“I should have known better,” Alex Kotlowitz told me, explaining that he had intended to spend six months reporting his new book, An American Summer: Love and Death in Chicago. In reality, he said, it took more than two years—though one could argue it’s actually taken closer to 30.

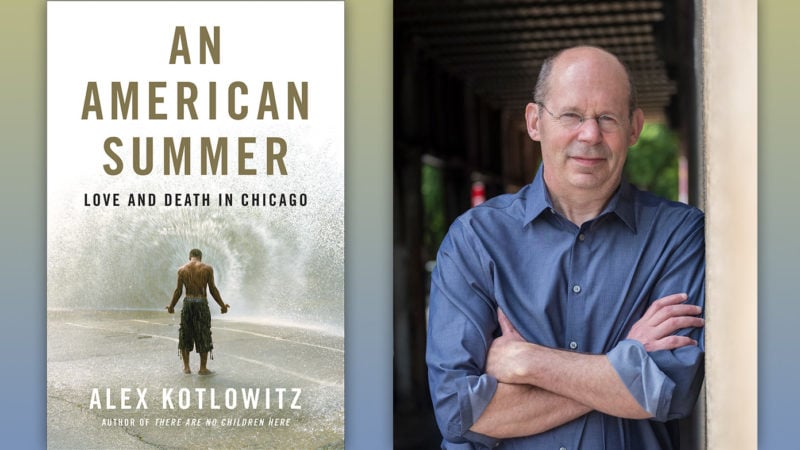

Kotlowitz’s 1991 book There Are No Children Here—about two brothers, Lafayette and Pharoah, growing up in a Chicago housing project—was named one of the New York Public Library’s “books of the century.” In the years since, his prolific journalistic output has spanned genres while revolving, more often than not, around his adopted hometown. Kotlowitz co-produced the Emmy-winning documentary The Interrupters, about a violence intervention program in Chicago. He also co-reported the Peabody-winning This American Life episodes on the South Side’s Harper High School.

An American Summer chronicles a three-month period in 2013 that saw nearly 1,000 people killed or wounded by gunfire in the city, and is constructed as a series of stories about those left behind. In addition to introducing a diverse array of new characters, Kotlowitz uses An American Summer as an opportunity to revisit characters from There Are No Children Here, Harper High, and The Interrupters. The result is an intimate, harrowing depiction of what it is to live and love amid constant violence.

I first read There Are No Children Here in the summer of 2009, as I prepared to become a public-school teacher. I went on to teach in Chicago’s Cabrini-Green and Near West Side neighborhoods for eight years, and these experiences colored my conversation with Kotlowitz. Over hot tea in his Oak Park kitchen on a frigid, snow-covered January day, we talked about his evolution as a journalist, the perils of writing about communities that aren’t one’s own, the trauma and healing inherent in telling stories about violence, and why he’s stayed in Chicago so long.

-DJ Cashmere for Guernica

Guernica: Who do you want to read An American Summer, and why do you want them to read it?

Alex Kotlowitz: I’m always writing for an audience for whom this is unfamiliar terrain, an unfamiliar community. I’m writing for people to pay attention. So much of what I write, both in An American Summer and my other work, is about corners of this country that have been pushed aside and neglected. For me, the beauty of stories is they’re a really cheap way to travel, to spend time with people you otherwise wouldn’t meet. So that’s my most immediate audience.

But having said that, I also hope that people who’ve had experiences like those in the book will read it and feel less alone.

Guernica: What does it look like for you to have the folks in the book, and the folks who are in circumstances like those in the book, read it—versus, say, a New Yorker audience?

Kotlowitz: I can tell you a little bit about my experience with There Are No Children Here. I wrote that book because I was so angered by what I saw, and also kind of ashamed: how could I not know? And so I felt like readers, presumably, would begin the same way, with this sense of shame, and end with this sense of anger. But what I didn’t expect with was all the letters, emails, phone calls I’ve gotten from people who say to me, in one manner or another, “That’s my story. Thanks for telling my story.”

I used to think that the reason to tell stories, and the power of narrative, is that it brings you places you otherwise wouldn’t go, and introduces you to people you otherwise wouldn’t meet. But [stories] also give affirmation to your own personal and collective experiences. Stories make you feel less alone—especially with something like this violence, which feels so private. One of the things that struck me, working on this book, is how so many of the people I spoke to had never talked about this experience with anybody else. I think, in part, that’s because they didn’t know what to make of it. They assumed that only they had been through this.

Guernica: There is this sort of colossal, all-enveloping silence around gun violence in Chicago. And I’ve heard you talk about how one of the sources of that silence is that disenfranchised folks feel like their stories won’t even be believed. As a classroom teacher, I saw books like My Bloody Life and The Other Wes Moore fly off my classroom shelves on the Near West Side, because students were just blown away by the notion that there could be a book that was about them in some way.

