Vyacheslav accidentally slammed the door of the shuttle bus and the driver yelled at him. “Oh, big man, eh? Tough guy, huh? Take it easy on the fucking door next time, tough guy!”

Vyacheslav didn’t need this shit, but he wasn’t in the mood to argue. It was hot in the shuttle bus and he sweat. He watched out the window as they passed the national cemetery for the Siege dead. He didn’t want to look at that and turned his head the other way. On that side, it was green and idyllic. But Rafik’s grandmother had told them that the bodies are buried there too, where Vyacheslav used to run and play as a kid. Well, what difference did it make if you were buried in a cemetery where people were somber and prayed or under a beautiful park where future generations of little boys trampled over your unmarked bones in their sneakers? It didn’t make any difference.

He took the three-day notice out of his pocket and looked at it. It was dated three days ago, and everything had failed this time. They’d turned down his conscientious objector petition because they turned down all conscientious objector petitions. He couldn’t afford to pay off the doctors to buy an X-ray showing a crack in his spine. And he’d been kicked out of the university, which was no surprise really. It was his own fault that he chose drinking all night with the ship captains on the Griboyedov dock to going to class. So who could even be bothered to feel sorry for him? Maybe only his mother, who was home right then cooking his last meal, his favorite, pasta with chicken hearts, a meal he’d eat cold in the morning before going to the military enlistment office.

The past three days he had sat at home completely resigned. He watched cop shows on TV and played City Gangs on VKontakte. He was out of options. He’d chosen to spend his last night of freedom at the Panda pool hall with Rafik.

Rafik was waiting outside the Panda smoking. He wore turquoise shorts with a tropical print and a pink button-up shirt. Only Rafik could pull off a getup like that. Slung over his shoulder was a black tube with his cue in it.

“Brother,” he said. “It’s good to see you.”

Their embrace made Vyacheslav swallow hard. He had not cried since his grandfather died, and he did not plan on crying now.

“Let’s play,” Vyacheslav said. “I don’t want to talk about anything. Let’s just play.”

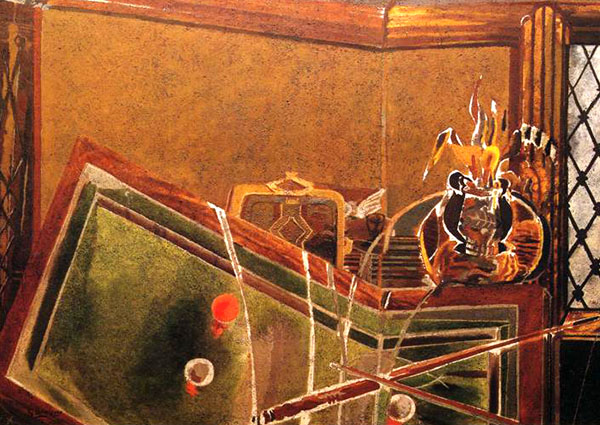

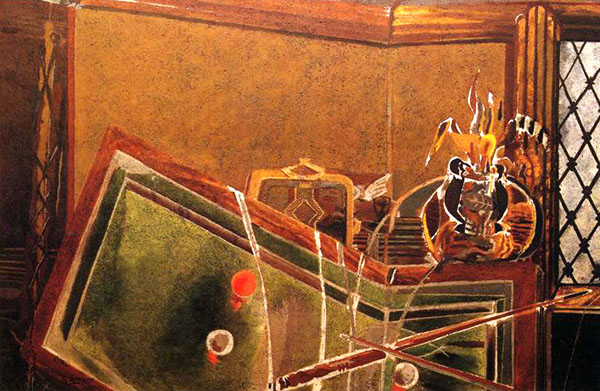

They went upstairs. The darkness was thick in the Panda and punctuated only by the bright lights over the pool tables. It made the room shadowy and shifting, which comforted Vyacheslav. Some stupid music played.

A game in which you used a claw to grab cheap stuffed animals stood at the top of the stairs. The cleaning lady stood in a room of slot machines off to the right. She seemed to be asleep, propped against her mop, which was a wooden pole screwed into a two-by-four with a rag wrapped around it. At the bar stood Vera, Vyacheslav’s ex, shaking her head and smiling.

He blew her a kiss and thumped his neck playfully.

Out of gratitude he had taken her by bus to Helsinki for the weekend before breaking up with her.

