One day during the last school year, as the first leaves fell, my first grader’s school folder came home with a letter to parents. It’s a blue folder like every other first grader’s, with a fat white C.H.E.F. (Communication Home to Every Family!) label affixed to it. The first graders are “cookies” this year. Last year they were “bees,” of the “busy” variety, as if there is any other kind.

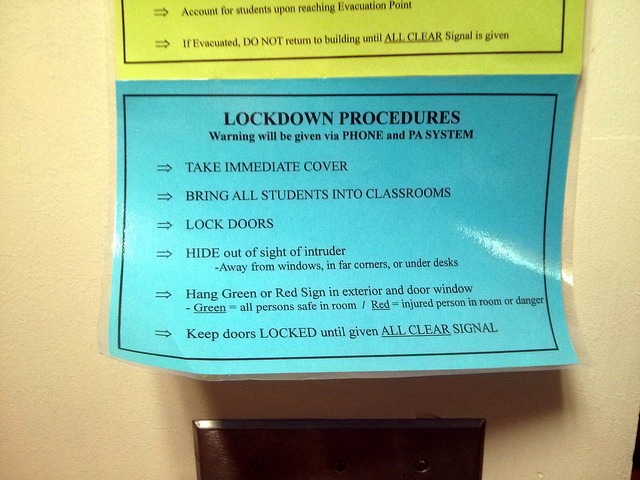

Dear Parents, it began. We wanted to make you aware that on Wednesday, just as we practice fire drills, teachers will be conducting a mock “hard lockdown” in their classrooms. Classroom doors will be locked and the children will be asked to sit quietly in a safe part of the room.

My mind sprang immediately to the children at Sandy Hook Elementary School. My daughter was in kindergarten when those murders occurred. If we happened to live in that part of Connecticut instead of Brooklyn, she might have been gunned down with her fellow classmates and teachers by a mentally ill young man with numerous assault weapons. The idea of those children conjures in me a sickening sadness that has no fathom. There is no rational way to consider so many small children, their terror, their pain, their blood, without a wave of nausea followed by a vicious snap of fear, a pitbull at my throat.

Obama stood up and declared that he would change things. He tried, but failed.

What, then, is an appropriate response to such a note, in the wave of such events across our country? Should I be glad they told me, or should I wish they hadn’t? Is a citizen’s response the same as a parent’s response? I cannot understand resistance to laws that require background checks for gun purchases, or ban assault weapons. Or both. In the months of outrage that followed Sandy Hook, parents stood up and wept at podiums. Photos of smiling kindergarteners, shot dead in their classroom by a deranged young man with his parents’ guns—were everywhere. And then they weren’t. Obama stood up and declared that he would change things. He tried, but failed. Congress did not act.

In the year since, he has stood up so many times that, finally, just this week, as another troubled young man in Roseburg, Oregon went to his college campus armed for combat, bullets flying, and murdered another nine innocent people, the President could only point out, exhaustion stretching his face, that mass shootings are partly a result of “[A] political choice that we make to allow this to happen every few months in America.”

The idea that the purchase and use of guns ought to have some oversight isn’t new: Regulations on who could pack a pistol, and under what circumstances, go back over two hundred years. The first contemporary legislation to limit or restrict what people could do with guns came in the 1930s, between the wars but in the wake of now-infamous sprees by Al Capone, John Dillinger, and Bonnie and Clyde. The fact that history has glamorized them, and other outlaws, with endless Hollywood and re-enacted docu-drama, is a good indication of how little we consider their victims.

Even though the number of people who die from gun violence in America is twenty times the average of other developed countries—that’s close to 12,000 people murdered every year—over the past twenty years our ability to effectively manage who is allowed to own what type of gun—has drastically declined.

