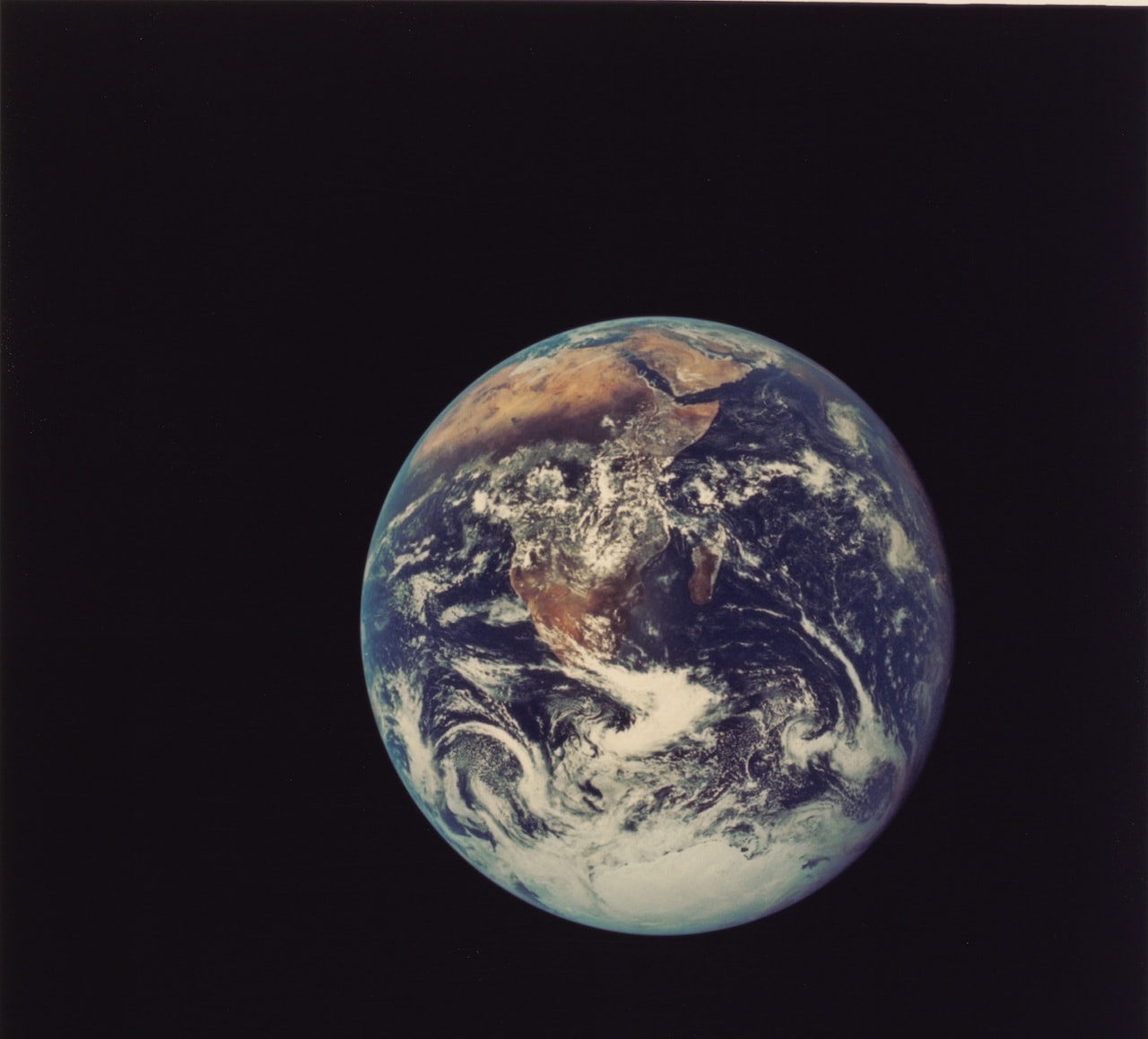

The result is Earthrise, the most famous astrophoto in history and one of the world’s most reproduced images: Earth, in color, for the first time. Partially obscured in shadow, our white and blue sphere ascends from infinite pitch blackness, with the moon’s sloping, monochromatic mass in the foreground.

Anders was experiencing something staggering when he reached for his camera, and he produced an image meant to convey an awe-struck, Earth-centric sensibility. Yet in the decades since the Apollo 8 voyage, how we envision the universe and how we understand our place in it have changed—and so, too, has the gaze with which we capture and interpret images of Earth.

Two recent astrophotography exhibitions give us an opportunity to reflect on this cultural shift. Last July, the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened Apollo’s Muse: The Moon in the Age of Photography, a celebration of astro-imagery from the past 350 years, collected to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the more-often-remembered Apollo 11 mission. The exhibition featured many lunar images (impressive, but familiar) as well as some now-renowned snapshots of astronauts. Its few images of Earth, however, were much more remarkable, and included Earthrise alongside Apollo 17’s Blue Marble—a grander and more detailed photograph taken four years later, in 1972, from only 18 thousand miles into space.

