Miscellaneous Files is a series of virtual studio visits that uses writers’ digital artifacts to understand their practice. Conceived by Mary Wang, each interview provides an intimate look into the artistic process.

During my conversation with Anelise Chen, she asked me why I had picked up her 2017 novel, So Many Olympic Exertions. The autofictional book follows Athena Chen, a graduate student who is struggling to write an American Studies thesis about sports. Recognizing that readers of literary fiction aren’t necessarily interested in sports writing, the author suspected I was one of them.

She was right. I have long despised all sports, with what I saw as their off-putting display of testosterone and disregard for beauty in service of efficiency. Yet reading Exertions made me realize that I actually live like an athlete: I see my work as a game I could win or lose. Writing, to me, is a painful expenditure of energy—my chances of success are minimal, and that success is only reachable through a continuous, punishing effort that wouldn’t look out of place in an athlete’s training schedule.

Exertions is less about sports than it is about the question of why we expend effort on things that have such little obvious value—whether it’s playing sports or making art—and, really, why we keep going at all. “From above, swimming looks effortless,” Chen writes. “With no visual cues to indicate distance gained or heights ascended, it’s easy to forget the fatigue concealed in the feat. It’s easy to forget that water is a weighty medium that requires tremendous strength to push through. It’s only up close that you can hear the ragged breath, the arms stroking wildly against the clock.”

Elements of Chen’s current book project—a memoir told from the perspective of a clam—can be read on The Paris Review’s blog The Daily. As the website’s “mollusk correspondent,” Chen has published explorations of the phylum through the lens of art history, geology, and climate change. The project got its start when, “after a rib-bruising bike crash caused by momentary inattentiveness and conditions of reduced visibility (sobbing while cycling) the mollusk had briefly succumbed to an episode of hysteria, during which her mother kept texting her to ‘clam down.’” Chen’s identification with her mother’s serendipitous typo propelled her investigation into a new set of questions: What causes us to retreat in our shells? What is the cost of opening up?

At a bar in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn at the end of the year, Chen and I spent an early evening discussing what she calls the “What’s the point?” problem—one that has plagued athletes and artists alike. Scrolling through folders of photos and videos Chen had collected, we discussed the pain of pursuing art, the arbitrary rules we abide by in both sports and life, and how writing and reading function as self-help.

1. “If someone is going to spend their whole life becoming a curling champion, then writing a novel isn’t that bad.”

