By Angela Boskovitch & Laura Silvia Battaglia

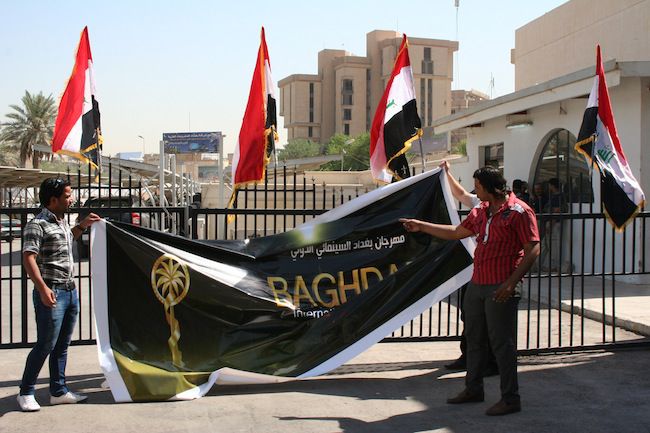

Of all the words of reportage and opinion that have been printed about Iraq since the 2003 U.S.-led invasion, few have been reserved for the arts. Destruction of the country’s museums and cultural institutions has led to the loss of irreplaceable antiquities as well as film archives, creating a kind of artistic desertification. The Baghdad International Film Festival or BIFF, the fourth edition of which was held October 3-7, is part of an effort to break the city out of this recent cultural isolation.

There were tanks in the streets, but the audiences never stopped coming.

The festival was founded in 2004 by Taher Alwan and Ammar Alarady, professors in the cinema department at Baghdad University’s Academy of Fine Arts. The inaugural festival was held in September 2005 in the Almansour Hotel, during a time when sectarian violence had reached horrifying levels. “On the opening day of the festival in 2005, Baghdad saw some 20 or so car bombs,” recalls Alwan, who serves as the event’s director. “All of Baghdad was under occupation and there were tanks in the streets, but the audiences never stopped coming for a chance to attend Iraq’s first film festival.”

Before 1991, Iraq had 275 cinemas, but the international embargo following the Persian Gulf War prohibited filmmaking equipment and celluloid film from entering the country, so no new Iraqi films were made. Students at the Academy of Fine Arts continued studying film, but movies would be made on video instead. After 2003, what remained of the dwindling industry was almost completely destroyed. An especially dark day came on August 1, 2007 when the Semiramis Cinema, a theater that had been a Baghdad landmark, with three levels of red velvet seating for 1,800 viewers, closed its doors and was transformed into a porn den, as were many other abandoned cinemas across the city. Today, there isn’t a single cinema operating in Baghdad.

Although Iraq’s first movie theater was established in 1919 and its first long fiction film screened in 1948, events saw to it that the country never fully developed its cinema industry. “Since the 1940s until now, we’ve not made more than 100 fiction films,” explains Tariq Aljoboury, who’s written extensively on cinema in Iraq. “Non-professional filmmakers became involved in the film industry. With the coming to power of the Baath Party in 1968, the government built many cinemas, but as in any dictatorship, they used cinema for their own goals. Iraqi cinema today needs funding and an infrastructure.”

For those attending the closing ceremony at the Ishtar Sheraton hotel, the festival was also an infusion of the glamour that has been missing from the city—jeweled dresses, trophy ceremonies and the ever-present flash of lights

With the necessary investments, Iraq could develop an internationally competitive cinema industry, like the one that thrives in Jordan, thanks in large part to the Royal Film Commission of Jordan. “It’s not only the money that’s missing and the lack of cultural activities like the festival, it’s also the lack of professional education,” explains BIFF jury member Dirk Van dan Berg, a filmmaker based in Germany who’s worked on projects in Africa, the Middle East and Central Asia. Together with another member of the jury, Van dan Berg met with several young filmmakers during the festival to workshop their film projects. “One young person we met with wants to do a short film about why he’s forgotten so much of his past. These young guys just don’t know how to get their ideas into a film script that will then become a film. That’s the really difficult part, and there’s not a sensibility for this yet.”