I found myself in a closed loop at the Met, shuffling between these two photographs while the gallery bustled around me. Walter Cronkite’s voice emanated from an old TV somewhere, narrating the moon landing, while other excited patrons searched for Neil Armstrong’s photo of Buzz Aldrin or James McDivitt’s photo of Ed White doing the “spacewalk.” But I found Earthrise and Blue Marble, like something obscene, equally difficult to look at and to look away from.

Compared with Armstrong’s or McDivitt’s triumphant portraits, both these photos of Earth are more elegant and more unsettling, in part because of their simplicity. Their almost operatic composition places our planet center-stage amidst a black sea—but that absolute lack of color encircling the globe drew my eye first. It appeared vacuous, even impassable. I was transfixed for a long time by that chasmic infinity we rarely observe, before I turned my focus to the Earth as Anders presented it. There was, with baffling, Russian doll-like concentricity, every single location in which humans have felt, thought, moved, lived, and died.

America awoke on Christmas morning in 1968 to find a poem on the front page of the New York Times. Archibald MacLeish recounted, in Riders on Earth Together, Brothers in Eternal Cold, two previous epochs of consciousness: the pre-Enlightenment age, in which humans saw themselves at the holy center of reality; and the modern age, in which great wars and incalculable loss rendered existence contextless and absurd. He argued that what NASA’s heroic space voyagers had just experienced—a truly macro view of Earth—ushered in a third epoch, one of planetary fraternity. Seeing ourselves from afar meant Earth’s citizens were “brothers who know now they are truly brothers,” the poet concluded.

In early January of 1969, several weeks after Earthrise was published, Richard Nixon referred to the photo in his inaugural address. In 1970, the year America launched the first “Earth Day,” Congress signed the National Environmental Policy and Clean Air acts, formed the Environmental Protection Agency, and established the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Greenpeace was founded in Vancouver, British Columbia in 1971, and by 1973, the Clean Water and Endangered Species Acts had passed in the U.S.

“Views of the Earth from space have shown us how small and fragile our home planet truly is,” Nixon said in his 1972 announcement of the Space Shuttle program. “We are learning the imperatives of universal brotherhood and global ecology, learning to think and act as guardians of one tiny blue-and-green island in the trackless oceans of the Universe.”

It makes sense that most Americans welcomed this interpretation, wanting Apollo 8’s discoveries to signal human interconnectivity. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy were both assassinated months before the mission. The year 1968 was a turning point for domestic opposition to the Vietnam War, following the failed Tet Offensive and large-scale protests across the nation. Surely it was a relief for the people of this country to step back from fearful instability and determine that international differences were relative, that all people belonged together on Earth. It was the portion of Anders’s photograph that captured our planet—not its incomputable backdrop—that captivated them from the pages of so many magazines and newspapers.

