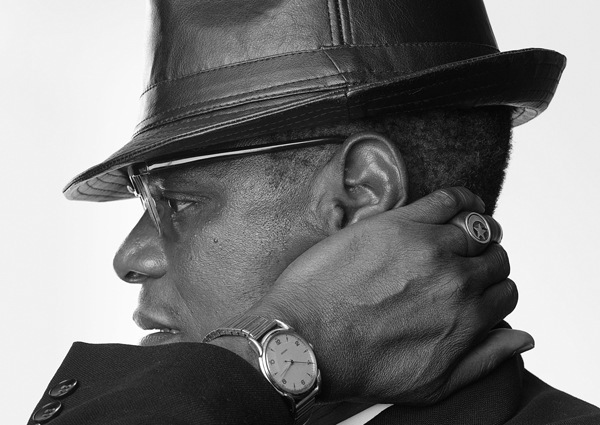

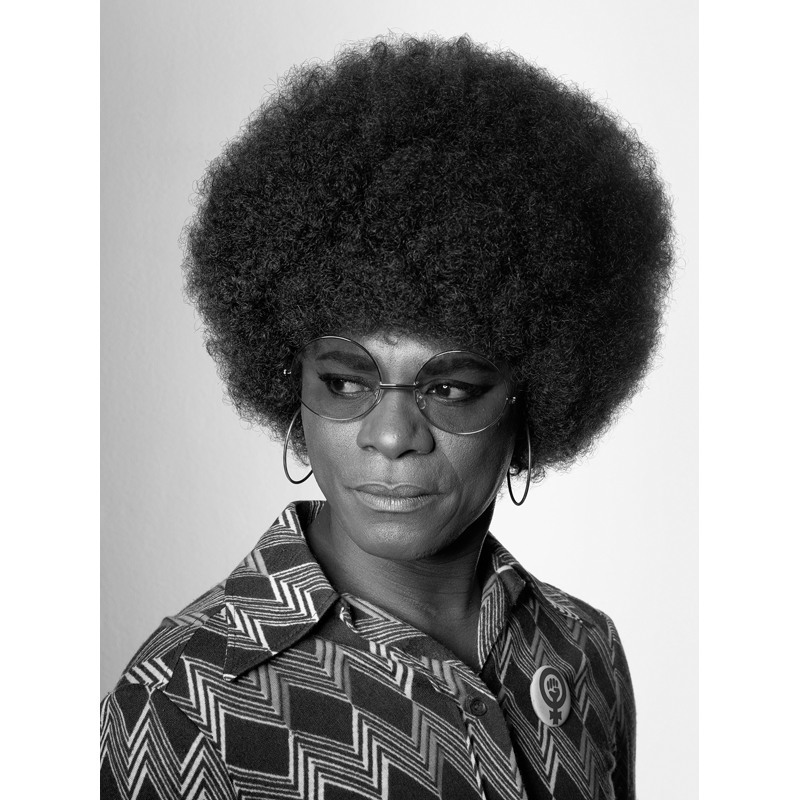

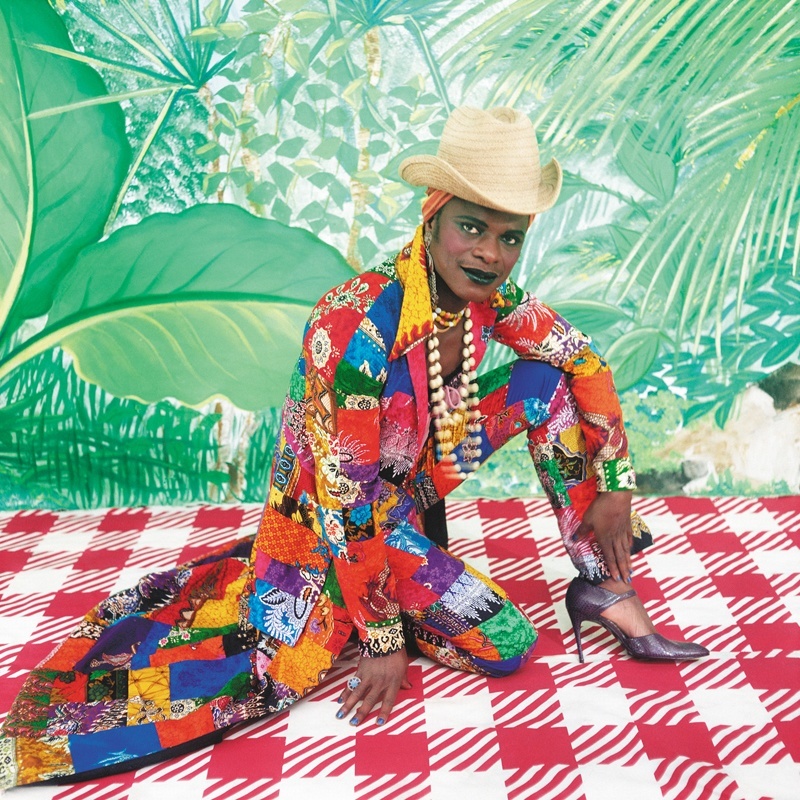

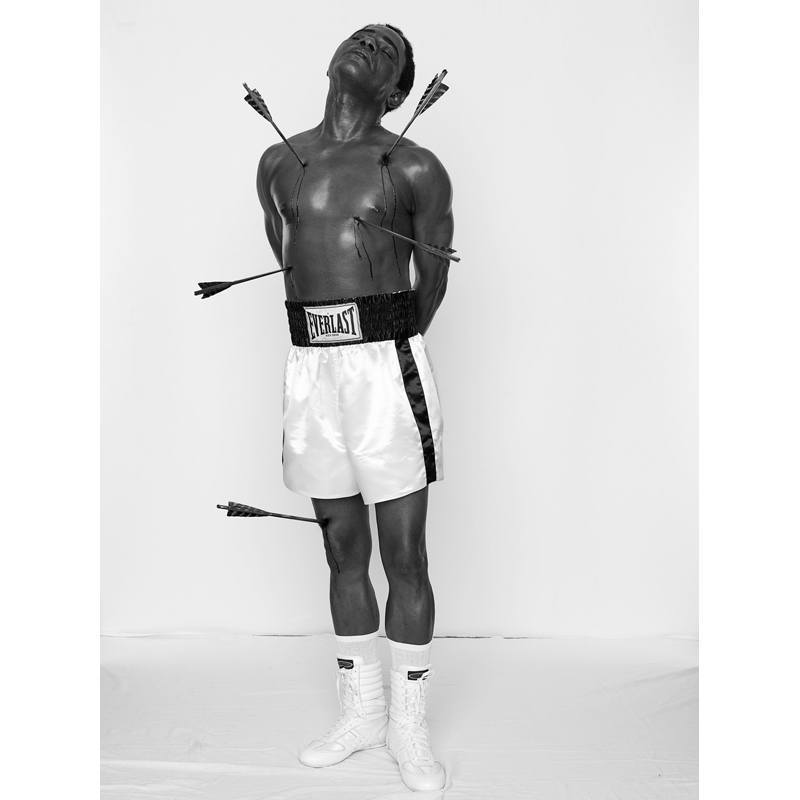

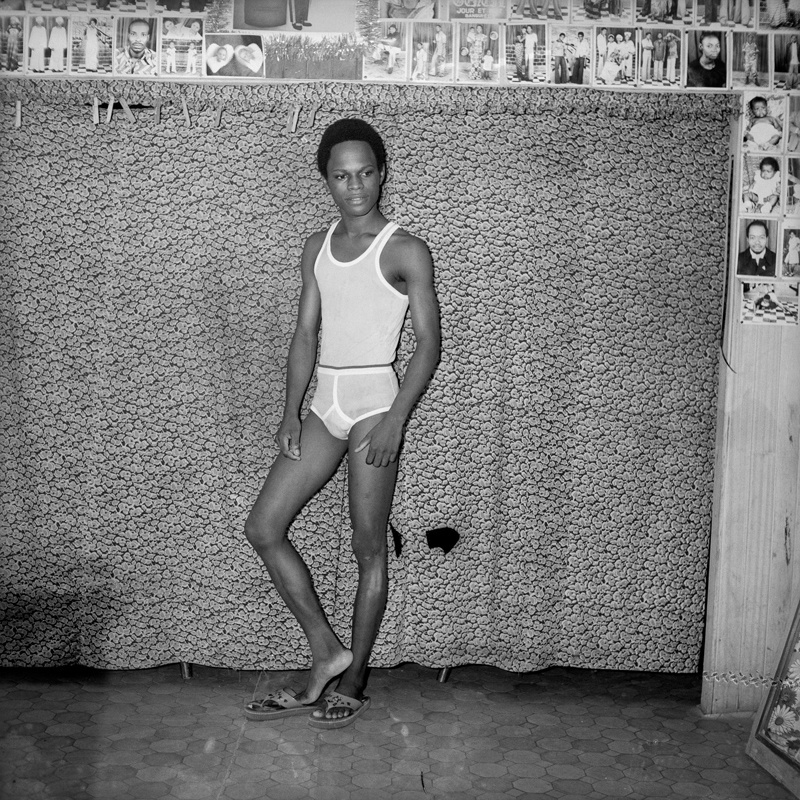

La femme liberée américaine dans les années 70, from Tati, 1997

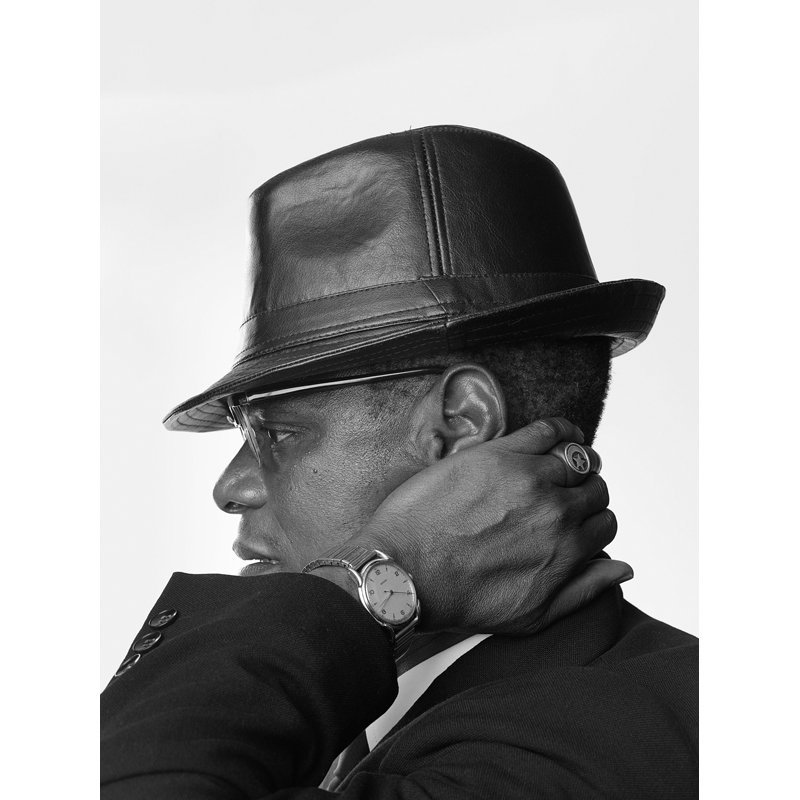

