1.

The glass collector rises at low tide. The beach closest to the city is best, and the most dangerous. Bums sleep and fight there. Married men find each other against the rocks and are quick to hurl bottles at anyone who catches them. The glass collector brings a knife, a flashlight, a canvas bag, and a radio that he attaches to his belt loop. Sometimes he listens to a baseball game and sometimes to the classical station.

Early morning: the plaza swept by street cleaners, the copper roof of town hall against a sky the color of oyster shell. The glass collector crosses the plaza, walks the empty road and down narrow cement steps to the beach where tourists are afraid to go. Tourists prefer the beaches owned by hotels. The locals help keep it this way; the glass collector once lived with a woman who made driftwood sculptures and terrified the tourists. She would hunt for the driftwood on the beach, dressed in rags she had braided together. She carried branches the color of bone, her hands filled with so many splinters they seemed to be made of wood. She told tourists she was a witch, a word that meant one thing to them and an entirely different thing to the islanders. She never tried to explain the difference.

Years ago, the sculptor left the island to sell her driftwood in Chicago. She returns twice a year and leaves with suitcases stuffed with bleached wood. Sometimes she phones the glass collector and sleeps for a week on his couch, sometimes in his bed. She tells him, What you’re doing is insane. You’re insane.

This morning, the beach is deserted save for the homeless men who sleep in hammocks they’ve strung up between palms. The glass collector sometimes gives pastries and coins to the homeless; it is because of them the shore offers more glass than shells—their discarded bottles roll into the ocean, are shattered and sanded by the water.

He turns on his headlamp and begins to search. It does not take long. By sunrise his bag is heavy. By noon, he has put a handkerchief around his neck to shield his skin from the sun. He leaves soon after, his bag filled. He has fifteen teardrops—this is what he calls the small blue shards—and hundreds of larger pieces, amber and sea-foam, one that spans nearly four inches and is perfectly flat. Later he will return with a new bag and take whatever the other collectors have left behind. Local artisans use the glass for cheap jewelry they sell to the tourists who disembark from cruise ships and want to buy quick souvenirs. The glass collector does not deal with tourists. He is making something he will never sell.

He constructs the glass mosaic in panels that stretch to the ceiling of his studio, housed in a former monastery with wooden beams across the ceiling and chipped floor tiles brought from Spain. The mosaic tells the story of the island, a history that begins with rainforest, palm trees heavy with coconuts. The second panel tells of industry, rows of sugarcane made from tawny glass, a cluster of workers with raised machetes. In the third panel, the glass collector told his own history; he had pieced together the bed on which he was conceived, the brother who died as an infant, the daughter who lives in Minneapolis, the snow that blankets her city. The renderings are imprecise, limited to the colors of bottles.

The last time his daughter visited, he showed her the first panel, which he had just completed. He had her cover her eyes as she entered the workroom. Her mouth was prepared to smile, to tell him it was beautiful. But when she saw the panel, her hands drifted slowly to her sides.

What is it?

It’s the rainforest. You were born ten miles from there, on your grandmother’s farm.

The glass collector pointed to the parrots, the glossy leaves the size of his palm, the drop of blood from handling a piece of glass that had not been fully sanded.

I’m glad you’re keeping busy, his daughter said.

When the glass collector showed the driftwood sculptor his sketches, she’d said, No one will buy these; they’re not even pretty enough for tourists.

The women in his life—his daughter, the driftwood sculptor, his ex-wife in Miami—did not care for his work. But each time the glass collector entered the workroom, shaking off sand from his boots, he saw the finished panels leaned against the wall and felt as if each were a door he could walk into. He thought this was enough.

2.

The tooth was resting on a rock, as if a crab had carried it there. At first the glass collector thought it was a stone or a wad of dried gum. But he bent closer to the tooth, lifted and inspected it. He wondered if there had been a fight, or if it came from a skeleton in a sunken ship, the tooth knocked loose by the currents and carried here. He thought to hurl it into the ocean, but he was accustomed to taking whatever the ocean might offer. He pocketed the tooth, adjusted his bag.

3.

What the tourists want: hand-rolled cigars, straw hats of varying craftsmanship, mojitos, shot glasses printed with decals of the island’s flag, vacuum-sealed bags of coffee harvested in the island’s fertile inland, t-shirts that say Island Living and No Pasa Nada.

