When we talk about class in America, very rarely does the subject of art arise. Even less the role of commercial artists, who employ beautiful visuals and the currency of style to sell products and companies. These individuals register the influences of the media and advertising power structures on society, but how they use them is a matter of personal values. For Milton Glaser, 84, the most impactful graphic designer of our time, the business of identity—also known as branding—has deep moral implications. Responsibility and meaning are directly connected to his process. The intended effect of design on the consumer is action: when he can, Glaser infuses his work with art, proving, over a five-decade career, that it is the common thread that bridges class divides and other differences. “Art really has a healing role in the world,” he explains. “It makes people conscious of their commonalities.”

Glaser’s most iconic image is part of our daily lives: his I (heart) New York logo, ubiquitous on the home turf and appropriated worldwide in various incarnations, was a commission by the New York State Department of Commerce in 1977, when the city was overrun by violence. Glaser’s design lifted spirits, reminding everyone of the unique spark that holds together the world’s cultural metropolis. Hardship in New York was always an issue, but, as he points out in the interview that follows, “Now, there are more poor people. There’s less available housing. If you are a normal person, you can’t live in Manhattan. In a very short time, you won’t be able to live in Brooklyn, either, unless there are six of you.” Inevitably, this dynamic trickles through to the creative communities. Art graduates have no support, and mostly wind up teaching to make ends meet. Achieving fame is extremely rare, though “everybody wants to be Warhol, or Jeff Koons,” Glaser says. For his part, “I just wanted to do work. I wanted to have a job. I wanted to earn a living.”

