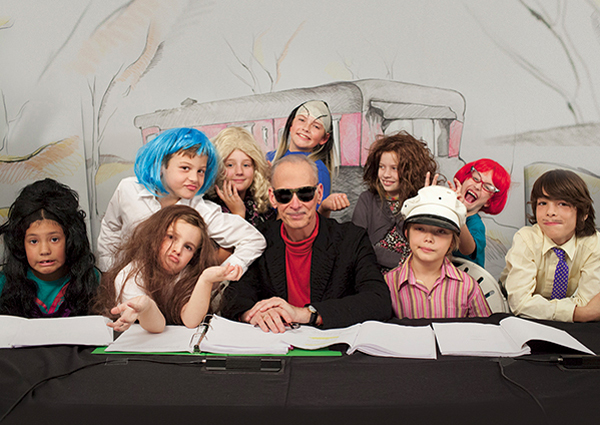

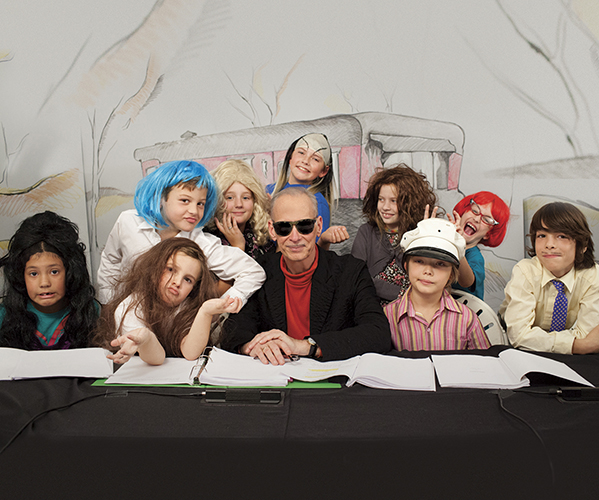

John Waters, the director of no-budget schlock masterpieces such as Pink Flamingos (1972), Female Trouble (1974), and Polyester (1981), may be the most famous underground filmmaker of all time. After Hollywood found him in the late eighties, he went on to make Hairspray (1988), which was turned into a hit Broadway musical in 2002. Through the nineties, Waters kept on making films that went against the mainstream, with Serial Mom (1994) and Pecker (1998). In the new century, the director made Cecil B. Demented (2000) and A Dirty Shame (2004). Waters hasn’t come out with a film in over ten years, unless one counts his art piece, a G-rated table-read of Pink Flamingos made with children, “Kiddie Flamingos” (2014). Waters filmed it at the request of his art dealer, Marianne Boesky, and it’s intended to be shown on a loop at galleries.

Now at sixty-nine (“an embarrassing age,” he said at a recent appearance in New York City, “I don’t even like the sex position”), John Waters seems to have a career on the upswing: he’s in development for a TV series, and he has a bestselling memoir, Carsick, the story of how he hitchhiked across America in 2012. His traveling stand-up show, This Filthy World, packs the houses on a regular basis.

Waters is infamous on TV; he regularly appears on shows such as Saturday Night Live, The Daily Show, and The Colbert Report. Those who know nothing about the director but who’ve seen him on those shows likely still appreciate Waters for his Comme des Garçons suits, and sparse, greased-back hair that’s finished off with a vaguely unsettling, dyed-black pencil-thin mustache. The TV cameras on him, he’s the talk-show guest who might say anything. On Colbert, he asked America, “Wouldn’t you rather your kid be a drug dealer than a drug addict?”

As John Waters also said during his New York appearance, “Google me and it ain’t pretty.” But much of what isn’t pretty about Waters dates from those early years when he was still America’s dirty secret. Back then, his fans had to catch his work at a midnight show or perhaps at an underground screening. His films were outrageous and unapologetically gay. They were also a respite during those spiritless years that span roughly from Nixon to Reagan.

