I have a confession to make to the proprietors of the Brasserie Cognac in midtown Manhattan: I stole a menu. The menu bears the words “Le thé n’est qu’une excuse” (“The tea is just an excuse”) and the accompanying picture is of an elegant continental blonde feeding confectionary into the mouth of a man in a turtleneck sweater. France. Romance. Food and drink as tools of flirtation. It all seemed so 100 percent James Salter and, since James Salter was the man I was waiting to meet, I claimed it as a memento.

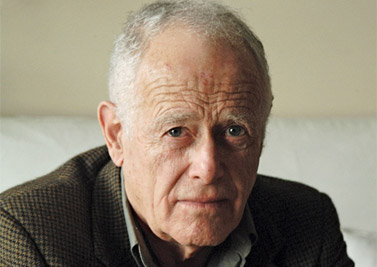

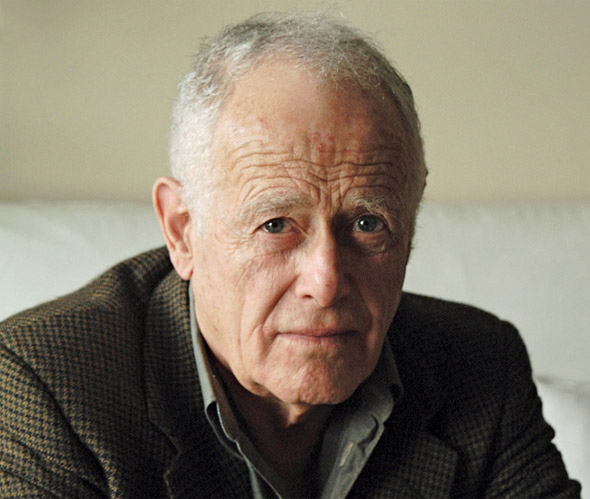

Would Salter have disapproved of my theft? It’s hard to know. He’s an intriguing combination of solemnity and playfulness, candor and manners. He entered the restaurant briskly, smart and only slightly stooped, a handsome white-haired eighty-seven-year-old man. There are lines written on his forehead and papery crinkles in the corners of his eyes, but he’s still thick-shouldered, powerful-looking, a former military man with a firm grip on my hand. Along with a handful of others, he has a good claim to being the greatest living American novelist.

When the waitress arrived at our table Salter’s eyes, custom-built to twinkle mischievously, twinkled mischievously. He asked her for some “tiny sandwiches,” and five minutes later some tiny sandwiches arrived. Macaroons, too. Miniature cakes. He doesn’t laugh easily (not at my jokes, anyway) but his lips always seem to be resisting a grin. He looks like a man struggling to contain some great indescribable amusement with the world. You sense a desire to make a pleasing impression, but also a resignation to the fact his statements may well be misunderstood. If you stumble upon a decent question, he is nodding well before you’ve finished asking it. Pick a more predictable topic and his eyes politely die as he reaches for more food.

All That Is, Salter’s new novel, is big in its ambitions, episodic in its structure, and written in prose which he told me is deliberately lacking in “ecstatic lines”, “showy” sentences, anything which “could be accused of being chichi and silly.” It’s a sad, hopeful work that beautifully evokes the pleasures and disappointments of a life lived in books, relationships, America. The prose may glitter less than in his previous novels, but you still know from the first pages that Salter is the author. “Vicky Hollins in her silk dress, the glances clinging to her as she passed.” Who else writes lines like that?

We talked about Zadie Smith (he liked her recent New Yorker story, “The Embassy of Cambodia”) and then we talked about Sarah Hall (he admires The Beautiful Indifference, and wrote her a letter to tell her so). When I switched on my recorder he leaned forward a little in his chair. Halfway through the interview I heard a man at a nearby table whisper “Who is that guy?”, but Salter, if he heard this, ignored it.

—Jonathan Lee for Guernica

Guernica: How did All That Is start its life?

James Salter: I think I probably began several other books first. I don’t mean that I started book after book in succession, but I toyed with—considered—various novels I thought I might write. And I finally saw that what I was really trying to write was a book about the life of book editors, of publishing. It’s a subject I’ve been interested in for a long time. I’ve been an observer of the business for years—more than that, of course, since I’ve known editors not merely as editors but as good friends. So All That Is began with that impulse, the impulse to write about a life in books. And at some point I realized I wanted to make it broader than that. I didn’t know exactly how. I spent a couple of years just filling notebooks.

Guernica: You said in a Paris Review interview in the early ’90s that you like to go into a new novel “with a lot of ammunition.”