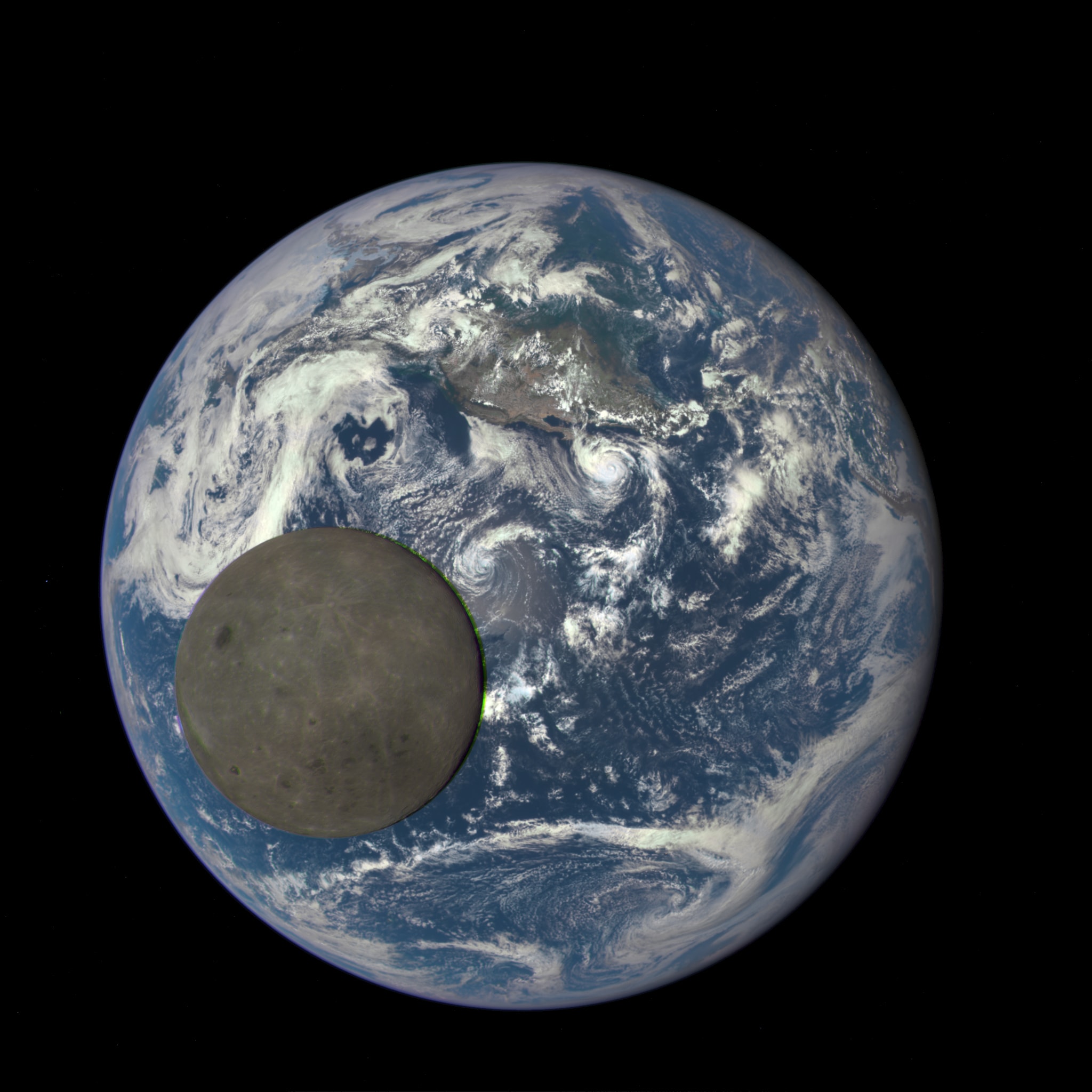

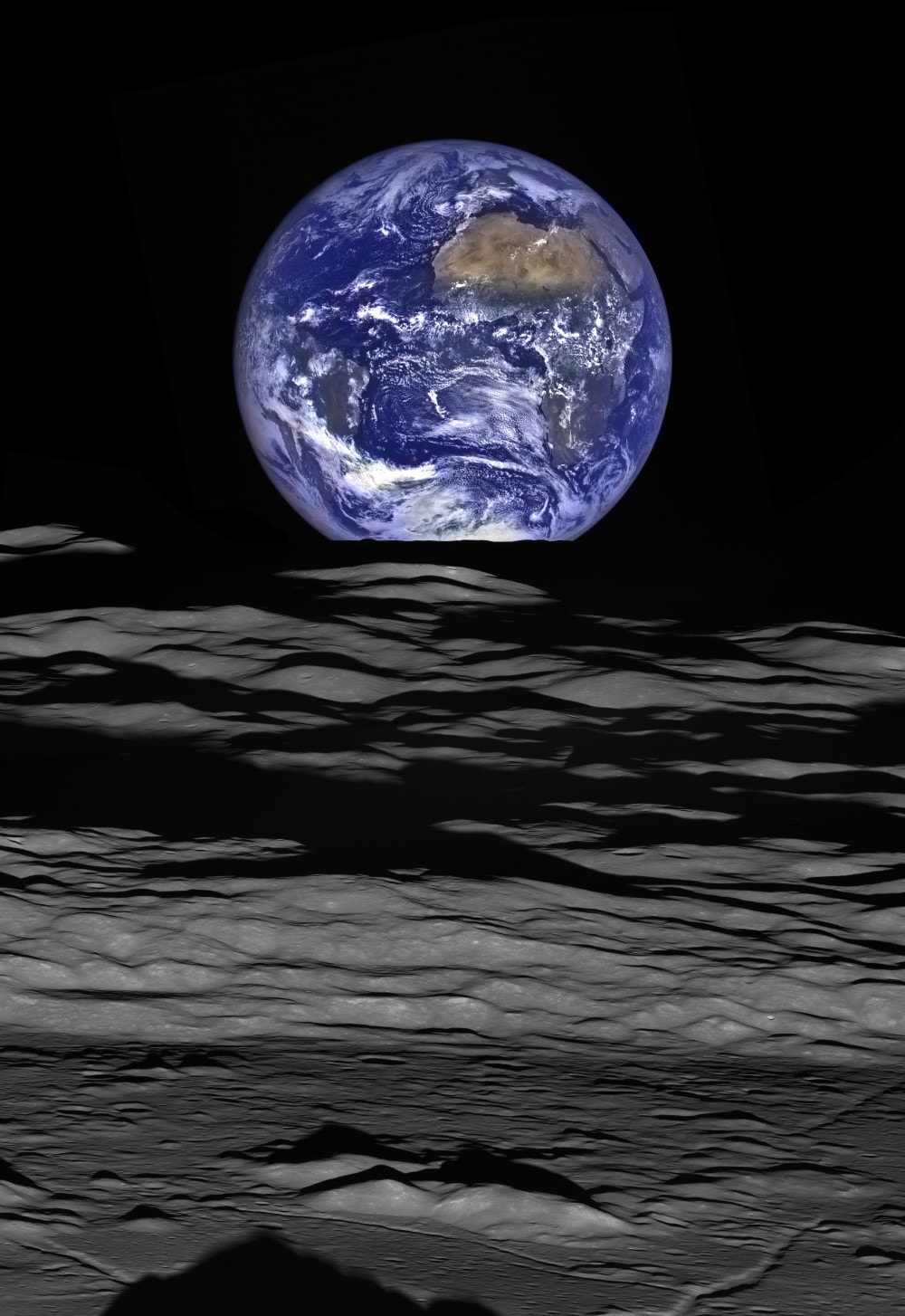

While Apollo’s Muse was running at the Met, the best remote-controlled astrophotos taken in the 2010s were on display at the Hudson River Museum in Yonkers. In this exhibit, A Century of Lunar Photography and Beyond, two images stood out for their austere clarity—the museum dubbed them Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Image of Earthset and DSCOVR Image Sequence of Moon Transiting Earth. Both were captured by satellites in 2015, and composed of several separate shots with different chromatic qualities. To achieve a depth and richness as close to human vision as possible, each is a composite of several monochrome exposures, including red, green, blue, and grayscale.

In twenty-first-century fashion, Earthset is more LED than incandescent. It was rendered by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter from the moon’s north pole and shows our planet setting, not rising. Moon Transiting Earth consists of nine frames, taken by the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR), tracking the moon as it passes in front of Earth. From the vantage of DSCOVR’s unusual halo orbit between the Earth and the sun about a million miles away, the two evenly-lit heavenly bodies look bizarrely two-dimensional, like a penny stacked on top of a quarter.

These images are the product of a series of automatic snapshots, which means there’s a remove to them. A human—perhaps grappling with an existential question—didn’t move the frame a little to the left, or postpone the moment of conception on a whim. There’s no impulse behind the camera’s perspective: these are incidental documents of astronomical locations, at given moments in time and within much larger environments.

That we are taking contemporary astrophotos this way reflects not only a change in our technology, but a change in our meaning-making: rather than illuminating our everlasting home, as Earthrise and Blue Marble once seemed to, Earthset and Moon Transiting Earth depict ours as one of many ephemeral planets. There’s something arbitrary about this new generation of photographs, a sense of transience that echoes the decentralization of Earth within our vision of the universe.