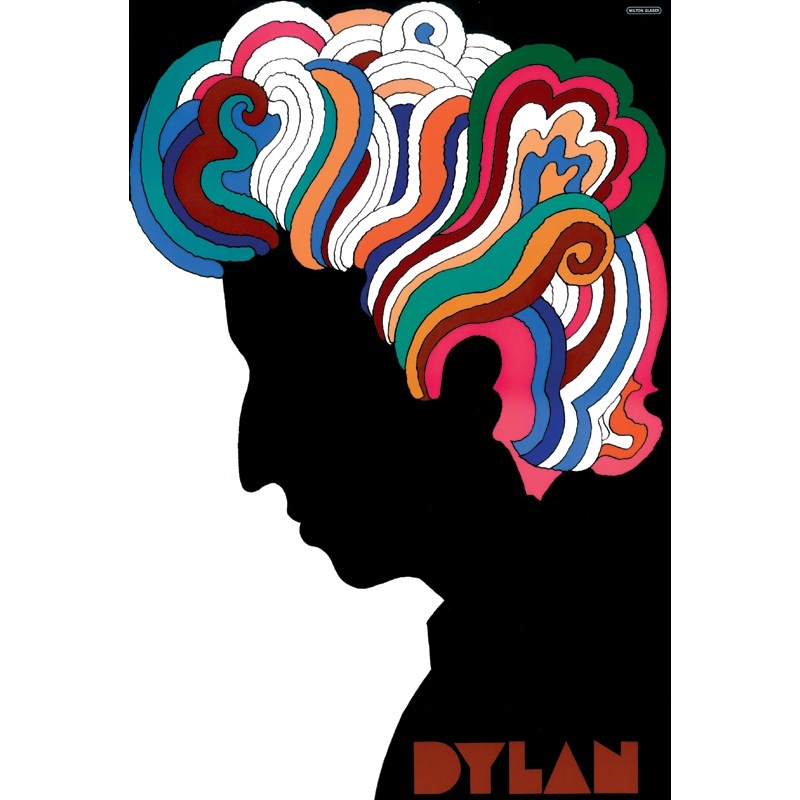

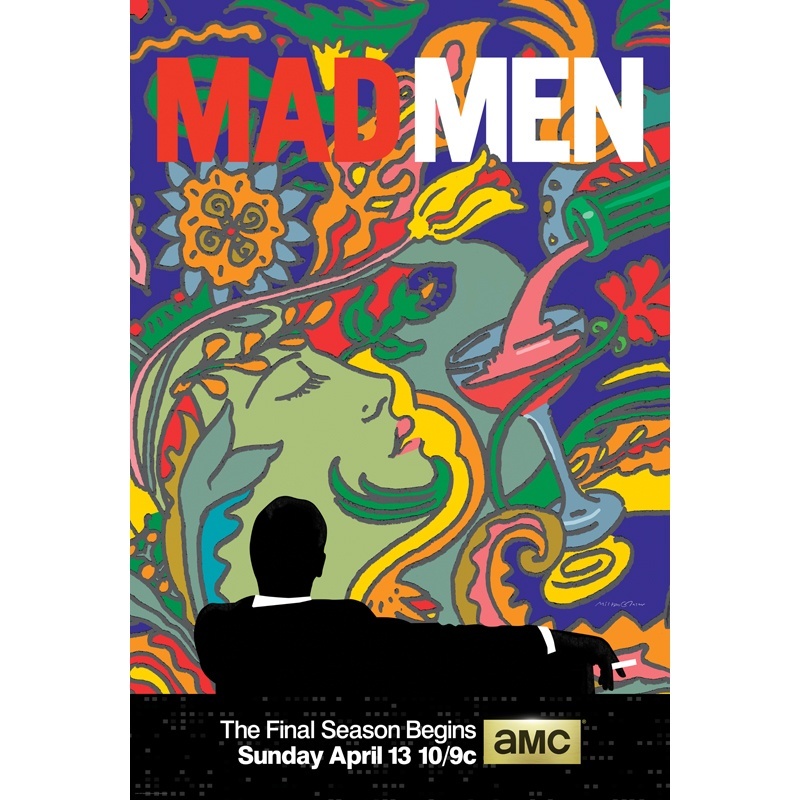

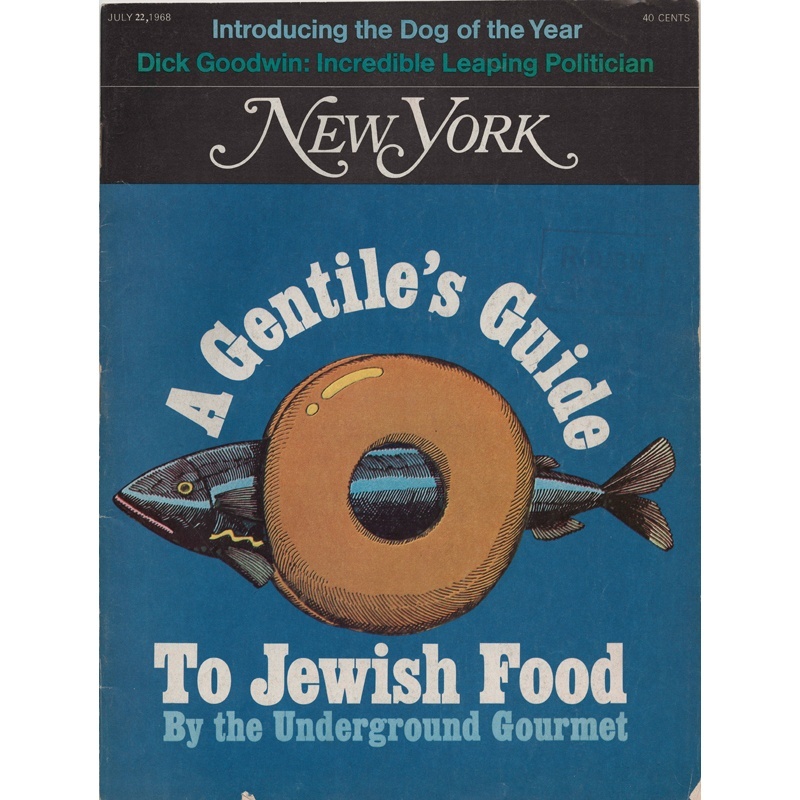

Branding is only one part of his output. As early as twelve years old, the Bronx-born Glaser was working with lettering, layouts, and illustration. After graduating from Cooper Union, he had a two-year apprenticeship in Italy with the painter Giorgio Morandi. He returned to open Push Pin studios. He has since worked on newspapers, magazines (he founded New York in 1968 with Clay Felker), illustrations, record albums, book covers, posters (Bob Dylan with psychedelic hair), global identity (United Nations, Brooklyn Brewery), architecture, and interior design. He has had one-man shows at MoMA, and the Pompidou in Paris. In 2009, President Barack Obama awarded him the National Medal of Arts; he is the chairman of the board at the School of Visual Arts. Recent work includes the promotional materials for Mad Men’s final season.

His new personal passion project is the upcoming “It’s Not Warming, It’s Dying,” a social awareness campaign about climate change, encapsulated in a lush green button that deepens to an ominous black, indicating that the wearer is acknowledging a global problem. “What the Right, the oil companies, and existing power structures have been able to do is constantly raise questions about whether [climate change] is real or not,” he explains. “They create enough noise so the people don’t know what to do. The National Rifle Association—which has an incredible amount of power with no real authority—has convinced politicians that if they don’t vote for their agenda, they won’t get reelected. This is along those lines: if enough people are visible across the world wearing this button, the indication of concern will be enough to change the activities.” Education, wealth, and rank mean nothing in this context: just the choice to acknowledge a human issue.

I met Glaser at his offices, a 32nd Street townhouse he has owned since 1974, with the words “Art is Work” emblazoned on the front. Over six feet tall, he is at once stern, funny, sarcastic, and thoughtful.

—Alex Zafiris for Guernica

Guernica: You take pleasure in choosing projects responsibly. Now that culture is increasingly homogenized and monetized, and the individual has a more self-interested agenda, how do you hone your instinct? Is it harder now to find the common thread?