James Salter: Yes, in an echo of my supposedly colorful past… I still like to make a lot of notes. During the couple of years I was filling out notebooks for All That Is, I had nothing definite except a one-page outline of a life. That life changed slightly. At one stage he was married. He had a couple of children. He was a slightly different figure in a slightly different life. When I’m filling notebooks I’m trying to pin down what I’m really interested in and to find those details that are so hard to come by, details that I can look at and believe are right on the mark. Things which bring a novel to life. They can take a while to come. [Smiles] Unfortunately a big point has been made that this is my first novel in thirty-some years, so that’s been everyone else’s first question: why did it take you so long to write this? Why did you wait thirty-four years? And those really aren’t the right questions. I know they make sense, but I can’t give a really satisfactory answer when I’m asked. I get asked those questions much more often than I get asked about the title, for example.

Guernica: What does the title mean to you?

James Salter: Well, you’re a writer, so I’m sure you know that these things—while interesting—can be difficult to explain. But let me try to answer my own question. There are at least two ways of looking at the title All That Is. One of them is that for Bowman, the pages are “all that is”—all that is his life. And in another way, it’s not his life, but all that there is in life generally, in any of our lives: a series of moments, of relationships. Neither interpretation is exclusively right, but I suppose together they explain why I felt it was the right title for the novel.

Guernica: There’s a moment in the book when Bowman, after a failed relationship, talks about what’s “judged inessential” in a life. That line had a resonance for me because this felt, at times, like a novel which sets out to rescue everyday “inessential” things from being forgotten—giving fragile, daily moments a beauty, a place on the page. That says: these things are essential, they’re all there is.

James Salter: Yes, can I see your copy? [Reads the relevant paragraph.] That was meant purely in terms of the relationship—he cannot understand how something that mattered hugely to him could turn out not to have mattered equally or at all to her. Something tremendously important to him has been judged inessential by her. That was all I meant, but I see that it does have a wider resonance. All the moments that would be lost if they weren’t set down. It’s not something I had in mind when I wrote it, but I see that it stands well for certain elements in the book.

The truth is I became a little self-conscious about people telling me how much they loved my sentences… With All That Is I decided to modify myself a little bit… I didn’t want to write ecstatic lines that were going to get in the way or annoy—consciously or not—the kind of reader I wanted to attract.

Guernica: The first book of yours I read was Light Years, which also concerns this idea of what’s remembered and what’s lost. The language of that novel is quite different to the language of All That Is. It feels like in this new novel you’ve taken a conscious decision to—I’ll use a bad metaphor—dim the wattage a little bit. The prose is less dazzling, and I wondered if that was a deliberate decision. A different lighting which brings out different elements of character and story rather than individual sentences, rhythms.

James Salter: Yes, it was a deliberate thing.

Guernica: Can I ask why?

James Salter: I suppose the truth is I became a little self-conscious about people telling me how much they loved my sentences. They’d come up and say, “You know what, I’ve memorized lines from Light Years.” At book signings you’d see them with the corners of pages turned down, particular pages they’d loved and sentences they’d underlined. It’s flattering, but it seemed to me that this love of sentences was in some sense getting in the way of the book itself. And perhaps I also had in my head the fact that the first critic who wrote a big review of Light Years said it was “chichi,” a “silly” book, words to that affect.

Guernica: This was [Robert Towers in] the New York Times.

James Salter: Yes, the New York Times. At the time, that review was wounding. I thought, “It wasn’t written to be chichi, or silly, so this must mean that I am essentially chichi and silly, and that I am a writer of chichi, silly books.” Anyway, I was sensitive to that thereafter. I don’t mean morbidly sensitive but, you know, it was on my mind. After a year or two you move on and say “All right, that’s happened.” But the criticism remained in my consciousness and I didn’t want to write a book that could be thought of as being chichi and silly again.

Guernica: I loved Light Years. It has its die-hard devotees, many of them other writers. It’s surprising to me that a review—however wounding—could affect how you felt about your prose style. In the UK the book is now a Penguin Modern Classic, a rare thing for a living novelist, and is published with an admiring introduction by Richard Ford.

James Salter: [Smiles] That introduction is better than the book. But no, with All That Is I decided to modify myself a little bit. I don’t mean changing my writing in a serious way, but I was crossing out some of those sentences that stood out, that were more showy. I crossed out some of the things which seemed to me excessive. I didn’t want to write ecstatic lines that were going to get in the way or annoy—consciously or not—the kind of reader I wanted to attract.

Guernica: What kind of reader do you want to attract?