Fifty years to the day since he photographed it, William Anders wrote for the website Space.com that Earthrise “still reminds us that distance and borders and division are merely a matter of perspective. We are all linked in a joined human enterprise; we are bound to a planet we all must share.”

He certainly captured something poetic in Earthrise, with its dramatic contrast and painterly aesthetic. But looking at the photo today, I can’t help thinking that Anders’s reassessment arises from a continued urge to relieve tensions. In the half-century since he first snapped his masterpiece, wider space travel, astronomical discoveries, and globalization have expanded our cosmic imaginations. We’re dealing with similarly dire societal disasters—deadly international conflicts, famine, and climate destruction, on top of a global pandemic—but we tend to think of the universe as a much bigger place than we did in the late ‘60s, in part because we know exponentially more about it. We send robots to Mars. In the back of our minds hovers the likelihood that Earth will not always be hospitable to our vast population, and relocating to other planets in an attempt to relieve overpopulation no longer sounds like science fiction.

NASA now generates thousands of Earth images every year, with the aid of sophisticated satellites and automated digital cameras. But where people once read human belonging in photos of Earth from space, we now see a place we may eventually have to abandon. Earthrise is a notable portrait for having always contained both of these momentous elements—the joy of solidarity and the peripheral nature of human existence. Our attention has simply veered away from the known and toward the unknown.

We might, then, extend MacLeish’s lineage of self-consciousness into a fourth era. Not an era of divinity, hopelessness, or collectivity, but of coincidence. Planet Earth is beautiful, intricate, even unique, but its significance is circumstantial to both our reach and grasp. What astrophotography helps solidify is that the ways we look at and portray home dictate what home becomes. We’d never even seen Earth until the mid-twentieth century. How can we be certain we “belong” here, having glimpsed so little of our own galaxy—let alone the near-infinite regions beyond?