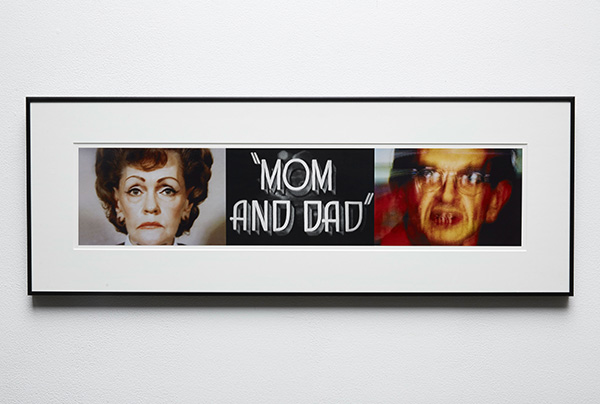

A typical Waters film set was candy-colored and cheap. His actors and crew were a ragtag ensemble Waters called his Dreamlanders. The stand-out Dreamlander was the empress of all drag queens, Divine (the nom de drag for Harris Glenn Milstead). Divine’s character was something of a horror show: she was obese and squeezed into too-tight outfits. Divine was wild-haired, unkempt, and her makeup made her resemble a kabuki demon. Other Dreamlanders included the snaggle-toothed Edith Massey, who seemed genuinely unhinged, and Mink Stole (Nancy Paine Stoll), who appeared in more Waters films than any other actor. Plotlines involved murder, rape, and gross-out comedy. A representative scene might be the one in Female Trouble where Divine gnaws through her own bloody umbilical cord—it’s often cited as one of the most compellingly gross moments ever caught on film. But, regardless of how outrageous Waters can be, any film by him is also unexpectedly uplifting. It’s as if, through them, he’s asking America for a National Conversation: What’s the worst that could happen if you let people just be themselves?

While fans might cringe at the infamous scene in which Divine eats fresh dog feces in Pink Flamingos, they’re later enlivened by lines such as this one in Female Trouble: “Queers are just better. I’d be so proud if you was a fag and had a nice beautician boyfriend.” In the seventies, that counted for enlightenment.

The years passed and being queer became more acceptable; John Waters shifted and became less obviously offensive. Adding to that, Divine, the Waters muse who would do anything and everything for a laugh, wanted to go legit. Divine dropped her mask and became Harris Milstead, a portly but respectable actor. Milstead was cast in the dysfunctional-family sitcom Married… With Children. Before the cameras rolled though, Milstead/Divine died.

Waters now owns a burial plot in the same cemetery as Milstead/Divine. He no longer produces films on miniscule funds, because he says the independent film scene is dead. He regularly pitches movies to the Hollywood suits, but nonetheless says he’s happy with how things have turned out. His books seem to have guaranteed slots on the New York Times bestseller lists. He also exhibits his art for Marianne Boesky, with whom he’s had three exhibitions, the latest, “John Waters: Beverly Hills John,” was in January of this year.

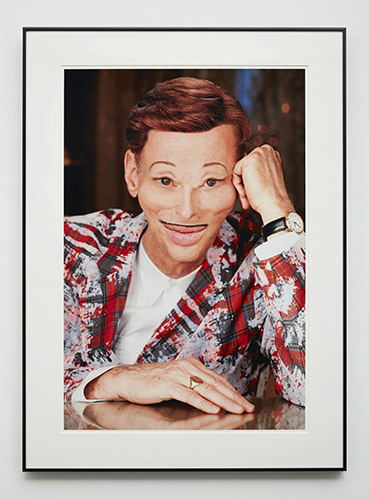

While Waters hasn’t filmed a singing anus or dog-shit-eating drag queen in years, he still upsets his various audiences. Any fan will say that he isn’t really trying to gross us out, though: Waters is just telling us something of the truth. A recent example of one of those disturbing truths comes from his art, the self-portrait “Beverly Hills John” (2012). It’s a nightmarish work, a Photoshopped rendition of the filmmaker looking tanned and serene, but surgically altered and seemingly melted by the West Coast sun. It’s a vision of what the director might have looked like if he had gone down the Hollywood path—instead of the one he chose in Baltimore, Maryland, where all his films are set.

