A middle-aged man wearing a plaid shirt, denim overalls, and a white driving cap is building a cabin before a backdrop of snowy mountains and a turquoise lake. The blade of his handsaw makes a steady sound, cutting through a peeled log stroke by stroke. As the title of his film reveals, Dick Proenneke is Alone in the Wilderness, although from my spot behind the counter, I see how Dick draws a crowd: every seat in the video nook is occupied, and men—mostly older visitors who seem past their cabin-building years—stand behind the benches, arms crossed. All day, every day, tourists consume Dick’s story, which continually unfolds since we keep him on auto-repeat.

It’s summer, and I’m working as a park ranger at a visitors’ center in Fairbanks. I dole out brochures for lands across Alaska, including Lake Clark National Park, where Dick’s cabin on the edge of Upper Twin Lake is now a historic site. Dick is a star, with a strong presence on the park’s website and his own handout that I’m constantly photocopying since it flies off the rack in the video nook. We’ve run out of DVDs, so a gray-haired Australian buys Dick’s book. “He’s magic,” the man sighs, and I have to agree.

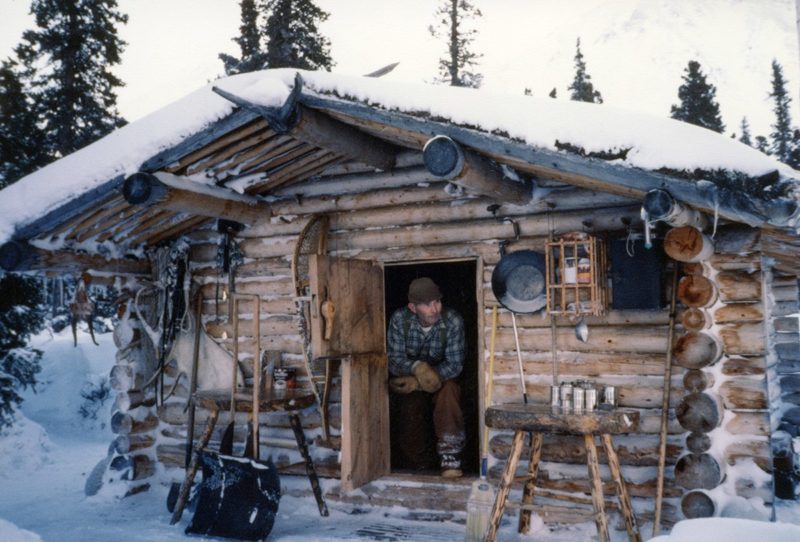

One of my coworkers says Alone in the Wilderness is the only movie she’s seen over and over and not come to hate. It captivates me, from its opening shot of rosy alpenglow and Dick’s calm declaration: “It was good to be back in the wilderness again. I was alone, just me and the animals.” As the film begins in the summer of 1968, Dick is fifty-one and preparing to build the cabin where he will live for more than thirty years. Other than supply runs by the pilot Babe Alsworth, Dick will be entirely alone, just himself and his tripod-mounted camera.

I confess to my co-workers what seems an obvious desire: I’d love to be Dick Proenneke. Who wouldn’t want to live alone in the wilderness? They don’t, as it turns out. “He seems so lonely!” Anne bemoans. “Too many chores,” Adia adds.

She’s right—he does do a lot of chores. “July the thirty-first,” Dick announces. “Tin-bending day.” He’s cutting down metal gasoline containers and transforming them into common household items. “Made a water bucket, a wash pan, a dish pan, a flour pan, and storage cans,” Dick rattles off, so that I am astonished, once again, by his productivity. In the video nook, the crowd appears captivated. It would be hard to script a duller TV moment, but Dick makes even tin bending compelling because what he is really doing is sidestepping the modern world, tin shears in hand. Then he realizes he needs a spoon to pour batter onto the griddle. An hour later, he’s carved a spoon.

