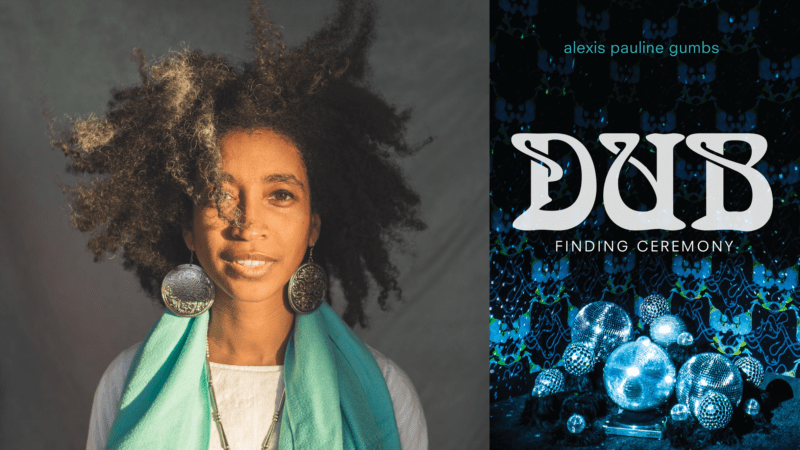

Dub: Finding Ceremony is the third and concluding book in a poetic trilogy by Alexis Pauline Gumbs. The first book, Spill, is a collection of experimental works exploring Black feminism through imagined embodied scenes of fugitivity—Black women seeking freedom from gendered and racist violence. M-Archive, the second book in the experimental triptych, tells a researcher’s story after the end of the end of the world, reconstructing the truth through artifacts of survival and possibility in a post climate-crisis state. Dub continues in the trilogic legacy of genre-breaking with prose poetry that channels the voices of ancestors and offers wisdom stories of the diaspora that break western constructs of time and space.

With the voices coming through porous walls of ocean and land, Gumbs identifies and shares marine life as portals of Black feminist genius and living, breathing history. Each book deepens, builds, and interrogates scholarship, storytelling, and poetry in an ongoing dialogue with the works of leading Black thinkers and scholars Hortense Spillers, M. Jacqui Alexander, and Sylvia Wynter.

— Lisa Factora-Borchers for Guernica

Guernica: How did you create a book of this breadth and imagination by listening to your ancestors?

Alexis Pauline Gumbs: It was an intense embrace of “what looks like crazy.”

There are women ancestors in my lineage who I know for a fact were institutionalized in mental hospitals; my great grandmother died in a mental hospital. Part of my commitment to listening to my ancestors and cultivating forms of listening that I need in order to be the type of artist I am comes from understanding the time that they lived in, the patriarchal family structures they survived. These women in my lineage were punished for listening to themselves.

When it comes to my great grandmother, in particular, she was honestly trying to fight ableism. That’s my lineage. And I’m proud of that clarity and resistance. And what are the ceremonies that are required of me in order to continue to be that and resist institutionalization—in all the ways I resist institutionalization? Not only mental hospitals, but universities, corporations. Part of my life’s purpose is to say there is another way for us to do this and there are things that shall not be contained by these institutions. A lot of that is accountability to my great grandmother and my other ancestors who were forcibly contained in harmful and deadly ways.

I just feel so happy; I feel my ancestors working to get me to the other side. I’m standing out here listening to whales and bacteria, being able to actually perceive our connection to everything and feel how powerful that is. I’m reclaiming the power of “hearing voices.” What if people were that powerful all the time? Most of the institutions we know of would fall away. There wouldn’t be a use for them. We certainly wouldn’t tolerate all the forms of oppression that keep us repressed if people, all the time, felt that profound connection. That would be the end of the civilization that we know and the return to what maybe we actually deserve. That’s how I see it.