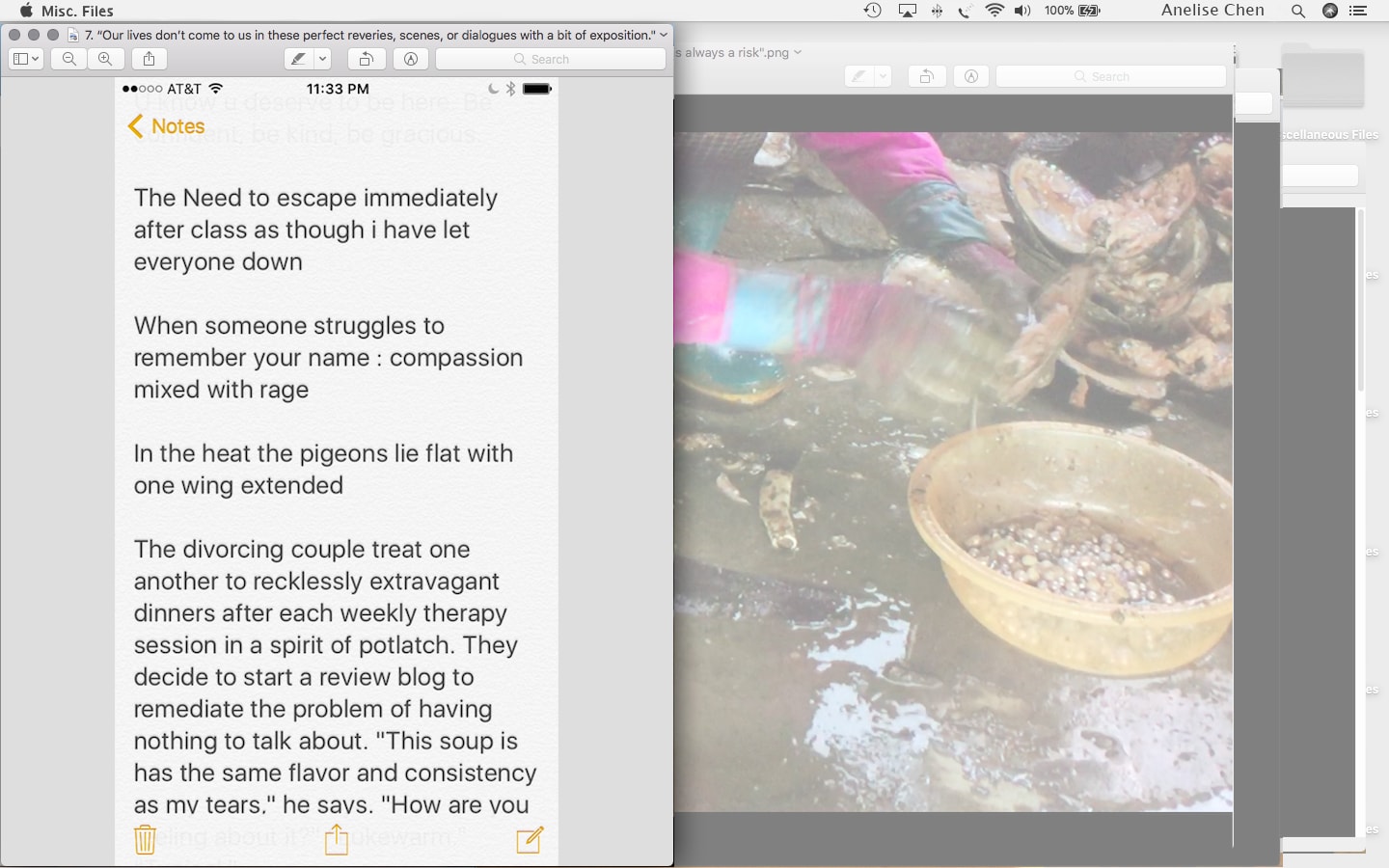

Chen: This is from a book of cycling exercises. One man is riding on another in cycling position, while doing calf raises.

Wang: Why does this person have to sit on another person to do this?

Chen: That’s why it’s so good! Maybe it’s about team-building. There’s something metaphorical about it. When you’re riding in a pack, whoever is riding at the front has to work harder to help their teammates at the back. Maybe this is literally what it feels like to go up those hills?

Wang: Tell me about the process of writing Exertions.

Chen: It was a very mysterious process to me. I had never written a book, so I didn’t know what I was looking for. I just followed my gut, and my gut was telling me to collect a lot of weird sports photos.

It all started when I was watching the Vancouver Olympics in 2010. What the athletes were doing was just so beautiful: their contortions, postures, and expressions. There are so many expressions that flash across the athlete’s face in a short period of time—joy, sadness, shame—so there’s a lot of drama.

I went to any sporting event I could go to, and tried to figure out why I was so captivated, since I had no interest in it prior. I hate the professionalization of sports, the culture around it, and the hyper-competitiveness. It’s an activity that seems to inculcate the tenets of capitalism.

Wang: I had no interest in sports prior to reading this book either. I often forget that I even have a body. I could be perfectly happy living as a brain in a jar.

Chen: But we don’t live as brains in jars, though.

Wang: Which is why I often get into trouble.

Chen: I was so out of touch with my body when I was writing Exertions. Maybe this investigation into sports was a way to get in touch. My students often write stories about disembodied brains, and I ask them, “Where is the setting? What is the body experiencing at this moment?” We inhabit physical space, even if we forget because we’re on our phones all the time.

Wang: The book is more about sports logic than the sports themselves. Reading it made me realize that I abide by its logic in my daily life: I’m wedded to this narrative of winning versus losing, and I maintain a stubborn faith in the value of effort and persistence.

Chen: We’re all in the game, and we’ve all agreed to a set of rules to play by. But is it possible to invent other games? Games and contests are made up of arbitrary constraints and delineations—they simply present us with attainable goals, so we can feel a sense of reward when we reach them. But I question what the game is and why we’re all playing it.

Wang: In that way, it’s a parallel to the artistic endeavor. We operate within institutions that tell us how to practice art, even though it’s essentially undefinable. And these goals define whether you’re a writer, and how good you are.

Chen: Making art and playing sports are very similar, because there’s very little instrumental value. You do them for their own sake, and it’s hard to justify what they’re for. That’s the other hurdle I was trying to get over—while writing this book, I was trying to convince myself that I could do this activity that felt so useless and meaningless. So the investigation into sports was a way to persuade myself that art itself is worth pursuing. If someone is going to spend their whole life becoming a curling champion, then writing a novel isn’t that bad.

2. “I wondered whether we’re condemned to think in this cost-benefit way.”