The writer Sam Keith, who befriended Dick when they both worked at an Alaskan naval base, edited Dick’s journals and in 1973 published One Man’s Wilderness, a chronicle of the construction of Dick’s cabin, which became an Alaskan classic. Five years before my job in the visitors’ center, this book introduced me to Dick Proenneke when I picked a copy off a sale rack in Fairbanks and brought it to my government job counting fish on the Alaska Peninsula. I did not know it then, but that job would be the closest I would come to living Dick’s dream life. I shared a cabin with a coworker in a river valley surrounded by snowy mountains and next to a lake. A pilot flew in supplies, and two months later he flew us out. In between, we counted fish, roamed, completed chores, and read. On days when the clouds lifted, I admired a hanging glacier. One day, while the wind blew forty, I curled up in my sleeping bag and began Dick’s book. The salmon were running, and from my window I watched bears fishing. Reading the book in such a remote place fired my imagination, even though building a cabin seemed out of my reach. Dick first visited Twin Lakes in 1962 and vowed to return. Five years later he did, cutting logs for his cabin, which he built the following summer. I lived and worked at the fish camp for three summers, in a cabin I did not build, and never alone. I have never been back. Dick served in the US Navy in World War II, worked as a carpenter, and retired as a diesel mechanic and heavy-equipment operator from the Kodiak Naval Base. Meanwhile, I’ve counted fish and doled out brochures.

I have another ten years to go until I’m as old as Dick was when he built his cabin, but I cannot imagine that will be enough time for me to gain his level of competence. I’ve settled on a compromise, visiting the wilderness but not living there. Instead I live down a dirt road in Fairbanks. My property is part of an old homestead, and I’ve been fixing it up for ten years. Through years of renovations, I lived with ripped-out walls and lumber piles in my entry. Construction starts and stalls, and I’ve entered a hazy phase of perpetual chores. I’ve put in a garden and grow vegetables. I pick berries with an obsession that would perhaps be better applied toward carpentry. I am not alone in the wilderness, but I am alone most of the time.

As part of my job, I lead an interpretive walk about pioneers of early Fairbanks. I carry an iPad to show visitors photos from the early days, when pioneers carved up the forest and created a town. I point at the busy road bordering our parking lot and pull up a photo from 100 years ago, when there was nothing but a string of cabins and gardens. We visit a surviving cabin, a token souvenir from what was demolished to build the visitors’ center. There is a fake outhouse in the yard, and tourists practice driving Segways in the parking lot before their tour along the bike path.

The frontier has largely vanished from Fairbanks, and I find myself desperate to convey how self-sufficiency, resourcefulness, and other frontier values live on in small ways. The tourists want to hear this, too—they are more drawn to Dick’s film, which shows the Alaska they want to see, than they are to the bingo parlors and box stores found on streets near the visitors’ center. When I tell the story of the past, I bring in my own story. I don’t have plumbing. I haul water or melt snow on a wood stove. I split wood. I play dodge-the-moose in my driveway. When I return to the topic of the historical cabin, one lady insists my life is more interesting. “You are a pioneer!” a man claims. No, I am a cabin yuppie, with Internet but no plumbing.

In the time I’ve been gone for my interpretive walk, Dick’s almost built his cabin again. Eleven days for him, and he’s notched and assembled the felled trees with the precision of Lincoln Logs. To trim his windows, he makes his own boards using homemade tools. Dick takes a brief break to sweep wood chips. “Quite a pile for eleven days’ work,” Dick notes, and I shake my head in admiration. I’ve spent longer reading an instruction manual.

This summer, one of my projects is to finish my outhouse, which I began two years ago. Wishing to create a handcrafted treasure, I used salvaged scraps cut from the outside of logs and spruce poles disfigured by spherical goiters called burls. My wood suffered from unpredictable unevenness, and the first snow of the season fell as I erected the corner poles, bracing them against my body while sledgehammering five-inch spikes. When I finally squashed the last spike into the wood and stood back to celebrate, I realized the outhouse leaned. I added more braces, but when I climbed the steps, the contraption shook. I consoled myself by using my best boards for the seat, but when I cut out the circle in the middle I understood I’d made a mistake—cutting a hole in the boards ruined their integrity, and the seat collapsed inward. When my neighbor inspected my progress, he declared, “It’s crooked!” Dick built his outhouse in a day. Sometimes I despise him for his never-ending efficiency.

