By Aleszu Bajak

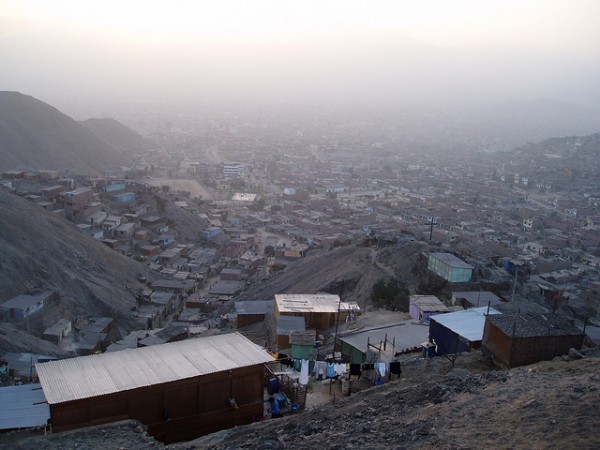

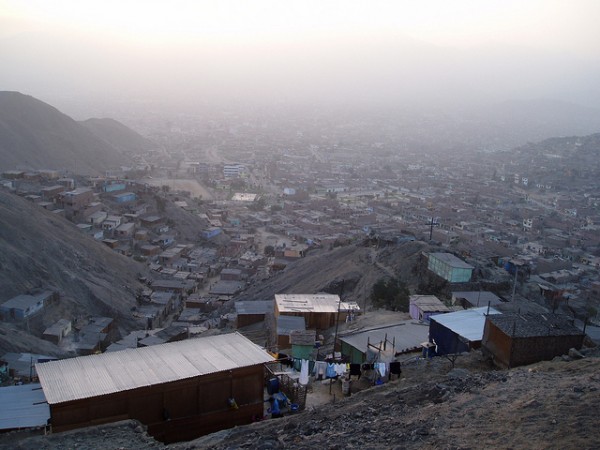

“This is the real Peru,” says eighteen-year-old Frank Rodas as he spreads his arms. He adjusts his baseball hat and looks down into a hazy valley at Villa Maria del Triunfo, a shantytown of sixty-thousand that blankets the hills of southern Lima. “What you see in downtown Lima is all just a screen.”

One hundred and fifty thousand people pour into Lima every year from Peru’s provinces. Like Rodas, most end up in pueblos jóvenes—literally young towns—in improvised dwellings with no running water and sporadic access to electricity. This constant influx means houses are added by the day, built into the rocky hillside with walls of salvaged wood or concrete if the family can afford it. Like Rodas´s parents, most immigrants come to Lima to find work, shelter, and perhaps a way to break out of poverty—they aren’t able to build themselves homemade shelters, except in some of the poorest areas of the country, where they often do so on unstable ground. Paradoxically, many residents of the pueblos jóvenes are forced to pay two to three times more than they would to live in downtown Lima: these settlements are unauthorized and so subject to extortionist landlords who tax access to pirated utilities.

To reach the upper limits of Villa Maria del Triunfo, our taxi crawled up a dirt road past hundreds of these ramshackle houses. Roosters stood guard out front, children played in the street, and the stench from pig pens spread throughout the settlement. Unlike most of the crudely-built houses in Villa Maria, the hogs and their sties are legal on these hillsides; Lima has for a long time zoned some of its marginal districts as agricultural. When the road became too steep for the beat-up station wagon, we got out to walk the last few steps to the highest point, a small neighborhood named Flor de Amancay after the bright yellow flower that blankets these hillsides throughout Lima’s damp winter.

The atrapanieblas stand on the steep hillside above the last row of houses, made of plastic mesh and eucalyptus posts.

With summer quickly approaching, it’s dry and dusty. But the air is crisp and fresh. It feels provincial, alpine. And for ten families living in Flor de Amancay, the location has provided them with a blessing: free water. With the help of local non-profit organizations and community outreach centers, they’ve erected four billboard-sized fogcatchers to harvest water from the fog that rolls into Lima nine months a year. The atrapanieblas stand on the steep hillside above the last row of houses, made of plastic mesh and eucalyptus posts.