For those attending the BIFF closing ceremony at the Ishtar Sheraton hotel, which included actors and directors from Iraq and beyond, the festival was also an infusion of the glamour that has been missing from the city—jeweled dresses, trophy ceremonies and the ever-present flash of lights. Just how needed this creative energy was in a country that’s suffered as much war and trauma as this one was palpable. As quickly as photos were snapped, they were uploaded via smartphone to personal blogs and Facebook pages. International guests were frantically sought out by young bloggers to give interviews about their experiences in the country.

“This event is in part about bringing the glamour back to our city that it deserves,” says Alwan, who worked around the clock to see the event took place despite the obvious challenges, most notably the fact that outside of major hotels, the city lacks venues with the necessary security and reliable electricity. Nearly a decade after the invasion, Baghdad continues to suffer constant power cuts that interrupt daily life for hours at a time.

Another major challenge the organizers face is that the festival has never been included in the government’s budget. Large companies in Iraq have no tradition of sponsoring cultural events. Alwan explains that BIFF’s budget is “that of a small village festival in Europe, not nearly enough to organize a major international film festival. This means we can’t afford to invite film critics and filmmakers whose films are screened at the festival to attend.”

Despite all this, the screen still goes up and the event goes on. “This was the largest edition of the festival in comparison with previous years and we’re very pleased,” says Alwan. Sixty countries participated, and the festival featured a new cooperative arrangement with the Clermont-Ferrand Short Film Festival in France. This collaboration meant that the BIFF had access to award-winning films from the past three editions of the festival, from which more than ten were chosen for screening in Baghdad.

Each year the BIFF also features a country as guest of honor and this year’s was Mexico, with over 30 Mexican films shown. In all, the BIFF screened more than 300 films—considerably more than the 120 screened at the last festival— all organized by the independent Iraqi-registered NGO No Border Iraqi Cinematographers. The organization includes graduates of the Academy of Fine Arts and some independent filmmakers; in addition to organizing the festival, the NGO also organizes workshops focused on film, to develop new talent.

Iraqi filmmakers have to confront themselves with the level of cinema that’s out there in the rest of the world. That would create more conversation between the Iraqis and everyone else.

To encourage the young generation of filmmakers, the BIFF New Horizons category screened 25 films made exclusively by Iraqi filmmakers. The Iraqi films dealt largely with themes of war and conflict in Iraq, often by examining them through social issues and the way in which society has been affected by the near daily violence. Many of these films seem to have incomplete scenes, or are perhaps too direct and raw in their treatment of violence.

The decision to have an all-Iraqi category was critiqued by some. “This is something I’d change if I were in the Baghdad Film Festival,” explains Van den Berg. “Iraqi filmmakers have to confront themselves with the level of cinema that’s out there in the rest of the world. That would create more conversation between the Iraqis and everyone else. I hope that there’s going to be more exchanges like this in the future.”

The winning New Horizons entry, Another Side by Bqir Jassim Alrubaie, however, is unique in that it looks at how the violence that has engulfed the country has somehow entrapped everyone. Though short, the film is powerful: it manages to show in 15 minutes how all sectors of Iraqi society have had to take part in the country’s shared nightmare.

In response to having won the prize, which caused the audience to take to its feet and erupt in screams of jubilation at the near end of the award ceremony, Alrubaie expressed mixed sentiments, “I’m really happy to have won this prize, but I think I speak for all Iraqi filmmakers, especially young ones, when I say we need more festivals. We need more events. And we really need cinemas in Iraq again.”