Chen: The ski jump is a complete act of faith. I really love that Werner Herzog documentary, The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner. It seems impossible that this person isn’t bound by laws of gravity: when they’re in the air, it looks like they’re flying.

Wang: The book starts with an anecdote about an Olympic speed skater who falls during a race, because he heard just moments before that his sister had died of cancer. Six years later, he wins a gold medal and hoists aloft his newborn child, who is named after his sister. You write, “The lesson here seems simply enough. Even after disaster has roiled through and left us immobilized on ice, we can still choose to keep going.” I do always ask myself, “Why do I keep going?”

Chen: Or, “If I can’t keep going, what’s wrong with me?” That’s a big question I had, too. Quitting is so shameful in our culture.

Wang: You once said that everything you read is self-help. The synopsis of Exertions says the book has elements of self-help, too. Did it help you?

Chen: It did. I was going through a difficult time. The question of suicide comes up again and again in the book. Perhaps the book is also a long meditation on whether or not to keep going.

One of the first sections I wrote was about this problem Athena suffered from as a child, her “What’s the point?” problem. What’s the point of doing anything if it will always, eventually be undone—if entropy is the default conclusion? She had to come up with these very complex rationalizations. Why should I clean my room if it’s just going to get dirty again? You see where that line of reasoning leads. I myself had a constant running ledger calculating energy expended and profits gained. I wondered whether we were condemned to think in this cost-benefit way. But writing the book cost me so much effort that, after it was done, I decided that expending effort was enjoyable for its own sake. I stopped asking myself what it was all for—I just tried to feel its worthiness moment-to-moment.

I learned a lot about patience too. People are often shocked when I tell them it took me six years to write this book, because of the book’s relatively short length. But the text is only a tiny portion of what actually went into it. I had to live. I had to change as a person, and learn how to be in a different way.

3. “What did Kafka do?”