Guernica: Something I noticed as I read Dub was the impact of your use of the second person, the “you.” At first, I heard it as your voice which made me feel like an observer—you are the listener, oracle, prophet able to tap into something and I was there to observe. But by the end, I felt like I could hear it and I considered the possibility that it wasn’t solely you and your ancestors, you and the whales, you and the messages. They were, perhaps, messages from all my ghosts, from my people, and these were all of my things trying to come through. It reminded me of how I felt after reading Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, which had a literary transference of power to the reader.

Gumbs: That’s it. It’s oneness.

I’m not interested in the idea of the reader as separate. There is another layer of intimacy that is possible and I want readers to know that this is not about learning about me or even learning something from me that I know and can tell them. It’s about the opportunity for them to have that experience, “Who is this? Is this about me? Did I write this?” I think that’s also a part of what I am trying to learn. How can I relate to anything: the ocean, whales, other people in the world? How can I relate in a way that I am called to wonder?

[For] any of us moving through the airport, we could just decide that the person across from us has a message for us. We can just decide to see an oracle at all times. It’s constantly happening. At some points it could be overwhelming to be perceiving every little thing because we don’t know that we can but all of it is speaking to us. Our power is that infinite. If we decided to listen, it really is that simple. And the question becomes where is it coming from, is it really for me, what is it? These questions are exciting and interesting and I think destabilizing, usefully destabilizing, but ultimately you notice or you don’t.

Guernica: When you first started Spill, did you know you were working on a multi-book collection? How did you know to make it a trilogy?

Gumbs: I didn’t know that I was going to write a three book collection, but I decided to engage in a morning writing practice, specifically with these theorists Hortense Spillers, M. Jacqui Alexander, and Sylvia Wynter–in that order. I knew there was an intimate quality to their work that I thought I could exercise, not for producing books but for clarifying my relationship to my intellectual writing. They are three theorists and scholars who haven’t written a book that’s like a scholarly monograph that they were expected to write (which I, too, felt I was expected to write). I was responding to these expectations.

I thought, I am going to be with these theorists—who I actually cite over and over again in my own intellectual writing, and see what works. I didn’t know if anything in that process would be shareable, but I knew it was going to offer me what I needed.

Guernica: Could there be a fourth book?

Gumbs: I am definitely making more books for sure. But I think this is a particular ceremony for me. Of course I will continue to engage other Black women writers. Of course I will continue to write first thing in the morning because that’s what I love to do. But as for the triptych, this is it. It actually has been really interesting to get to the end of these three because that was a decision I made probably at least seven years ago.

This writing has done something in my life, both as a writer and in my communication to the world about what I think writing even is. The writing that I’m doing now has a different function, but I don’t know what it is yet, just like I didn’t know what the full impact of the other writing was going to be. So even though there are infinite Black women writers and theorists who I always think about and I’m sure I will be in deep conversation with, I don’t think I will be as specific about citing one person on every page like I do for all three of those books.

But I might.

It’s all listening. It’s ongoing listening. For me there’s a lot at stake in it and I feel grateful to even have the space for that. It’s something I had to do while I was in graduate school. I had to reclaim my writing practice for myself and the actual practice of it. I have to know that it’s worthwhile for me whether anyone ever reads it.

Guernica: Were current political crises a part of your consciousness as you wrote Dub or do you think the relevance is a natural output of your daily meditations?

Gumbs: I wrote M Archive during the Obama presidency and M Archive came into the world when Trump took power. Many people asked if I wrote that because the world was coming to an end. But I didn’t know that was going to happen!

I think it’s interesting because I wrote it as a daily practice, as a guide for me for that day, and whatever’s going on in the contemporary moment is part of that day. But also it’s about everything being connected.

There is a way that whatever is now is not only now, and that’s important to me. We seem to be perceiving so much of what is happening all the time because of the technology that we have right now. And that’s true across all of time. Even if I can’t perceive what happened throughout all of time, it is all connected. I feel profoundly connected to our species but I feel connected to other species. The listening that I’ve been doing has really shifted my relationship to how words impact me.

