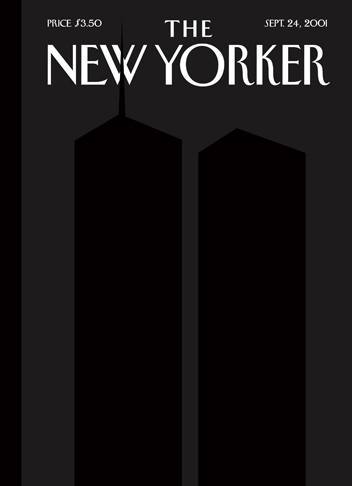

Françoise Mouly is one of the most influential editors in comics and illustration of the last thirty years. Since 1993, she has worked as the art editor of The New Yorker and has published such iconic magazine cover images as a black-on-black silhouette of the World Trade Center, a cheeky map of “New Yorkistan,” and Barack Obama wearing traditional Muslim garb in a conspiratorial fist bump with Michelle Obama. The hiring of Mouly ushered in a new era for The New Yorker. Unlike former editor William Shawn, who regarded the cover image as “a restful change from all the other covers,” she saw the space as a sort of mirror that had the potential to reflect and refract the cultural and political conversation.

Mouly, a Paris-born Beaux-Arts architecture student who arrived in New York in 1974, looked to comics to improve her English, and her interest in them deepened when she met her now-husband, the acclaimed cartoonist Art Spiegelman. “I totally fell head over heels with Art,” she says in the following interview, “with his aesthetic, with the medium, with all the possibilities.” Spiegelman, who in the ’70s had been creating independent comics like “Prisoner on a Hell Planet” and editing the comics magazine Arcade, acted as an evangelist for comics but failed to rouse the interest of mainstream publications. The combination of his inventiveness, humor, and vision, and Mouly’s production skills, architectural approach, and refined taste, came together in 1980, when they co-founded the annual comics magazine Raw.

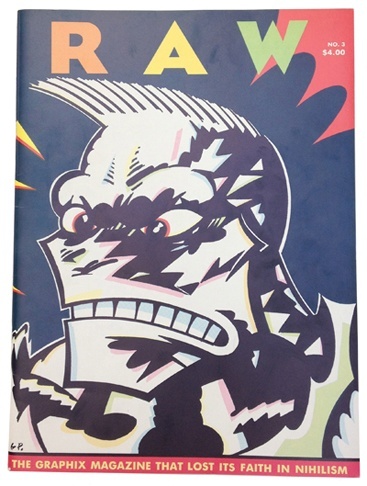

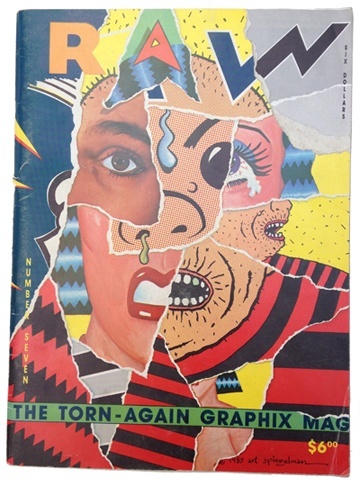

Mouly calls Raw a “manifesto,” a “catalog of possibilities” that elevated comics from the realm of sex and dope mags to literature and high art. As opposed to the predominant comics that existed at the time—gag comics, genre comics, subversive underground comics—Raw gave a large-format, full-color treatment to the work of carefully curated artists from around the globe. Contributors included Chris Ware, Joost Swarte, Sue Coe, and, of course, Spiegelman himself. At the time, he was working on his memoir, Maus, and included a chapter in each issue; his ensuing graphic memoir went on to win a Pulitzer Prize in 1992. Of editing and publishing Raw, Mouly says, “We had carte blanche because there was nothing else.” The magazine earned American comics the kind of legitimacy that the medium had in France and Japan. For her seminal contributions to the medium, critic and journalist Jeet Heer has called Mouly the Gordon Lish of comics.