Milton Glaser: There is such a thing as art, and there’s such a thing as money, as culture, as ethics. They all have some relationship to one another, though sometimes, the affinities are not very clear. Art really has a healing role in the world, and it makes people conscious of their commonalities. That’s what it does more importantly than anything else. We invent it to prevent people from killing one another, by creating a common affinity, a connecting tissue between people where none seems to exist. That doesn’t seem to be exactly the role of money, or commerce, or materialistic objects, which have their own independent life and force. Historically, most obviously in religious terms, art has been used in some way to mitigate or modify this endless desire for acquisition, and for power. So you might say that art, in one form at least, is a means of controlling the need for power, control, and superiority over others. How you then unify this into a theory is another issue.

Guernica: You have mentioned before that “branding” is a hideous development, in terms of how to conceive of and visualize status.

Milton Glaser: Yes, I hate the word “branding,” particularly because it has replaced the activity of design to a parochial and narrow issue. Design has a large compass, and branding has a very limited one. But it is where the money is for people engaged in the practice. Corporations are very interested in having identities that can be used to make more money. Essentially, the reason you brand anything in commercial life is for recognition of entities that want to use that recognition to sell something. Everyone has the option of what companies and what institutions they want to work for. The question of doing no harm becomes an issue at that point. There’s nothing wrong with branding itself. The issue is: for what reason, and who benefits?

Guernica: From a visual point of view, how does negative or manipulative branding—in respect to, say, class structures—manifest itself? Are there any stories or habits that reoccur?

Milton Glaser: First of all, it is historical. The church branded itself a long time ago, and other institutions have used branding or insignias or motifs which are susceptible to the worldview of any particular world culture at the time. Certain things work at certain times. In a capitalist culture in general is the need for endless buying, the repetition of the buying pattern: if you buy a shirt and pants, you don’t expect to keep them for forty years. What you will do is you’ll keep them long enough so that it doesn’t look out of style. What does style mean here? It means a group of signals that determines whether you’re inside a certain community or outside that community. The genius of capitalism is to convince you to be adaptive to the change of fashion. There’s benefit in looking like others of your kind. It’s a complex issue. The phrase “built-in obsolescence” applies here: the invention of the need to create such a thing as a stylish idiom, so that it can be dispensed with after a five- or ten-year cycle. This is a product of a materialist culture, of capitalism, where you have to keep people buying all the time.