Kotlowitz: There’s a story that Studs Terkel used to tell. He was in public housing—maybe working on his first book, Division Street—and he was recording a woman in the projects using this big, clunky, reel-to-reel tape recorder. He interviewed her for an hour. And then she asked to listen to the interview back. And he played it back for her. She said to him after listening to it, “You know, I never knew I thought that way.” And that’s what telling stories does. It makes sense of your story.

Guernica: I’ve heard you talk about Studs Terkel a few times. One of the things that you’ve mentioned in the past is his idea of writing about “the etceteras of the world.” I was really struck by that phrase. Do you feel like your subjects see themselves as the etceteras of the world? And if so, what does that mean?

Kotlowitz: I think what he was saying is that they’re people who were kind of dismissed by the rest of the world. They’re dismissed, the way you would do in a sentence—when you use that term, “etcetera,” you’re just sort of dismissing everything that would follow. Dismissed by the justice system, dismissed by the city at large, sometimes dismissed even in their own community.

Guernica: There are so many journalists that leave small towns and smaller cities to go live in New York. But you grew up in New York and have now been in Chicago for 35 years. What has living in, or just outside of, Chicago, meant for you, as a person and as a journalist?

Kotlowitz: For me, Chicago is America’s city. You find all the fissures within the landscape in the confines of Chicago, or the Chicago metro area. Clashes over race, class, the intersection of politics and money. We see that now going on in the city. It’s been a source of stories, but it’s also been this wonderful muse.

On a practical level, part of the reason I never moved back to New York—I don’t have any desire to now, but at some point I thought about it—was that I worried my inclination there would be to look over my shoulder at what everybody else was doing and think, oh, I should be doing that. There’s something nice about being removed from New York, and having access to these stories that others might not.

Like a lot of people, I have kind of a love/hate relationship with this country. And so, trying to understand what it is I love about this country, I couldn’t think of a better place to be than in the center.

Guernica: You’re a white guy, and you live in a nice house. I’ve heard you talk in the past about how journalists are always outsiders to some degree. And in this book, your outsider status includes your race and class. I’m wondering how your understanding of your whiteness and your social class, and your understanding of the way it impacts your work, has changed over the decades you’ve been writing.

Kotlowitz: I think I’m much more self-aware than I was 25 or 30 years ago. But the flip side of that is that I’ve also—for the past 25, 30 years—done a lot of reporting from these communities, spent a lot of time with a lot of people. So, I feel on some level that I’ve gotten to know the communities that I write about in An American Summer much better. Whereas when I was working on There Are No Children Here, it just really knocked me off balance. I felt this incredible sense of shame, and kind of disbelief: it can’t be really this bad.

I also remember, working on There Are No Children Here, when I was meeting the first few weeks with Lafayette and Pharaoh. They were twelve and nine years old, and I’d take them out to pizza in those early weeks. And the thing that really unsettled me was the violence, so that’s all I wanted to talk to them about. And I remember once, Pharaoh started talking about this Spelling Bee he had coming up. And I was really dismissive, and just said, you know, “No, I want to know about this.”

That is one of the potholes you fall into if you’re an outsider. You’re kind of intrigued and attracted to all that feels unfamiliar. You forget the things that we all have in common. And so I wasn’t really listening very well to him at that point. Whereas now, I don’t think that’s as much an issue. I see much more in common.

Guernica: There’s an indigenous journalist up in Canada, at the CBC, named Duncan McHugh. He’s created resources for journalists who cover indigenous communities. And he talks about the idea of being a “story teller,” not a “story taker.” Does that distinction resonate with you?

Kotlowitz: I’m writing about people, especially in this book, who are private individuals—with the exception of one chapter on [politicians] Bobby Rush and Mark Kirk—who have no obligation to talk to me. I am there completely at their invitation. And I recognize what a privilege it is. I think the way to honor that is to be as open and as straight and as fair and as decent with people as you know how. With each of the stories in this book, once I was done, I went back and read a couple to people, and others I just went back through and made sure I had everything right, made sure there wasn’t anything that would potentially compromise anybody.

Guernica: One of the things that really struck me early on in the book was when you introduced “complex loss” as a term that social workers use instead of “post-traumatic stress.” Can you talk about what that term means?

Kotlowitz: [Social worker] Katherine Bocanegra was the one who talked to me about it. I think what she’s talking about is—you hear this glib comparison, often, between the communities that I write about and war zones. And they’re not war zones. First of all, what happens in war is often considerably nastier and uglier than what we see here. But what’s more is: For people at war, there’s a sense that, at some point, the war is going to end. And secondly, there’s a sense of community, in this odd sort of way, because we’re all in this together. And that’s not the case in these communities.