Lima’s is a climate where hot coastal air mixes with cool winds off the Pacific to create dense fog. Though this may sound like San Francisco, the city is almost as dry as Cairo. Lima’s annual rainfall barely reaches 11 millimeters and usually falls as a chilly light mist Peruvians call garúa. But in a few hilltop neighborhoods, smart engineering is pulling water out of thick foggy air. Rodas and his neighbors trap close to 600 gallons of water every night between April and December. This means forty-two people in Flor de Amancay can draw water from cisterns filled by the fogcatchers. Though it’s not potable, they use it for washing clothes, to bathe, and to grow zucchini, potatoes, and squash.

To get up close to Flor de Amancay’s fogcatchers, we have to ask for permission. “Since we’ve handed the whole fogcatcher project over to them, we can’t just barge in here anytime we like,” explains Angela Nestarez, a social worker at a community center-cum-clinic-cum-school at the foot of the hill. She found the financing, delivered the materials, and helped train the locals how to build the structures. We knock on the plywood door of one of the community matriarchs. After a moment, a boy in a Barcelona jersey and dirty shorts pulls open the knobless door. “My mother says you can go ahead,” he says and disappears back into the darkness.

The fogcatchers are difficult to make out at first, but I soon spot them on the ridge, standing like towering soccer goals in the mid-morning haze. Their construction is simple: thick green plastic netting six meters wide by four meters tall is stretched between wooden posts that are anchored into the hillside with cement. A plastic gutter runs along the bottom of the net to collect dripping water and send it into a 7,500-gallon concrete holding tank. It can either be stored there—helpful during the fogless summer—or diverted into above-ground cisterns closer to Flor de Amancay’s houses for more immediate use. The entire system, which was helped put in place by Nestarez and her outreach center, is now run by the ten families to whom she handed off the project. They built the fogcatchers and storage and delivery system—with tutelage from visiting engineers—and have free reign over when to use the water they catch and who in their community they can give it to.

Harvesting water from fog is no new concept: desert beetles and tree frogs are known to catch water through a process scientists call fog-basking. It was being studied as early as 1904 in South Africa, in the 1950’s across Chile, and by Peru’s National Meteorological and Hydrology Service in the 1960’s. In the last thirty years, designs to maximize water capture have been researched extensively and non-profits have installed fogcatchers at a cost of $600 to $1000 each in desert regions from Eritrea to Chile.

Today, Lima has more than thirty fogcatchers up and running. But the amount these harvest is trivial compared with what Lima needs. Ten percent of Limeños—almost 1 million—have no running water. Most of these residents live in the city’s squatter communities, home to about one third of Lima’s population. Abel Cruz, founder of the non-profit Peruvians Without Water, has led marches in Lima demanding equal access to water. “But we were protesting for so long about the need for the city to give these people water that we never stopped to think about how we could make our own,” Cruz tells me. So when the German organization Alimón e.V. came to Peru in 2006 with plans for a pilot project to harvest fogwater, he got onboard. Working with Alimón and other NGOs, Cruz helped with pilot studies, calculated optimal orientation and installation specifics, and then trained locals how to build the fogcatchers. He’s installed dozens above Lima’s shantytowns. Cruz recently secured $20,000 in funding from USAID to build twenty fogcatchers, and with more funding he hopes to grow that number to 200. On the taxi ride up to Flor de Amancay, Cruz was giddy as he pointed out tanker trucks and dozens of houses that had been built within the last month, some upon the steepest grading I had ever seen.

