Cindy Sherman, Untitled, 1979, International Center of Photography, Gift of Photographers + Friends United Against AIDS, 1998. © Cindy Sherman, courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures.

There’s a clock in the front windows of 250 Bowery, where the International Center of Photography (ICP) has recently relocated its exhibition space after a twenty-year run in Midtown Manhattan. “I wanted a space that felt very much of the commons, like a village square,” says curator-in-residence Charlotte Cotton, who organized the museum’s inaugural exhibit, Public, Private, Secret. Though a clock is a familiar form of civic architecture, this one, designed by software designer David Reinfort, uses CCTV cameras to serve as a real-time surveillance mechanism, translating images from the downtown street and the exhibition into a data-capture of human activity.

Even as the clock in the room evokes the panopticon of contemporary urban surveillance—the all-seeing eye of security monitors, webcams, iPhones—Cotton does not aim to provoke paranoia. “We wanted to create something that we call beautiful awareness. We wanted you to think about how you, in a space, actually create this data that is readable by humans as well as by machines. That’s the climate and context that we’re in.” The concept brings to mind Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida, in which he writes: “I love bells, clocks, watches—and I recall that at first photographic implements were related to techniques of cabinetmaking and the machinery of precision: cameras, in short, were clocks for seeing.”

Cotton’s ability to seize the essential and enduring from the stream of cultural change defines her work. A British transplant, she began her curatorial career two decades ago at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Since leaving, she’s pursued independent curatorial projects, including stints at LACMA and New York’s Katonah Museum of Art, and has authored the books The Photograph as Contemporary Art and Photography Is Magic.

She arrives at the ICP at a moment of transition, as the center works to redefine its role in the field of visual culture within the cramped constraints of New York real estate. Public, Private, Secret, opening later this month, explores image-making in a post-Internet age and calls attention to the role of the digital commons in shaping individual identity. In the first gallery, four videos play on the walls of the darkened room and panels of mirrors create both spatial uncertainty and a heightened state of self-awareness. The flash of a cell phone camera bounces off the mirrors, which transform the space into a staging ground for self-presentation. “Actually,” Cotton says, “we’re just acknowledging that every time you enter a space, you are on public display. Nothing is private.”

The second gallery combines historical precedents, new video work, and curated real-time media streams, “which are difficult to describe,” according to Cotton, “because it’s literally the first time you’ve seen it played out within an exhibition.” These real-time curations reflect how we’re representing and reinventing ourselves using the social-media machine. A celebrity leader board, an exploration of Instagram “hotness,” images of gender crossings, weight loss, plastic surgery, as well as spiritual conversion signal the freedom and plurality made possible by the Web.

If this sounds like a funhouse for narcissists, Cotton highlights what interests her most: the agency of self-representation, which, like fluency with language, offers a form of power. This idea is rooted in earlier forms of photography: on a wall across from Rashid Johnson’s Self-Portrait with my hair parted like Frederick Douglass (an homage to the most photographed American of the nineteenth century) there are three of Sojourner Truth’s cartes de visite, which the former slave inscribed and sold for twenty-five cents apiece: “I sell the shadow to support the substance.”

They knew even then, says Cotton, that the image is a cipher as well as a projection. “The real beauty of the time we’re living through is that we can deploy our self-image in ways that can have radical social implications.”

—Nicole Miller for Guernica

Guernica: Gabriel García Márquez has said, “All human beings have three lives: public, private, and secret.” In the digital world, these lives often converge. How do you understand their relationship?

Charlotte Cotton: How you make those distinctions is highly subjective and personal. I’m not going to overdetermine the relationship between those three elements, because I think the whole point is that there aren’t clear demarcations. More platform-sensitive generations will make distinctions between online and in-person intimacy, whereas fourteen-year-olds have very nuanced online selves and might embody their virtual identity in the physical, analogue version of themselves. They have a much more pluralistic understanding of the self. I don’t think we’d be here now in this amazing sexual and gender revolution without the online space where young people can see and share other versions of identity and sexuality.

What I like about the title of the show [Public, Private, Secret] is that, although it suggests the anxiety and danger of not having boundaries between these aspects of ourselves and being caught in these larger mechanisms, it also suggests that there’s something quite magical that can happen when a secret is no longer a secret—or is a shared secret or a common secret. By allowing those boundaries to be porous, certain forms of oppression may be lifted.

