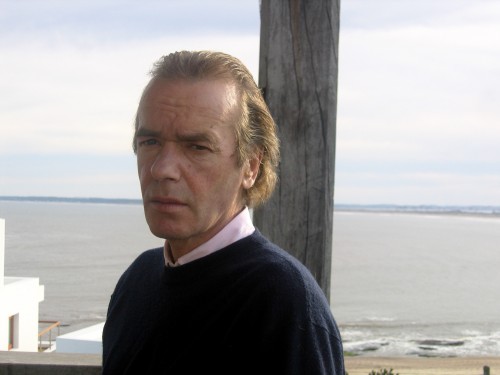

Late one Saturday morning last November, Martin Amis strode across the stage of a half-filled auditorium at the Miami Book Fair. Squinting as the light struck his face, Amis took a seat at a lonely table with a copy of his most recent work, Lionel Asbo: State of England.

Stern-faced, he commended the audience after a brief greeting. “You avoided electing a president who looks like a religious porn star, one much respected in the industry,” he said. “You avoided the presidency of a man who a few months ago sat in Jerusalem next to Sheldon Adelson,” he continued. “You’d have to rack your brains to find someone, anyone as disreputable as that. Perhaps if he’d had Larry Flint sitting on the other side of him…” The official schedule described the event as a reading, but Amis, often referred to as the Mick Jagger of literature by the British press (“Why isn’t Mick Jagger known as the Martin Amis of the rock world?” he’s joked), chose to start with a short speech on American politics and religion. “[Romney] is a hick,” he said alluding to Romney’s Mormonism, a religion, which, in his opinion, didn’t deserve discussion, given its short and somewhat ridiculous inception.

“I was just amazed that the election was so close,” he continued. “The Democratic Party represents the American brain, and the Republicans represent not the American heart, or soul, but the American gut. The argument between brain and bowel, everywhere else in the Free World, has been decided long ago in favor of brain. But Americans still—it still divides the nation, this question, here in America.”

Amis is well versed in provocation, but he hasn’t always shown a significant interest in politics. Early in his career he was largely seen as a literary playboy, avoiding the political scuffles that his late friend and colleague Christopher Hitchens ardently pursued. In recent years, however, Amis has taken on a wide range of culturally sensitive subjects, including communism, the press, and Islam. Throughout numerous interviews, he has managed to anger both the Left and the Right with caustic statements that altogether dispense with political correctness. His 2011 move to Brooklyn seems only to have heightened his effervescent rancor.

With Obama’s second term underway, and Amis’s mind focused on the new novel he’s been working on about the Holocaust, our conversation revolved around his recent travels and research—never veering far from the contrarian repartee for which he is known.

—Santiago Wills for Guernica

The New York Post is The Atlantic Monthly compared to tabloids there—the indulgence in vulgarity, the wallowing in vulgarity.

Guernica: You recently described the events surrounding your main character in Lionel Asbo as particularly English: “And the egotism of people who are eminent without being in the least distinguished and somehow feeling that’s their due—that seems to me to be a peculiarly English phenomenon.”

Martin Amis: That exists everywhere, but it has a different flavor in England, where the tabloid culture goes much deeper than here. In fact, there’s no equivalent to the three or four major tabloids in England. There, it’s all like The National Enquirer. The New York Post is like The Atlantic Monthly compared to tabloids there—so it’s just the indulgence of vulgarity, the wallowing in vulgarity. As with everything English, there’s a sort of irony to it. They write a great deal about these trivial people who have a certain eminence, always with a bit of, “Isn’t it ridiculous that we are writing about this person?”

But it didn’t strike me until quite recently, certainly after I had already finished the book, that we have a huge institution that celebrates the undistinguished, [an institution] which is nearly as old as the Papists. It’s been going on for millennia. What else is a monarchy but a series of ridiculously exalted figures who are not necessarily distinguished at all? In fact, they have a rather philistine tradition. So perhaps we are more vulnerable to it than other countries.

Guernica: In a way, Lionel’s desire to change himself through the press resembles some of Latin America’s kingpins, specifically those seeking to become part of a social class that was always obstructing their entrance.