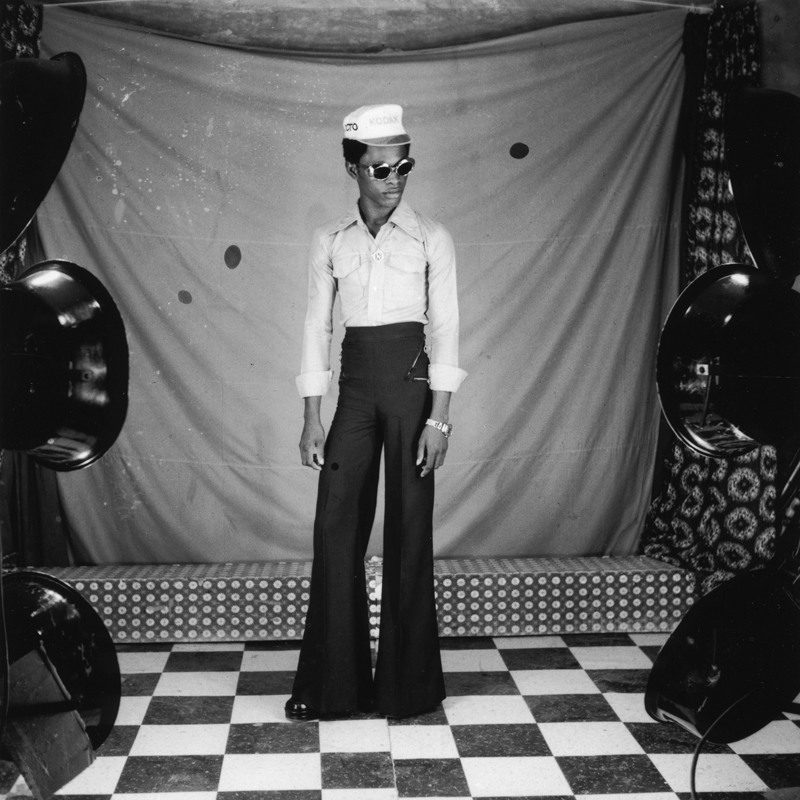

© Samuel Fosso. Courtesy The Walther Collection and Jean Marc Patras / Galerie

The self-portraits of Samuel Fosso, a Cameroonian artist, are currently being exhibited at the Walther Collection in New York. Fosso began photographing himself soon after he opened his business, Studio Photo Nationale, in 1975 in Bangui, Central African Republic, at the age of thirteen. By day, he took portraits, passport photos, and wedding photographs for paying customers. By night, he experimented with self-portraiture, examining visual identity through costume, impersonation, and performance.