The man who maintains homes in New York and San Francisco still considers Baltimore his homebase. Maryland is where he grew up, and Baltimore is where he gathered his Dreamlanders. It’s where he developed his career—and it’s where his earliest, and perhaps most dedicated, supporters are located. But Baltimore is also where protests in April turned violent. At the time of his phone interview with Guernica, the riots had occurred too recently for him to have formed a clear position. “I think it’s still evolving,” he said. He was chatty and friendly in the Southern border state sort of way that defines Maryland, but seemed to feel he wasn’t qualified to comment because he was too rich and too white. As he said at the time, the neighborhoods of Baltimore are “like separate countries—and I haven’t crossed the border, yet.”

A few weeks later, while on book tour for Carsick, Waters told a New York City audience, “The problem in Baltimore is that there are an equal number of poor white people. I really wish that they would team up, the two of them. The poor people of Baltimore need to make it a class issue, not a race issue.” Waters couldn’t comment further, because, as he explained to the crowd, “I was out of town shooting a cameo for the upcoming Alvin and the Chipmunks movie.”

—Meakin Armstrong for Guernica

Guernica: In many of your past interviews, someone often starts off by calling you “statesman” or something similar, and you reject it.

John Waters: Oh, I don’t reject it; I’m flattered when they say it. But I’m modest—I just say, “Oh no…” I like “People’s Pervert.” I got it recently and it made me laugh. “The Pope of Trash” is worn out—but William Burroughs said it, so it’s a lifelong title. I used to call myself a “Filth Elder,” which sounds vaguely religious, but “The People’s Pervert” sounds very much up to the times. In these revolutionary times, I could be “The People’s Pervert.” The very first title was “The Prince of Puke,” and that came when Brenda Richardson at the Baltimore Museum gave me a retrospective of my films. This was even before I made Hairspray, so it was years ago. People in Baltimore went crazy. The Baltimore Sun did an editorial on me, pro and con. So “The Prince of Puke” became my first title. Then I had “The Duke of Dirt.” Then “The Anal Ambassador.” I had “The Ayatollah of Assholes.” But William Burroughs called me “The Pope of Trash” and that one stuck. I think “Pope of Trash” makes people think of me sitting on a throne in my house with the Imperial margarine crown on my head like Bess Myerson in The Big Payoff.

I don’t think Pink Flamingos is my best movie, but I don’t think anybody saw it and then started scarfing down dog shit.

Guernica: When people tell you stories about when they first saw your movies or the effect that you had on them, what is the usual story? Like: I saw Pink Flamingos when I was thirteen.

John Waters: Which is probably illegal. After I do my spoken-word shows, I usually have a signing, so I’m very in touch with my audience; I meet them and do pictures and they buy books. It’s completely changed over the years. It used to be “My parents called the police when they found your movies.”

Guernica: And now?

John Waters: It’s either “My parents showed me your movies,” or the parents come in with their really angry children in a last-ditch effort to bond with them by going to see me together—which is kind of touching.

Guernica: So taste has changed?

John Waters: I think so. People now have tattoos—I’ve seen so many different elaborate tattoos of all the Dreamland stars. It’s very flattering. People have gotten married, or had their first date with Pink Flamingos—and so it’s moving to me. They all seem to have turned out fine. Well, at least they’re fine enough when they come to see me. I don’t know what happens when I leave. I don’t think I had a bad influence on anybody. I made people feel better about themselves. I don’t think Pink Flamingos is my best movie, but I don’t think anybody saw it and then started scarfing down dog shit.

Guernica: What would it be like to make a movie like Pink Flamingos or Polyester or Female Trouble now, in the era of gay marriage?