When it comes to evaluating an artist, Mouly says, “I know what I respond to is a voice.” As she told VICE magazine, “From my vantage point, I try to be blind to the aesthetic visual quality. I try to not be seduced by ‘that is a beautiful drawing.’ The goal is to give a portrait of our times in visual snapshots.” She applied this ethos to Raw, which she and Spiegelman shuttered in 1991, and continues to take this approach in soliciting and publishing cover art for The New Yorker.

I met with Mouly at her Soho loft, and we sat in the spot where the multilith press machine that launched her publishing career originally stood. She talked extensively about the legacy and craft of comics, the political implications of art, and the democratic aspect of being an independent publisher. Mouly seemed to be in no hurry. “I’ve been a small publisher all of my life,” she told me. “I can do what I want when I want.”

—Grace Bello for Guernica

Guernica: I was wondering about your upbringing, and how that might have influenced your aesthetic.

Françoise Mouly: It’s a good question for me, because I can only find logic in where I am now by looking backwards. I could never have predicted, for instance, that I would be living in a different country and speaking a different language.

My dad was a doctor who was very disappointed that he only had girls. He consoled himself by picking one of his girls—which was me—and deciding that I was going to be his inheritor, that I was going to become a doctor. He was a surgeon. He was a pioneer in using plastic surgery in France. It started as reconstructive surgery after World War I. He operated on harelips, burns—it was really noble. And then the work that he did in the clinic seemed frivolous to me. Plastic surgery is such a displacement. If people feel good in their skin, then they’re beautiful, end of story.

Guernica: You wanted to find a path that was authentic to you.

Françoise Mouly: I wanted to find my own thing. My boyfriend was studying at the time at the Beaux-Arts to be an architect. That was so exciting. It was in the center of Paris. It was post May ’68. What we called la vieille école had sculpture studios and very old-fashioned busts that you would draw from, live models to draw from. I had no encouragement for any of the drawing or sculpting or anything [when I was growing up].

After two years at the Beaux-Arts, I became a little worried. At the time, there was almost no interesting work as an architect. In school, it was all about “design a city.” It was grandiose what the architecture students could do. But the reality was night and day.

I came to New York. I arrived on September 2, 1974. Early on, I stayed in various kinds of difficult [living] situations: the Salvation Army and YMCA and so on. So I started looking for a place for myself. I found this loft.

Guernica: This very loft?

Françoise Mouly: Yes. It was exhilarating. It was fantastic. It was all of the things that I hadn’t had in Paris: a way to earn money, the ability to have my own space, the autonomy, a sense of purpose. It was really exciting.

My English was still very poor because I mostly worked alone [at a newspaper stand]. I was looking at comics as a way to get into the culture and see a written language as it’s spoken. Somebody I knew also knew Art—he was living in California at the time—and gave me copies of the comics that he was making and publishing. I was really interested in his comics magazine [Arcade].

I was also given a copy of the strips that he made about his mother’s suicide, “Prisoner on a Hell Planet.” I was blown over by the work, by the intimacy of it, by how it got you into the mind of someone. How could someone dare be that intimate on paper? It was also structurally so interesting. It really was an interplay with the reader.

Press the image to enlarge.

Often, we separate intellectual discourse from emotional reaction. But I take such genuine pleasure in things that are intellectually well architected. It’s definitely an integrated experience for me. Much more than any kind of cheap, emotional pulls that you get in popular culture, when I read a sentence and it’s beautifully written, it can bring me to tears.

I know what I respond to is a voice. A voice is not just a stylistic thing, but it means someone who really has something to say. I think a lot of what I get from books—whether they be books of comics or books of literature—is a window into somebody’s mind and their way of thinking. I love it when it’s so specific. It’s a new way to look at the world. It’s as if I could get in and see it through their eyes. It also reaches a level of universality because, somehow, I can recognize some of my feelings in seeing somebody who is actually expressing their own inner reality. Even though Flaubert has not been in Madame Bovary’s skin, you do get a sense of what it’s like to be that person. It’s a kind of empathic response when you’re reading it.

