This past November and December, nearly 150 rusty black oil drums, splattered with drips of red paint by Nigerian artist Victor Ehikhamenor, sat stacked on top of one another at the entrance to the Jogja National Museum, as though awaiting use. Up close, each drum was marked with age, showing traces of abandonment before appropriation. Behind the drums stood an installation by Indonesian artist Maryanto Beb, composed of metal fabrications of an oilrig and its exhaust system, emitting balls of fiery fumes.

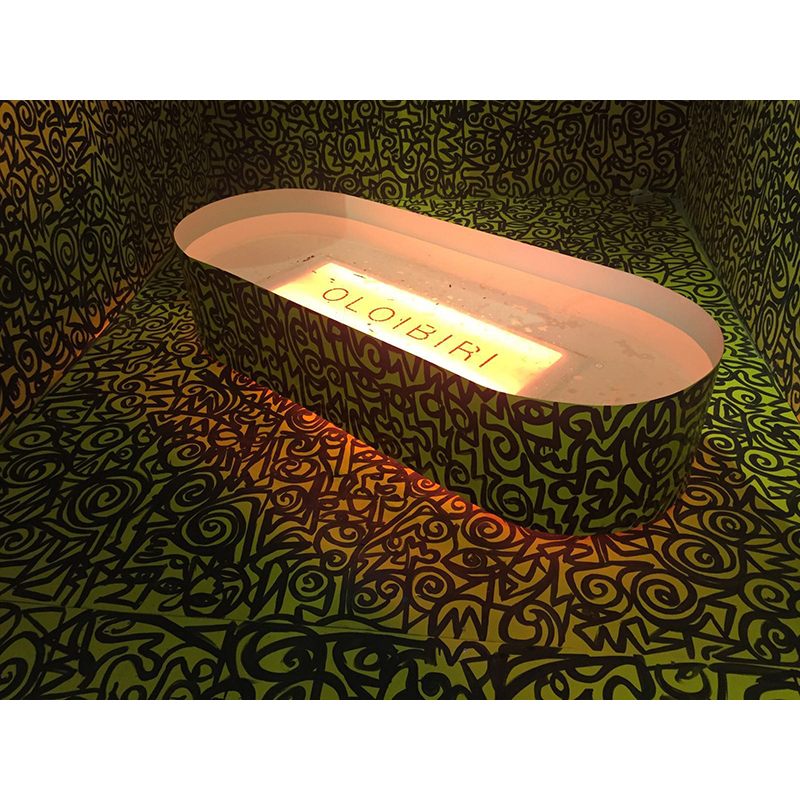

Within the museum, at the farthest end of a 20×10 room, three newer-looking drums hung suspended above a tub: two red drums painted over with black, placed on either side of a middle drum, painted white. The tub below the drums was full of water. Black liquid from the middle drum dripped into the tub, pooling around a submerged and illuminated word: Oloibiri, the site of Nigeria’s first commercial oilfield. The letters were carved sharply on a glassy rectangular surface, lit from the bottom, giving off reddish glow. After forty-eight hours of water dripping into the tub, the liquid eventually formed an outline uncannily, and unintentionally, similar to the shape of a Nigerian map—preempting a narrative of political art addressing violence and corruption in the oil industry.

They revealed something inevitably human in their formations—a shape ovoid as an eyeball, rotund as a head, and lines that intersected like hands and arms.

The walls of the room were covered in black drawings on a yellow background. The drawings, the paintings on the wall, floor, and drums were characteristically Ehikhamenor’s: the shapes and forms seemed to join without end, painstakingly linked, with the adeptness of a calligrapher.

The work in the room elicited an improbability: did the myriad shapes represent a multitude of human persons, or a community of unsightly creatures? They revealed something inevitably human in their formations—a shape ovoid as an eyeball, rotund as a head, and lines that intersected like hands and arms. Ehikhamenor is consistent in his use of these biomorphic shapes, as they repeatedly appear in his drawings and paintings. In the room, however, their scale seemed to overwhelm the viewer.

Ehikhamenor’s installations, collectively titled The Wealth of Nations, were on view at the Jogja National Museum as part of the thirteenth edition of the Biennale Jogja in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. At the Biennale, Indonesian and Nigerian artists offered interpretations of a central theme, “Hacking Conflict.” Eleven Nigerian artists—nine of whom completed a month-long residency in Jogja last October—were invited to join twenty-three Indonesian artists in the main exhibition of the Biennale. They included Segun Adefila, Aderemi Adegbite, Ndidi Dike, Emeka Udemba, Emeka Ogboh, Temitayo Ogunbiyi, Amarachi Okafor, Uche Okpa-Iroha, Kainebi Osahenye, Olanrewaju Tejuoso, and Victor Ehikhamenor.

