1.

Prayer in glossolalic language A (43 seconds):

K’olamàsiándo labok’à tohoriəmàsí làmo siándo labok’à t’ahàndoria lamo siàndo k’oləmàsí làbosiándo lakat’ándori làmo siàmbəbə k’ət’ándo lamá fià lama fiàndoriək’o labok’an doriasàndó làmo siándoriako làbo siá làmo siandó làbək’án dorià lamà fiá lama fiàndolok’oləməbəbəsí siàndó lamà fiat’andorià lamok’áyəmasi labo siàndó.

– William Samarin, “Variation and Variables in Religious Glossolalia” (1972).

2.

In a small apartment downtown, a group of people has gathered. There’s maybe a hundred of them, men and women, and they’re not exactly sure why they’ve gathered. Then, suddenly, a sound like the rushing of a violent wind comes down from the heavens and fills the whole house. Helpless, they watch as tongues of fire descend from the clouds, and then these tongues begin to move toward them, before finally coming to sit on their own tongues. The people try to speak with each other, to communicate their astonishment or terror or ecstasy, but each one is speaking in tongues, speaking in languages they’ve never spoken before or since. And then, sometime later, everyone involved is spectacularly martyred.

Or at least that’s the story I’m told as a child. The story is called “Pentecost,” and the people gathered are the apostles. At that time, I didn’t understand that the phrase tongue of fire just means a flame, so I assumed that the poor apostles watched an army of actual human tongues descend from the sky, all pink and wet and squirmy and lit up like candles, and then their own tongues caught fire. I pictured the apostles standing around slack-jawed, afraid of burning the roofs of their mouths.

I worried that one day I’d have to speak in tongues, that I’d suffer the same embarrassing fate.

My childhood anxieties weren’t entirely irrational: I grew up in a community where the phenomenon of speaking in tongues (called glossolalia by linguists) is more than just some loaves-and-fishes Sunday-school curiosity. Speaking in tongues is an everyday miracle whose practice is so commonplace that, when I’m older, the Apostles’ astonished reaction to Pentecost seems to me almost comically naive.

3.

“The literature on glossolalia is relatively scant.”

So begins Felicitas Goodman’s Speaking in Tongues, an authoritative cross-cultural analysis of the phenomenon. Dr. Goodman was primarily an anthropologist. Her research was concerned with religious phenomena and altered states of consciousness: shamanistic trances, ritual postures, exorcisms, ecstasies, and visions. From an anthropological standpoint, there’s little in Speaking in Tongues that I—an initiate into the phenomenon—haven’t already gathered from experience:

Glossolalia is often prompted by a speaker from the charismatic movement of the Christian church.

Glossolalia is often accompanied by music.

Women take more easily to glossolalia than men do.

The ability to perform glossolalia confers prestige.

The inability to perform glossolalia signals weak faith or demonic possession.

But Goodman was also a linguist, and her linguistic findings are more thought-provoking. For instance, language experts have occasionally mistaken recordings of glossolalia for a Malayo-Polynesian language. All around the world, glossolalic outbursts are of roughly equal length—like a universal bar of music—and the rhythm of these outbursts is commonly trochaic: DAH-dah DAH-dah DAH-dah. Like a stream of water or a bolt of lightning, glossolalia seeks out a path of least resistance. Accordingly, glossolalists prefer open syllables (bee, wee, goo) to closed ones (bed, wet, gob). They prefer rhymes and alliterations. They prefer the most common phonemes of their mother tongue, and avoid the least common ones. The word shunder, for example, and its variants (sunder, shuhinder, sinda, shunda, etc.) frequently appear in glossolalic outbursts, and researchers suppose that this is because shunder is a low-energy word.

4.

There’s no conversation on our drive to the church, just agonizing silence, and not even my brothers speak. We are close in age, very nearly triplets, and instinctively jocular. But I haven’t been to a church service in months, which means I’ve been regularly lying to my father. I’ve been away at college, where I maintain that I attend an ecumenical campus outreach program. I’ve researched the name of an actual pastor there, and I make up pretty sermons, which I then recite to my father over the phone. I’d been confident that this ruse has satisfied him, but now, in the car, I get the feeling that I’m a terrible liar, that he can smell my apostasy.