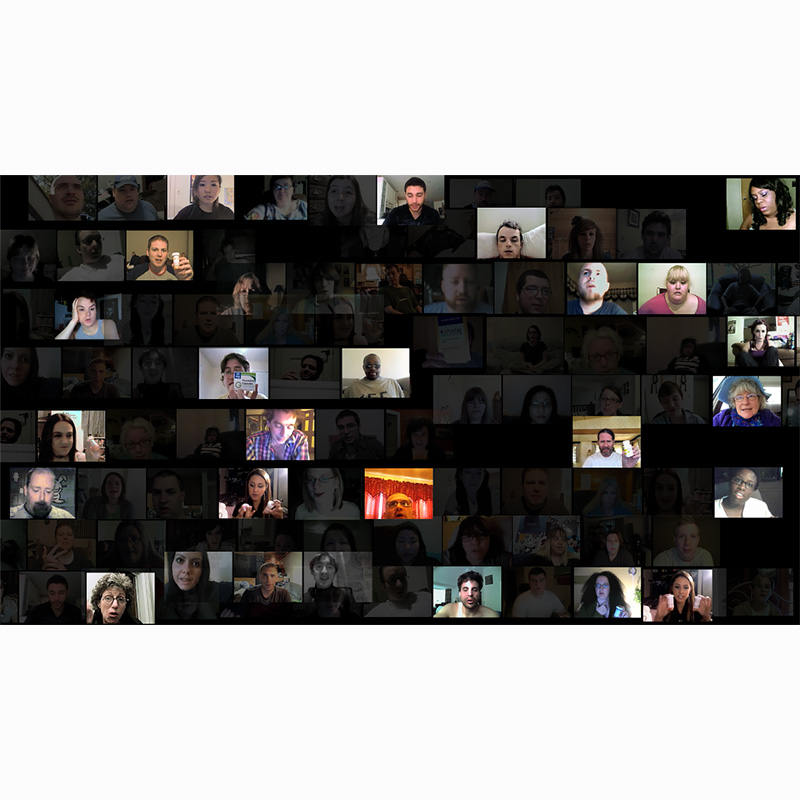

Guernica: That’s happening in the videos you’ve chosen for the exhibition from Natalie Bookchin’s Testament series. She takes material from vlogs and synthesizes individual stories into an almost symphonic chorus. In the videos presented here, individuals struggle to articulate their sense of isolation or their sense of deviance from some social norm. But as the artist compiles their stories, the narratives begin to repeat and become familiar, which suggests that they share a common experience and connection made possible by the Web. On the other hand, in this context, the most personal or confessional form of expression begins to sound borrowed.

Charlotte Cotton: Yes. I felt it most in her video “Laid Off,” where people describe their experience of being fired. You feel that these people aren’t getting angry enough, or they’ve internalized a script that says, “I’m going to work my way out of this. I’m going to be a winner.” They’re not spiraling into the place where I would probably go, where work is tyranny and the whole system is messed up. So even in a piece that is amazingly empathetic to human beings, you can see the failure of these very controlled formats of expression—even if it’s just control by length of time or by the availability of language or by their context outside an explicitly political group such as a labor union. The limitation of the vlog format is that it may seem to give people enough, when they actually have no real autonomy.

Guernica: The selfie is the other form of self-presentation that comes to mind, as a format that’s both personal and standardized. How do you understand the selfie in the context of other historical forms of portraiture?

Charlotte Cotton: I have to admit to you, I am the person who’s done probably the least analysis on the selfie, because it’s a bit like pornography for me. It’s this masturbatory, repetitive act that I’d rather wasn’t part of my routine. What were you thinking of—do you see a connection between the selfie and historical portraiture?

Guernica: I was thinking of portraiture during, say, the Renaissance or the Victorian era: oil paintings that are highly stylized versions of the individual, using standard conventions in order to communicate status and class—in the same way that the selfie registers social or sexual capital among young people today.

Charlotte Cotton: Yes. That’s a really interesting point—and it’s important to ask: What are the desirable attributes now?

None of us knows the implications of spending this much time crafting your own image.

Guernica: In her new book, American Girls, Nancy Jo Sales interviews thirteen-year-old girls who are very active on Instagram and Facebook—they might take seventy selfies for every image they post, and they’re actively monitoring the comments. It’s like a full-time job, fraught with anxiety and adrenaline. They seem very aware that their image is an emblem of status and desirability and their value in the social and sexual marketplace.