In his curatorial essay, Jude Anogwih, the Nigerian associate curator of the Biennale, noted: “the intersection between art and…‘hacking’ within the context of BJXIII is aimed at increasing the chances of tinkering, iteration, and participation between Indonesian and Nigerian artists.” He adds: “It was paramount for me to bring together and harmonize divergent minds and practices, weave our various cultural and political narratives into one big understanding.”

Indonesia and Nigeria are both oil-producing countries, situated on the equator, with histories of colonialism and dictatorship. This shared history is the premise of The Wealth of Nations, through which Ehikhamenor triangulates Nigerian contemporary experience around oil, violence, and art. Ehikhamenor’s work in Jogja, writ large, is political. “I hope Nigerian observers reflect on the issues raised by the installation,” he told me.

The monumentalizing of national history can take many shapes. Intrinsic to The Wealth of Nations is the oil drum as Nigerian monument. Another shape is lore. These two seemingly unrelated items are occasionally intertwined. For almost two decades, from the early 1970s until the mid-1990s, the recursive Nigerian military governments made a spectacle out of the death penalty. Crowds gathered to watch famous armed robbers and coup plotters meet their end. I recall a story my mother told of the execution of an armed robber. She omitted details of location, year, or name. The robber was feared in the entire country and had evaded arrest on many occasions, but his doom came unexpectedly. The robber had been stealing from the time he was an adolescent. When his mother complained of his pilfering, his father said, “he’s only a boy, he’ll outgrow the habit.” He didn’t. On the day of his public execution, tied to a stake, awaiting the volley of bullets from the marksmen, he asked for his father. His father came. Pretending to whisper, the condemned man bit off the old man’s ear. “You could have warned me!” he cried. Those were his last words. Then the crowd—at least 30,000—watched justice unfold.

As containers for storing petroleum products, they witnessed the unevenly distributed wealth of a nation. As buffers for bullets in the past, they indicate that national violence has not been in short supply.

In the Robbery and Firearms (Special Provisions) Decree of 1970, a firing squad is prescribed as punishment for the offence of armed robbery. One prominent depiction of its application is in photographs from September 8, 1971, showing the killing of eight convicted robbers in Lagos. The notorious robber Ishola Oyenusi, pictured up-close and smiling, seems to rest his head against a metal drum. A second photograph is of seven men tied to stakes from neck to ankle, against a background of stacked drums: two men bow their heads, one appears to let out a scream, and some look directly at the soldiers poised with their rifles. In another image, three stiffened men remain tied to their stakes, lifeless. This image from the execution best shows the function of the drums: the dents on them seem to be made by speeding bullets.

Ehikhamenor’s drums highlight how Nigeria’s history is written on these objects of commerce. As containers for storing petroleum products, they reveal the unevenly distributed wealth of a nation. As buffers for bullets in the past, they indicate that national violence has not been in short supply.

In the southern Nigerian village of Udomi-Uwessan, near Benin City, where Ehikhamenor was born, the drawings he grew up seeing were ritualistic and commemorative. Chalk drawings were left on shrine walls in his village. When a child was born, the family patriarch would bring out a white chalk, make drawings in the center of his expansive compound, and say prayers. When I asked if there was a connection between The Wealth of Nations and the drawings he saw as a child, Ehikhamenor responded: “This is my foundation, a well from where everything else springs. In the village those inscriptions were communicative, not decorative, and the drawings I have deployed in my medium here are viscerally unpleasant.”

What is viscerally unpleasant about The Wealth of Nations? Is it the cumulative effect of the towering drums in front of the museum, as high as the eye can see? Or the surfeit of shapes on the walls of the room? Perhaps. But in a wider sense, presenting viscerally unpleasant artwork could refer to how Nigeria has attempted to reconcile with its past—a past in which the commercialization of crude oil is bound up with violence.

The most insidious example of this was the judicial murder of Kenule Saro-Wiwa. Saro-Wiwa, a talented, prolific, and acclaimed writer, threatened the power structure in the last decade of his life. He protested the “ecological war” in Ogoniland, his hometown, in the heart of the Niger Delta. On November 10, 1995, he was hanged for the alleged murder of pro-government Ogoni chiefs, alongside eight others, by the vicious, corrupt and insecure government of General Sani Abacha. Two days after the hangings, Shell, the multinational oil company complicit in his violent silencing, concluded a 4 billion dollar deal in Nigeria. Shell strongly denied a hand in the hangings. But they were adjudged complicit in the court of public opinion. Saro-Wiwa and his comrades, leaders of the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People, campaigned for greater autonomy, a fair share of oil revenues, and repair of the environmental destruction wrought by multinationals, especially Shell.

