©Hayv Kahraman. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman gallery.

Iraqi artist Hayv Kahraman was ten years old when her family fled Baghdad during the Gulf War. They ended up in Sweden, where she spent her teenage years. Subsequently, she moved to Italy to study graphic design at the Accademia d’Arte e Design in Florence, and is now based in San Francisco. Her work has consistently dealt with female suffering in the Middle East, depicting delicate, beautiful women in moments of death, war, suicide, and depression.

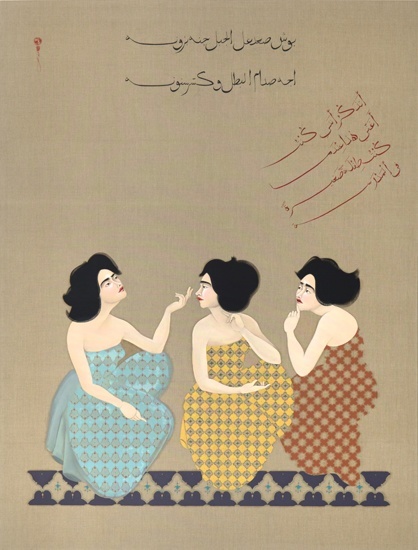

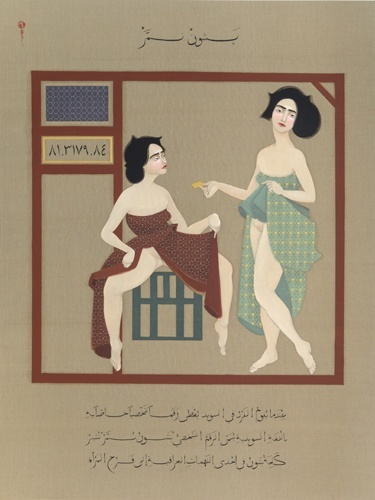

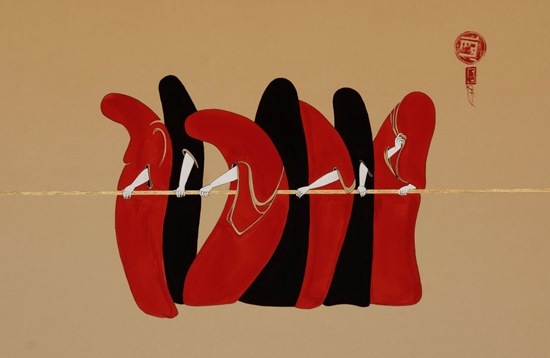

Her latest project, How Iraqi Are You?, currently showing at Jack Shainman Gallery in New York, offers a shift in perspective. Eight large canvases, each approximately 100 by 80 inches, present seemingly harmless scenes: women sitting in a garden, or talking together. Black and red Arabic script underlays and winds about the images. Kahraman is directly referencing the Maqamat al Hariri, a twelfth-century illuminated text that focused on the everyday life of Iraqis. But even when one cannot understand the writing, the paintings exude sadness, distance, and disconnect. By the entrance, the gallery has a translation guide for visitors. In “Broken Teeth,” the black script reads: “Bush climbed up a mountain like a pussycat up came Saddam the hero and broke his teeth.” The red script reads: “I remember that I used to sing this when I was a child in school.” In “Person Nummer,” in which two women are lifting their skirts, one offering a small piece of paper to the other, the black script reads: “When you arrive to Sweden you are given a personal identity number ‘person nummer.’ That is pronounced ‘peshoon nummer.’ In the Iraqi dialect peshoon means vagina.”

©Hayv Kahraman. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman gallery.

Distant memories, misunderstandings, and confusion present another kind of violence: one of childhood alienation and trauma. While Kahraman’s art is always intensely personal, her previous characters and their predicaments were universally and instantly recognizable. These new paintings reveal the invisible and psychological confines of fear, belonging, and culture; the limits of memory and time; and how forced displacement, while harrowing, can also create a strong and vivid inner self.