How did this happen? The march to modern massacre began in 1986, with the Firearm Owners Protection Act, legislation that gutted the ability of the Department of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms to do its job. Specifically, it prohibited the creation of a National Firearm Registry. While assault weapons were banned and background checks became mandatory after James Brady took a bullet for Ronald Reagan, the previous legislation prevented holding on to any record of who bought a gun. By the 21st century, assault weapons were back in action. Under the first Bush administration, gun manufacturers were granted immunity from civil lawsuits over gun-related violence

Before the practice drill, teachers will be having a sensitive conversation with their students about the importance of a practice lockdown drill. They will explain that just as it is important to practice fire drills, it is also very important to make sure that we are safe if there is ever a stranger in the building. Some students may have heard about the drill already and we wanted to make you aware, in the event that you wanted to have a discussion with them at home.

This was on me; my husband was going out that night and wouldn’t be home before bedtime. I texted him.

“What should I tell her?” I asked.

“Tell her it’s to protect her if there’s a bad guy in school. She can relate to the idea of running away and hiding from bad guys,” he said.

I said okay, and later that night, before bedtime, I brought it up as casually as I could.

“So you have a drill tomorrow, like a fire drill. So that you know what to do in case there’s someone in the school who isn’t supposed to be there. Like, a bad guy.”

She was nonchalant, even dismissive, in the way only a six-year-old can be. Imitating an attitude she can’t fully inhabit yet.

“I know about it already, mom.”

She was nonplussed. I let it go.

But I thought about it all day, and the next night, I asked, in as offhand a way as I could muster, while returning an army of mismatched socks to her drawer, “So what was it like? The lockdown thing?”

She shrugged. “It was nothing,” she said. “We, like, sat in the corner. Our classroom doesn’t even have anywhere to hide.”

My heart dropped. As in, free fell, like a box of gold, a cannonball, as if all my organs had been vaporized. The weight of my fear was staggering. No place to hide. I had to sit down. I had to say something. What should I say? No place to hide.

While the vast majority of Americans support background checks, and over three million have joined the anti-gun violence group Everytown for Gun Safety, our lawmakers seem intent on making sure that buying a gun is A-OK for everyone. Commensurate with that decision, parents get to fear for our children’s lives at school every day, not to mention numerous other formerly innocuous-seeming places that children go: the playground, the mall, even at the damn movie theater. Granted, parents fearing for the lives of their children is nothing new. Across the globe, across the millennia, children have died. Stillbirth, war, famine, enslavement, disease: there has always been much to fear on behalf of the most vulnerable members of our society, and the ones we most cherish and are biologically programmed to nurture and protect.

Fear that something bad will happen to your child (or loved one) is much more potent than fear that something will happen to you because that’s how humans are wired; altruistic fear trumps personal fear when it comes to violence of every kind. Which is exactly the point: it’s the kind of violence I fear that is different than it used to be. Or so it seems.

Though I’m not unafraid of these things, they seem more farfetched than the idea of someone marching into my kids’ school with an assault weapon and a grudge. It is the plague of gun violence that has made its insidious way into our lives and the lives of our children in a way that will be seared into their minds forever.

Even so, if we assess the traditional risks to children, today’s picture does brighten. In colonial times, a third of children died before age ten; by the turn of the twentieth century, one in every five died before their fifth birthday. According to the CDC, only 26.3 out of every 100,000 U.S. children dies before age four today. Halve that number for 5-14 year olds. That is a significant improvement. Great!

What are those kids dying from? Guess. According to the Children’s Defense Fund, in the past thirty years, 112,375 infants, children, and teens were killed by firearms. Consider that number this way: More children died from gunshot wounds than soldiers killed in Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan combined. It’s not even surprising, since there are 310 million civilian guns floating around, which works out to about one for every citizen. Armed forces and law enforcement officials, combined, only have four million. Kids from poorer neighborhoods are vastly more likely to be injured or killed by a gun than their wealthier counterparts.