And so I think to label this kind of trauma as post-traumatic stress disorder is perhaps a little dangerous, because there’s nothing “post” about it. You witness a shooting one day, and it’s not as if, next week or the week after, you go home and put that physical distance between you. You’ve got to deal with it day in and day out.

Guernica: I found that idea really helpful, even just in processing the experiences I had in the classroom. There was a stretch of time in the fall of 2016 where it seemed that every single Monday, at least one of my students came in and said they had a friend or relative who had been shot over the weekend. Like you said, there was nothing “post” about it. They were going back to the scene of that crime every time they went home.

Kotlowitz: And on top of that, they may talk about it on that Monday, but that’s it. Then it’s just kind of completely internalized. And they’re asked to go on as if somehow that moment—the loss of a friend, the loss a family member, witnessing a shooting—is somehow not going to, in part, shape who they are. That stuff doesn’t go away. It just doesn’t go away.

Guernica: When I was teaching in Cabrini-Green, a university social work team had partnered with us. They dropped off three or four blank template forms that you could fill out if you wanted to refer one of your students for services because of behavioral issues or traumas they might be experiencing. And I just looked at them. I had 24 kids in my class, and I felt like I needed 24 of those forms. This idea, “if you have someone in your class who’s struggling” completely misses the point of what’s actually happening.

Kotlowitz: We’ve completely underestimated the impact of the violence on the lives of the people in these communities.

Guernica: I’m interested in your point of view on that violence, as a journalist who goes into these communities day after day. You’ve talked about how when you were reporting There Are No Children Here, you started experiencing a heightened state of arousal and stress that gave you a small window into the emotional reality of that life. You’ve continued to do that kind of work. And there are so many people—not just journalists but also teachers, all kinds of other professionals—who may not live in these communities but experience that secondary trauma regularly, and often by choice. What have you learned about coping, or about self-care? Or what advice do you have for people who are experiencing that?

Kotlowitz: You like to think you’re keenly aware of, not only what’s going on with the people you’re writing about, but what’s going on with yourself. But there was a point, working on the book, where I got really depressed. It was this deep melancholia, this stretch of weeks where nothing gave me any joy, where I found it hard to so much as smile. I’d never experienced something like that before, and I have no doubt that for many in the book, it’s familiar terrain. The aftermath. It wasn’t until I pulled out of it that I was able to look back and realize that there was this secondary trauma.

One of the things about this book is that people canceled interviews on me all the time. At first you kind of take it personally, like, they must not like me. But I realized I was going to talk to people about what, for many of them, had been the absolute worst moment in their life. And all I was doing was reminding them of that. If I were in their shoes, I think I probably would’ve had the same reaction, which is, you know, not now, Alex, not now.

I have to say this, and I don’t mean this glibly: I have such profound admiration for the people in this book. For their willingness, their capacity, to tell their stories, and to tell them in this incredibly thoughtful manner.

Guernica: I find it really striking that when you were reporting this book, even after all these years of doing work like this, you still felt like you got to this really dark place for a while.

Kotlowitz: I felt like I was just writing about death. But when I finally pulled back, I realized all the love that also existed in all these stories. And I think every story in this book is about somebody who is still standing and pushing on, in some really inspiring ways.

Guernica: You write at the beginning that this is not a book that’s offering a set of prescriptions or solutions. Is it at all exhausting or dispiriting to be this many decades in, and not know what to do?

Kotlowitz: It’s really dispiriting. And sobering. And I will say, in some ways, we do know: we need better housing, we need better schools, we need all the things that people have been saying over and over and over again. And that people kind of roll their eyes at, at this point. For me, the most sobering part is that things in these communities haven’t changed a whole lot over the past 25 years.

I did not want to write a book that was prescriptive, and I did not want to write a book that dealt with policy. My template, in an odd sort of way, was Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried, which doesn’t talk about the politics of the war. It’s all on the ground. He writes that it’s about how it gets in your bones.

There’s a line toward the end of that book which has stayed with me: “But this too is true: stories can save us.” I often wondered if O’Brien was talking to himself as much as he was to his readers: if the act of writing the book—of telling those stories—saved him, kept him sane, kept his head above water, gave purpose to where he’d been and where he was going. I thought about that line a lot, working on An American Summer—how, for most people in the book, as difficult as it was for them to share their stories, it gave them a sense of purpose. Telling them helped make sense of, if not of their own lives, then certainly the world around them. Telling them made each of the storytellers feel less alone.

I know it did that for me. When I was in that deep and dark rut I mentioned, there’s no doubt that part of what “saved” me was putting pen to paper and telling the stories that had gotten in my bones.