From the minute I met Art, he was courting me by showing me the comics that he loved and reading me “Little Nemo” and showing me the work of George Herriman.

In New York, people were so responsive. Certainly, Art was. The fact that I knew nothing about comics was not just okay, but actually welcomed by him.

Guernica: Because other people had a preconceived notion of what comics were.

Françoise Mouly: Right. It was fascinating. I couldn’t believe I was getting this. Also, he was in the middle of putting together the more formal and experimental strips that he had been gathering since 1972. He was putting together a book, and he was doing an introduction for it, and he was doing color separation—he was doing all the production.

Guernica: Is that when you were learning how to do production, too?

Françoise Mouly: I did! That was the other thing. I loved doing production. It was the answer to all my dreams. It was making something happen that then would get built. It was as if I could design a city. It was manual labor, which I’ve always loved. I think my dad was right: I was good with my hands, and I would have been a good surgeon.

It was very similar to what I had done with models and drafting in school: the same drawing tables, T-squares, and triangles. We worked on vellum, and the cartoonists worked on Bristol. But that’s about it. All of the hand-lettering, stencils, the mechanical pencils—so many of the tools were similar.

I totally fell head over heels with Art, with his aesthetic, with the medium, with all the possibilities. I was there with him at the press, getting his book of comics printed. One of the forms was badly printed, and I saw the book being destroyed in front of my eyes. I felt a visceral pain.

Guernica: Was that Breakdowns?

Françoise Mouly: Yes. I really wanted to master [production]. I wanted to publish all the stuff that Art had shown me that was not available anywhere. I wanted to do books of “Little Nemo” and Töpffer and George Herriman and Caran d’Ache.

This was the beginning of instant printing. I had a printing press in my house. To be able to make a printed object was magical. That gave me the ability to print my own little booklet. At the time, nobody was publishing comics. Art’s magazine [Arcade] folded for lack of distribution. I thought that the best way to gather all these comics—I wanted to do a magazine.

We went to Europe and met all of the people who were doing interesting things with comics. We were able to pick from the French comics and the Belgian comics and the Spanish comics—we didn’t have to take all of the kids’ stuff. We were able to skim from every culture.

Guernica: And it was such a contrast to what was going on with comics in the US. There were a limited number of outlets: Mad magazine, Playboy, High Times.

Françoise Mouly: Mad magazine was a very, very pale leftover of what had been great when Art was a kid, but it was defunct in terms of being an interesting place.

Because of where I come from, I fell in love with what was made by hand. What I like in comics is that you can actually see the person doing it. So that moment with Art’s strip about his mother’s suicide, the immediacy of reading somebody’s diary…

[The imagery] doesn’t have to be that elaborate. Often, in comics, it gets very distilled. Art, for example, uses many different styles, but his voice is very consistent. He’s always concise and clever and funny. That’s true of somebody like Chris Ware, who has an emotional quality to his work—but it’s boiled down and it’s very sober and spare. Each [word] has great weight. It’s not just pictures, but it is graphic design in the sense that they are composed and architected in a specific way.

My training in architecture is really good and very useful for all of this. It was architects who invented the idea of form and function. The form should express the function. It has an honesty to it.

Guernica: That name, Raw, seems to capture all of this: the focus on the handmade, the authenticity, the ideas rather than the style.

Françoise Mouly: When I looked at the magazines that existed, such as Métal Hurlant, or even when I looked at underground comics, there was a kind of a house style. Métal Hurlant was all a certain kind of hyperrealistic, airbrushed look, which was the predominant style. The underground comics, in contrast, were always scritchy-scratchy and incredibly dense. [Robert] Crumb, for example, was looking at things like early “Popeye” and things that were very densely cross-hatched with lots of details. Even Will Elder in Mad.