Look closely at any of Lima’s pueblos jóvenes and you’ll see them speckled with blue plastic barrels, in front of most houses or out in the road. Look long enough and you’ll probably see a blue tanker truck winding its way up the dirt roads, filling these 50 gallon kegs for one to two dollars a pop, depending on how high up the hillside they are made to drive. In Villa Maria del Triunfo, we saw no fewer than five of these enormous cumbersome trucks navigating the precipitous dirt roads. Often these trucks run out of water before they make it to the higher neighborhoods like Flor de Amancay. These water deliveries are a daily routine for Lima’s impoverished neighborhoods. A family of five—and many are larger than that—will go through at least one 50 gallon keg in a day. With such demand, the delivery service is susceptible to price gouging: trucks from the state utility company SEDAPAL, as well as private companies, reportedly fix prices and sometimes deliver water from questionable sources.

“In the winter, when the roads are all washed out, the trucks don’t make it up here,” explains Berta, a Flor de Amancay resident. Holding onto her restless toddler, she looks up at the fogcatchers. “The atrapanieblas have been helpful but there aren’t enough. We need ten times as many.” The neighborhood is also facing another problem that will affect its access to water. New squatters from the other side of the ridgeline have already cut a wide trail into the hill just above the fogcatchers. Once houses are built along this path, there will be little space to build the forty-five fogcatchers social worker Angela Nestarez plans on adding once she secures more funding.

Ten percent of Limeños—almost 1 million—have no running water. Most of these residents live in the city’s squatter communities, home to about one third of Lima’s population.

The fogcatchers are clearly not a panacea. Lima remains a desert city with water problems that defy a simple solution. Authorities acknowledge that resource availability needs to be improved across social classes, but the state utility company SEDAPAL has been decades slow in building infrastructure in poorer communities, which are constantly expanding. The World Bank has moved to pick up the slack, having pledged $55 million to improve water connections in northern Lima’s poor neighborhoods. When completed, the project should bring water to more than 60,000 homes.

The visible truth is that artificial irrigation beautifies the rich neighborhoods and the poor stay thirsty. SEDAPAL recently estimated that Lima’s citizens each use an average of 251 liters of water per day. To put this in perspective: a five-minute shower can use up to 100 liters of water while washing a car can take up to five hundred. But if poor families of five in Villa Maria are all sharing a 200 liter blue keg of water every day, it’s clear that there are plenty of areas in the city where precious water is being wasted. On top of that, SEDAPAL claims that 35 percent of Lima´s potable water is never paid for or is lost through damaged infrastructure: enough water to supply 2.5 million people a day. One solution the utility has proposed to combat waste is to increase tariffs on water across the city. They argue that paying more for water will force Limeños to understand the value of the precious resource.

Lima’s limited freshwater resources are dwindling: tropical glaciers that feed Lima’s rivers are receding and the city’s water table is falling. With a population of 9 million and growing, water rationing is not a concept that is being taken seriously enough. The city’s water consumption is expected to rise 50 percent by 2040; Limeños will need to soon get used to rationing. The Peruvian government and SEDAPAL have scrambled to develop answers and claim they will invest $2 billion to build more dams and reservoirs in the Andes far from Lima. This may bolster water resources upstream—though likely also bring unforeseen changes to those communities—but without limiting overuse, Peru’s capital will dry out.

Despite the difficulties he faces in his small neighborhood of Flor de Amancay, Frank Rodas is genuinely hopeful. He’s an optimistic teenager, proud of the place that’s been home for the last four years since moving from Cajamarca, a provincial city 800 kilometers away. The training he’s received from NGO engineers on building the fogcatchers has made Rodas ambitious—he has big plans for Flor de Amancay. “I want this to be green year-round,” he says, gesturing up towards the ridgeline. “If we get enough fogcatchers up here, these hills would look great. They could even be a tourist attraction.”

Mine is an abiding relationship with Lima. My mother was born here and I’ve been to the city many times. But the chasm between rich and poor has never been so clear as during our visit to Flor de Amancay. I thought of the manicured lawns of Miraflores that teem with bright flowers and palm trees, with their legions of landscapers and conspicuous irrigation. Confronting water scarcity in Lima will mean addressing this gap. And soon.

Aleszu Bajak is a science writer currently living in Peru. He is founder of LatinAmericanScience.org, a weekly digest of science news out of the region.