So many shootings. A mantra, a prayer, a dirge for our times: Columbine, Aurora, Newtown, Roseburg. Again and again, the same grim faces on law enforcement officials at podiums, the same stunned faces, hands clapped to mouths, blanket our screens. Which brings me back to fear, and whether my fear is well-founded or needlessly hysterical. Certainly, fear for one’s children is a common denominator across all cultural lines, in all scenarios: famine, war, gangs, disease. And fear for another person’s well being—altruistic fear—is more potent, more consuming than personal fear. It “may be considered more of a problem than personal fear.”

Reminding myself that I can’t walk around being scared all the time doesn’t help me let go of the sense that my child—all of our children, to varying degrees—are, actually, truly, daily, in danger, and that they are in more danger now than I was as a child, and I was born in New York City, and raised here, in Queens, in 1970, at the start of one of (arguably) the most dangerous decades in the city in a hundred years. My mother feared a multitude of things both mundane and profound: That someone would steal her name from a magazine label (she scraped them off); that there wouldn’t be enough food for dinner if my little friend stayed late; that we would be carjacked if we left our windows rolled down while we drove through our neighborhood; that we would get pneumonia if we went out without a hat. My brother and I were whisked to the doctor at the first sneeze or cough; our home was devoid of wool, down, dander, and anything else that could potentially cause anaphylactic shock, despite the fact that no one in my house was allergic to these things.

I wonder, then, if my sense of dread is on some level innate. While my mother’s fears could be associated with a mild anxiety disorder—and I’m not saying they aren’t—the truth is that I come from a long line of people who undoubtedly ran from men with lit torches and the sound of shattering glass and burning barns, marauding citizens and marching soldiers. If epigenetic changes caused by trauma such as the Holocaust, or enslavement, can be passed through generations, as researchers have recently found, perhaps some of us are hard-wired to be afraid because our history has taught us that fear is a kind of armor.

Yet in my life before children, I was rarely afraid. My neighborhood was not the best, or the worst, of its era in New York, but it was mine, for better or worse, and though I thought twice before walking down certain streets after dark, I never heard a shot fired or knew anyone who was shot to death. When I was a kid, the news did not carry stories of children shot in school by friend or stranger. I was unaware of mass shootings. The only drills we ever had were fire drills.

This is one of two mandatory lockdown drills we will have this year.

Right after the Newtown shooting I instructed my clever, quick-footed daughter that if she ever sees or hears anything frightening at school—people running away screaming, loud booming noises, anything like that—she is to run and hide immediately. She is not to wait for any friends, or to be instructed by an adult. She is to run as fast as she can away from the perceived danger to the safest and most silent place she knows that is nearby. There wasn’t a lot of discussion around it. She doesn’t watch television news, and was not exposed to the twenty-four hour cycle of images: the grinning school portraits of gap-toothed kindergarteners who had been killed; terrified parents clinging to surviving children; black-clad SWAT teams; aerial views of emergency vehicles; and the ubiquitous photograph of the accused, a vacant-eyed, smooth-cheeked, young man with a history of mental illness who happened to live in a house where there were lots of guns.

Am I suffering from a kind of PTSD, then? Is my fear irrational, an outgrowth of the sort of overprotective parental culture bemoaned by Hanna Rosin in The Atlantic, cognitive bias borne of excessive media coverage? An overreaction along the lines of the school district in Maryland that suspended two six-year-olds last year for pretending that their fingers were guns? (Finger-guns, yes. They were playing cops and robbers.) The BBC found 130 separate “lockdown” incidents at American schools and campuses last year in a single month long period.

While lockdowns on this scale and the sudden familiarity with phrases like “shelter in place,” may be new, shots fired at school are, it turns out, old news. This has been going on pretty much since the beginning of the American love affair with guns, which is to say, the beginning of the United States itself. There are dozens upon dozens of historical incidents in which kids brought guns to school and shot somebody, either on purpose or by accident. In November of 1853, for instance, Louisville student Matthew Ward bought a pistol one morning, went to school with it, and killed his teacher “as revenge for what Ward thought was excessive punishment of his brother the day before.” He was acquitted.