Twenty-two-year-old Nawras Safaa, herself an aspiring filmmaker, definitely agrees. The 2012 graduate of Baghdad’s College of Fine Arts recently made a film for her graduate-level project about how Iraq’s sectarianism has destroyed the country’s families. “I had good enough grades upon finishing high school to go into any profession. I chose art and cinema because I love film so much, but we young people have no opportunities in this field here. We’re really suffering, staying at home just losing our time and our futures. I feel we’re so far behind other people our age around the world.”

The role of the government in supporting the development of the film industry and young filmmakers in particular was discussed in the BIFF International Forum on Iraqi Cinema. On occasion of Baghdad being named the 2013 Arab Capital of Culture, an Arab League initiative that’s part of the UNESCO Cultural Capitals Program, the Department of Cinema and Theater in the Ministry of Culture is pledging some 12 billion Iraqi dinars ($10.3 million) to bolster the film industry, including the production of short films, long fiction and documentaries.

“I think the Ministry of Culture is making a good investment here,” says Alwan. “We should be optimistic, but we need to encourage the ministry for annual support. Although not that many young filmmakers will be supported with these funds, at least there’ll be film production happening again in Iraq, the first time since 2003.”

The Arab Capital of Culture event is prompting the Iraqi government to make other investments in cultural infrastructure as well. Construction is underway on an 87,000 square meter Grand Cultural Complex that will house a 1,500-seat opera house and a building for National Symphony Orchestra rehearsals. The Culture Ministry is commissioning museums, public libraries, theaters and art galleries for renovations, and 19 new statues, monuments and memorials will be built across Baghdad to highlight the city’s cultural heritage and to mark late artists and cultural icons. One such statue, a 21-meter-high monument that will depict Mesopotamia’s many civilizations, is planned for the spot where Saddam Hussein’s figure stood in Firdos Square until it was toppled in April 2003.

All of these investments will mean little, however, if the security situation does not allow for the return of art and cultural activities. Despite the wave of conservatism, the need for activities to engage a restless young population—the Baghdad citizens who are likely to don Western fashions and hairstyles and carry a smartphone—is particularly evident. After nearly a decade of war and civil conflict, Baghdad is a divided city of concrete walls, barricades and checkpoints, where artists and cultural venues have come under devastating attacks; but it is also a city with artists and cineastes, looking to reverse that trend.

Angela Boskovitch is a freelance journalist, writer and editor focusing on topics related to the young generation, development and arts & culture. Her writing has appeared in ARTPULSE (USA), Christian Science Monitor (USA), Women’s eNews (USA), On Earth (USA), The Egypt Monocle (Egypt), The Austrian Times (Austria), FRM-FrankfurtRhineMain (Germany) and DEUTSCHLAND (Germany). She has conducted interviews for various documentaries and also edits the website, www.Young-Germany.de aimed at the young global generation. She also creates and works on art and culture projects for social development in the Middle East, and is developing an Art Center to be located in Egypt. She has also lectured university students in communications at the Provadis School of International Management and Technology.

Laura Silvia Battaglia is a foreign correspondent with the Italian daily Avvenire. She also works as a freelancer with the weekly Terre di Mezzo, the news agency Redattore Sociale, the radio networks Radio Popolare and Radio In Blu and with the rolling news channel Rai News 24. She is senior news editor of the website assaman.info, which focuses on the experience of Senegalese immigrants in Italy. She has produced reportage from conflict zones around the world, including Lebanon, Israel, Gaza, Afghanistan, Kosovo and Serbia. She attempts to recount “the other” through writing, music and images. She won the 2010 Giancarlo Siani award with her video “Maria Grazia Cutuli.” Il prezzo della verità” and was a finalist for the 2010 Anello Debole and Claudio Accardi awards with her video “Sassi tra gli ulivi”. In the last two years, she has covered first-hand the revolutions in Egypt and Libya, the presidential election in Senegal, the Syrian conflict, and political and social issues in Iraq and Iran. Since 2007, she has also taught a course in the Masters of Journalism program at the Catholic University of Milan.