Kahraman’s work has been exhibited internationally—including at the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art in Kansas City, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and the Paul Robeson Center for the Arts in Princeton—and belongs to several public collections, such as the Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha and The Rubell Family Collection in Miami. I spoke with the artist via Skype and email, while she was visiting Florence with her seven-month-old daughter. She was ebullient and direct.

—Alex Zafiris for Guernica

Guernica: These works feel to me as though you are explaining something, or teaching.

Hayv Kahraman: Yes, that’s exactly what it is. Archiving my history. My daughter was born in the States—what kind of connection will she have to her Iraqi side? Much of it is personal memories that I want to pass on to her. My work is very research-based, and oftentimes when I delve into a subject, I randomly come across something else that I feel meshes perfectly. In this case, I was researching the Maqamat al Hariri, and someone posted a funny link on social media, “Test your Iraqiness.” A few weeks later, another person posted my work on a “Baghdad” Facebook page that has over half a million followers. The post described me as an Iraqi artist. The interesting part was the comments. Many said that I’m not “Iraqi enough” to represent Iraq, because I had left. My work has always raised questions of identity, especially since I fled when I was very young. I never developed a full sense of my own culture in the same way that my parents did. Wherever I lived after that, I was defined as the “other.” These works are personal narratives, but they are also a way for me to transcribe and archive a history that I feel I am forgetting.

When you are in an abusive situation, you don’t necessarily realize it, you don’t want to admit things to yourself. I was oblivious, not connecting my personal life to the work that was coming out.

Guernica: There is an inherent conflict in your body of work: about losing this connection, but also a strong distaste for the way women are treated in Iraq.

Hayv Kahraman: That would be somewhat correct. It’s not necessarily what I consciously focused on. It’s a subconscious thing. The work comes out, without thinking. My family was pretty open. I personally didn’t necessarily experience gender discrimination in that sense, but of course around me I would see things happening, and then I would relate. I was also in an abusive relationship a couple of years back. I didn’t know it at the time. I would see [violence against women] in the news, and I would feel immense empathy. My mom would ask me, “Hey, why all of a sudden this fascination with women?” When you are in an abusive situation, you don’t necessarily realize it, you don’t want to admit things to yourself. I was oblivious, not connecting my personal life to the work that was coming out. When the relationship ended, I started putting the puzzle together. At that time I was pushing the personal away. The gender issues, the feminine aspect of the work started then, when I was going through all these things. It was really cathartic and eye-opening for me, realizing, holy moly… It’s as if you’ve been sleeping, and you have just woken up.

Guernica: Given your heritage, and how it is often narrowly perceived in the West, your work has come to be labeled as activism. But was there a conscious drive toward that, at the same time?

Hayv Kahraman: Absolutely. Whether I wanted to admit the fact that I was very close to these women or not at the time, I was still consciously addressing these issues head on. I’ve always been an advocate for gender issues. My grandmother was actually one of the lead figures of the first women’s organization in Kurdistan, so the concept of equal rights was passed down to my mother, and then myself. What made the work go even further was my personal experience in an abusive situation that enhanced my response to gender discrimination I was hearing about from the media and my family in Kurdistan.

Guernica: These new works definitely appear to deal with trauma.

Hayv Kahraman: On many levels. The manuscripts of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries—among them Maqamat al Hariri—were created by the Baghdad school of miniature painting. These are beautiful illustrations, very different from the Moghul or Persian miniature paintings, as the emphasis was laid on the expression of the figures rather than a detailed background. Another amazing thing was that sexuality was prominent in these illustrations: we see examples of the main character showing his penis, as well as a full frontal view of a woman giving birth! Remember, this is at the height of the Islamic period. However, this quickly growing art form came to an abrupt end when the Mongols laid siege to Baghdad and destroyed countless historical documents and books. They say the waters of the Tigris turned black from the amount of ink seeping out of books flung into the river.

The commonality in these histories—contemporary Baghdad and thirteenth-century Baghdad—seems to be this overwhelming loss or trauma, and then the rebuilding of something new. For me, and many others in the diaspora at this point in time, it’s a rebuilding that stems from the margins, from a migrant consciousness of sorts. In thinking about depicting a scene from the ordinary life of an Iraqi, I needed to focus on the experience of an Iraqi immigrant or refugee, since this is my reality, but also [that of] 20 percent of the Iraqi population.