Raw was a manifesto. We had carte blanche, because there was nothing else except underground comics. We were always figuring out, “Is this a unique voice? Is this different?”

Around the same time, Robert Crumb started Weirdo, and he picked up where Arcade left off. His editorial policy was the opposite of ours, which is that he didn’t want to leave anything out, and he wanted to be all-inclusive.

Guernica: And Crumb seemed to be interested in outsider art.

Françoise Mouly: He was interested in challenging and violating taboos, which a lot of underground comics were about—not being confined to a commercial purpose like selling newspapers or magazines. Having the freedom of an artist and not worrying about a publisher, who will say, “You can’t do this and you can’t do that.”

You mentioned Playboy—yes, Playboy was heavily edited, and it could only say certain things in a certain way. The New Yorker had no place for any of those [unconventional] artists. It was completely closed off to that kind of discourse. And some underground papers—there was a network of distribution, but by the late ’70s, it had died off.

So for Raw, it was clear that what we wanted was a catalog of possibilities. We launched it saying that it was going to be biennial—either twice a year or once every two years. We looked it up, and it can mean either.

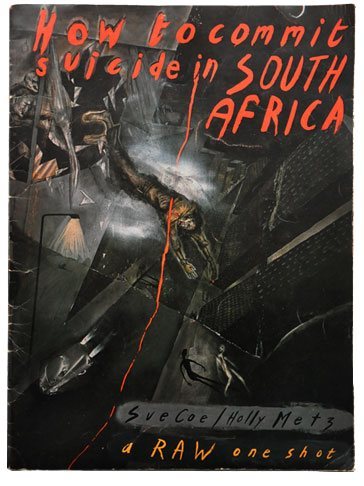

Guernica: I wanted to speak a little bit about the political aspect of the comics you’ve published. In Raw, there was a lot of room for you to experiment with, for instance, the provocative work of Sue Coe or to critique President Reagan.

Françoise Mouly: It’s useful to be born in a different culture because you see things that are not obvious. I come from France. In France, there isn’t a pretense of objectivity in publishing. I discovered—and I don’t agree with it—that in the US, the New York Times or The New Yorker has to pretend to be objective, and if they present this point of view then they have to also present the other side.

[In France,] you have papers on the left, and they have a leftist point of view, and you have papers on the right, and they have a rightward point of view. And if you’re a reader, you can read both or you can choose which paper you read. But it’s not the job of Le Monde or Libération to explain to you the point of view of Marine Le Pen. It’s separated. People are partisan, and they’re not afraid to say so.

In Raw, I had no problem. We published artists who were absolutely not politically involved, and that’s fine. It wasn’t a political magazine. But we also published artists like Sue Coe. She had a specific thing she wanted to say in her work, which had to do with denouncing apartheid in South Africa.

[How to Commit Suicide in South Africa] was meant to be a pamphlet printed on newsprint, to have that kind of urgency. It had factual information, and we had very ardent discussions: “What is the goal of the book? What action do you want the reader to take?” I was really very practical in going at it. Feeling sorry for the people being killed—okay, that’s of some news—but what specific action should be taken? It ended up being about boycotting. The last spread is the list of the corporations that were invested in South Africa with a clear call for a boycott. It had a call to action.

I’ve been a small publisher all of my life. I can do what I want when I want. Even when the job [at The New Yorker] was offered to me, I thought, “Why should I want to work for somebody?”

Guernica: Plus, The New Yorker was so old-fashioned at the time.

Françoise Mouly: The New Yorker was very old-fashioned. To me, it was too sleepy and not challenging. When [comics artists] showed me their work and I wasn’t interested in it for Raw, I sent them to The New Yorker.