James Salter: Sometimes I write with a particular person in mind. I think it’s fair to say that I write for a perceptive reader. You have to get it. If you don’t get it the first time you may not understand. If you like repetition, analysis, explanation, you probably won’t like my books.

A writer writes a book. People read it. You don’t know what they’re reading, really. You read a review and think, “That is so inaccurate. You can’t have been reading my book at all. You can’t have been reading it with any kind of attention, because that is all wrong, that’s even the wrong name you’re including there.” But, you know, these reviewers, generally speaking, have been diminished in importance, the work is so little respected. If you’re reviewed by a real critic, by James Wood or Louis Menand, then you get something that is informed, interesting, and highly articulate. But the average review doesn’t have that kind of depth anymore.

Only the things written down have any gravity to them. The other things are ready to disappear.

Guernica: You mentioned relying on readers to draw inferences from a single line or paragraph of your prose. Do you think there’s a trend in American fiction towards novels which go the other way, working by accumulation and repetition? The layering of detail upon detail over the course of 500 or 600 pages to achieve psychological realism. A reader is told a lot more about a Jonathan Franzen character than he is about a Salter character.

James Salter: Amplitude is a powerful quality in fiction. It results in involvement, in sympathy with the characters. After a while, a reader can’t avoid being involved with a book, caring about it, even if it’s not a particularly good book. You’re in it, and you’re committed to it.

Guernica: Could you say a few words about the epigraph to All That Is? “There comes a time when you realize that everything is a dream, and only those things preserved in writing have any possibility of being real.”

James Salter: This refers to the summation of life, in the same way that the title does. In the end, it finally all seems to have been a dream. Only the things written down have any gravity to them. The other things are ready to disappear.

Guernica: Late in the novel Bowman thinks of himself as “not related to other people—his life was another kind of life. He had invented it. He had dreamt himself up.”

James Salter: I think what he meant by that is that he was inventing, and was aware of it, his ultimately false, glorious life with this woman. It did not really exist, he discovers. Not as he pictured it. But there’s the paradox. How does one explain it? Can a relationship be non-existent after his having lived it, believed in it, for several years? Does it cease to be real simply because it fell apart? No. But it’s still been proved false, in one sense.

I’ve written about this before in a story called “Comet.” In that story a woman complains that she’s discovered her husband has been having an affair for the last seven years. She’s going to have to rethink those years, she says. But how can you rethink them? How can you rethink whole years of your life? You’ve lived them. And as much as you may come to think you were living false years, they were perfectly true to you at the time.

Guernica: Bowman is born in 1925, in New Jersey, and has a military background. He has these things in common with you. Is it helpful, when building up characters, to take some of the basic architecture of your own life, or of the lives of other people you know, and to start from there? Does it free you up to then invent the details which you mention are essential to your fiction, the ones which add that special ingredient which Saul Bellow called “esprit”?

James Salter: That was a great phrase of Bellow’s. It explains it all, really. But as for whether it’s a helpful thing for me to take elements from my own life, you could make a case for it, but I don’t think you could prove it. I was born in New Jersey, but I left when I was a year old and the state has not meant much to me in my life since then. I picked New Jersey for the character of Bowman because a friend of mine who was an editor and writer came from Summit, New Jersey. I’d never been in Summit, and didn’t even know where it was. But the name was intriguing to me, and I thought, “why not?” I appropriated it for the novel. Of course, I then had to go to Summit. I got to know it very well.

Guernica: It makes for a good chapter heading at one stage in the book. The word “Summit” surrounded by white space.

James Salter: Yes it does. And there’s an actual diner in Summit, New Jersey, which people think Hemingway wrote about in one of his stories [“The Killers”]. But it turns out that he wasn’t writing about a diner in Summit, New Jersey. He was writing about a diner in a different town: Summit, Illinois. But Bowman doesn’t know that—his youthful literary ignorance is illustrated in a number of ways at the beginning of the book. He’s naïve.

As for having Bowman be in the war, I felt I had to do that, and it comes down to something Christopher Hitchens said. He made a remark once that struck me. He said that no life is really complete that hasn’t seen love, poverty and war. I thought, “That’s very succinct.” So the war and the love part I could relate to, and I kept it in mind. I wasn’t in the Navy, as Bowman was; I was in the Air Force. My personal experiences were nothing like Bowman’s.

Guernica: You mention Bowman’s naïvety. Was it important to you that he should lose that over the course of the book, that the novel should trace that process?