Entitled Samuel Fosso, the exhibition’s unspoken premise seems to be that the artist is due for a mid-career retrospective. Established by German-American collector Artur Walther, the nonprofit Walther Collection has only been public since 2010. It opened its headquarters in Neu-Ulm, Germany, adding an outpost in New York’s Chelsea district a year later. Walther has focused primarily on collecting contemporary Asian and African photography and video art, particularly around the subject of stereotype and selfhood. This exhibition is the first in the US to combine Fosso’s past and present work in one show, with self-portraits alongside his studio work.

Split between two rooms, the images are arranged in series: Self-Portraits From the ’70s, Vintage Studio Portraits, Vintage Self-Portraits, Tati (1997), Mémoire d’un ami (2000), Le rêve de mon grand père (2003), African Spirits (2008), and The Emperor of Africa (2013). The timing is prescient: in February, news broke that Fosso’s property had been looted amid escalating violence in Bangui while he and his family were in Paris. Jerome Delay, chief photographer for the Associated Press in Africa, came across thirty years’ worth of negatives and prints strewn along a dirt road. With the assistance of colleagues and Human Rights Watch, Delay was able to frantically pile most of it into his car before escaping.

Fosso’s studio became a place where his subjects could imagine themselves untouched by repression.

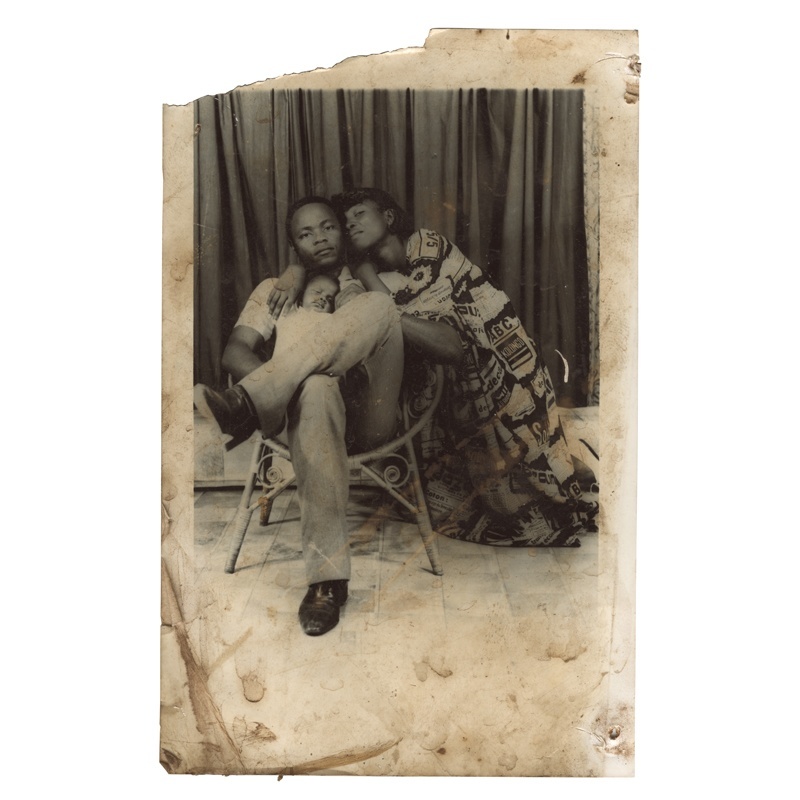

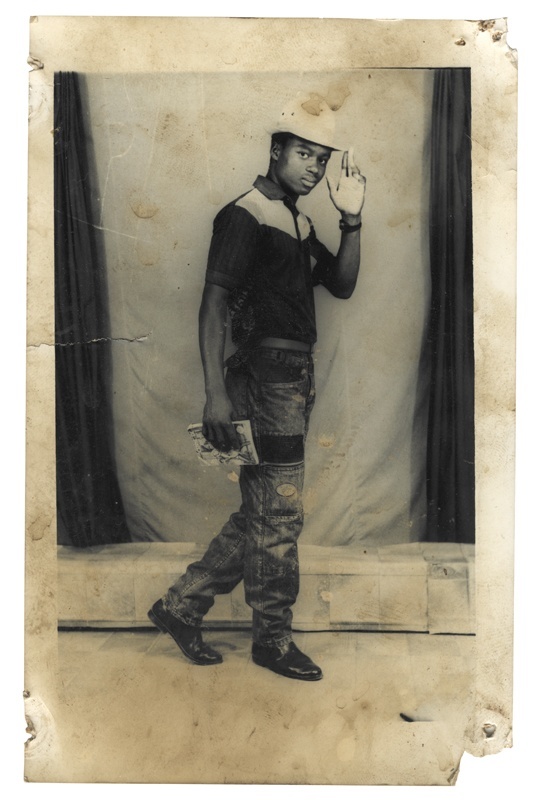

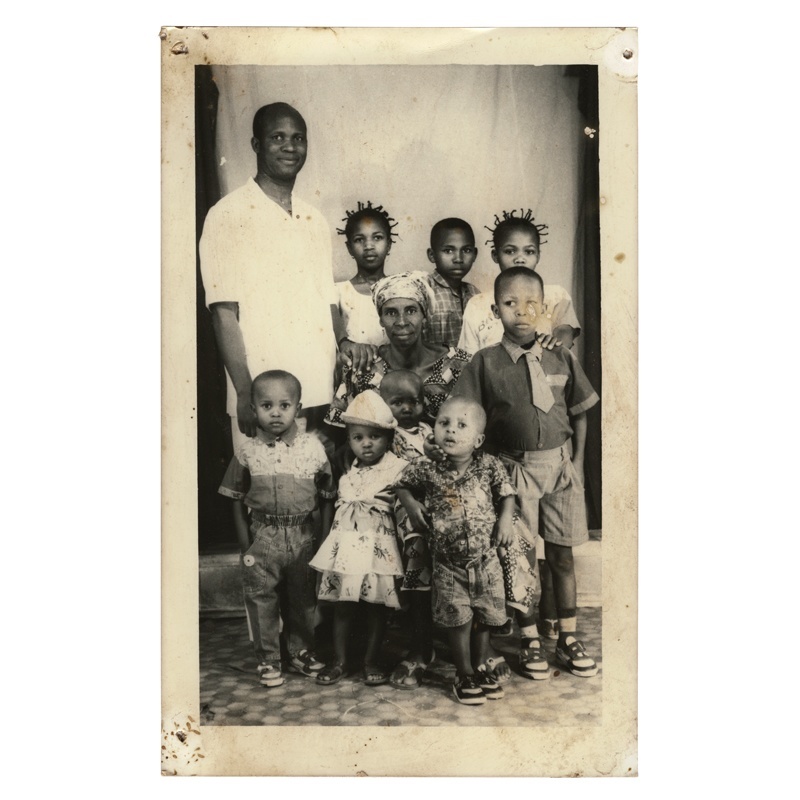

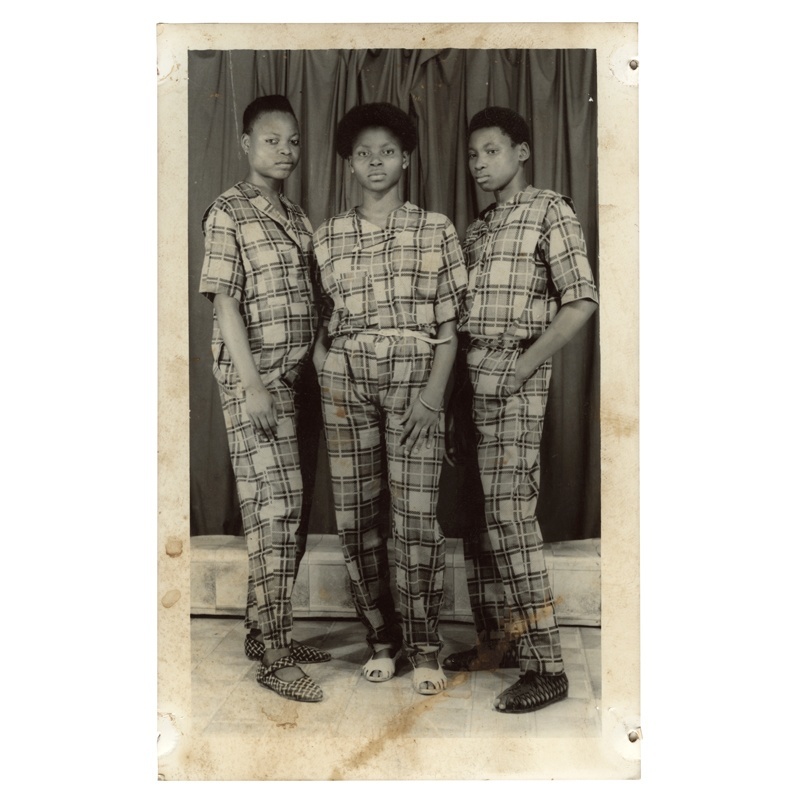

Fosso was born in 1962, in Kumba, an English-speaking town in southwestern Cameroon. His father is unknown; his mother was of the Igbo tribe in southeastern Nigeria. As a child, he was taken by his mother to Nigeria to be cured by his grandfather, a village chief and healer, of paralysis in his arms and legs. Following a miraculous recovery, Fosso stayed there, throughout the Nigerian-Biafran civil war, after which he traveled to Bangui to work with an uncle who owned a footwear factory. Laboring there as an assistant soon became tedious, and Fosso sought an escape. One day he passed by a photography studio. “I figured it was less burdensome work and that it would allow me to be more neat and orderly,” Fosso said in an interview with curator Guido Schlinkert published in 2004. This interest in orderliness was perhaps a way to stay sane in spite of the political upheaval occurring during the dictatorship of Jean-Bédel Bokassa. Fosso’s studio became a place where his subjects (a couple holding each other lovingly, three uniformed teenagers, a father and his son, a man posing with eight children and an older woman, a boy wearing a headset) could imagine themselves untouched by repression.

