Wheels and wheels and wheels spin by

In the spring that still is sweet.

But the flower-fed buffaloes of the spring

Left us, long ago.

They gore no more, they bellow no more,

They trundle around the hills no more:—

With the Blackfeet, lying low,

With the Pawnees, lying low,

Lying low.

—from “The Flower-Fed Buffaloes,” by Vachel Lindsay

Leather tunics, stone pipe bowls, fringed bags, beaded vests and gauntlets, painted parfleche envelopes, and rawhide drums; a bear-claw necklace and a war club carved in the shape of a deer’s leg, with an iron fang extending ominously from the head; dresses embellished with colored porcupine quills, and an upright feathered headdress, long and segmented and reminiscent of the skeletal remains of some magnificent bygone vertebrate.

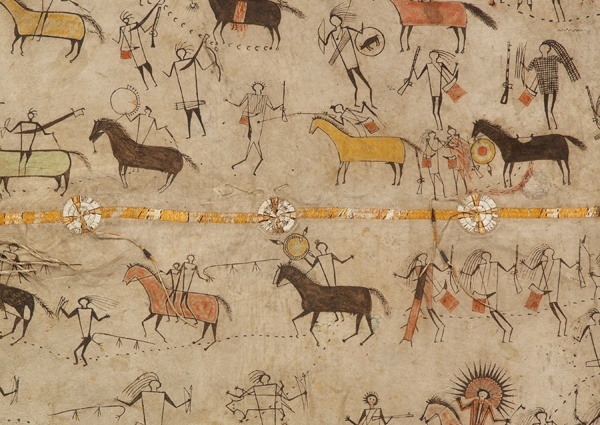

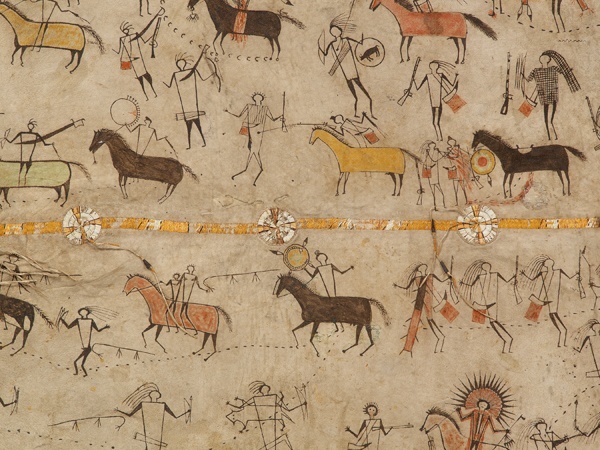

Objects such as these comprise The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky, which runs through May 10 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The exhibition arrives in New York from Kansas City’s Nelson-Atkins Museum, where it has just had a four-month run; before that it was at the Musée du Quai Branly, which co-published a beautifully illustrated catalogue with Rizzoli last fall. When I saw it there during a trip to Paris last June, it struck me that the heart and soul of this evocative show, if not also of the culture it represents—an indigenous American warrior culture that peaked in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries—were the painted buffalo hides. They are at once mystifying and legible, and stamped, as it were, with ancient configurations of life and death, man and beast, flesh and spirit.

A buffalo hide, especially an old one, is no ordinary backdrop.

According to the exhibition’s curator, Gaylord Torrence, the hides in this show are among the finest still in existence—“extraordinary works, and considered as such in the time in which they were made” by both Native Americans and European connoisseurs. There are eight total, six of them from European museum collections; the four belonging to the Quai Branly are among the oldest and date from circa 1700 to 1830. These works in particular exude something stirring, sad, and profound, and seeing them displayed together in their continent of origin is, as Torrence put it when we spoke, “really quite an extraordinary thing.”

The hides are robes, strictly speaking, but they are displayed fully stretched out so that they might be interpreted as if they were printed pages or paintings. The presentation alone thus places them somewhere between art and artifact. Torrence, a professor emeritus of Fine Arts at Iowa’s Drake University, prefers to show them “as close to vertical as possible.” The conservators, he added, preferred them to be laid flat, and the forty-five-degree display angle at which they’re being shown for this exhibition is a compromise. This seems right, in a way, for here are constellations of human gestures (figurative and abstract alike, as we shall see) imprinted in painterly manner onto a canvas—a scarred, weathered, once-living canvas itself that possesses all the character of an individuated object. A buffalo hide, especially an old one, is no ordinary backdrop.