Art and design are like love and sex. They’re fine independently, and you can use them without one engaging the other.

Guernica: Can anything be timeless?

Milton Glaser: “Timeless” is a funny idea. In some areas, say, fashion, the cycle is three, four, five years. In design, it might be a thirty-year cycle. Every genre has its own cycle, and you have to understand what to exploit if you’re selling things: to exploit that cycle, or withdraw from it. One or the other. When you say timeless, some things seem to persist in people’s minds for a very long time, and don’t seem out of style. Coca Cola, for instance, is a brand that has a very durable history. Most recently, graphically, they changed their mode of communication by changing their bottles. The iconic part has been cleaned up, but very much resembles the original, done for a very different moment in time. People who specialize in this make modest adaptations of the form, so that they can stay within the genre. As a designer, that is what you are asked to do more often than anything else: make small modifications so that they don’t look out of time, out of class, or out of category. Making it look appropriate for the occasion would be a way of describing it.

Guernica: What about graphic design education? A lot of graphic designers coming up don’t even remotely consider what they do as art.

Milton Glaser: As art? Well, it’s not. Art and design are not the same thing. They’re two different activities. I’ve been putting it this way over the last six months: art and design are like love and sex. They’re fine independently, and you can use them without one engaging the other. Every once in a while, you find you get both from the same source, but that’s unusual. Design does not have art as its objective. It has a goal, and it means moving from an existing condition to a preferred one. Art is about the transformation of human experience, establishing the common ground between people. Those are two very different functions. So, sometimes you do work with design that also is a work of art. You can tell it only experientially, and not by somebody else’s description. They can call it art, just as anyone can claim to be an artist. There’s no test. But that has nothing to do with the issue. The issue is whether the work you produced is experienced by others as being transforming.

Guernica: Your work always walks that line.

Milton Glaser: My aspiration is, when the opportunity exists, to attempt to bring art into the realm of design. But they are not necessarily congruent. Sometimes there’s a very low art content, but it is effective anyhow. You can look at something and say, “It’s ugly, but it works.” Sometimes, it’s very beautiful in the sense that art and beauty are linked, and it changes your perception of reality. And even there, you can say, “Well, it doesn’t work very well, but it really is beautiful.” And there, you immediately see the distinction between two disparate functions, right? Trying very hard to smash them together. Very often not succeeding.

Guernica: Do you try to teach this to your students?

Milton Glaser: For those who want to hear it, and for those for whom it’s an issue. For many people, being a designer is about solving problems and making a living. For other people, it may have another kind of social or metaphysical purpose. That’s a very personal decision everybody has to make, and it’s not only in the realm of art.

People ask me for sort of the rules of graphic design. I always say, “First, do no harm.”

Guernica: Do you find that there is an increased or decreased interest in this?

Milton Glaser: I have no idea. There’s a lot of talk about social intention in the communication field now, but whether that talk is ever translated into a real commitment remains questionable. It is very hard to measure. It is certainly of interest to me, and my background and history have been linked to political action and the idea of social good. People ask me for sort of the rules of graphic design. I always say, “First, do no harm.” I am committed to that idea. The other part is that there’s an essential contradiction between the two. In the realm of persuasion and advertising, the intent is: to make, or push, people toward activity that is not necessarily in their own good. It may not be necessary to buy a new jacket after a year, but advertising wants you to believe that it is a good thing to do. This is a benign example, because there are much more dramatic examples. The question is whether you want to urge people to buy a jacket, but that becomes a different scale of value. It’s different to urge people to buy another piece of clothing than it is to urge them to drink something with a lot of sugar in it which is poisonous. So even though both of those things are persuasive, one does more harm than the other.