Our destination this Sunday is a novelty: a church on the other side of the state line, in Rhode Island, that none of us have ever attended. It’s almost impossible to imagine that such a church even exists, because I’d have sworn that my father, my brothers, and I have broken bread in every evangelical house of worship within sixty miles of our hometown in Connecticut’s Quiet Corner. It’s not uncommon for our family to attend three or even four different church services on a Sunday, the spiritual climax of a week crammed with prayer breakfasts, Bible studies, and tent revivals.

We’re not picky. We travel with ease amongst Independent Baptists and Southern Baptists and Congregationalists and Covenantalists and even King James Version hardliners, who mistrust any English translation of the Bible more recent than from the seventeenth century. But we’re not afraid of more charismatic company, so we frequent the Pentecostal outfits too: Churches of God, Assemblies of God, Calvary Chapels, Full Gospel Tabernacles. These charismatic churches are not, as their name implies, more convivial or gregarious than the other Protestant denominations, but they are certainly more flamboyant. Their members prophesize and offer miraculous healings; they speak in tongues. Some Sundays, my father seeks out stranger churches still: unaffiliated gatherings that meet in abandoned post offices and RV parks and refurbished mills. Once, only once, I remember him spiriting us into a Midnight Mass at St. Mary’s, because he wanted us to witness the spectacle of Roman Catholicism.

I’ve been raised to believe that this guileless anti-denominationalism marks my father as the truest American Protestant. He’s like an aw-shucks baseball purist who has no favorite team because, you know, he just loves the game. Along the way, he has assembled his own personal theology—comprehensive, perhaps, but hardly consistent. He is an anti-trinitarian seven-day creationist, a dispensationalist, a five-point Calvinist and a fivefold charismatic, which is a bit like saying that if he did have a favorite baseball team it would be the Yorkshire County Cricket Club. He’s opposed to female clergy members, but not homosexual ones. He’s technically a Baptist, but he cares little for the nuances of baptism. He believes that the ability to speak in tongues marks a person, that it’s a sign of God’s favor.

I get the sense that my father’s ecumenicalism, his unwillingness to take seriously divisions of creed and doctrine, is something of a scandal amongst his peers. It isn’t until college, my first real time away from home, that I begin to appreciate just how complete my father’s restlessness is.

5.

The Lord does not look at the things people look at. People look at the outward appearance, but the Lord looks at the heart.

Scripture is at least half-right: people are obsessed with outward appearances.

6.

Our destination in Rhode Island turns out to be something of a mini-megachurch, whose exterior is sleek, white, and modern—all glass and sharp angles and flying facades—and whose interior is luxe and plush. The café in the foyer sells fair-trade light-roast coffee. The sanctuary has ergonomic chairs instead of pews. Dozens of LCD flat screens beam out inspirational banalities accompanied by photographs of lambs and waterfalls, sunrises and empty tombs.

A series of tapestries hanging behind the pulpit gives the game away. In colored felt, the tapestries depict doves and oil lamps and candles. I recognize the classic iconography of a charismatic outfit, where miracles can and do happen. I wince, knowing that my project of assimilation will be that much trickier.

7.

Actual speaking in tongues, as practiced in almost 30 percent of American religious congregations, is a distinctly modern phenomenon. It begins with the story of Azusa Street. It’s a story taught to me by one of my father’s friends—a Pentecostal Cypriot named Mario—at such a young age, and with such earnestness, that it takes on a fairy-tale quality in my imagination. In 1906, a group of scandalously interracial Angelenos gathered at a run-down stable on Azusa Street and began to pray. Suddenly, the Holy Spirit came upon them, and they began to speak in what the Los Angeles Times called a “weird babel of tongues.” They kept praying like that for six straight years; thousands of people came to witness the miracle, and a cottage industry of post-factum theology arose to justify this sudden renewal of hitherto-dormant spiritual abilities.