James Salter: I think he loses his naïvety, yes. Midway through the book, he’s got to a point where he’s able to handle himself very well in company with writers, with women, with friends. He ceases to be naïve. But I don’t believe he ever becomes more than an intelligent, relatively stable man satisfied with his work and with his life. I don’t believe he’s seeking himself, or any such thing. If you haven’t found yourself by the time you’re forty… Well, actually, I guess a lot of people haven’t. Bowman is intelligent and mature but not cunning, not shrewd, not aggressive. You’d like to know him. In fact, I did know him.

Guernica: You knew him?

James Salter: Not a specific individual, really. I simply meant he’s modeled after people I’ve known.

Guernica: The novel starts at war, in battle, and from there moves toward more intimate, private moments in Bowman’s life. You give a sense in these pages of the publishing industry back then as a somewhat quiet, genteel, intimate profession.

James Salter: It did interest me that publishing was a genteel profession back then. Perhaps not quite as genteel as we think it was, but probably more so than it is today. The book doesn’t really go into this point, but many of the publishing houses then were privately owned, a single publisher or a publisher and a few associates who were responsible for everything. They could take whatever risks they wanted, could essentially publish what they liked according to their taste. Publishers today are working for big corporations. They have different pressures. I don’t think they can make decisions quite as independently as they used to be able to. They have more corporate and financial responsibilities weighing on them. They’re not free to go broke or go to jail.

Guernica: Maybe we can talk a little about A Sport and a Pastime. It’s another novel that deals with the intersection between reality and the imagination; the narrator drops hints that his own account is at least partly fictitious. It was your third novel, but you’ve said before that it was the first “real book” you wrote. Why so?

James Salter: Well it seemed to me that A Sport and a Pastime was the first novel I wrote that didn’t have amateur touches. Touches that are purely technical: how to use conversation, how to attribute conversation. How to interweave thought, supposition, actuality—to put them together at the same time. I felt I was able to do that really for the first time in A Sport and a Pastime, or at least for the first time with any authority. To do them and make them invisible, unknown to the reader. I think that’s what changed with A Sport and a Pastime. I became better at making my technique invisible. I felt I was writing well.

Guernica: Was there anything about the reception of A Sport and a Pastime that surprised you? Perhaps the level of eroticism people seemed to find in it?

James Salter: It’s still an erotic book, even in these advanced times. There’s nothing in that novel that high school students aren’t texting to one another. And there’s no shocking language in it, not any longer. There might be the word “fucking” once.

Guernica: Just once?

James Salter: I think so. I can’t recall. And—yes—there’s the word “prick,” and “cunt.” But these only appear when they’re meant to have an effect. I think A Sport and a Pastime has a purity to it, its tone. It’s a book deep in that time of life when nothing but love seems to be of importance to you. Most people go through that period at some point. That’s really what the book is. It’s an act of reverence. It doesn’t mean to be any more than that. It should make you a little envious, perhaps, but that’s all.

Guernica: In The Paris Review book Object Lessons, Dave Eggers calls your story, “Bangkok,” “a nine-page master class in dialogue.” The power of that story and some of your others comes almost entirely from speech.

James Salter: Generally speaking I tend to like dialogue that has some reason for being there, that tells you something. In a lot of books people talk and they’re not interesting, merely talking about things that are inconsequential. Personally, I prefer dialogue that tends to have a reason for being there.

Being somebody: it’s one of the ideas in life, no? That’s what my father made clear to me. The importance of being somebody. He wanted to be somebody. And he underlined to me the fate of trying to be somebody and not quite managing to do it.

Dialogue’s a method of revelation, of course. A few words of dialogue can reveal worlds about a character. I thought Dave Eggers was very perceptive about “Bangkok.” I thought he picked out essential things. For example, somewhere about a third of the way into the story the woman says to the man “Tell me something, Chris.” And as Eggers points out, it’s a rather soft, civilized name compared to Hollis, the man’s surname, which he’s been called by until that point. And we suddenly have a different notion of who the character is, and who she is, and of what has passed between them.

Guernica: Has any of your work writing for films been enjoyable, or helped to inform your fiction?

James Salter: I don’t know. I always say “no,” because of my lack of any real success in films. I had films made, but they weren’t as good as I anticipated. But of course films are dialogue, so you’re writing dialogue continually. I suppose you learn something by writing it over and over.

Just writing things down on a page didn’t make me feel like a writer in the way I’d felt like a pilot. And meanwhile everyone was going on with life, especially the people I knew and had served with. I felt very powerless and lost in those years. Futile is the word. Complete futility.