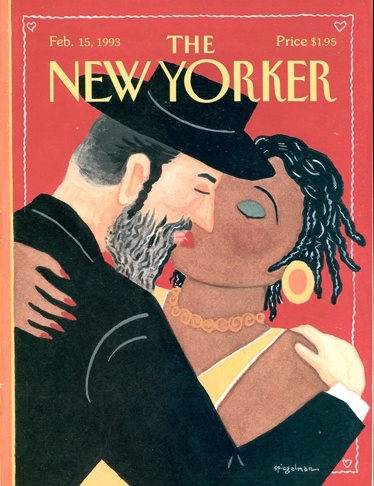

Art had done a cover, the Hasidic kiss. Tina Brown had loved this, which is part of the reason she asked me to become art editor. She wanted more of those provocative, engaging images. But that was resisted by everybody else on the staff, so when I walked in, it was a very embattled situation. She wanted The New Yorker to be at the center of the discussion every week and literally be the talk of the town.

When I was called in, it was open-ended. There was not a mandate. It was just, “Okay, jazz up the magazine.” For the covers of The New Yorker, I brought in a lot of people whose work got published in Raw. I kept discovering new people. A lot of people I publish now were the people I found in those first few years.

I did look at The New Yorker of the ’30s and ’40s, and those were a lot of storytelling images. I thought they were fantastic because they were narrative. They gave you a sense not just of how people were dressed or what the cars looked like but really of the fine-grain detail of what made them laugh, of their prejudice, of the trends that were going on at the time.

As with every magazine, it purports to be the upper class, but it’s also a reflection of what’s going on. You see shockingly racist images in the ’30s and ’40s because they were ambient—not because The New Yorker was any more racist, but because the culture was racist. You see blacks portrayed as cannibals. You see the GIs going overseas and the export of American culture in Asia. You see so many trends that are reflected in the covers.

Guernica: And what role does the cover artist or comics artist have in all this?

Françoise Mouly: The cartoonist accepts this mandate to communicate. The artists catch what’s in the air. It’s not because the artist “felt like it” or is a guru who channels the truth of the universe in some opaque, abstract way, or even in a realistic painting. The comics artist is someone who has the humility to set himself up in public culture and to communicate with the reader. If your image doesn’t make sense, it’s your problem, and I shouldn’t publish it.

They also feed off each other’s images. When I publish a good image, it goads other artists to send good sketches. They just want to go back to their drawing table and respond to that: “I’ll come up with my own thing!” Which is really necessary because—like the way it was thirty years ago—there are no other outlets for any of those cartoonists.

Guernica: At The New Yorker, you have published a lot of provocative, political covers.

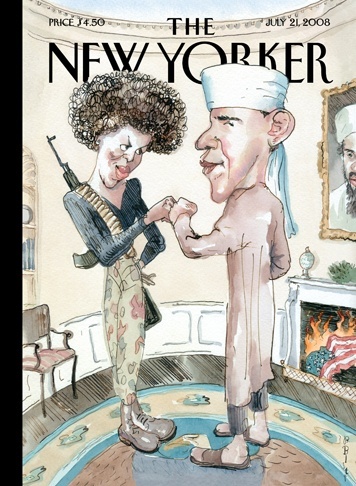

Françoise Mouly: At The New Yorker, I am working within the system that is given to me. I’m really lucky. I don’t have an editorial committee, I have just one person—David Remnick, the editor of the magazine. I’m really grateful that Remnick makes his own decisions. Once he does, he sticks by them—including when we published the fist bump cover by Barry Blitt.

We got denounced everywhere for that cover. “How dare The New Yorker do this?” And it was a good example of an image that was difficult to discuss. I would have liked to talk about it. David, instead, decided to go on the Wolf Blitzer show. He got called a Nazi by Wolf Blitzer, and his mom was watching. It was really a very vicious attack.

It’s satire. When you say it’s satire, people assume that the object of satire is shown. The problem was that the object of satire was implied and not shown. The object of satire was in the first sketch, actually, in which the right-wing pundits were looking in the window. My conversation with Barry Blitt was to show what they were whispering—the innuendo campaign when they were saying that he’s a Muslim, he was not born in America, he’s a terrorist, and so on. We wanted to show what they were talking about, and that is all that Barry did.