Fosso uses his medium differently from older-generation African photographers such as Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta. The initial drive behind the work was practical. He was bored; he wanted to avoid wasting unexposed rolls of film; and he sent the resulting images home to assure his grandmother of his well-being. He kept them to himself until 1993, when French photographer Bernard Descamps—co-founder and co-artistic director of the first African Photography Encounters festival in Bamako, Mali—was passing through town, and asked a local Kodak representative about photographers in the area. Descamps left Fosso’s studio with a stack of negatives of the self-portraits, which he then showed at the inaugural biennale the following year. Since then, Fosso’s work has been included in group shows at the Guggenheim, MoMA PS1, London’s Hayward Gallery, and France’s Centre Pompidou. The chance meeting changed his life. “It never would have crossed my mind to exhibit these photographs,” Fosso said to Schlinkert.

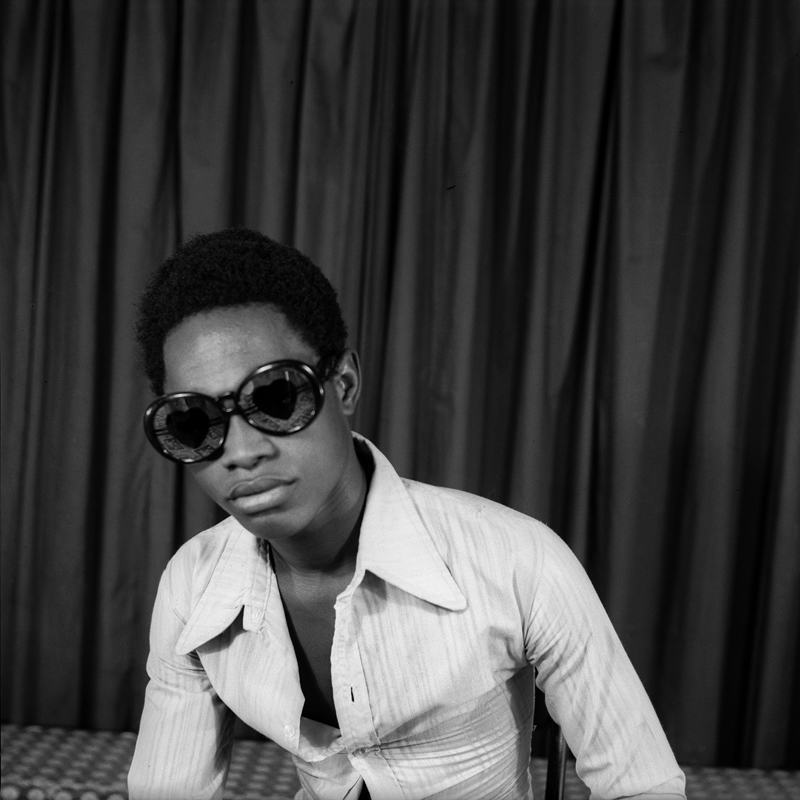

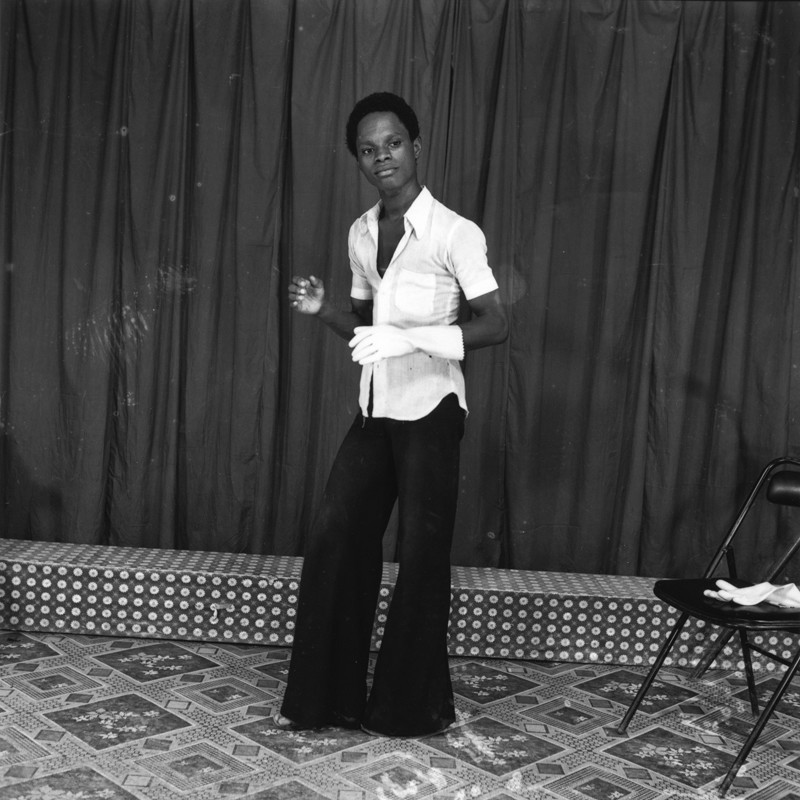

The self-portraits are intimate for what they allow to be imagined. In each, Fosso can be identified as someone other than who he is; by turning the camera on himself, his body is repossessed by another. His early work of 1976, when Fosso was only a teenager, is tempered with the swagger and vogue of that decade. He wears bellbottoms, tight shirts, and platform shoes: articles of clothing banned by the dictatorship. A sense of mild protest in his depictions of various selves continues in his later work. After his international career began, the photographs reference a moment or a figure framed by the satirical and political. The Tati series of 1997, for instance, includes “La Femme américaine libérée des années 70,” in which he becomes a liberated American woman, who, as he describes in the Schlinkert interview, is “a dream that narrates slavery, segregation, and the desire to be free, to get revenge, to be independent from whites, from men, to be economically independent, to make a career for herself.”