Kathy [Zuckerman, Deputy Director of Publicity at Knopf] was talking to me today about the new Julian Barnes book, in which he writes about being up in a hot air balloon. I haven’t read the book, but when I was asking Kathy what the relevance of the air ballooning was in a book which I’m told is about grief, she indicated that the reader comes to realize he was inferring, with that image of being up in the balloon, a broader point of view. A sense of perspective. Seeing the earth in a different way. Usually when I’m asked if being a flyer has influenced my writing, I say “not much.” But listening to Kathy today I thought maybe I’m not giving flying its due. You become accustomed to a very different scale of things, up there. You pay attention to things you don’t normally pay attention to. Perhaps flying did have an impact on my writing. I don’t really know.

Guernica: Were there times, after you left the Air Force, when you regretted having done so?

James Salter: Yes. Every day. For a long time, every day. I wasn’t really a writer yet. And I didn’t know how to become one. Just writing things down on a page didn’t make me feel like a writer in the way I’d felt like a pilot. And meanwhile everyone was going on with life, especially the people I knew and had served with. I felt very powerless and lost in those years. Futile is the word. Complete futility. You go from being a kind of aristocrat in the Air Force to being, as I said in The New Yorker, a nobody on a bus. If I wanted to be somebody, I had to start my life again. Being somebody: it’s one of the ideas in life, no? That’s what my father made clear to me. The importance of being somebody. He wanted to be somebody. And he underlined to me the fate of trying to be somebody and not quite managing to do it.

You write for glory. You play for glory. There’s an ambition to excel, isn’t there, to be a star? To score more, to do more… Writers want to be read. They want to be admired. And they want to be known, I would say.

Guernica: Your writing offers perspectives on seco just out of reach. It’s something discussed by Vernon Rand in Solo Faces, and also Viri in Light Years. Then there’s a moving moment in Burning the Days where you describe your father lying “in bed in the city he was meant to triumph in.”

James Salter: Well it seems to be recurrent with me. In climbing, being first-rate is part of the whole enterprise. The important climbers want to be the first man up the mountain, the one who put up the first route. You’re usually only remembered if you put up the first route on a very important climb. The route might even be named after you. That’s a kind of glory.

Guernica: Do you write for glory?

James Salter: We all do. You write for glory. You play for glory. There’s an ambition to excel, isn’t there, to be a star? To score more, to do more, even when it’s a team sport. So I think striving for glory is a natural subject for a writer. Seeking fame. I think Viri puts it well when he says in Light Years that there’s no greatness without fame. Writers want to be read. They want to be admired. And they want to be known, I would say.

Guernica: Immortality?

James Salter: You would have to be very optimistic to think that any of your books will be among the books that survive in the very long run. I think if a writer is lucky enough to still have a few books around after he’s gone, a few that are still being read, then he’s accomplished quite a lot.

Guernica: “Write or perish.” That’s something you’ve often been quoted as saying.

James Salter: Oh, that was a stupid thing to say.

Guernica: Was it?

James Salter: [Laughs] Oh God yes. The really stupid thing was the “perish.” I’d given up everything to be a writer, and if I didn’t then go on to do that—to write—then I didn’t know what would happen to me. That’s all I really meant to say, but I got carried away by some kind of poetic impulse.

Guernica: Without spoiling the ending, do you think Bowman has, by the last pages of All That Is, come to terms with the sweep of his life? That it wasn’t, perhaps, all he at first imagined for it?

James Salter: I think he’s content. He’s with a woman, and he talks about whether they can have a life like the lives in art, by which he means the lives of painters and sculptors, lives on a different level from yours or mine. In place of getting married, that is, which he feels he is too old, too used-up for, perhaps. But meaning to stay together always. And he says that he wishes he could introduce to her to his past, have her somehow able to share in the past, things that have happened to him, and they are going to go on together, in immediate terms to Venice as they’ve talked about but only vaguely. I think he’s bound for a long happiness, but naturally some reviewers and readers will decide otherwise.

Guernica: And what about the lives of books? There’s a line towards the end of All That Is where you write that “The power of the novel in the nation’s culture had weakened,” but that, nonetheless, “fresh faces kept appearing, wanting to be part of it.” Your character thinks publishing has “retained a suggestion of elegance, like a pair of beautiful, bone-shined shoes owned by a bankrupt man.”

James Salter: It seems to me that literature is giving way a little bit to the immediacy of other diversions, other forms of entertainment. What will it be in fifty years? I don’t know. Will there be printed books? Probably, but I’m not sure. There’s always going to be literature, though. I believe that. I think literature has a way of getting deep into people and being essential. Literature has its own powers.

To contact Guernica or James Salter, please write here.