John Waters: It was shocking that lesbians were buying children, and that sort of stuff. But now: lesbians have more children than the Catholics. The only thing is they didn’t go out and buy them off somebody who stole babies from kidnapped women they’d impregnated. Although, who knows. Where do all those adoptions come from?

Guernica: So your films stand the test of time?

John Waters: I think they still work somehow. There are certain things—I mean you look at some of my older movies, and there was a joke in Multiple Maniacs (1970) where somebody’s selling a hamburger for a dollar, and that was an expensive, ludicrous thing—so inflation hit some of the jokes. But still, I think they work. And if you like one of my movies, you’ll say it’s “raw.” If you don’t like it, you’ll say it’s “amateurish.” They mean the same thing. Cecil B. DeMented I think I says it best—there’s a line, “Technique is nothing more than failed style.”

Guernica: And if you made Pink Flamingos today?

John Waters: A kid could make Pink Flamingos on their cell phone today. And the difference is, the studios are looking for that movie. They were definitely not looking for that movie when I made it. You could go to film school today and make Pink Flamingos. You certainly could not when I went. So, things are better but also worse, because there’s no such thing as independent film, now. You should go into television if you want a career.

Guernica: So you think people can still—if somebody is out there with a cell phone—do something shocking, even though there’s porn out there?

John Waters: Porn is old hat. And if you’re trying to be shocking, it isn’t good. That’s why many hundred-million-dollar Hollywood comedies aren’t any good. They’re trying to shock you. It’s almost like I had a bad influence on them. But some of them I like. I’m not saying you can’t have a really great hundred-million-dollar movie—I mean, The Hangover was great—but if you’re just trying to be shocking, then you’re trying too hard. That doesn’t work today.

Guernica: So what does a new filmmaker do?

John Waters: You have to think of a new way to completely surprise people who think they’re hip. I always said you could make an NC-17 movie with no sex and no violence. Now I don’t know what that could possibly be, but if you could think it up, you’d have a hit.

Guernica: You mentioned you didn’t think Pink Flamingos was your best movie. What is your best movie?

John Waters: Serial Mom.

Guernica: With Kathleen Turner.

John Waters: Maybe, maybe. I mean, my mother always said that. You know, they’re all me. My most defining movie I think is Female Trouble—but Serial Mom is the only movie I made where we had enough money. And I think it was the best for putting Hollywood and Dreamland together. We had Kathleen Turner and Mink Stole.

Guernica: You mentioned in your new book, Carsick, that you wouldn’t make a movie for under ten million now.

John Waters: It’s not that I wouldn’t—it’s that I couldn’t. Because what they want is movie stars. I’m not going to go ask movie stars to work for nothing. I’ve made nineteen movies, I have three homes, what am I going to say to them? “I don’t have any money”? And I’m not going to beg in public. To me, you know, I’ve made all these movies, they’re out there, they’re easy to get. Maybe I’m not going to make another movie. It isn’t the end of the world. It’s not like I haven’t spoken. I think it’s very easy to get my films; I think I was understood right from the beginning. And my books do great. So as long as I have a way to tell you another story—and I’m working on a TV project right now that I’m not allowed to talk about—but maybe it’ll be on TV. TV’s better today—there’s just way more people. So, who knows what’s going to happen? I always have a way to tell stories. That’s the only thing I can pass on: always have a backup career that is equally as important to you. Nothing lasts forever.

Hollywood isn’t awful. I don’t have any complaints about Hollywood. It’s just this: the more money they give you, the more opinions they’re going to have.

Guernica: Good advice. But do you feel it would be in bad taste for you to do a Kickstarter?

John Waters: Yes. I could sell one of my homes and get a million dollars. Why should I ask poor people to give me money?

Guernica: Very good of you.

John Waters: Well, no, it’s not good of me, I probably could maybe do it, and it would be great, and the people would be great—but I already did that. I begged all sorts of people for money. I now want to go to a studio where people produce movies in a traditional way, and if not, I like writing books just as much as I like making movies. And I’m not going to be a full underground filmmaker at seventy. I’m not angry enough.