There is a longing that I felt for a long time to be able to do more than react to a contemporary media articulation of the situation, knowing that that’s already limited by the particular moment and how people are talking about it or the hegemony of how the media escalates. It’s the part that Sylvia Wynter is so helpful for. It means that how I’ve learned to think or who I think I am or how I think I’m related to anything else can change and must change.

Guernica: You have long said that Black feminism is your spiritual practice. Has that changed in any way?

Gumbs: I feel what brought me to Black feminism and has me in the practice of Black feminism faithfully—as the thing I’ve been most consistently committed to so far in my life—is that its core is interconnection. It is a philosophy and political imperative based on interconnection. Black feminism is my spiritual practice and for sure the condition of possibility for my freedom as it exists in my lifetime right now.

I realize now looking back that I engaged whole heartedly in an apprenticeship to Black feminism. Black feminism had something to teach me and I was an apprentice, learning [from] all these people, collecting mentors. And now I’m not a Black feminist apprentice, I’m a Black feminist. I’m in a different part of the process now. I’m a Black feminist expert now and it’s still a spiritual practice that has a lot of humility.

I’m also a marine mammal apprentice. I don’t know how to be a marine mammal. Now I really have to learn, but at one time I didn’t know how to be a Black feminist. I’m really humbled and need to learn from those beings who have long term practice—having lungs and living in water, who have adaptations around salt water and fat. Yes! What I see in marine mammals is what I saw as a child and preteen in Black feminism. I see the salvation of the world in it.

If we related to water in the ways that are exemplified by these marine mammals, there is something really important that is possible there and very necessary, and certainly a threat to the status quo.

If a person could really learn how to live and learn in interconnectivity, and if we meaningfully did that, yeah, so much would be possible. This liveable, lovable world would be possible. That’s what I let guide my life.

Guernica: What beautiful and rare connections you embody through Black feminist praxis: the practice of learning, unlearning, listening, and offering your voice in the continuation of your ancestors.

Gumbs: Dub eviscerated me from my own origin story. I have understandings of who I am that were based on what I call a static ancestral relationship. What happened in the writing of Dub is that I realized that I’m in a dynamic ancestral relationship with all these people I’m related to—and all the ocean I’m related to, and all the bacteria, and all the whales and coral. It’s a dynamic ancestral relationship because it’s like the rest of life: It continues to transform in multiple directions, which is why I have to practice everyday.

It’s a much more dynamic relationship than I understood at first and that’s what can be honored through ceremony, and an ongoing practice of listening which is different than when I say, “I know the story and I can just tell it.” It’s not the same story.

The stories I’ve been told my whole life about who my ancestors are did not survive. They were starting points of listening. They were certainly things I thought about in the process but my relationship with my ancestors whose names I know and whose names I don’t know are not, none of them, the same as they were when I started writing Dub, including my father. That’s what I mean by destabilizing evisceration and unlearning myself because if they’re not who they are, I’m not who I am. It’s more than a notion, that’s what my mentor Cheryll Y. Greene, who is now an ancestor, said often. But in her words I also hear “more than an ocean.”

Guernica: Everything is about listening. Is it possible for you to describe, literally, how you heard it?

Gumbs: How I heard it? It’s like…I heard it like someone whispered in my ear or like looking in my own eyes in the mirror and, “YOU KNOW THIS RIGHT NOW.” Or from inside my own chest.

Sometimes what I’m hearing is what my own questions are. That’s what I wrote down. And sometimes it’s something they would tell me in their language, if they were living and I was able to witness what they were living. Other times I was listening to an aspect of them that wasn’t like their life, but only sits in their relationship with me now. And so that voice is really shaped by what I can audibly hear. It’s authentic to the relationship more than it’s authentic to their time period or their literacy level or any of that.

I heard it in a lot of different ways and had to put it down how I could put it down, understanding that there wasn’t anything I was trying to recreate. I was just holding it, writing it down. Either passing it on, or not, but certainly I had to face it, whatever it was.