All of us have an index of how far we’re going to go to modify our own beliefs, and that is the human condition. We all are faced with: “I want to do good, but I really have to put bread on the table, I have to send my kid to school, so I’m going to take this job even though I don’t like the consequences of it,” etc. etc. But I don’t know of any life that doesn’t have that issue. The problem with the world is the nature of ideology itself—that when you believe anything, you’ve essentially closed your mind. Belief is a closing of the mind. That is a terrible limitation of the species, and very characteristic of all the people who are the most passionate about it. If you believed in communism, you discovered at a certain point that it turned and became oppressive. If you believed in fascism, as many people did, it suddenly started killing people. Any belief that represents your inability to examine new things without preconceptions is dangerous. And yet, people believe everything. Everybody you know believes something.

Guernica: Mad Men. That must have been fun.

Milton Glaser: It was a nice job. I wasn’t sure I could still do that kind of work. It was a kind of psychedelic drawing that I haven’t done for maybe twenty years. My work has gone in another direction. More conceptual, less illustrative, more symbolic. It was fine, it went easily and without any problems.

Guernica: Do you watch the show? I hear that the feelings, tones, colors, moods, and story lines are extremely representative of that time.

Milton Glaser: Well, if one can remember that time. I read recently that memory is just a device to justify what you’re doing today—that there is no such existing condition that is truthful.

Guernica: I feel that using old-fashioned story lines to shed light on present-day issues is a device that would suit you well. Was that your motive behind the drawings?

Milton Glaser: It was to evoke a particular spirit. It had the same relationship to a narrative about that period that’s done today, to a drawing of that period that’s done today, which is to say: it’s not exactly the same as the Dylan poster which it was based on, but there are enough references so you get the connection. What you want to do is not something that looks the same but is sufficiently distorted for this moment in time, so you think it looks like what it was.

If you are a normal person, you can’t live in Manhattan, that’s true. In a very short time, you won’t be able to live in Brooklyn, either, unless there are six of you.

Guernica: When you opened Push Pin, was New York much different?

Milton Glaser: A little bit. Certainly less affluent. In some ways worse, in some ways better. In 1977, when I did the I (heart) NY campaign, my wife and I were living on 67th Street, near the park, a very nice part of town. I remember we would talk about whether it was safe to go outside. There were so many muggings and attacks on the street, you worried about whether you could go out at night. From that point of view, things have changed a lot. And you can say, well, now there are more poor people—that’s true, there’s less available housing, that’s true. If you are a normal person, you can’t live in Manhattan, that’s true. In a very short time, you won’t be able to live in Brooklyn, either, unless there are six of you.

Guernica: Do you think this hurts the arts community?

Milton Glaser: It’s very hard to really make art, because there’s no support for people making it. There’s no support for the painting community compared to the number of students that pour out of all the schools in the United States. What have they got, 2 percent employment, and 2 percent, 5 percent, can make a living? They end up teaching art, because there’s no other way they can survive. There isn’t an intrinsic structure. There’s a lot of talk about providing even a bare-boned living for people who want to go into the arts, although none exists. I don’t know what painters do now, outside of the occasional show and teach. Unless you hit the jackpot, which is the other part of this extraordinary, entrepreneurial atmosphere. If you make it big, now you’re talking. Everybody wants to be Warhol, or Jeff Koons. So many are willing to gamble on the possibility. The odds aren’t very good. But that’s not why you paint, anyhow.

Guernica: No. Well—for some people, it is.

Milton Glaser: There’s a difference between people who paint for fame and money, and pursue it, and people who paint because they don’t feel they have a choice about whether to do it or not, it’s the only thing that makes them feel alive.

Guernica: And where do you stand in that?