Guernica: So anger was part of your drive?

John Waters: Sure. I’ve said that forever: if you’re twenty years old and you’re not angry there’s something the matter with you, and if you’re angry and you’re seventy you’re an asshole.

Guernica: What is pitching your work to the Hollywood “suits” like for you?

John Waters: It’s completely fine. I’ve been pitching forever. Every movie from Cry-Baby (1990) on, I got a development deal with a Hollywood studio—they paid me to write it. So I’m used to the process. I do stand-up comedy, so I’m not bad at pitching. I know how to do it and I’m always very prepared. And I never go to do a pitch unless I’ve completely thought through the whole project. Hollywood isn’t awful. I don’t have any complaints about Hollywood. It’s just this: the more money they give you, the more opinions they’re going to have. That’s the math of show business. If you don’t want anybody telling you what to do, then go make a movie on your cell phone. The more money you get, the more people you’re going to have to listen to.

Guernica: And when you were pitching your idea for “Kiddie Flamingos”?

John Waters: That was not a movie. That, to me, is an art project—I did not have to pitch that. My art dealer Marianne Boesky wanted to do it—but I would not consider it to be part of my filmography. It’s a part of my art world life. And that is, some would say, a video art piece. It should never be shown in a theater. It should be on a loop in an art gallery.

Guernica: How did you pitch “Kiddie Flamingos” to the parents of the child actors? Did you say, “I’m reworking Pink Flamingos—but don’t worry, it’s family friendly”?

John Waters: I didn’t have to pitch it. The kids came from friends of people who worked for me. It was a G-rated thing and there wasn’t one dirty thing in it. That’s why it works: the kids who were in “Kiddie Flamingos”—they didn’t know there was weird stuff in it. Now, the audience knows—Oh, no, these kids are not gonna say that… But the kids say other things. It makes you feel especially perverse. It’s the only way I could react to the fad of being gross. Go the other way: become your censor.

Guernica: How were the kids to work with?

John Waters: They were great—I mean, I had this one scene, where in the original maybe Divine and Crackers were, like, licking all the furniture and stuff. And in this, I just had them kissing it. One kid was doing it and he just looked at me and said, “But why?” [laughs] Which really was a very good question.

Guernica: That fits in with your idea for an NC-17 film. That there needs to be a film without sex.

John Waters: That’s what this was. It didn’t have violence either.

Guernica: Your artwork certainly does disturb. A woman saw a printout of your artwork in the copy machine today, and she ran away.

John Waters: What piece was it?

Guernica: It was the image of Lassie with plastic surgery.

John Waters: Oh, with the face-lift. She ran away from that? Good thing she didn’t look at the picture of the Three Stooges with an imagined anal operation.

Guernica: The one that shook me was Grim Reaper, with John F. Kennedy getting off Air Force One, with Death from The Seventh Seal following—

John Waters: Well, wasn’t Bergman’s death following Kennedy? I was a fan of the Kennedys, so it was a logical step to imagine Bergman’s death haunting Kennedy as he got off that plane.

Guernica: Separate but Equal—the black-and-white photograph of a man drinking from a “Gay Single” fountain rather than a “Gay Married” one also threw me.

John Waters: That’s a famous picture; you know, it originally said “Colored.” Today, aren’t gay men my age—who can now legally marry but choose not to—aren’t they the new pariahs of the gay community? Are we going to be the most despised minority within our own minority? I’m always wondering about that kind of question.

Guernica: So it’s really about the gay community. Not the oppression of gays by the straight community.

John Waters: Correct, yes. I have different woes than my parents had.

Guernica: What’s it going to be like when gay people can get married all over the world?

John Waters: I talk about this in my show. Yes, it’s great that you can get married—I campaigned in Maryland with the governor for gay marriage and we won—but you don’t have to. In California, people are getting married, people are getting divorced. It’s a gold digger, hustler free-for-all! There’s also now gay alimony.