©Hayv Kahraman. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman gallery.

Guernica: I read that when you first moved to the States, you went through a depression, because it was the country that had hurt yours so much. You felt tremendous guilt, particularly as a free individual, compared to the women suffering oppression in Iraq. What kind of reading and research did you pursue during this time?

Hayv Kahraman: My main source of reference was the news. I would put it on and sit and listen for hours. I would then start researching a particular subject that I had heard about and start painting. So throughout the work it was constant news about what was going on in Iraq. This I think was a way for me to justify my existence in the West. The work served as an avenue to address concerns and actively do something about it. The works I did during that time were pieces on paper, like “In Line,” based on the self-immolation that was happening in Kurdistan, where women would pour gasoline on themselves and light themselves on fire because they couldn’t stand their domestic existence.

I can now see these Arabic letters from the perspective of an American or a Swede, and that terrifies me.

Guernica: Can you talk more about your use of the Maqamat al Hariri?

Hayv Kahraman: The process of writing the text into the works became somewhat performative, very much part of the work itself, since I was actively relearning how to write [in Arabic]. I didn’t want to copy blindly. I took my time to examine the original text, each letter, the thickness of the stroke, the shape, the angle. But I was determined not to force anything. I wanted it to be as natural as possible. I was relearning how to write, read, and speak my mother tongue. The tongue that I have forgotten, and don’t use anymore. The tongue I regret to have not continued to learn. I look at these Arabic letters with estranged eyes now. I was exported, and so was my language. But it’s also my fault for not having kept it alive. I was too busy learning the Western language and training my eyes to adapt to English letters. I can now see these Arabic letters from the perspective of an American or a Swede, and that terrifies me. It makes me want to reiterate them, paint them, write them, relearn them, and re-memorize them—recover them. I am trying to recapture my amputated mother tongue. At age thirty-three, I am searching for my nine-year-old self that spoke and wrote fluent Arabic.

The text in the manuscripts was written in the calligraphic “Naskh”—that is derived from “Naskha,” which means to transcribe or copy—and is a more fluid and fast script, often used to comment and transcribe the Quran. It was written in black ink with all the vowels and marks. The red text was added later as commentary often made during soirées in which the elite gathered to read the book and decipher the meaning. I wanted to implement some of the formal qualities of the old Maqamat, such as color schemes, structures, and composition. The frames engulfing the figures in some of the works are meant to represent certain architectural structures, like a house or a public building, or a school. Compositionally, the folios were divided with the text, either in the bottom or the top, with the image in between. These are all things that I’ve tried to implement in the works.

©Hayv Kahraman. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman gallery.

Guernica: Despite the subject matter, the images contain a very distinct feeling of clarity and control. There is structural and symmetrical logic. I know that you studied graphic design in Italy. Form and function seem to have a new resonance here—of containing and moving past these conflicts.

Hayv Kahraman: Yes! My process is very calculated and thought out. I know exactly what I’m going to paint before I even stretch my canvases. In these works I’ve used raw linen, which has a very specific tone. Interestingly, the tone and hue of the linen changes depending on the season, on the amount of sun and rain the crops receive. I’ve chosen a warmer hue for these works, and I have them shipped to me from Belgium. I then stretch my canvases and coat them with rabbit-skin glue. This seals the linen and creates a sheen. It’s important to spend time on this process, since the exposed linen is essential. Most of my works lack backgrounds because I don’t like to define contexts. I want the figures to be in constant flux; neither here nor there. I then do a lot of sketching and planning in terms of composition and color schemes before I start. Once I lay my first stroke, I know exactly what I want. There is some room for error, which I love, but also dread as I lose control! But the majority is predetermined. The only thing that is spontaneous is the pattern. This is somewhat intuitive, and I feel this is needed in the work. Perhaps because it reminds me of my home, and I feel that it creates a geometric order in the work. Living as a refugee I have found that I need to seek out placidity and order to survive.