Charlotte Cotton: It’s a form of social modeling that young people are doing. Last year, Rizzoli published Kim Kardashian’s book Selfish, which is a really well-sequenced series of selfies that takes you through the lexicon. It’s like the Bible of how you do this. Young girls are modeling themselves on her image and its commodification. They understand that your image is your currency in this world.

There’s the other side of it, too, which is just how specific and nuanced relationship-building is for young people using social media. It’s no less sophisticated or tightly controlled than the playground, in terms of how you become friends with people, how you work out whether somebody is legit. So I’m not concerned that these kids don’t know what they’re doing, because with every generation, whether it’s rock music, drugs, or selfies, there will always be something that we think young people can’t handle. None of us knows the implications of spending this much time crafting your own image.

Guernica: I’m also interested in how cities, governments, or corporate institutions represent the human face—for forensic purposes, for example, or for market research.

Charlotte Cotton: The reading is very different. Just as the clock oscillates between human reading and machine reading of the body as metadata, the show tries to introduce ideas like biometrics and facial recognition software—without fetishizing these things. I didn’t want to do a scary thing like, Did you know you have been filmed 300 times today in New York City? Zach Blas’s Facial Weaponization Suite explores what you as an individual can creatively do to navigate the surveillance state. His radical strategy of wearing masks and his video is amazingly informative and tells you exactly what facial recognition is used for.

I love the idea of an artist using that technology in a deeply subversive way and as a mirror. In their new book, Spirit Is a Bone, Oliver Chanarin and Adam Broomberg use photo recognition software developed by the Russian government to identify people in crowds. You can take a very partial image from CCTV crowd footage and reconstruct a 360-degree portrait of this person. We’re showing a portrait called “The Revolutionary,” which borrows August Sander’s approach to citizens in Weimar Germany and uses this Russian modeling software to depict a member of the Pussy Riot movement.

For me, it’s not so much that we want to raise these fears and then move on to the next anxiety. I’d rather navigate these questions with an artist, because personally—and this is a radical proposition—I don’t think there is an expert voice for any of this. I’ve almost given up expecting that there is such a thing as an expert.

That image is the point at which they stop being schoolgirls and become terrorists.

Guernica: When the government is looking for a criminal in the crowd, it construes people in terms of culpability: innocence or guilt. When a corporation uses emotion recognition software to gauge your reaction to a carton of milk, it construes your body as a consumer. So there are these different modes of seeing what it is to be human, which have important implications for social classification, stereotyping, and racial profiling.

Charlotte Cotton: Absolutely. Think of that picture of the Bethnal Green Girls going through airport security on their way to Syria. That image is the point at which they stop being schoolgirls and become terrorists. That’s the state’s reading of who these young women are. It’s just a statement of fact: our bodies are used as metadata for these different systems. An artist can bring you into direct relation with that fact and its implications.

Guernica: It seems to me that Jill Magid’s work in this show, Evidence Locker, is trying to reinscribe the human form on the techno-bureaucratic landscape. She collaborates with the Liverpool police to document her movements using citywide video surveillance. Do you have thoughts about the kind of evidence that she creates?

Charlotte Cotton: Her project wouldn’t work if it weren’t her own body—and it wouldn’t be so striking if she weren’t a woman. There’s a certain risk that she takes as a female, putting herself in complicated, ambiguous situations and submitting herself to a paternalistic gaze. At one point, in her video Trust, she’s being guided by a policeman who’s watching her on CCTV, so there’s this very humdrum voiceover: “Alright, Jill! If you just take five steps to the left and turn to the right, you can sit down there.” She’s wearing a red coat, almost like Little Red Riding Hood. It’s not a macho position but she’s placing her body in a situation where things could go wrong, and there’s something important that happens when you’re willing to make use of your own body.

In the show, Magid’s work faces images from Sophie Calle’s The Sleepers. Calle’s work also involves a kind of physical bravery. She puts herself in situations where the power dynamic is not clear at all, and it’s through the engagement that we can arrive at some clarification of what’s actually going on psychically. Like Calle, Magid maps her journey through the city and documents or provides evidence of her actions—her own being.

Guernica: There’s a well-documented link between the rise of cities and the development of photographic technology—street photography, for example, is aligned with the nineteenth-century tradition of the flâneur. I wonder how photographic images shape our experience of cities today—and vice versa. What role does the camera play on the urban landscape now?