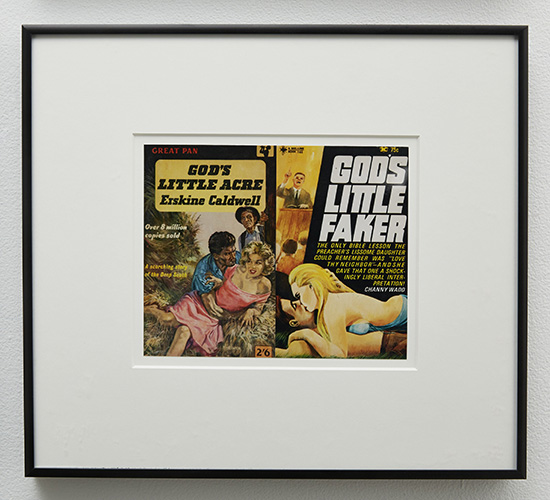

Guernica: What are your artistic rejects like?

John Waters: Everything I do, I have to write. Like, every idea for the art show, I think of the concept before I go find the pictures to make that concept real. So, they’re written too. There are plenty that don’t work. I don’t know if it’s up to me to say what my artwork is—it’s about editing, really, it’s putting different pieces or collaging from others people’s work into totally different meaning, if it’s successful. So I have many folders with backgrounds and they end up in another piece way later, twenty years later. I have many envelopes that say “Old Ideas.” They’re the ones that didn’t work.

Guernica: When you were hitchhiking, what were you after?

John Waters: What was I after? A book contract [laughs]. No, I would hitchhike my whole life. I was expected to hitchhike home from Catholic school and private school. It was not thought of as a bad thing by my parents, oddly enough—or any of the parents [of the kids] I went to school with. And then I hitchhiked during my hippie years all the time and then as an adult in my sixties I hitchhiked in Provincetown because I didn’t have a sticker, and you had to have a sticker. And that’s where I started thinking about hitchhiking again. And those were my training wheels. And then in San Francisco, I took the bus everywhere, and that was training wheels for hitchhiking too. So that’s what gave me the idea to do it. And what I was after was to give up my schedule, my control, everything. I have a calendar for the next two years. I’m scheduled. So basically, I wanted to give that up. Because I didn’t know how long it was going to take. I gave myself two weeks, but it only took eleven days. There were times in Ohio when I thought, “This is going to take a year,” because I’d stand there for ten hours, so what I was after was a mid-life crisis, basically. Instead of buying a sports car, I hitchhiked across America. And I think I got much better street cred.

Is it that horrible that someone wants to take your picture? They’re not asking you to change their flat.

Guernica: You certainly did. Everyone was talking about your adventure.

John Waters: I’m still shocked, to be honest, when I look back on that now. And still, when I go on the highway and I’m by the entrance ramp, I’m scoping them out and thinking, “That’d be a good one,” or I see a rest area and I think, “That’d be a good one.” But I’m still shocked I did it.

Guernica: In your book, you mention how you’re treated better when people recognize you.

John Waters: Well, they don’t always treat me badly if they don’t recognize me. I don’t mind if I’m treated badly across the board, but if I’m treated badly and then they recognize me because I’m famous—and then they get nice? That’s when I really hate them. The other people I hate are—they don’t know who I am, but because someone else took out a cell phone, now they want to, too! Why do you even want a picture? But I pose for pictures, of course—why would I be mean to the people who like my work? But the ones who ask you to pose with them and they don’t even know who I am, I find ludicrous. Only in America does that happen.

Guernica: Do you ever walk around in disguise? I’ve seen you on the street in New York City, but do you ever try to hide who you are?