Twenty years after his death, a memorial sculpture by Sokari Douglas Camp in the form of a steel bus was barred entry into Nigeria. On both sides of the bus, Camp inscribed the following: “I accuse the oil companies of genocide against the Ogoni.” On the grounds of its political value, customs officials in Lagos impounded the sculpture, in addition to leaflets and reports sent by courier to commemorate Saro-Wiwa’s life and death. Does Saro-Wiwa’s activism, even in death, indict the present political class? Apparently. The ecocide that Saro-Wiwa protested, and Camp reasserted, recalls the dripping oil in Ehikhamenor’s installation, spilling into a tub—oil spillage that results in monumental hazard to the environment, devastating the lives of present and future generations of southern Nigerians.

Each empty oil drum is a loud container for the voices of Nigerians who deserve a better life. To call the work “political” is to affirm its aesthetic worth, and to position it where it matters most—in the public imaginary.

The decision of the customs officials to impound the bus, doubtless an instruction from above, points to a regretful inability to reconcile the viciousness of the past with its memorial in the present. In the consciousness of the ruling class, there are certain events that must be suppressed for the giant strides of democratic progress. (Isn’t it additionally poignant that a locomotive object indicates that Nigeria is slow to reconcile with its past?) That such suppression of history is unacceptable is evident in Camp’s steel bus, and Ehikhamenor’s oil drums. In the latter, monuments are made out of the devastation left behind in the misuse of oil wealth. Each empty oil drum is a loud container for the voices of Nigerians who deserve a better life. To call the work “political” is to affirm its aesthetic worth, and to position it where it matters most—in the public imagination.

Except in isolated cases like Camp’s, artists in post-autocratic Nigeria have largely worked without censorship by the government, although this might be changing (in mid-January, prominent artist Jelili Atiku was detained with his co-performers in connection to a performance in a suburb of Lagos). In light of this freedom, why does political art remain cogent? Ehikhamenor’s installation in Jogja was available to Nigerian viewers mainly as images shared on social media, hence addressed in part to a public other than the authorities. The ultimate goal for Nigerian artists will be to stoke, through images, the consciousness of others, to show evidence of a momentous history available for reflection in the present, ensuring that protest, however silent, is necessary.

Any artwork intended to serve the imagination of a nation must, to a certain degree, be clear in its symbolism. Camp’s “I accuse the oil companies of genocide against the Ogoni,” and Ehikhamenor’s gesture of piling hundreds of repainted drums together, are powerful enough as motifs to recall grave injustices. In the light of the artist’s background and political engagement, the gesture is also commemorative.

What do people mean when they say Nigerians forget too easily? By certain accounts, as Jeremy Weate clarifies in “Life After Oil,” a timely essay in Chimurenga on the link between culture, history, and petrodollars, forgetting is a national pastime. The strides of history—if the events since the amalgamation of Nigeria’s southern and northern protectorates by the British can be called that—are quick and alacritous. Nigeria has undergone, at the most basic level, a genocidal war, several military regimes, and corruption of incredible scale, all within a span of six decades. As Weate writes: “In Nigeria, historical opinions are set apart from each other like tectonic plates. Every now and again there is an earthquake that exposes fissures over roles in the civil war or corruption in the post-independence years, or provokes harangues over who was the worst dictator. There is nothing to be built in commemoration on land that is constantly shifting.”

But this shifting land is also a memorial site. On an institutional level, with decrepit museums, the absence of contemporary Nigerian history in university curricula, and the recycling of political office holders, national forgetting seems apparent. On the level, however, of memory—the tinkering of experience by individuals and artists—the urgent task is to contemplate how remembering occurs. It is unlikely that public consciousness is separable from past momentous occurrences, eager, as Nigerians supposedly are, to move on. The traces left by history are atmospheric, a blanketing presence, typified in Ehikhamenor’s intricate drawings in a 20×10 feet room in Jogja.

Emmanuel Iduma, a Nigerian writer and art critic, is the author of Farad

and co-editor of Gambit: Newer African Writing. He co-founded Saraba magazine, and is the managing editor of The Trans-African.

To contact Guernica or Emmanuel Iduma, please write here.