Martin Amis: I do think some of them feel that way, but I don’t think Lionel does. He’s rather set against self-improvement. It’s almost a point of pride with him that he’s not going to do it, and I think that’s a very endearing thing.

My father once said there’s a correlation between a nation’s cuisine and its people: England, nice people, nasty food; France, nice food, nasty people; Spain, nice people, nasty food; Italy, nice people, nice food; and Germany, nasty food, nasty people.

Guernica: You’ve said that you admire incorrigibility, and stupidity as well. Many writers have shared similar concerns. There’s Flaubert with Bouvard and Pécuchet and the Dictionary of Received Ideas, and Ambrose Bierce with The Devil’s Dictionary.

Martin Amis: Yes, I think writers are excited by stupidity and bad behavior, generally. And it’s a certain kind of chore, a perverse kind of mission fulfillment in that these violent characters do all the things you would never do. There’s a certain sort of kick about writing about all those things. It’s sinister, and it’s so gratifying in a weird way.

But that’s what novels are. As someone once said, covers to a novel are like bars to a cage. You can watch the tiger, the Komodo dragon, and admire it—its heart, its severity. Even when they carry out an ugly act, it’s still fascinating.

Guernica: You lived in Latin America for nearly three years. What was particular about the Latin American mindset compared to North America and the UK?

Martin Amis: I can only speak for Uruguay, really, and they must be the nicest people there. I think Borges said that when Argentineans die they turn into angels and go and live in Uruguay. But for the rest of South America, you have to say that it’s getting there—becoming civilized—and will get there. It’s had a real grit war in history. The choice between those societies until recently was the choice between tyranny and chaos. Everyone understood that. You’ve got to have a strong man, or it’s going to be a mess. There’s Chile and there’s Uruguay, and no one quite knows why Uruguay is so appealingly selfless because they’ve had their terror and their revolution like all the rest. But somehow, there’s something in them.

One thing you can’t help noticing in South America and in Latin culture, generally, is how nice people are. Although when I went back to Spain (my mother lived in Spain and both my brothers lived there) after the Uruguay trip, I thought, “Oh great, Hispanic people.” But they weren’t nearly as nice as the Uruguayans. They’re quite proud and pissed off, the Spaniards. The Uruguayans have a sort of purity. I don’t know where they got it, and I doubt even if they know from where they got it. Perhaps they didn’t kill off their major population. I’ve always said that the big difference between South America and North America with regard to the native population is that in North America they raped them and killed them, and in South America they raped them and married them. The mix was much greater, and that was very good.

When I read French non-novelists, people like Bernard-Henri Lévy, philosophers—they never say anything. It’s all sort of flim-flam. I accept that if I were a French intellectual I wouldn’t say anything either because there’s nothing to say.

Guernica: In 2009, you returned to Colombia for the Hay Festival in Cartagena. Six years before, you had traveled to the slums of Cali to report on crippled murderers. Was the contrast shocking?

Martin Amis: Yeah, and an interesting thing happened, actually, in Cartagena. I talked onstage about my experiences in Cali and there was a sort of “Hmm,” a sort of mewling. They didn’t like it. They even sort of suggested that it wasn’t true, or that it ceased to be true. So in Cartagena it’s hard to believe it’s in the same country as Cali because it’s so beautiful and so civilized, and there is such enthusiasm for good things—writing, music, novels. It was a good thing to come across that denial, that reaction, because I was able to compare it, oddly enough, with Germany, where I was earlier this year.

The book I’m writing at the moment is my second book about the Holocaust, so when I was there I said to the girl who was taking me around, “I suppose they don’t know here about that.” And she said, “Oh that’s not true.” My respect for the Germans went up. My father once said there’s a correlation between a nation’s cuisine and its people: England, nice people, nasty food; France, nice food, nasty people; Spain, nice people, nasty food; Italy, nice people, nice food; and Germany, nasty food, nasty people [laughter]. And I’ve always thought that there must be something terribly wrong with the German character—and that there is, really. It’s a young country (1871) and a German only feels comfortable being with the masses. They have very little talent at creating an inner life, privacy. And I think there must be something wrong.