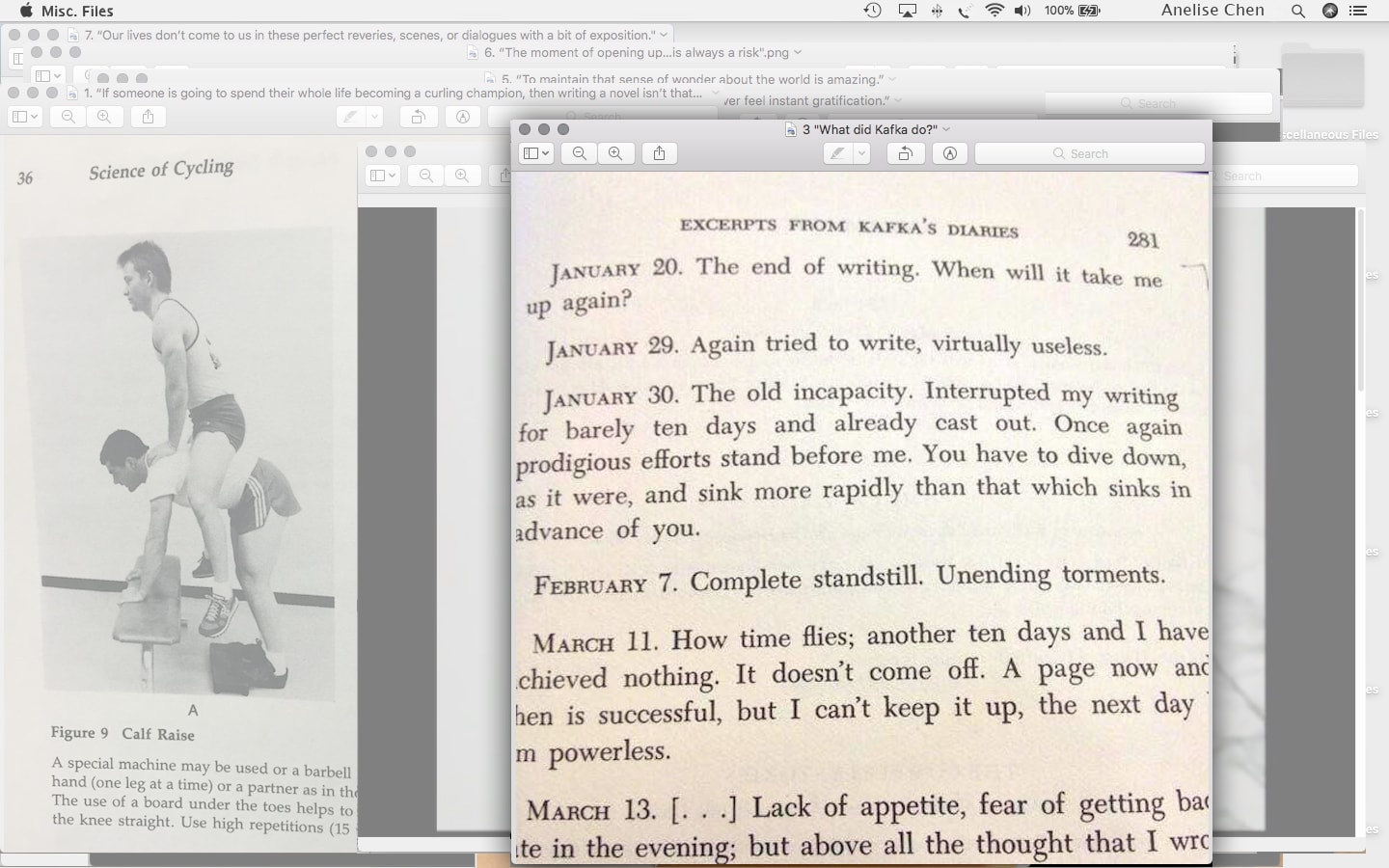

Chen: I was finalizing the proofs for Exertions on the day I took this picture, and I was trying to write too. I must not have been having a very productive day, because something compelled me to pick up Kafka’s journals, which are always extremely edifying. I thought this was so funny, because he’s not able to write. That really resonated with me. This is another manifestation of the self-help book: What did Kafka do?

Wang: This reminds me of how Leslie Jamison often says the problem of the essay can become its subject—she attributes that to Charles d’Ambrosio.

Chen: Diaries are such a good place to record failure. That’s what diaries are for. I wanted Exertions to feel as if it wrote itself. A diary is a present-tense book—you don’t get to record an entry until you live out the day. I was thinking about what that would look like in novel form, where things seem as frustrating and scary, because you don’t know the future.

Wang: The book talks a lot about habits and routines. You write in the acknowledgements that Exertions was mostly written in Bobst Library and Coles Gym. Do you have a routine for writing?

Chen: I really needed that routine. Routines are a way of locking the future down. We can’t know the future, but if you have a routine, you sort of do know. It’s a constraint that liberates you, because it dampens some of that anxiety about the future. I imagine it’s the same thing with poets who might feel liberated working within a certain rhyme scheme or poetic form.

I don’t really get to have a routine for writing anymore, though. I try to block out my days, so that half of the week I’m just teaching and the other half I’m just writing. But over the summer, when I have long chunks of time, I have a rigid routine. I don’t use an alarm clock, but I try to wake up as early as possible, and I’ll write until noon or so. And then I’m done for the rest of the day, and I have to do something physical and move around.

4. “I hardly ever feel instant gratification.”

Wang: You called the folder that contained this photo “Misery While Writing.” Are there certain things you do to offset that misery?

Chen: I take pictures of myself while writing—pictures of myself being miserable. Perhaps it’s what childbirth feels like: no one can feel your pain except for you! There was a period during which I often resented my ex-spouse, because he couldn’t share my suffering. One day, he said, “It doesn’t even seem like you’re trying very hard.” But that’s because others can’t see what you’re going through from the outside—this kind of mental anguish is very private, but very intense.

Wang: My spouse is an artist. But even though we have a basic shared understanding of what that effort is, we also work with different media, so we often can’t see each other’s efforts because they’re practiced in such different ways.

Chen: Aren’t you envious of artists? They get to be so embodied, and they can be a lot more intuitive. I dated an artist for a while, too, and he would say, “Just show up in front of the canvas and see what happens.” He told me about a useful John Cage quote: “Do not try to create and analyze at the same time. They are different processes.” But actually, I don’t think that’s how it works with writing. At least, not for me. I think writers have to toggle between creation and analysis much more. I need to experience the insight before I can record it. I need to know roughly what I’m trying to say before I can say it. Otherwise it’s just nonsense.

Wang: When you work with other media, whether it’s film or paint, there’s often an instant gratification you can get from seeing its beauty. With writing, there’s only you and the computer. There’s no instant gratification coming from anything but yourself.

Chen: Yes, so writers have to learn how to deal with that. I hardly ever feel instant gratification. You get so little feedback when you’re writing a long-term project. That’s why I sometimes have to take pictures of myself, for myself, as an act of witness. I’m acknowledging my own suffering.

5. “To maintain that sense of wonder about the world is amazing.”