Vera had kept Vyacheslav from going to the army the last time. She had made him cribs for all his exams. Thanks to her, he presented as a star student of the military and space academy. Out of gratitude he had taken her by bus to Helsinki for the weekend before breaking up with her. Sometimes they still spent the night together.

“Give us 500 grams of Standart, Verochka,” Rafik said. “And we’ll take that table there.”

“That’s my table, pinkie,” a man at the end of the bar said.

“Take it easy, pops. You’ll get your turn.” The man was one of the beggars from Nevsky Prospekt. All of the beggars kick up to some low-level gangster who gets them benefits, like hanging out in the Panda rather than sleeping on the street. This man wore a dusty old suit, but the striking thing about him was his head. On top of his normal-sized body he had the smallest head Vyacheslav had ever seen, smaller than a child’s.

Vera passed Rafik the vodka and the balls, all gleaming white except for the yellow cue. She did not look at Vyacheslav now. Her eyes made big detours all around him.

“Have a pull with us, Vera,” Vyacheslav said.

“On duty,” she said. She turned her back to them and did something with the bottles on the wall. She was playing aloof but Vyacheslav knew that if he hung around long enough, she’d take him back to her apartment, which would be nice, but then, after, she’d want to talk and the last thing Vyacheslav wanted was to talk. What Vyacheslav wanted was to smash some balls.

“Another glass,” Rafik said.

Vera said, “I already told you I’m—”

“Not for you, Verochka. For our peanut-headed buddy here.”

She set another glass on the bar and hurried off to take an order from some foreigners playing American pool. What a joke American pool is. They play with miniature sticks on a tiny table with a bunch of tiny multicolored balls, a bunch of toy balls, just like between their American legs. Fitting.

Rafik and Vyacheslav did a shot with the small-headed man and then Rafik said, “Amerikanka time,” and they took the table that the small-headed man claimed was his.

Rafik racked, and Vyacheslav aimed. Russian billiards is a real pool game. The table is as big as Russia itself. Nine time zones long, eleven before Medvedev took two of them away. The cues are as long as cane poles and solid as birch trees. The balls are man’s balls, as big as grapefruits, sixty-eight-millimeter grapefruits.

Vyacheslav wanted to smash the balls across the room, to shatter the bottles behind Vera, to take out the cleaning lady still asleep on her mop, to crash them through the claw-toy machine, to carom them off the kneecaps of the foreigners playing their bullshit eight-ball. He held back. The break in Amerikanka must be soft, not even a kiss, a peck on the front point of the triangle. Several balls trickled toward pockets.

“I’ll tell you right now, and I mean it honestly: you can hide out at my parents’ dacha. They’re too old. No one is ever there,” Rafik said.

“And stay there for the rest of my life?”

“Stay there for a while. Grow some nice potatoes and black currants. Soon they’ll stop looking for you. Don’t get your ID checked.”

“I’ll get caught and it will be worse. I wouldn’t be able to see my mom. But thank you.”

Rafik shrugged and made a production of putting on the little black glove with two outpouchings, one that covered his pointer finger and the other that covered his thumb.

“Do you always play with panties on your hand?” the small-headed man shouted. “Hope you washed them first!”

Except for the break, everything has to be drilled in Amerikanka. The pockets are only four millimeters wider than the balls.

Rafik and Vyacheslav looked at each other and smiled. With the delicate strip of fabric connecting the two outpouchings, the glove did look a little lingerie-like, Vyacheslav thought, but he didn’t say so.

Rafik took a bad shot with a cigarette wedged in his mouth and missed, leaving Vyacheslav just what he was looking for: a straight-on drill into the corner. Except for the break, everything has to be drilled in Amerikanka. The pockets are only four millimeters wider than the balls. So unless you drill it, it ricochets out for sure.

Vyacheslav drilled it with follow, sinking the ball with this gratifying whoof-plunk—a sound he loved, a sound he felt more than heard—and leaving the ball he’d just used as the cue right there for a repeat. The constitution of Amerikanka declares all balls equal. The yellow ball starts as the cue but after that any one can take its place and any one can be the object ball at any time. Race to eight to win the frame.

He made the mistake of looking around for Vera. There she was making a show of flirting with the foreign guys. When she saw him looking she accepted their offer of a drink. She was especially handsy with one guy wearing a baseball cap that said Brooklyn Nets on it. Was that Prokhorov’s team, the one that Kirilenko played for? It distracted him enough and he was just off on a gimme. The ball ricocheted out of the pocket.