The Buffalo Culture

Plains tribes embellished and employed skins of other animals, including elk, beaver, and deer. But nations like the Cheyenne, Crow, and Sioux did not build an entire mode of living around these creatures as they did the American bison; indeed, it is hard to overstate the buffalo’s centrality to their existence. “Seldom before in the history of mankind,” Tom McHugh writes in his excellent history The Time of the Buffalo, “had one species shaped the life of a people as totally as the American buffalo influenced the ways of the Plains Indians.” McHugh elaborates:

A story of the Utes and Lakotas told of the first humans emerging from the blood clot of a buffalo. In some Osage clans, young braves styled their hair to resemble the animal’s horns and tail. Shamans sought the wisdom of the buffalo spirits in their visions, and hunters imitated their behavior in sacred rituals. Found stones suggesting the humpbacked form of the buffalo were treasured objects, and the animal’s hardened dung served as fuel for fires. Men and women alike wore buffalo skins, whether or not they believed, as some did, that doing so would counteract the ill effects of a lightning strike or wolf bite.

Rather than become an object of fascination or worship in its own right, the horse reoriented tribal cultures towards the buffalo. It was, essentially, technology.

Spanish explorers observed this profound intertwining in their earliest encounters with North American tribes. “To be short, they make so many things of [the buffalo] as they have need of, or as may suffice them in the use of this life,” wrote the sixteenth-century historian Francisco Lopez de Gomara. His observations date from the end of the “Dog Days,” as the period came to be called. The Spaniards ended those days forever, when they introduced the horse.

Hides and Heroes

Rather than become an object of fascination or worship in its own right, the horse reoriented tribal cultures towards the buffalo. It was, essentially, technology. Like the bows and arrows that arrive courtesy of a benevolent creator in so much Plains Indian lore, and like the rifles that would come to succeed the early Europeans’ unwieldy muskets, the horse contributed hugely to man’s advantage over beast. They could haul collapsible hide teepees, enabling sedentary tribes to go nomadic, and switch from farming small plots to hunting big game.

Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

For the Sioux and other powerful tribes in particular, the age of the horse introduced unprecedented levels of ease and wealth. McHugh posits that far from bringing peace, the higher standard of living granted these nations “the luxury of waging almost continual warfare.” The horse undoubtedly introduced a new speed and sense of heroism to the hunt—no longer did men skulk around among the herds under cover of coyote skin. Men handled the business of stalking and killing buffalo, women much of the rest, notably the arduous but essential process of preparing the hides. The labor surrounding the animal was thus strictly divided along gender lines.

The same applied to painting hides. Women created only geometric designs. Among the established non-representational patterns is the “box-and-border,” a prominent feature on two hides that are in the Met show. One is from circa 1830, and identical to the one worn by a Lakota woman in a pencil-and-watercolor work by the Swiss artist Karl Bodmer. In the other example, the striped box sits in a glowing field of yellow pigment that is itself enveloped on a field of rich red ocher. But are these boxes purely figurative? They are now, in fact, thought to be an abstraction of a buffalo’s interior—a structure that women of the Plains tribes, who dealt so often with carcasses, would have known well. According to Torrence, the recurring geometric patterns “undoubtedly had associations. We just don’t know what they are.”

In their apparent modernity, or at least familiarity, the figurative paintings of the women contrast with the comparatively naïve pictographs undertaken by the men. (An exception here is an 1830 robe by the Mandan chief Mató Tópe, remarkable for its elegant figurines and hyper-precise sun motif.) Part of the suggestive power of the geometric works lies in their seeming removal from the anxieties and banalities of individual narrative. Men, on the other hand, used robes as records of their highest earthly achievements. And while these depictions were considered authoritative, they were employed as an accessory to oral storytelling, like slideshows accompanying a first-person lecture. In the whitewashed silence of the museum, with the original speaker long gone, there is a fundamental incompleteness about them.

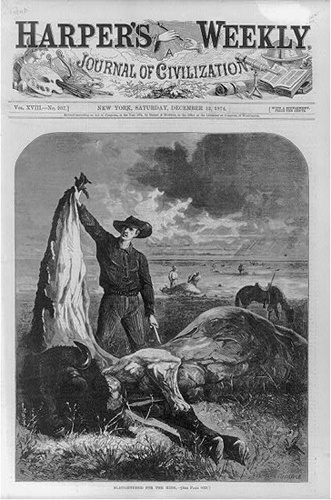

Plains tribes by this time were being moved onto reservations, and the industrialized massacre of the American buffalo was taking place. The senselessness of it all comes across in accounts of trigger-happy trophy hunters and of tourists who would take potshots into the giant herds without even bothering to get off the train.