Milton Glaser: I just wanted to do work. I wanted to have a job. I wanted to earn a living. I wanted to be as well trained as anybody had ever been. I wanted to know everything about the history of art, and what everybody had done in the past, and I wanted to develop skill of the most profound kind. I wanted to know everything about color, form, and drawing.

It still is the best thing I do. It’s the thing I look forward to doing. I would sooner go to work than go to any movie, or theater, or concert, or anything else.

Guernica: When did you decide to become a designer?

Milton Glaser: I went to the High School of Music and Art, which was a fantastic school. I went to the Art Students League while I was there—I started taking classes when I was twelve years old. I had a vague idea there were things I could do professionally, like lettering, and layouts, illustration, and so on. One thing led to another. I was extremely well prepared. I was very skillful. I also was willing to work my brains out. The idea of working sixteen hours a day was perfectly acceptable to me, because it was the thing that made me feel best. Work still is. It still is the best thing I do. It’s the thing I look forward to doing. I would sooner go to work than go to any movie, or theater, or concert, or anything else.

Guernica: You are heavily involved with those communities.

Milton Glaser: Sure. The act of work, instead of isolating me, actually integrates me into life. The work is not for me. It is because I’m part of a larger system. And the work is communal, in the sense that it has an effect on others. It is one of the reasons I never became a painter—it was just too hermetic, and too dependent on whether you managed to get into the system.

Guernica: Now that you are at the level that you are, do you feel that you have more freedom with what you want to do? Do you still enjoy the commission aspect?

Milton Glaser: I love commissions. But I only love them when I like the people who give them to me. All of this is really personal as much as it is professional. And I’ve always been very lucky: I’ve always had people in my life whom I had a personal affection and affinity for to work with. The guy whom I do all the Brooklyn Brewery packaging for, Steve Hindy. Had lunch with him the day before yesterday. Someone I really like. As a result of that, I want to do work that is in our mutual interest. We’re in the same boat, kind of thing, and that is the best context to work in.

Guernica: How do you find these people? Do they find you?

Milton Glaser: You hope they come to you. You stumble into them. And sometimes you find them, you lose them. Anybody who comes in through the door is potentially a good client or a bad client. You don’t discover that until you’ve worked with them for a while. Some last, and some disappear, and they just vanish very quickly.

Guernica: Back to “do no harm.” This is central to your practice. In your point of view, how does that relate to community?

Milton Glaser: It’s everybody’s personal decision. I don’t know what their relationship is to their community, and if they have a relationship with their community. The thing about capitalism and our financial structure now is that it tends to make that concern for community less desirable than the search for self-advantage. And the idea that it’s a competitive society linked to democracy. Suddenly we discover it’s not so democratic when you can’t vote and you can’t get out of your existing social condition: it acts in the opposite way, it’s one of the paradoxes of our social structure. At one point, the idea of individual performance and competitiveness and so on seemed very useful to us. Now that’s come around again, it’s not so useful, it’s become dangerous. Witness this by the small number of people who are vested in maintaining the existing condition. They have managed to keep everybody else, whose lives are at stake, at bay. You see that, inevitably, power corrupts. We are victims of the power in the world. So “do no harm” merely means: stop supporting the existing power structure, and live more socially, more communally, more concerned about everyone else. That old golden rule “do unto others” is still an operating system. But not very well observed in our time.

Guernica: And Cooper Union, now charging tuition.

Milton Glaser: It’s a very complex issue, very difficult. The problem seems to be that no one has figured out an alternative way to deal with the issue. There’s not a single person involved with Cooper Union, either the management, the alumni, or anybody else, that wants to charge tuition. But the change in the real-estate values in the city, and the economic structure of the school, has made it almost impossible to survive entirely as a free institution. It’s a great sadness, and they’re still trying to see if there are any alternative ways of dealing with it.

Guernica: Are you worried about how that will impact young designers?

Milton Glaser: Unfortunately, Cooper is a very small institution. The number of designers entering into the field is overwhelming. Everybody who doesn’t want to be a chef now wants to be a designer.