Looking back Vyacheslav should have just gone into the army the first time. Nothing was happening then. There was a crisis. There were no jobs. It would have even given him something to do besides fish and hunt mushrooms. He’d be out by now and would have missed this whole new clusterfuck. It wasn’t official but everyone knew where the soldiers were going. And this was just the beginning. What would it look like by the time he got out of training and headed for the front lines? Who exactly would he be fighting there? Guys who spoke as clean Russian as he spoke? His actual cousin whom he hadn’t seen since he last visited his aunt and uncle in Odessa when he was sixteen? Maybe he would kill some fascist or Western stooge or maybe he’d kill his actual cousin—would he even recognize him as he was shooting him?—or all three, and probably he would die there and they’d bury him secretly in some park across from a proper cemetery where young boys trampled over him in their sneakers without even knowing it.

Anyway, it didn’t matter. At this point just let it be. All he wanted was to forget it, and he wanted to smash more balls, and he wanted to beat Rafik, and he wanted maybe a quickie with Vera, and then he wanted to go home and eat the chicken hearts with pasta that his mom made for him before offering himself up as canon meat at the military enlistment office.

Rafik took the ball Vyacheslav had sunk and placed it on the scoring slot. Then he carefully sighted up his shot. He moved the cue back and forth across the fabric of the little black glove.

“I told her you’re going to the army tomorrow,” Rafik said. “She said it’s not her job to give a fuck about you anymore.”

“Quit masturbating, pinkie!” the small-headed man shouted. The ball went down, and Vyacheslav removed it to the scoring slot. They were even, and Rafik had his own gimme ready to fire. “Money shot!” the man said and he got up and thrusted. Rafik missed. “Wake up, pinkie,” the man said. “Amerikanka is too much for you. The little tables over there are more your speed.”

“I require more inspiration,” Rafik said.

Vyacheslav and Rafik drank the rest of the 500 grams in a quick series of shots and then Rafik went to the bar where the foreigner in the Nets cap was sitting talking to Vera and came back with the carafe refilled.

“I told her you’re going to the army tomorrow,” Rafik said. “She said it’s not her job to give a fuck about you anymore.”

Vyacheslav lined up his favorite shot in which you sink the cue by caroming it off another ball. It requires a kind of logic completely counterintuitive to anyone trained in American pool.

Angle.

Spin.

Force.

Redirect on the carom.

Whoof-plunk.

“Shit,” Rafik said. He added the ball to Vyacheslav’s scoring slot.

“Why is this game called Amerikanka?” Vyacheslav asked. “Why ‘American girl’?”

“That’s a good question,” Rafik said. “Actually it’s just the name of the game. You play pool, you play ‘American girl.’ You play Amerikanka.”

“We play it all the time and it never made sense to me. Then I started thinking about it. We call all kinds of things foreign girls. A German car is a ‘German girl,’ and we call a Japanese car a ‘Japanese girl.’ But a Ford is not an Amerikanka. Our pool game is.”

“A ‘Lithuanian girl’ is one of those long-handled scythes,” Rafik said. “And there’s a special grinder called a ‘Bulgarian girl.’”

“An excellent prune plum is a ‘Hungarian girl.’ And gymnast slippers are ‘Czech girls.’ Flip-flops are ‘Vietnamese girls.’”

“Of course, a little knife is a ‘Finnish girl.’” Rafik patted his hip where Vyacheslav knew he kept his finnka clipped to the waist of his ridiculous shorts.

“What do you make of it?” Vyacheslav asked.

“I don’t know. It’s an unanswerable question. Why do we call anything anything? You thinking about girls on your last night, huh?”

“And what’s a ‘Russian girl’? Just a Russian girl, who might give a fuck about you for a little while and then not. No slang for her.”

Vyacheslav searched the room for Vera again. She wasn’t there. He looked for the foreigner with the Nets cap. He didn’t see him either. He told himself that he didn’t care what they were doing. And he told himself that he didn’t care that he was going into the army tomorrow. And he told himself that he didn’t care where he was buried. And he told himself that if he had to kill his cousin he guessed that he would kill his cousin. He slammed another ball in and another and another, each one harder than the last.

The small-headed man loved seeing Rafik lose. The small-headed man was out of his mind drunk. He danced around their table, shimmying, hands in the air, wiggling his thin ass, and spinning in a circle, jeering and laughing.

“Hey, pinkie,” he cried. “Maybe you should try shooting with your pencil dick!”