The pictographic hides are, it must be added, the products of extremely selective editing. (Women artists, locked into their geometric patterns, were working under restrictions of a different type—a general suppression or subsuming of the self, we might say, rather than one applied to personal failings or misfortune.) These works bear a superficial resemblance to the so-called ‘winter count,’ a form of buffalo-hide calendar kept by the Kiowa, Lakota, and Blackfoot tribes. But the winter counts impassively recorded bad news. When asked, Torrence said that he knew of no buffalo-hide artwork that depicts defeat.

The Wasting of the Wild Plains

Torrence did, however, refer to a later work on muslin, which had become a more common medium than buffalo hides by the last decades of the nineteenth century. Plains tribes by this time were being moved onto reservations, and the industrialized massacre of the American buffalo was taking place. The senselessness of it all comes across in accounts of trigger-happy trophy hunters and of tourists who would take potshots into the giant herds without even bothering to get off the train. Sickening as they are to hear about, these casual killings amounted to very little compared to the destruction unleashed once the hide business hit full stride. As American and European tanneries developed better methods for treating hides by the 1870s, both the buffalo’s shaggy winter coat and lighter summer skin became de rigueur in the homes and carriages of any family that could afford them.

Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

Expert skinners could dispense with a five-year-old bull in five minutes. A hunter in Dodge City, Kansas boasted of killing 1,500 bison in one week. The Indian custom, of course, had been to waste no part, from lactating udders to the gallstones that were a source of yellow pigment. Even Buffalo Bill, for his comparative excess, had kept his men fed on buffalo meat. The industrialists left everything but the hide out to rot.

Plains Indian legends tell of an original, carnivorous, and more ferocious breed of buffalo that terrorized early man. Disappearing by the thousands daily, oddly unexcited by the sound of a rifle, and perversely drawn, hunters observed, to the sight and smell of their own dying, the buffalo was now the mirror image of that fearsome predecessor. Its absence from the plains around the turn of the century, when a small band of conservationists managed to salvage a tame herd and thus save Bison bison from outright extinction, would have flabbergasted all those early Europeans who grasped for metaphors that could convey the sheer enormity of the herds: fish in the sea, locusts in Egypt—or, indeed, a great robe spread out over the endless prairie.

Among the tribes, factory-made blankets had almost entirely replaced now-precious buffalo hides by the 1870s. Torrence estimates that there were “probably very few” painted hides left in native hands by 1900. Ledger art had replaced the older forms, and many works were being made with white buyers in mind.

There is something essentially unrecoverable at work behind the glass here.

Native Americans—some of whom took part in the hide trade—struggled to make sense of the buffalo’s disappearance. McHugh records that many insisted the buffalo had simply returned underground, from where the old myths said they’d first emerged. One can imagine the animals reunited with a vast treasury of hides that are not included in this exhibition. McHugh writes:

“Lying Low, Lying Low”

How, then, do any of these “splendid” hides remain at all? It is due to the wherewithal of a handful of European collectors and explorers. A few of the hides in the expedition are thought to have been collected in the first half of the eighteenth century at a French trading post near present-day St. Louis. Torrence suspects that they were robes reserved for special occasions, or perhaps commissioned by the French.

Among these is a remarkable Quapaw robe from around 1740. It shows warriors going into battle with bows and muskets, and on the opposite flank a group of men and women stiffly dancing. A symmetrical pair of peace pipes funnels from this scene into a tapered conclusion at the hide’s head. In the middle, a feather-and-sun motif mirrors a rayed moon, within which floats the outline of a human figure. Scholars don’t know what to make of this.

Another hide, by an artist from the Illinois tribe, perhaps, is almost entirely a mystery. Its central feature is an elongated Thunderbird of blade-like angularity. Assuming the artist meant to depict an upright bird, the hide’s head is facing right—an extremely anomalous orientation. The only other explanation, also unusual, is that the bird is plunging headfirst from the sky.

Up, down, left, right? On this animal envelope that has been adapted for a human, and that would presumably fit the body of an Indian or a European alike, the artist’s choices have scholars in disagreement about something as straightforward as the cardinal points. There is something essentially unrecoverable at work behind the glass here, to say nothing of those many individuals buried beneath the Plains in their ornamented robes.

The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky runs through May 10 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Darrell Hartman is a writer based in New York and the editor/co-founder of the website Jungles in Paris.