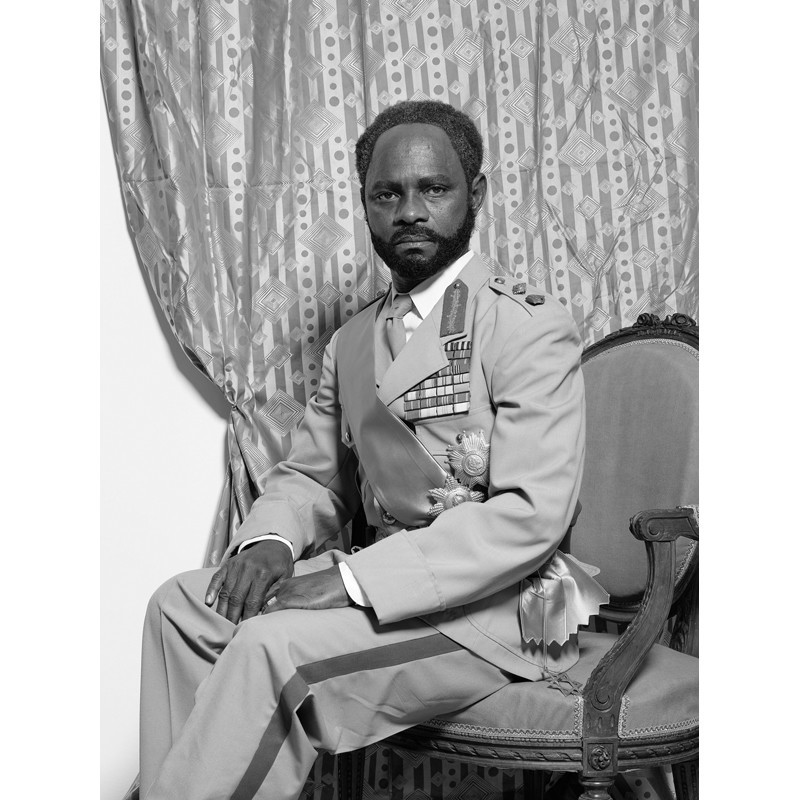

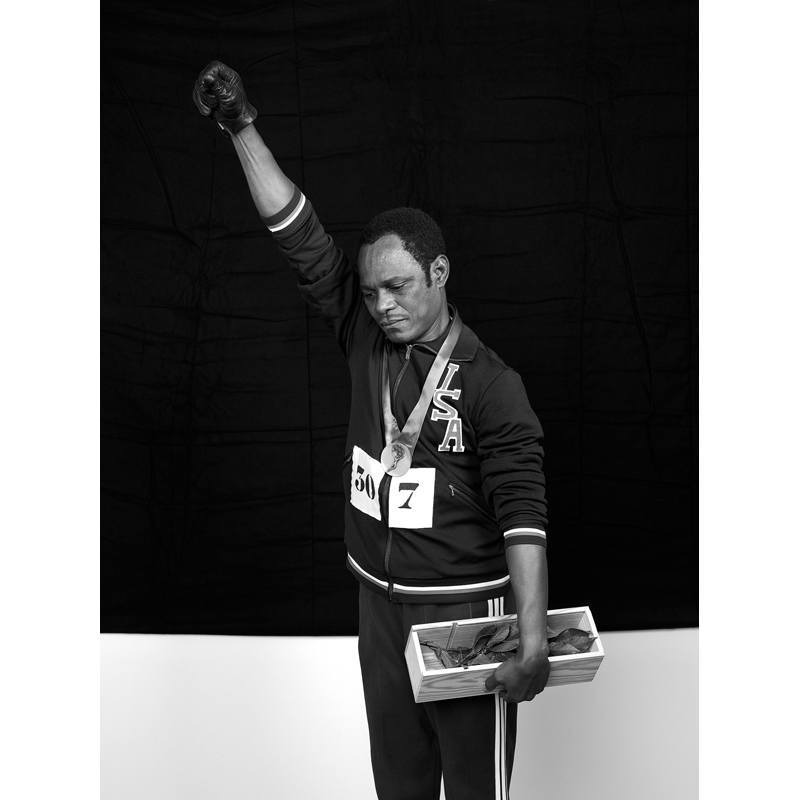

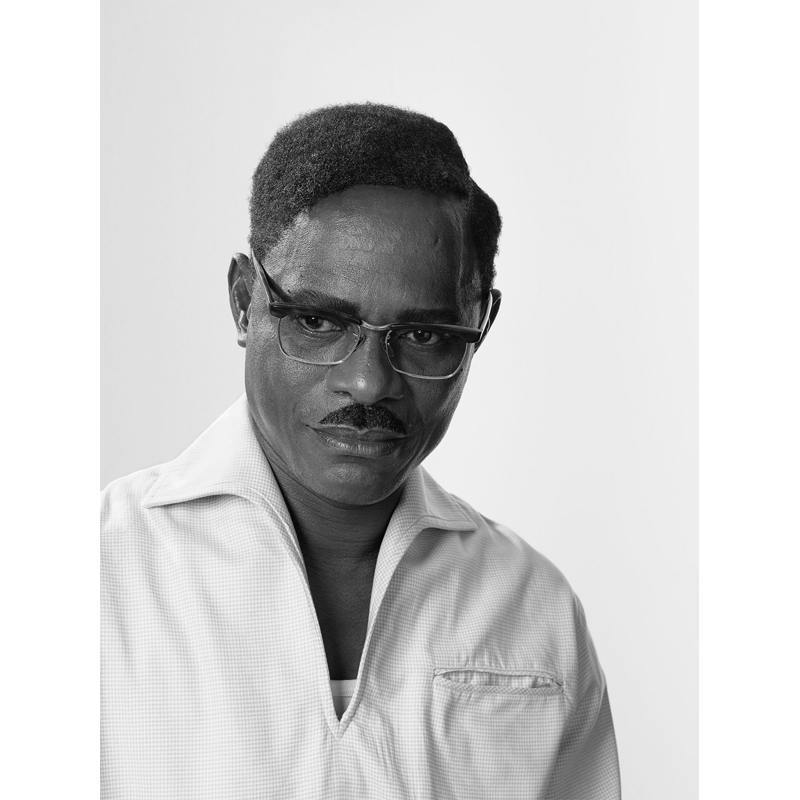

In 2008, Fosso paid tribute to historical figures such as Emperor Haile Selassie, Malcolm X, Angela Davis, Kwame Nkrumah, Aimé Césaire, Muhammed Ali, Patrice Lumumba, and Léopold Sédar Senghor by re-enacting their famous portraits. He called this series African Spirits, acknowledging that the continent stretched into its diaspora. He recognized, also, a trans-African identity, one to be appreciated irrespective of the diversities that constitute Africa. This comes as no surprise, given the earliest moments of his life spent traversing inter-African borders. In “Le rêve de mon grand père” (2003), Fosso is dressed in traditional Igbo attire, as a reincarnation of his grandfather, or in realization of an alternative career as a traditional healer and village chief, as his grandfather had wished for him.

The photographs transform self-absorption into value. “I felt, at that time, that I was handsome, young, well made, and without stain,” Fosso told the New York Times. “I wanted to have proof of this, to show my future children.” Gradually, the vanity diminished. The photographs of an older Fosso are an archive of engagement with colonial and postcolonial histories and identities. All the figures in African Spirits are replicated according to their representations in the public imagination. The rigor of this work cannot be taken for granted. It is the rigor of one who passes through fire and emerges exact and elegant. Beyond that, these representations of our favorite black heroes ask viewers to think about the use of public images, and how they become objects of worship, and of control.

Samuel Fosso at the Walther Collection in New York runs through January 17, 2015.

Emmanuel Iduma is the author of the novel Farad (Parresia Books), and co-editor of Gambit: Newer African Writing (The Mantle). He works as co-publisher of Saraba Magazine and director of research for Invisible Borders Trans-African Organization.