Recently, the glass collector has been noticing a change in the tourists. Thirty years ago, they were honeymooners and families. They stayed for ten days, as recommended by their travel agents. Their faces would briefly become familiar; the glass collector passed them in the plazas, in the city’s historic district. They would wander up and down the streets, stopping for coffee or chilled glasses of beer with extra lime. By the end of their stays, the tourists assumed a fragile belonging, a kind of benevolent arrogance. He would hear them say, “Let’s get coffee at our place,” meaning a café where the glass collector’s grandparents had taken him each morning before school, where the tourists had gone enough times to recognize their waiter. It didn’t bother him that the tourists felt they had seen everything worth seeing on the island. He thought of them as neighbors, the way his grandmother thought of the ghosts that occasionally passed through her living room, taking sips of water, sighing loudly, then vanishing. The glass collector smiled at the vacationers so they would think the islanders were friendly. Maybe they would remember that kind, smiling man. Maybe some day they would come back.

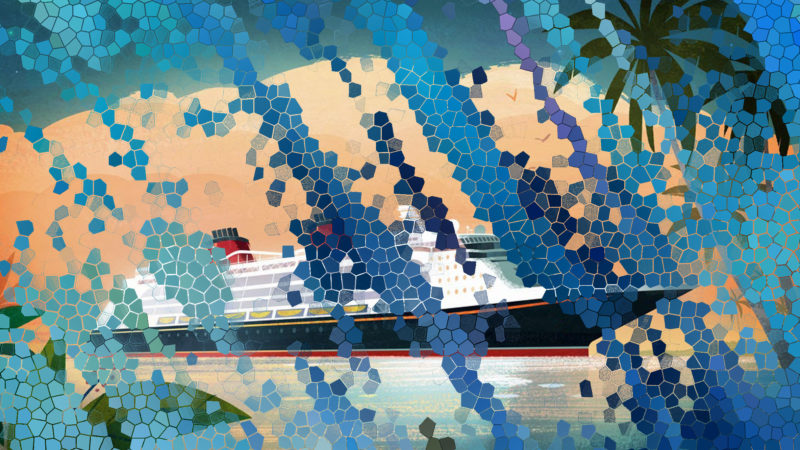

But now the tourists come by cruise ships, stay only for the afternoon. They are frantic to see as much as they can, to buy enough souvenirs to compensate for their limited time. The local artisans know the cruise schedule, and when the ships arrive, they set up their stands in the plaza close to the port. Everything they sell is Original! Authentic! Local! They paint tiny renderings of the city’s landscapes and monuments on shells taken from the beaches. They sell hand-strung ukuleles. They craft fountain pens out of native wood, sell terrariums of pilfered moss and stones encased in glass. A few men dress as pirates and charge tourists for photographs, or let them pose with rain-forest birds on their arms, birds with wings whose colors do not exist in the places the tourists are from.

4.

The cemetery is close to the sea, adjacent to the slum whose corrugated rooftops are painted lemon, tangerine, zebra stripe. The cemetery was once the resting place for Spanish soldiers, but once the Spaniards left, the islanders buried their own dead in raised marble tombs.

The first grave robber smashes in the tomb of a child and steals the jawbone. Soon, the glass collector sees tourists wearing necklaces made of baby teeth set in gold. The artists huddle and theorize at the market, wondering who could be selling the teeth. Some of them suspect it was a tourist who smashed the grave. Others wonder if another artist did it. They eye the glass collector, suspicious of the man who takes sea glass but doesn’t sell it, doesn’t seem to do anything at all. They wonder if he could be a genius at commerce.

5.

The glass collector returns from a 2 a.m. low tide with his heavy bag, and the artisans are waiting for him in the plaza. The cigar maker holds him down while the others search his pockets. The glass collector shields his face; he expects them to rob his bag, swing at his jaw until a tooth dislodges. His tooth a necklace, his tooth a silver ring. But instead they find the ocean tooth he has kept in his pocket. They take it as some kind of proof, then leave him there, his bag spilled and glass spread wide around him, as if something has broken and shattered right there, right then.

The next day, two more graves are destroyed. When the cruise ships arrive, the artisans sell finger-bone earrings, human jawbones as instruments. The tourists decorate themselves with dead islanders, dead Spaniards.

They look like cannibals, the glass collector tells his daughter on the phone.

You need to leave that place, she tells him. It makes people crazy.

She does not ask about his work, so he tells her about the changes he will make to the next panel. Instead of a panel on immigration, he will create an homage to tourists. He will show them getting off their boats. He will show them crowded in the plazas. He will show their jewelry boxes in New Jersey and Florida and Wisconsin brimming with teeth.

6.

The police do nothing about the grave robbers. The glass collector suspects they’re getting kickbacks from the bone vendors. But one afternoon, a tourist leaves his hotel with scissors, and he cuts the braid off a young woman on her way to the university. The woman cries in the street, calls him a madman. Her boyfriend punches the tourist across the mouth. But by the arrival of the next ship, the artists are selling their own hair around shells, woven with fishing line, portraits and cityscapes made from single strands.

7.

The glass collector avoids the plaza during the day. Instead, he spends all day combing the beach. He tells one of the homeless men about the new business, and the man’s eyes glint with promise.