Conservative Christians were (and still are) understandably skeptical. According to the Baptist moralist Wayne Oates:

[Glossolaliacs have] weak egos, confused identities, high levels of anxiety, unstable personality…The hyper-dependence upon alcohol, the high incidence of psychosomatic disorders, the absence of a clear-cut family structure, and the conventionalization of the church life all provide a fertile soil for the sudden chaotic breakthrough represented in glossolalia.

Weak egos? High anxiety? Confused identity? Hyper-dependence upon alcohol? Why am I such a shitty glossolaliac?

8.

I just need to survive the worship service. A simple matter of outward appearances. Each non-conforming gesture is blasphemously conspicuous. Therefore, as much as possible, conform! During prayer, for example, I never think of not closing my eyes, because I sense the dozens of righteous lookouts who keep their eyes open in order to monitor those who keep their eyes open during prayer.

Then there’s the hand thing. In a charismatic outfit, you’re expected to raise at least one hand (two is preferable) above your head for the duration of a half-hour-long soft-rock sing-along. It sounds simple enough, but the practice has never come naturally to me, so I have developed a way of tricking myself into raising my hands. There’s this game I used to play with my brothers. We’d push our arms into a doorframe and count to thirty, and then we’d take a big step forward, and as if possessed, our arms would float into the air. So with my eyes closed and with my hands at my sides, I pretend I’m pushing my arms outward into a doorframe, and after a minute or so, I pretend that—poof!—the doorframe has suddenly vanished. Up my arms shoot, without my control, and my crisis of faith will go unnoticed for another week.

9.

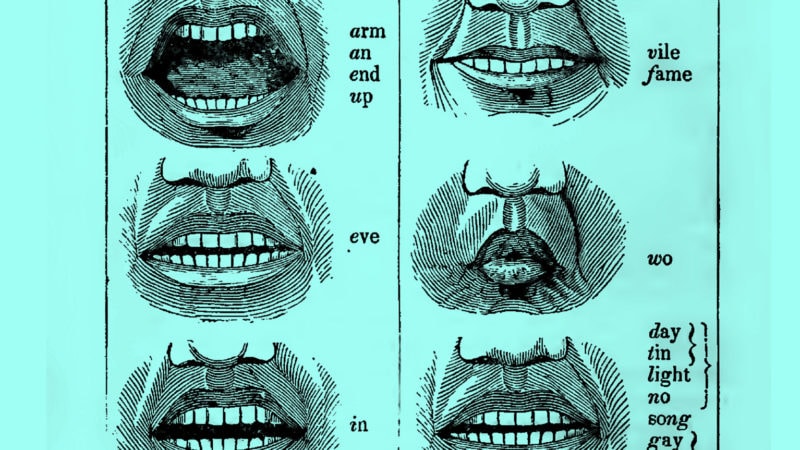

According to the linguist and phonologist Roman Jakobson, a baby’s babble is progressive. A baby starts babbling with simple phonemes, then adds more and more complex phonemes. Eventually, they exhaust all of the known phonemes associated with all of the world’s languages. But the baby’s not done. The babble keeps progressing. Soon the baby is babbling with phonemes not used in any known language, until finally reaching an “apex of babble.” Only then does the baby begin to use adult language; slowly, the complexity of the babble deteriorates, the capacity for babble itself deteriorates, and the child forgets how to even reproduce those early sounds.

10.

It’s difficult to gauge if this morning’s worship service is going to go full glossolalic. With evening services, it’s guaranteed, because an evening service is a charismatic’s nightclub: colored lights and smoke machines, loud music and casual dress. In daylight, the audience requires a bit more foreplay. The music this morning doesn’t seem to do it, or else I’ve misjudged the charisma of this congregation, because the worship remains comfortably in English.

Which, thank God, because simulating tongues is nearly impossible for me. I say simulating, but really, how can one meaningfully simulate nonsense? I’ve tried: I close my eyes, I clear my head, and…I start off my babble convincingly enough, low-energy shunder-shunda-shunder, but I can’t build momentum. It’s the same sensation as a tongue twister, like repeating the words “toy boat.” I can do it once, twice, maybe three times perfectly. But if I try to find a groove, I begin to stumble, to stutter, until finally I’m not even saying gibberish—which is unfortunate, because gibberish would be useful. I just choke on my own tongue. My babble never apexes.