I turn away to help a visitor, and when I next notice Dick he is working on his roof. Here he makes a rare concession to modern technology by using tarpaper and polyethylene, but these artificial materials are buried when Dick tops off the roof with moss-covered sod. Dick’s been busy lately, excavating thick rectangles of moss. I’ve done this before too, when I built hiking trails. I carried chunks of earth on my shoulder, the cool moist moss resting against my neck as dirt trickled down my shirt. Dick, of course, is more efficient—he builds a wooden rack so he can carry two moss chunks at once. When the film shows a close up of Dick shoveling, the moss leaps out of the ground. It’s an illusion, an effect of the speed of old film, but it seems in line with Dick’s capabilities.

By now we understand that Dick is crafting a masterpiece. I love the concept of mastery, but as I flit from activity to activity, it’s hard to achieve more than mediocrity. Watching Dick Proenneke, no one can doubt his accomplishment. Who else knows how to make a wooden door, complete with homemade wooden hinges? “Too many men work on parts of things,” Dick muses. “Doing a job to completion satisfies me.” Dick has a knack for folksy statements, and because of the life he leads we accept this as wisdom. Moments like this suggest the film—and the fandom that has grown around the memory of Dick Proenneke– has never been about making door hinges. Judging by the crowds in the video nook, Dick has achieved something mythical: he seems happy. Alone in the Wilderness is less a story than an accumulation of moments: the pouring of batter on a griddle, the plink of a blueberry into the container, sipping coffee while gazing at the lake.

After his first night in his finished cabin, Dick reports his best sleep in a long time. He had been rushing under the deadline of winter; now his leisure increases. It is almost painful to watch how joyfully Dick spends his time. “I am getting hungry for a fish,” Dick announces, so he strolls to a nearby stream and pulls out a fish. Not that he is without work; the sound of his unceasing saw often echoes from around the visitors’ center.

“This business of taking wood out of the savings bank and putting none back has been bothering me to no end,” Dick announces. This line often makes me cringe because I’ve been wondering if I live too much on credit, trying to do too much, to be more than one person, to experience everything rather than accept limits. I whirl through life emanating stress and leaving uncompleted projects in my wake. I seek simplicity but sow complexity. I see a wood pile as something to tackle, but Dick seems to enjoy work, as long as it is of his choosing.

“I suppose I was here because this was something I had to do,” Dick muses. “Not just dream about it, but do it. I suppose, too, I was here to test myself. What was I capable of that I didn’t know yet?” His cabin completed, Dick can’t help but test himself in other ways. Today he is away, off to take a “long look into the heart of high places.” Loose rocks force Dick to pick his way across the slope, a hand down for balance. “One bad step, and I would keep right on going down the mountain,” Dick considers. “But risk now and then is good for a man.” While Dick sidesteps across the snow, a young couple snaps a selfie by a map of Alaska that’s adjacent to the TV. The visitors’ center is busy, the guests gathering their brochures or flowing from the exhibits in the replica cabin, complete with a chest freezer filled with fake packets of moose and fish.

In mid-summer, new exhibits arrive, along with installers who measure walls and drive a motorized lift whose beep drowns out Dick. Three installers apply a giant sticker across twenty feet of wall, transforming the space into a green aurora. The theme is Getting Out in Alaska, so props like bicycles and an orange inner tube are fastened to the wall until the area begins to look like a yard sale. A decal orders: Ask us about winter!