You think they’d want these? he says, opening his mouth.

You can’t pay for a roof with that, the collector says. He regrets telling the man. He runs his tongue over his own teeth. It is not poverty or desperation that drives the grave robbers and artisans. He understands this. It is possibility; it is the flattery that the tourists offer. The ordinary body is a storefront, with price tags on each bone, each strand of hair.

What will they do, the man says, when all the graves are empty?

Maybe, the glass collector says, they will buy something else. Or maybe they’ll find a new island.

8.

His daughter and wife had left the island because they said it was shrinking.

Everyone’s gone, his wife said. There’s no use.

His wife and daughter wanted mainland television channels and mainland politics; they wanted apartments whose lights didn’t go off once a day. They thought of the island as isolated, adrift. But the glass collector knew something different. An island is an island, yes. It is solitary and its inhabitants may be walled in by the ocean, but an island is also a magnet. It pulls and pulls, drawing in wreckage from the sea: bottle shards, crab skeletons, ships as large as city blocks. An island, the glass collector had always thought, is the center of the world.

9.

The sculptor calls from Chicago.

Is it true? she asks. I’m seeing people wearing teeth around their necks.

The glass collector ignores her, tells her about his newest mosaic. His fingers are scuffed and cut, and he is only an eighth of the way through the panel. He has sketched out the cruise ship with its thousand windows, the tourist who cut the girl’s braid, the man on the beach pointing to his open mouth. The glass collector wishes he had kept the tooth from the artisans, so he could place it in the center of the panel. But he knows it has already been sold, so he reconstructs a tooth from glass.

It’s a disease, the sculptor tells him. You can’t see how bad things are getting. You just have your stupid mosaics that don’t look like anything at all.

They’re living, he says. They are alive here, in my house. I can hear them breathe.

You’re playing with broken bottles, she says.

10.

These are the permutations of love: He loves his wife even though they have not spoken in six years. He remembers how he asked her to return to the island, how desperate he once was to convince her that he was worthy of her love, that he was capable of returning it. He loves these imagined conversations because they pain him.

He loves the sculptor for how she has become her art, transformed herself into something that comes to shore and waits for someone to recognize the beauty of its contours. He loves the island because it birthed him, and because it is not a safe place: the sky is menacing before a storm; it unleashes rain as if in attempt to drown the island, to tuck it beneath the ocean.

Of course he loves the sea glass; he loves how it washes on the sand, unspeaking, reticent about whatever it saw below the waves. How the glass returns to the island, presenting itself as a gift. How it resists his panels, how it curves away from the story he tries to tell. He loves the lost tooth. He chooses to love the artisans, to love their infatuation with cruise ships, how they bend to the will of the tourists. He even loves the tourists. They are not trying to colonize the island, but the opposite. They are looking for ways to carry it with them, to bring the island home.

You are, the driftwood sculptor tells him, unbearably naive.

11.

The next time he sees the ships arrive from his window, the glass collector drags the first panel from the studio. This takes some maneuvering; he calls for his neighbor, an art student, to help. They lift the panel and slide it out the door, then walk down the hill to the plaza, where the glass collector leans it against the base of a statue. He leaves Christopher Columbus to guard the mosaic, then he and the art student return for the second panel, the third, the half-finished fourth. They align them next to each other as the artisans abandon their crafts to see the glass collector’s work. A crowd assembles. First it’s only the artisans, then the storekeepers, and then come the tourists from the boats. The glass collector steps away to join them, to view the panels from the crowd. The glass scatters the sunlight, and maybe it’s true, maybe it isn’t entirely clear what these shapes are, but it’s a breathing history, one that shouts.

The crowd draws closer, their hands running over the glass, tripping over the curves, reading the mosaics like braille. When the first piece of glass is dislodged, there’s a cry in the crowd, as if they have just discovered something. Soon, they are tearing at the panels, collecting glass in their shirts. The glass collector pushes to the front, shields the panels with his body. He tells them, I didn’t make this for you to destroy.

But when they continue, and when the glass collector stops trying to push them back, and when he tells himself he has given them what they wanted, a piece of the island, the glass collector knows that tomorrow he will pack his apartment and book a flight. Tomorrow he will call the sculptor in Chicago and tell her to clear a space for him. And if he returns to the island, it will be only to take glass from its beaches, and he will collect what he needs and then he’ll leave again.

Or:

When the glass collector joins the crowd, he sees the panels are as perfect as they could have been. How they tell the history of the island as though it is the history of the world, how the shape of his mother’s leg on the bed on which she birthed him, how the sugarcane, how the machetes, how the cruise ships. And the tourists know, and the artisan knows, and the whole plaza stays still for a long time. And he thinks the next panel he makes will be this scene now, all of them watching, all of them listening to caught breath of glass.