John Waters: Oh no, because then you really look like an asshole. People think, “You’re not that famous.” I’ve seen Brad Pitt walk around. You don’t have to go in disguise. If you want to go out and be unrecognized, you can. You just go in a plain, shitty car. You don’t have bodyguards. You don’t have drivers. You don’t go have lunch at the Ivy. You go to places where paparazzi aren’t. No matter how famous you are—even Justin Bieber, but he might have trouble right now. I remember when Johnny Depp couldn’t go out. But Brad Pitt goes out all the time—and I think he handles being famous really well. He just goes out. They get used to you. I had a producer who used to say that all the time: “That’s a high-class problem.” Is it that horrible that someone wants to take your picture? They’re not asking you to change their flat. And I think also—and I’m paraphrasing Gore Vidal, which I should never do—it’s terrible when people recognize you, but it’s much worse when they stop.

Guernica: Do you think there’s such a thing as “gay” bad taste and “straight” bad taste?

John Waters: Oh, I think there’s both, yes. Gay bad taste is that squirming clichéd gay behavior that almost makes gay people homophobic. I mean the English haven’t especially used “gay shame,” but they even have Gay Shame Day, which is where they mock traditional gay culture. It’s hard for me not to join up on that.

Guernica: And that would be good bad taste? Gay Shame Day, fighting assimilation?

John Waters: Yes, I think it is good bad taste. Because I believe gay is not enough. I mean, it’s an okay start, but it’s not enough anymore. There are really some bad gay movies. I always say we got enough—we got enough gay people, we don’t need you. What’s fascinating to me is that in rich-kid schools, it’s better to be gay. No one is discriminated against because they’re gay in a rich-kid school. But in poor-kid schools, it’s often not the same. So being gay is a class issue now.

Guernica: So being gay is fine for the rich.

John Waters: Sure. Are you kidding, at NYU there’s “gay by May.”

Guernica: And straight good bad taste? What is that?

John Waters: People who want to act rich when they’re upper-middle class. They try too hard.

Guernica: So that’s bad bad taste?

John Waters: There’s bad hetero taste, which is just bad. There’s bad gay taste. Good hetero taste is the kind that never brags. And good gay taste is, like, totally being against separatism. And never using it as an excuse for anything. Why would you want to go to a gay bar, even? To me, I don’t think young people do, really because they just want to hang around the cool people, no matter what their sexuality is, and that to me is way more interesting. When you can’t tell and it doesn’t even matter, really. All the gay people I would ever be interested in are in hipster bars more than gay bars.

Guernica: You like hipsters?

John Waters: I love hipsters! Yes, I think they’re hilarious. The really cute ones try to look ugly just to prove “I can’t be ugly.” Normcore was kind of funny too.

Guernica: What do you think about porn? You also introduced porn for the Playboy Channel, right?

John Waters: I did. That was vintage porn, it was classical porn. And I must say that today, heterosexual porn is obscene. I went into a porn shop in New York recently and I was shocked at the rape and scat. I thought, Oh, my God. But, you know, that’s what we have to put up with for the freedom of bad taste. But gay porn—you feel like they’re in on it; it doesn’t seem as tragic as some poor girl getting gang-raped by forty people.

Guernica: The tragedy is what makes the straight porn obscene?

John Waters: The tragedy—it’s not my tragedy, maybe they like it, I don’t know, I’m sure there’s such a thing as a happy porn star—but yes.

Guernica: You said your life is so planned out. What is your usual day like?

John Waters: Well, I’m writing a script, so I work on that every morning from 8 to 12. And then I did an interview at noon. I’m doing this one at 3 p.m. I had two meetings about my Christmas card, I’m having dinner with my cousin who I haven’t seen in a long time. I met with my art assistant and we planned just minor stuff—I run a business, so, you know, I’m going down to meet with my accountant when I hang up with you. I run a business: I think up fucked-up shit in the morning and sell it in the afternoon. It’s a gay version of my father, who sold fire protection equipment.

John Waters’s work will appear in the upcoming group exhibition Queer Fantasy at OHWOW Gallery (July 11 through August 15). Beverly Hills John is opening at Sprüth Margers in London on July 1 and will be on view until August 15.

To contact Guernica or Meakin Armstrong, please write here.