Dick is enjoying his first winter at Twin Lakes, declaring it even better than summer. He hunts Dall sheep and builds a sled. He shovels snow and goes exploring. One day, he’s snowshoeing around the shore when he comes across wolverine tracks. Organ chords crescendo from the soundtrack, because the wolverine has been eluding Dick all winter. If I’m not busy, I especially like to watch this scene, because I’ve been trying to see a wolverine for fifteen years. The creatures are so elusive that even wolverine researchers rarely see them. Dick’s luck is about to change, however, because the wolverine is rolling down a snow slope, looking silly. “And then there he was, the one with the ferocious reputation,” Dick announces, as giddy as his understated tone allows. “He didn’t look so ferocious to me.” The addition of the wolverine is almost too much—the entire film feels like an enactment of my fantasy world, and with the entrance of the animal I most want to see, the film teeters on the boundary between the real and the fictive, as if the unfolding images are emerging from my unconscious.

There is a stuffed wolverine above my desk in the visitors’ center. I wish it were not there, because I hate seeing a dead wolverine every day when I have been trying for so long to see a live one. The life spirit is gone, leaving a corpse that is displayed as decoration. Nonetheless, when tourists ask to photograph the wolverine, I smile and step aside. Perhaps I also seek a touchstone to help me connect with an elusive spirit; lately I’ve been wondering if keeping Dick on auto-repeat is itself a form of taxidermy. The man who paddled a canoe and sawed logs is not here, although we do our best to package him up in DVDs and glossy books, to contain him forever in 1968. He is ours now, to mold into our own kind of creature.

Occasionally I remind myself of the obvious: that the film is edited. Even the smooth voice reading all of Dick’s lines is not Dick; it belongs to producer and singer Bob Swerer, who helped write the lines. The real Dick Proenneke doesn’t make easy listening. I’ve heard him on other DVDs, and he has a voice that squeaks and accents words in unconventional places. The producers have sent out a pinch-hitter, a narrator whose voice won’t get in the way of the story. Of course, the entire film is an act of creation that began the moment Dick decided to bring a tripod-mounted camera. Dick decides which images to capture. Dick stands with one hand on his hip and the other resting on a vertically held saw, admiring the cabin. The camera is behind him, taking it all in.

And there is the sadder way in which Dick’s film feels like taxidermy—Dick is dead. He died at the age of eighty-six in 2003, the same year the film began appearing on public television. Near the end of the film, the chronological time leaps thirty-five years. In slow motion, Dick swivels to face the camera, his expression caught in a peculiar smile like a sagging jack-o’-lantern. This is no longer the middle-aged but nimble man who carried logs on his shoulder. We learn that Dick bequeathed his cabin to the National Park Service. The film plays upbeat music while a new narrator assures us that Dick’s spirit will always linger in the perfect notches of his logs.

Perhaps the movie must relent to the passage of time and reveal the “end” of the story, but I often forget that the movie has a chronology, that it is the story of a year. I feel I am watching Dick in a present that cycles through seasons and begins again. When the visitors’ center is quiet, he keeps me company. “Dead calm and zero degrees,” Dick says, and I know he is headed to the lake with his water bucket. There are three inches of ice to chip through and walkways to keep clear. I have yet to pick up tin shears or carve a door hinge, let alone build my cabin; but in his continual company, I begin to feel the cadence of his work.

On his desk, Dick kept a map in which he stuck a pin at his intended destination every time he set out from the cabin, a precaution in case he vanished. Over time the map became a marker of accumulated outings, each pin hole a small plink like a berry deposited a bucket. Instead of the image of the elderly Dick Proenneke, with his awkward expression as he struggles to face us, I would edit the video to end with Dick snowshoeing through the woods. He comes across a spruce tree with a giant burl and knows what to do: he will transform the burl into a table. He cuts off the burl flush with the tree—a tricky job with a handsaw, but of course Dick makes it look easy. For a moment we watch Dick and listen to the saw, a sound that I associate with him because no matter where I am in the visitors’ center, I hear him sawing. When he is satisfied, Dick straps the burl slabs to his pack board and heads back to the cabin for lunch. The burl on his back makes him look like a turtle as he walks away from the camera and into the woods. In the cabin there is a coffee can filled with cranberries, and cranberry syrup to make.