Besides, it’s so much easier to mouth “watermelon-cantaloupe” for a half hour, and let others guess whether your prayer is English or angelic.

11.

There’s a guest speaker this Sunday, an itinerant preacher from Zimbabwe named Lex. Lex is a family friend, and it is for him that we made the drive to Rhode Island. A speaking gig at a mini-megachurch is a coup, so we show our support.

Lex is a giant man who dwarfs his lectern, and he knows it. He knows that his size, his blackness, and his faraway accent all arouse his audience’s attention. As an orator, he uses this arousal to his advantage. After Lex is introduced, he approaches the lectern, but he doesn’t immediately speak. Like a strongman readying himself for a carnival high-striker, he removes his blazer, revealing a pinstripe shirt with a mandarin collar stretched tight to the point of bursting. Still he doesn’t speak, but methodically folds the blazer and sets it aside, rolls up his shirt sleeves to his elbows. Somehow, his forehead is already dripping with sweat. Eventually, his lips, his beard, and even his ears will be dripping; his eyes bulge, but he still won’t speak. He glares at the congregation. He sweats some more. Altogether, this scene gives the effect of some momentous labor that has already taken place, the fruits of which Lex will share with us in his own time.

12.

According to Michel de Certeau, glossolalia “is a trompe-l’oreille, just like a trompe-l’oeil…It speaks for the sake of speaking, so as not to be tricked by words, to slip the snares of meaning.” Even more than trompe-l’oeil, the phenomenon of glossolalia reminds me of the pseudo-Kufic in certain paintings of the Early Renaissance: ornate tangles of gilt calligraphy meant to signal Arabic or Hebrew or Aramaic, written by artists entirely ignorant of the actual orthography of those languages. Not glossolalia, exactly; more like glyphtolalia. Writing for the sake of writing.

Now, these artists must have known that the pseudo-Kufic which decorates a halo of the Virgin Mary is complete gibberish, but suppose you were to ask them, “The Mary of the painting, can she read your inscriptions?” Or, “If you artists were transported into the painting, could you read your inscriptions?” How might they respond? How far down does the gibberish persist?

And God Himself, is he able to understand the glossolaliac? Can God transmute sense from nonsense? Or is it just gibberish to him as well?

13.

It’s said of Lex that “the boy can preach,” and this Sunday’s sermon is typical of his style. When Lex finally speaks, it is to firmly establish his theme, which today, comes from Isaiah:

To whom has the arm of the Lord been revealed?

He reads it again.

To whom has the arm of the Lord been revealed?

The verse becomes something of a mantra that Lex will repeat no matter how far astray his sermonizing might otherwise carry him. He’ll go down some real rabbit-trails, speculating on the Christological identity of King Melchizedek, on quantum cosmology, on the history of New England revivalism. But, always, he returns:

To whom has the arm of the Lord been revealed?

He will shout and whisper and sing these words. Sometimes he’ll simply sigh into his lapel mic, so abruptly that it makes me jump, and then he’ll bare his teeth and grimace at the crowd, eyes bulging. It’s a grimace that Chrysostom would have called ἐμβλέψας, the same look used by Christ when he confounds his audience, when his words or actions make too deep an effect…and suddenly, it’s twelve o’clock, universal closing time. I feel a sense of relief and of accomplishment. My duty has been fulfilled. Soon we will be back in the minivan, driving in silence towards Connecticut.

14.

“Phrases such as ‘falling down’ or ‘slain of the Spirit’ are based on the physiological/psychical experience of the initial onrush of glossolalia.

Once the experience has transpired, the person feels ‘wonderful.’”

-Clint Tibbs, Religious Experience of the Pneuma (2007).

15.

But the service takes a turn I didn’t anticipate. Lex begins to pray, as if he has finished preaching, but it’s already past twelve, so the service should be over. And yet, Lex’s prayer is more earnest than mere benediction. He keeps generating sweat, and his voice grows louder, until he’s not even praying really, not in a formal sense, just repeating the verse from Isaiah so forcefully that it sounds like a challenge or a threat:

—To whom has the arm of the Lord been revealed?