A few years later, also in Kentucky, a colonel’s son was shot to death in the schoolhouse by a boy he’d been bullying. The Los Angeles Herald warned after an 1874 school shooting of “the too common habit among boys of carrying deadly weapons” and recommended pocket searches by teachers. “The hills west of town are not safe for pedestrians after school hours,” the paper cautioned. The list goes on and on, into our own century. Teachers shot by angry students; girlfriends shot by rejected suitors; bullies shot by their victims.

The fact that this has happened throughout history isn’t reassuring; if anything, it’s an even stronger argument for the necessity of common sense regulation. “Stuff” may “happen,” as one of our estimable presidential hopefuls recently pointed out, but in the times we live in, it happens with alarming frequency, and with weaponry of the sort that can mow down dozens of human lives, whatever their stature, in an instant. In addition, these times make the perpetrators instant celebrities, their faces beamed across hemispheres into infamy. Be they vilified or esteemed (by similarly disaffected, disenfranchised, or disturbed individuals), the shooters are forever known, which seems, in some cases, to trump the fact that they are also, for the most part, dead.

In light of this long history, I’ve tried to uncover the actual probability that my daughter might be actually be massacred at school, and come up with a range of numbers, from a reassuring steady two-to-five a year since 2000 (published by Slate as a line chart that appears artisanally crafted to make people dizzy); to CNN’s breakdown (fifteen shootings inside a school in the eighteen months following Newtown); to Everytown For Gun Safety’s shock-inducing stats on the same exact period (they counted ninety-two).

The problem is that whatever the statistics tell me, and however much I know about the history of this phenomenon, my fear remains.

Various statistical breakdowns have told me that my child has a .002 percent chance of being shot at school for every 100,000 hours spent at school; a 1 in 141,463 chance of being shot at school (this in 2012 from psychologist Dr. Max Wachtel); and an even more reassuring “seven deaths for every 10 million children, or a 0.00007% chance for any one child.” According to that last source, the dubiously named Irregular Times, an asteroid colliding with earth is a more likely scenario.

The problem is that whatever the statistics tell me, and however much I know about the history of this phenomenon, my fear remains. This is because it comes not from lack of information, but lack of control, which is perhaps the root of all fear.

What am I to do about this inability to protect my child? If enough voices rise up, I want to think, our officials must listen. If we cease to elect people who refuse to pass gun legislation, they will listen. If gun owners, be they sane enthusiasts, or hunters, or people who sleep atop mountains of diamonds, would offer support for legislation that won’t in any way restrict their use of guns, but protect, say, a bunch of kindergarteners—maybe we can gain some control. If we—or maybe just I—remind myself daily that a mass shooting at my child’s school is unlikely. Not impossible. But improbable.

Bill Bond, the school safety specialist for the National Association of Secondary School Principals was quoted by CNN shortly after Sandy Hook. Here’s what he had to say: “There is not a single safety measure that anyone could have put in place at that school that would have stopped what happened…When you allow absolutely insane people to arm themselves like they’re going to war, they go to war.”

I stare at my little girl, fast becoming a big girl, in the low light of her before-bed story time.

“What do you mean, there’s no place to hide in your classroom?”

She rolls her eyes. “There’s just not,” she says. “My teacher said we could just sit on the floor.”

I scan through my memory of her classroom. It’s pretty tight in there. Twenty-six kids. Teacher doesn’t have a big desk made of metal like my teachers used to. Nothing that could barricade the door. I feel my heart beating in my chest, and reach out to stroke her cheek. I hope that I’m not radiating fear. I don’t want her to be afraid. Really, I don’t.

“There’s the closet where she puts your coats,” I say.

“Oh. Yeah,” she ventures, unsure of what I mean. Our eyes meet.

“Well if something happens, baby, and you’re scared, you get in that closet. You get in there and you close the door and you do not come out unless you know it’s safe.”

She holds my gaze, not scared, not amused, just considering. A rare moment of stillness, for her.

“How will I know it’s safe?” she finally asks.

I try to keep my face steady.

“You’ll know,” I say. And hope that it is true.