Charlotte Cotton: We tried various ways of integrating what you might call street photography into the show. We looked at street portraits taken during the Second World War, and we saw so many isolated figures in the streets—solitary silhouettes in mid-century, war-torn Europe. I was also reading about Vishniac’s street portraits of the Jewish diaspora—held in ICP’s collections—during and between the wars. Often, you’d get this silhouetted figure slumped against a wall or walking down a cobbled street. There’s the language of black-and-white and these isolated figures ostracized from normalcy. I think the history of street photography—particularly during that time, when people were dislocated and isolated and on the move, does actually tell us a lot about all of the things that we’re interested in now, either because of the Web or because of contemporary traumas and disasters. They were happening throughout the twentieth century, and they were represented in a certain way. I think that the role of curating an exhibition is to reanimate history and make it relevant to a contemporary viewer.

Guernica: Perhaps the street photographer has been replaced by the security camera.

Charlotte Cotton: Andrew Hammerand created a piece called The New Town, where he hacked into a CCTV camera in a planned community in the Midwest. He created stills that feel very ominous, like something’s happening there, but you don’t know what—this sort of suspense. And nothing bad, literally, ever happened in the town.

Guernica: I think surveillance images are so eerie and sinister in part because nothing is happening. You’re waiting for it.

Charlotte Cotton: Totally.

I decided that the joke could be on heterosexuality—something that’s already designated as normal—because it could take it.

Guernica: I wonder how the pervasiveness of public space affects our experience of intimacy—particularly our own sexuality.

Charlotte Cotton: I decided that heterosexuality would be the foil for the part of the exhibition that engages with sexuality. I didn’t want to introduce a lexicon of deviancy—subgenres of sexuality and photography’s relation to them—or, indeed, to go the other way into a Pollyanna-ish embrace of all forms of sexuality as socially equal. So I decided that the joke could be on heterosexuality—something that’s already designated as normal—because it could take it.

We looked at things like the Kinsey archive, and what I found was that the pictures didn’t actually maintain the agency of the subject or indeed the maker. It just ends up being a woman in fetish boots. The visual experience, if it’s anything, is titillating, which is actually not the point of our attempts to think about sexuality and intimacy within the context of this exhibition. I wanted to activate photography and sexuality and voyeurism in a way that was so pronounced that you’re almost standing back from it. Larry Clark’s photo from Tulsa, for example, is really humdrum in one sense—it’s a family snap in a suburban living room—but they’re shooting up. Or Barbara DeGenevieve’s panhandler work, which is really complicating what it means to invite a homeless black man to come inside and negotiate a portrait with her. These pictures have the agency of the situation that they’re born out of.

Guernica: It sounds like you’ve gotten back to something very basic, which is the relationship between looking and desire. Which is really about the promise of revelation—the hope that the subject of your gaze will reveal something to you—whether or not that revelation is prurient. And that’s really what eroticism is—the anticipation of disclosure.

Charlotte Cotton: Right. Proper voyeurism. It’s not the actuality, because you’re distanced from it; there’s no bodily meeting.

Guernica: These images also reveal the other side of arousal, which is banality. In a lot of webcam images, you see something that one writer has described as “The American Room,” which is this kind of beige, suburban, nondescript space. The photographers you’re thinking about seem alert to the ordinary space in which the exotic is defined. I’m thinking of the work Jack Webb Suspects His Parents, where the artist asks ordinary couples to let him photograph them having sex; or Larry Sultan’s The Valley, where he photographs a porn set in the San Fernando Valley, and you see the dishes in the sink and the production assistant wearing cargo shorts.

Charlotte Cotton: Jack Webb’s images were pre-webcam. He’s photographing couples who have never done this sort of thing. They haven’t tidied up their homes, and the sex is naturalized in its ordinariness. And Larry Sultan’s work is all about looking at looking, within the context of pornography; the images are not sexually gratifying. These are dentists’ homes being rented out for three days, which is the mainstay of pornography—it’s set within a suburban context. Very pedestrian. This series of pictures uses heterosexuality as a way of moving up and down the Richter scale of normalcy, exploring how we might represent intimacy and our sexual connections with other human beings.

There’s only one point in the show where you’re asked to acknowledge your voyeurism, which is the stereoscopic nude, where you look through a pair of stereoscopic glasses positioned quite low on the wall. It’s there to remind you that photography’s relationship with pornography is as old as photography. That kind of unholy relationship is formed from the very beginning, and there’s a reason why: it’s thoroughly enjoyable to be that voyeuristic. Voyeurism is a very old modality, and most of the history of photography is in some way related voyeurism. I think the twenty-first-century modality is exhibitionism. Exhibitionism is our contemporary strategy for maintaining our boundaries, which is to be boundary-less—to put everything out there before somebody comes and violates or penetrates something that we’re keeping sacred.