My eyes are clenched shut, so I cannot see whether the music arrives spontaneously, or if Lex has given some signal to the band, or maybe this whole finale was planned in advance, but in any case, there’s music now, always the music, which isn’t a good sign at all. Just arpeggios from an amplified keyboard and the menacing glissando of bar chimes, which should sound harmless, but I know from experience how it’s done. I remember all of the times, growing up, that Lex had called upon my services as a keyboard player, had signaled for me to slip away from my seat and join him on the stage. He’d taught me to play the arpeggios softly, the simplest possible chord progression—C-Am-F-G—so simple that even I, sheet-music-illiterate, can titillate a congregation towards glossolalic climax, just as the band does now. The music builds, and instead of heading to the exits, the entire mini-megachurch quits their ergonomic seats and presses in towards the stage.

—To whom has the arm of the Lord been revealed?

The whole assembly erupts with tongue babble. Women are openly weeping, and men are shouting, trying to out-shunder their neighbors. My own tongue is quickly tied in a knot—too many high-energy words—so I try to “watermelon-cantaloupe” my way to anonymity, but I open my eyes, and to my horror, I see that Lex, the giant, is actually getting down from the stage. He’s like a fierce king descending from his dais. He’s soaked with sweat, and the chime bar tolls, and then he’s amongst the blathering throng, and he’s actually slaying people in the Spirit, knocking them dead with a touch of his hand, shouting his mantra while ushers drag away the corpses. It’s a miracle I’ve heard of, of course, but have never seen up close. I didn’t even know Lex was capable of producing this effect. I’m almost proud of him, when it occurs to me that this is a development for which I’m completely unprepared. How does one fake being slain? Worse, what if I actually am slain?

16.

I am afraid of glossolalia, it’s true. And in moments like the one with Lex, I’m more than a little embarrassed by my own inaptitude. But more than fear or shame, I feel envy for the glossolalist.

Glossolalia is extravagant. It is excessive and conspicuous. I used to think how liberating it must be to burst free from the constraints of everyday language, to escape into an ecstasy of nonsense. Looking back, I understand that escapism isn’t enough to explain a phenomenon like glossolalia. After all, Ella Fitzgerald’s scatting, county fair hog-calling, Dadaist cut-up poetry—all these escape the strictures of everyday language. Escape is easy.

The speaker of tongues isn’t escaping into some prelapsarian stage of ignorance. They aren’t regressing; they are congressing. My brothers, my father, Lex, and these hundreds of total strangers are together forming a community whose ties are as impenetrable to me as they are absurd. And I, with my hand-games and my watermelons, am not included. Tongues really do mark a person. They signal an unsparing willingness to be counted as a member of a tribe, and their practice is like a shibboleth, a sieve through which I feel myself slipping.

17.

My brothers have abandoned me. They’ve fled towards the altar with everyone else, pressing their way through the crowd in order to receive the arm of the Lord. Lex grabs hold of one of my brothers, and I watch as he seizes and falls. I still have no strategy for any of this, so I continue mouthing “watermelon-cantaloupe,” but I’m also praying—actually praying—that I survive this rampage. But Lex is coming straight for me, slaying a path to me through the thick crowd, mowing down everyone between us, his huge hands like holy machetes. From the corner of my eye, I watch the body of my second brother being carried off by a pair of ushers to be resuscitated, until finally it’s just Lex and me, and my tongue catches his spittle as he cries out

—To whom has the arm of the Lord been revealed?

and seizes me by the wrist, and I swear I feel something, a supernatural electrocution, but it’s just my own surprise. I don’t faint at all, no matter how forcefully Lex yells, and it’s almost embarrassing how long he lingers there, squeezing my wrist, trying his damnedest to slay me, until, like a thwarted lion, he gives me up and seeks out more willing prey, leaving me standing by myself chanting “watermelon-cantaloupe,” while my father looks on in confusion at his unslain son, my brothers still in a stupor, watching me like some unholy thing, and I wonder what I should have done differently.