When you left them at the window looking in, it puts the blame squarely on Rush Limbaugh and Ann Coulter and those pundits. I still think that it was a lot more interesting to leave it unsaid. Because it’s too easy! It’s too easy to blame it on specific people. The phenomenon was far more deep-seated, and the proof of it was that when the image got published, it hit people viscerally, and they all came in denunciation and said to The New Yorker in an outraged tone, “I get it, I understand it, but I’m worried about my mother-in-law—she might not get it.” Well, this is just like the teenager in high school who’s going to the counselor saying, “I want to talk about my friend. My friend has a problem with his girlfriend.”

Now, this is about a picture that shows Barack Obama as a Muslim. There’s an American flag burning in the chimney, there’s a portrait of Osama bin Laden on the wall, Michelle Obama is dressed as Angela Davis with an AK-47. I mean, is this not ironic?

Time had to pass. Now it’s about seven years later. You can see how great this image was, in the sense that it inoculated the body politic. It was a little bit of poison, but it functioned like a vaccine. After that, Obama was the candidate. Until then, only Rush Limbaugh could get away with the innuendo.

The person who actually made a worthwhile comment on that cover was candidate Obama. His office denounced it before he even saw it. It’s clear to me that of course he understood the irony. How could he not? He ain’t stupid. But he did get interviewed that week on some TV news show and was asked about the image. He said, “The one interesting question that we should be asking ourselves is, ‘What’s wrong with being Muslim?’” Nobody wanted to have that conversation.

I’m not saying this from some kind of morally superior vantage point. That’s why I’m saying it’s not as useful to restrict it to, “Oh, the right wing is so racist.” I mean, we all have our own very deep-seated prejudices, and one of the things that these images can do is bring it to the surface and provide some kind of mirror.

Obviously, I can only operate within the confines of what David Remnick is willing to stand for and have a discussion about—especially because it’s on the cover of the magazine. People receive things as they are given: they do read it as “The New Yorker says this”—even though it’s signed Carter Goodrich or Barry Blitt or my name. Because it’s on the cover, it suggests that the rest of the magazine is implicated in what it says, more so than an article published inside by Ian Parker.

Guernica: Can you talk about TOON Books, which you founded, and the comics that you’re making for kids?

Françoise Mouly: I tend to want to publish things that don’t exist, that nobody else does. There are no good comics for young kids because nobody has ever bothered to do this before. I wouldn’t want to be in the business of publishing what I was publishing with Raw—independent comics—because there are plenty of people who are doing it just fine: Drawn and Quarterly and Koyama Press and First Second and so on. But I still feel like we fill a need. We’re doing everything we can to actually get our books in the hands of kids who don’t necessarily have parents who would be reading books to them at home. I’m more concerned about them getting good books. There’s still a sense of mission, of doing something useful, which allows me to still have a publishing business.

Guernica: It’s almost a populist approach to comics. With the kids’ comics, you’re offering visual literacy to these children who typically wouldn’t get it, and at The New Yorker, you’re making politically and culturally provocative art accessible to a massive audience.

Françoise Mouly: Yes, that’s far more interesting to me. I guess if you’re in the art world, then you know that so-and-so is doing this, and it’s in response to so-and-so. But for me—it’s not my field.

What I did with Raw—it sounds crazy to do this, but I was making sure that each issue of the magazine had a sense of the handmade. My first print run was only 3,500 copies and it grew to about 15,000 copies. Even then, we could do things like tear corners off, wrap things in cardboard, and so on. I liked that. I liked the mixture of mass-market availability with the handmade object. I liked the availability of the book. I liked, as you mention, the democratic process.

Even when I was publishing Raw, I really, really liked the fact that I would bring it to a store. I distributed it myself. I would put things on the rack, it was on consignment, and if people liked it, they bought it, and if they didn’t like it, then they didn’t buy it. It was a kind of trial by fire that I understood—and was eager for.

To contact Guernica or Grace Bello, please write here.