Guernica: In your essay “Nine Years, A Million Conceptual Miles,” you write: “We are not only a civilization of amateur photographers; we are amateur curators, editors, and publishers.” If we’re all “curators,” how does that impact your professional role?

Charlotte Cotton: In the context that I wrote the above quote, I was pointing to a number of things—the opening up of the range of skills and modalities in light of digital platforms, and the capacity for many without professional training to reach an “audience,” as well as the general shift in culture toward multi-role skill sets that are needed in a precarious work environment. I don’t really have any major anxieties about the prospect of curating becoming a mainstream—even an oversaturated—notion. I take very little pleasure in the idea of rarefied circles.

I moved away from aligning myself so tightly to one institution and have gravitated toward institutions that are actively seeking change and where there is some pace to the impact I can make. I could not have undertaken this without a serious grounding in the old-school training as a museum curator. But since the early 2010s, I’ve wanted to define my curatorial work as a “practice” and as “my work.” I make distinctions between my labor, where I’m paid to professionally use my demonstrable skills, and my work, which belongs to me. The work includes projects like my book Photography is Magic, for instance, which was made without any institutional support. In this period of time, I’ve come to think of curating—to quote one of my closest collaborators [Mark Allen of Machine Project in LA]—as “doing creative things for other people.” Now that really interests and inspires me and actually goes to the heart of the journey I started when curators [in the UK] were literally public servants, i.e. a wing of the Civil Service!

Guernica: You mentioned your decision to de-couple yourself from a single institution—which reflects a shift in the way that museums have historically operated. There was a time when a curator might be associated with a single institution over the course of her career.

Charlotte Cotton: Yes, and there was a time when people had life-long jobs! And pensions! I think the de-coupling is an oscillation between institutions needing to bring in or keep very change-driven people in an organization and giving them some authority to bring about change, and institutions not being ready to unpack their basic hierarchical structures in order to embed such practices in the day-to-day running of their institution. That’s one way to look at it. Another way is that the at-large roles and emphasis on consultation reflect the precariousness of work in general for non-executive roles. I also think it’s the influence of the creative industries where “creatives” move around a lot.

For me, I had a turning point in life that was undoubtedly militated by the financial crash and its aftermath, plus a really difficult work situation, and my concern that if, as is likely if I am lucky, I am barely half way through my working life, it wasn’t time to start compromising. I didn’t want to look back and think that what I achieved was a graceful and patient navigation of the political blows of one institution. Rather, I wanted to be more optimistic and challenged and to think of this as a period of life where I had some amazing adventures, met great people, and made some good things in situations that I would not have found if I had stayed in one place.

Guernica: How do you understand this moment of transition at ICP, as it moves from its Midtown home to this new space at 250 Bowery—and as you’re trying some very innovative programming?

Charlotte Cotton: As you know, most museums are quite guarded in their approach to risk. There’s a worry that people are going to miss the old ICP, but I don’t think anyone misses the past that actively or for very long. It’s more a question of curating a space where there’s an important, relevant journey to go on. Over the course of this show, we’ll be commissioning essays that come at the idea of privacy in different ways. We’ll have workshops—including, “How to Be Anonymous”—as well as lectures and discussions. We’ve tried to create programs that are generative rather than statements with a full stop. But the show can’t just be the boring bit. The show has to feel like it’s on that journey too, which requires doing things a little bit differently. It’s not a museum show where you look at the work, read the text, and move to the next picture. It’s a constellation of material, and the show is not scared of being quite dramatic. Increasingly, we talk about the exhibition as a physical experience. In an era where digital or virtual is the default, the actual coming together into a physical space has to be an experience that you don’t want to miss.

Ultimately, the reason why this can happen at ICP is embedded in its DNA. The ICP started as an idea and a fund, the International Fund for Concerned Photography, which gained a physical building in the early 1970s. At that point, across the Western world, people began to think about photography as a cultural subject. Until that time, nobody had defined it and there wasn’t a critical mass of experts, so people came with enthusiasm and different skills sets—writers, practitioners, art historians, and makers—to define this subject called photography. The other museums in the city that engage with photography essentially narrate the medium within the story of modern and contemporary art. The ICP is the only institution in New York that asks: What are the social implications of our visual world? With that as our starting point, I thought, well, let’s not be coy about it. Let’s really try to explore these social issues.

To contact Guernica or Nicole Miller, please write here.