Wang: I love this video of your mom.

Chen: My mom is my hero in so many ways. She’s endlessly curious and fascinated by everything. She’s in her sixties, so to maintain that sense of wonder about the world is amazing.

This was her first time seeing snow. She’s such a child here, walking around, touching the snow. You have to do this as a writer—to really open your eyes and appreciate things.

I’ve been thinking a lot more about my parents because of this new book I’m writing, a memoir from the perspective of a clam who wonders why she is the way she is. It’s about liberation from constraint, fear, hopelessness, and futility, and about putting yourself out in the world to form a meaningful connection. I started because, when I was separating from my partner a few years ago, my mom kept texting me to “clam down.” So I started thinking about how, if I’m a clam, then surely my parents must be clams too? I must have inherited these traits from them.

6. “The moment of opening up…is always a risk.”

Chen: This is a video piece by the artist Mika Rottenberg, called NoNoseKnows. It shows a pearl cultivation factory in China, where they’re sowing pearl oysters to get them to make pearls. Then their pearls are gouged out and dumped in giant heaps. It’s horrifying. You’re mass-producing a precious object, and you’re forcing these animals to perform this labor against their wills. It’s so representative of how we treat the natural world, this surfeit of beauty that we take for granted.

Wang: Part of your writing on this subject appeared on The Paris Review Daily, where you were the “mollusk correspondent.” How did this project come about?

Chen: I was already doing a lot of research on mollusks when the then-editor of The Paris Review Daily approached me about a column. You know, so many people were obsessed with shells at some point in their life. This fall, I was doing research about Darwin and his eight-year barnacle obsession, during a period when he was extremely fearful about what he was doing, before he went public with his theory of evolution. So he retreated into his shell, and started writing about these shelled animals. We have all these idioms—”retreating into your shell,” “coming out of your shell”—it’s a very intuitive feeling. But we’re so out of touch with the natural world that we rarely see the relationship anymore. What can we learn about adapting and surviving from other, non-human beings?

Wang: You describe this book as a memoir from the perspective of a clam. How did that form materialize for you?

Chen: The form finds you. I tried to write this book in a more conventional way, thinking that I would write a bunch of first-person essays about mollusks. It didn’t feel good to me, and I tried writing in the third-person, and it still didn’t feel right. Then I changed it to third-person clam, and that was exactly how it was meant to be. The novel was the same: I didn’t set out to write a book of fragments that resembled a journal. It just happened organically.

7. “Our lives don’t come to us in these perfect reveries, scenes, or dialogues with a bit of exposition.”

Chen: When I’m traveling, I usually take notes in my Notes app, though most of the time when I write, I take notes in my notebook. My sister and I used to have a blog called Chen Sisters Looking at Things. I’m fascinated by what people notice, and everyone notices different things.

Wang: You describe the book as “hypomnemata,” a Greek term for the notes-to-self form. What is your attraction to that form?

Chen: It’s an ancient Greek practice that the Stoics later adopted to encourage this kind of note-taking, where you’re reminding yourself how to be virtuous—like personal accounting. A lot of my notes-to-self are motivational messages, or about processing something I felt ashamed of.

I read so many diaries and notebooks when I was writing Exertions. I love the form, because all the layers of literary convention and posturing are stripped away. It’s so immediate; you feel like you have direct access to a person. So when you’re taking notes, it’s like having direct access to yourself.

There’s this Zadie Smith essay where she talks about what realistic fiction would look like. She writes:

“But is this really what having a self feels like? Do selves always seek their good, in the end? Are they never perverse? Do they always want meaning? Do they not sometimes want its opposite? And is this how memory works? Do our childhoods often turn to us in the form of coherent, lyrical reveries? Is this how time feels? Do the things of the world really come to us like this, embroidered in the verbal fancy of times past? Is this really Realism?”

Our lives don’t come to us in these perfect reveries, scenes, or dialogues with a bit of exposition. A lot of novelists have described “novel-nausea,” this disgust with fiction as a form. Somehow, for me, the note-taking format mimics the feel of daily life in a truer way.

Wang: Plot and structure can feel oppressive, because they force you to take on this authority that you might not want. You wonder, “Why do I have to make things make sense?”

Chen: And why do things have to build to a climax? And why do things always have to be in conflict? I’m less interested in grand, sweeping plots, and more interested in the minute movements a mind makes from moment to moment. Life feels very chaotic and orderless, and with the note form, you feel that someone is actively trying to figure something out in the moment. There’s a certain tension to that small struggle that I find extremely worthwhile.