Anyway, in Germany, they were very interested in talking about their past. I respect that, and I think they’ve done quite well. It’s become a kind of obsession, as it bloody well should, when compared, for example, to France, which hasn’t done anything. France has done no work about their part in transporting eighty thousand people to their deaths. They are still the guy in the leather jacket with the onion, who’s a part of La Résistance. In fact, they collaborated, not resisted. I said once that when I read French non-novelists, people like Bernard-Henri Lévy, philosophers—they never say anything. It’s not actually anything you can extract from that person. It’s all sort of flim-flam. I accept that if I were a French intellectual I wouldn’t say anything either because there’s nothing to say. That is, unless you do the work. They haven’t begun to do the work, and I think that’s fucked them up.

Guernica: Why do you think they haven’t done that work in France?

Martin Amis: They just won’t admit it. First, you get your army beaten in three weeks. That’s not great for your pride. Then you enthusiastically collaborate. French police did the round up. It’s just very shameful, but you’ve got to face it. You have to talk about it. That certain snobbery of certainly the Parisian—combined with a complete denial of your historical legacy, is just awful. That’s a funny thing about France. Saul Bellow wrote somewhere that he saw right through the French. He lived there. He wrote The Adventures of Augie March in Paris, and there’s no one better than him to say what’s unbearable about the French. But, he says, funny enough, what they think of your work is tremendously important. And it is. It’s more than what the Italians, the Spanish, and the Germans think. Somehow it’s still got that cultural primacy. I feel that too: to get praised in France is better than to get praised anywhere else.

Guernica: In May 2009, in an interview with Prospect magazine, you discussed your enthusiasm for the possibilities of the Obama presidency. What are your thoughts on his first term and on what might come in the next four years?

Martin Amis: It’s often said of American politics that it’s a huge juggernaut and the president can change the direction by two or three degrees in either direction, but not much more. In fact, I think the president’s power is limited, much more than the prime minister in England. So, I’m not too disappointed, although I didn’t like his deportations, and I’m not sure about the drones. It’s very aggressive. I’m not sure that if Bush Jr. were doing it I would say the same. It’s better than having troops on the ground, and it’s horrifying for the terrorists. I mean they’re all sitting there waiting.

I haven’t liked him during the campaign. He hasn’t been above the fray. I guess you can’t afford to do it. If you are going to get reelected you have to make some of the usual noises: You don’t talk about global warming, and you don’t talk about gun control. He hasn’t been the great exception.

I also think there’s been another resurgence of racism. All that rejection from Republicans has a bit of a racist element. It was very necessary to have a black president, and it’s been a great thing. It will help, in the end, to ease the trauma of slavery and civil war. The war against slavery cost almost 800,000 American lives—that’s how strongly they felt about it. And it’s not going to go away in a century.

Obama will have a bit of capital for a year or two. Even his imperfect health reform was a tremendous step in the right direction—the direction of sanity and equity. Just to give up this enterprise health system and adopt government health care like in Canada is cheaper and fairer. But the key part about that is that no American will accept that some of his tax money is going to pay for people who smoke. It’s horrible for them: “Some low-life bum taking advantage of the state.” They just have to get over it.

Guernica: In his recently published memoir, Salman Rushdie describes the general feeling of the 48th Congress of International PEN in New York in 1986. Rushdie says that back then, as opposed to today, writers could still claim to be, as Shelley said, the “unacknowledged legislators of the world.” Do you think Rushdie is right?

Martin Amis: I think it’s likely that the civilizing effect of literature has done most of the work, and still continues to do. Look at Steven Pinker’s book, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. It proves beyond any shadow of doubt that violence has declined dramatically throughout the centuries. There are various reasons for it: the rise of the state, Leviathan, the monopoly of violence, children’s rights, animal rights. They’re all positive signs. But, he says, the one he puts his money on is the invention of printing, and, funny enough, the widespread appearance of fiction. He says this taught empathy (he doesn’t like the word, but he says there is no better one). If you read a novel, you’re in someone else’s head, in three, five different people’s heads. Suddenly, the principle of “Don’t do anything to anyone that you wouldn’t want done to you” becomes real in people’s minds. That’s a fantastic achievement if fiction is indeed partly responsible for it. That’s a great thing to be a part of. In the end, then, I don’t know if writers have legislated, but they have civilized.

To contact Guernica or Martin Amis, please write here.