Rafik took a drag on his cigarette and turned to Vyacheslav. He said in the calmest possible voice, “I am close to sticking my Finnish girl in this asshole’s gut.”

Rafik took all the balls down from the scoring slots and racked them. They did another series of shots from the carafe.

Vyacheslav watched the small-headed man. He posed no threat. He was a small-headed annoyance. But the more Vyacheslav looked at the man the more he became convinced that the man’s head was close to if not exactly sixty-eight millimeters, a dimension that was admirable for a billiard ball but horrific for a head. This gave Vyacheslav the idea, and once he had it he could not let go of it.

He wondered what time it was. Without windows it was impossible to tell inside the Panda.

He tapped the light over the table with his cue and it swayed. He sighted up the next break. He started to see, as the shadows of the light danced across it, the man’s features on the yellow cue ball. He broke and the ball on the left point of the triangle dropped in. He walked quickly to the other side of the table and slammed a ball with the man’s beady eyes, colliding it with other balls sprouting his ears and his bent nose and his toothless smile.

Vyacheslav wondered why something like this hadn’t occurred to him before. Sure, he had considered jail as an option but always in connection with robbery or burglary, and he didn’t like the idea of being labeled a thief. Assault was different. No one wanted to live life on the lamb, as Rafik had proposed, but if he went to jail for a while, a year or a couple maybe, the clusterfuck would settle down. At the very least it’d buy him some time. Then later he’d do basic training and get sent to some base to move rocks or shovel shit or whatever the army did when there wasn’t a war going on.

“Come over here, pops,” Vyacheslav said to the small-headed man. He poured him a shot and the man kept dancing and pointing his fingers at Rafik and smiling.

“Hey,” Rafik said, “the word for buckwheat sounds an awful lot like ‘Greek girl.’”

“Oh,” Vyacheslav said. “I heard something about that. Buckwheat used to come from Greece, I think.”

“And a top cut of meat sounds like ‘Korean girl.’”

“Koreyanka. Koreyka. Koreyanka. Koreyka. I can’t explain that one.”

“I just remembered,” Rafik said, “my grandfather used to call his tile stove a ‘Dutch girl.’ ”

Vyacheslav pretended to sight up the break, but now he wasn’t concentrating on the balls at all. The small-headed man kept dancing and taunting and Rafik was less and less successful at laughing the spectacle off as he searched his phone for more things referred to as foreign girls.

He didn’t regret that there would be no quickie. He regretted that he would miss out on his mother’s pasta and chicken hearts.

Vyacheslav glanced at the bar where Vera had suddenly appeared, walking back from the bathroom with the guy in the Nets cap. She was looking dead at Vyacheslav. Good, he thought. He wanted her to see.

He didn’t regret that there would be no quickie. He regretted that he would miss out on his mother’s pasta and chicken hearts.

Thinking of the chicken hearts made him doubt. There was a chance that whatever low-level gangster the man kicked up to would want to handle things without the cops. In that case Vera could, if she properly understood, actually help by calling the cops. But then there was no guarantee the cops would lock him up. How much time does one get for assault anyway? He didn’t know. And maybe the cops wouldn’t care about some homeless guy? It’d be more straightforward to stand on the sidewalk outside a museum and sucker-punch an obviously decent person in the face. That he couldn’t bring himself to do.

But even if this failed to keep his own ass out of the army, Vyacheslav would still be doing the man a favor, saving him from finding Rafik’s Finnish woman in his gut. As if coming into a billiards place with a head the size of a billiard ball was not enough.

Maybe his mother would bring him some pasta with chicken hearts in the jail. Probably she would. He would have to remember to get Rafik to ask her. He would have to remember to tell Vera to call the cops if she ever gave a fuck about him and to tell Rafik to have his mother bring him pasta with chicken hearts in the jail.

“It says here that plaid is sometimes ‘Scottish girl,’” Rafik said. “That makes sense. From their kilts. But wait a second. Don’t the men wear the kilts? What the fuck?”

Vyacheslav wasn’t listening anymore. He wasn’t doubting and he wasn’t worrying about the army or shooting his cousin or being buried somewhere or why Russians called things foreign girls. He was already feeling the whoof-plunk.

He nudged the light over the top of the table with his cue again. Then he swung when the man did a kind of pirouette, and only then did it occur to Vyacheslav that the man’s head might even be smaller than a Russian billiard ball. Maybe even the toy size of one American testicle. Though more than likely this also was a trick of the light.