A

writer’s currency is his imagination; stories are his wares. Bartering with an author is a journey through the abstract, so it’s not surprising that what a reader holds onto are concepts, not objects: the author’s style and voice; themes and morals; arguments and epiphanies.

But what about the elements of a writer that give him and his writing a sense of physicality? The hand that held the pen. The cigarette that burned through the paper. The coffee that dripped punctuation points in between the words. The wrist that was encircled by an ID bracelet. The fingers that stroked and petted a panting black poodle, before molding him on paper into an innocuous white sheep?

This is how the Morgan Library leads a visitor through its exhibit “The Little Prince: A New York Story”, running through April 27th. A small glass case at the exhibit entrance displays the silver identity bracelet that author and pilot Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wore on the flight on July 31, 1944 that would be his last—he was never seen after that day. Exhibit curator Christine Nelson told the story of the bracelet’s discovery to a crowd of press, literati, and devotees of Saint-Exupéry with a smile on her face: forty years after the garrulous aviator disappeared, his bracelet was snagged in a fisherman’s net, and sent to the address embossed on it: Saint-Exupéry’s publishers in NYC. “He died wearing a tangible reminder of his link to this place,” Nelson said.

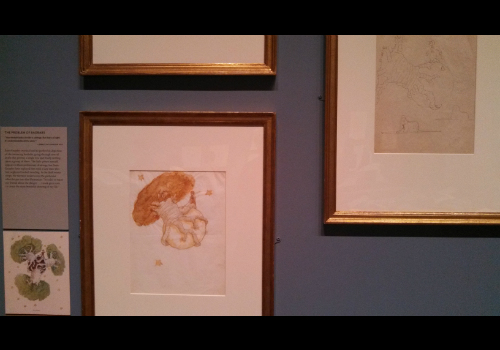

The exhibit traffics in visual cues: multiple versions of the same illustration, doodles, and crushed up pages converge into the version of the immortal little prince that readers know like the back of their hand.

How striking, the word ‘tangible.’ This small metallic souvenir reveals a solidity about Saint-Exupéry—a wrist, a hand, cigarette-stained fingers—that no words could convey with such immediacy.

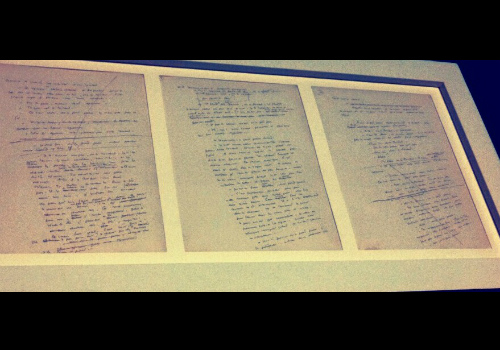

But the exhibit traffics in visual cues: multiple versions of the same illustration, doodles, and crushed up pages converge into the version of the immortal little prince that readers know like the back of their hand. Faded, dog-eared pages are carefully framed and installed on the walls—creativity that has been time-stamped—but the coffee stains, cigarette burns and repeated cross-outs on these same manuscripts remind us of Saint-Exupéry’s continuous work on a single sentence, or scene, and the many cups of coffee and cigarettes they required. Saint-Exupéry attempted fourteen other versions before settling on the final version of the fox’s now-famous line. The exhibit lists them all, alongside a manuscript covered in scratched out sentences:

| Mais ce qui compte est invisible. | But what matters is invisible. |

| Ce qui compte est toujours invisible. | What matters is always invisible. |

| Mais l’essentiel est toujours invisible. | But what is essential is always invisible. |

| Ce qui est important est toujours invisible. | What is important is always invisible. |

| Le plus important demeure invisible. | What is most important remains invisible. |

| Le plus important est invisible. | What is most important is invisible. |

| Ce qui est important ça ne se voit pas. | What is important cannot be seen. |

| Ce qui compte ne se voit pas. | What matters cannot be seen. |

| Ce qui est important ne se voit pas. | What is important cannot be seen. |

| Ce qui est tellement joli n’est pas pour les yeux. | Something that lovely is not for the eyes. |

| Ce qui est important, ça ne se voit pas. | What is important, that cannot be seen. |

| Ce qui se voit ça ne compte pas. | What can be seen does not matter. |

| L’important est toujours ailleurs. | What is important is always somewhere else. |

| Ce qui est le plus important c’est ce qui ne se voit pas. | What is most important is that which cannot be seen. |

One gets a sense of Saint-Exupéry’s painstaking process—not just a mental exercise, but a physical one. Credit additionally goes to Nelson and her team, including biographer Stacy Schiff, who had to decipher Saint-Exupéry’s handwriting, which was not only near-illegible but danced, sloped and tilted across the page like a teetering plane. “One of the tricks of a good biography,” Schiff confessed at a follow-up conversation at the Morgan Library, “is to pick a subject whose handwriting you can actually read.”

Schiff, who wrote Saint-Exupéry: A Biography in 2006, also said of Saint-Exupéry’s hybrid professions: “One thing you want in a pilot is a perfectionist; one thing you don’t want in a writer is a perfectionist. Saint-Exupéry had it reversed.” Saint-Exupéry rejoiced in how primitive—he might say fundamental—flying was in the 1920s, but others regarded his frequent crash landings with expected alarm. She recalls interviewing American pilots who had flown with Saint-Exupéry in 1944 (the last remaining peers of Saint-Exupéry still alive today) who knew nothing of the man’s extensive and prize-winning literary career for books like Southern Mail (1929), Night Flight (1931), Wind, Sand and Stars (1939)—ruminations on aviation, loneliness, and life—let alone The Little Prince (1943). Sitting next to him at altitudes of 5,000 feet, they instead wondered, “Who was this Frenchman who couldn’t speak the language, couldn’t fly a plane, and did card tricks?”

“As close as this exhibit brings us to the moment of creation…this is but a glimpse of the creative process.”

In his “notoriously chaotic style,” to quote Nelson, Saint-Exupéry’s hands were always moving: steering the most primitive of aircrafts eighteen hours across the Atlantic, crash landing in the Sahara so often it could be called ‘regular,’ scribbling sentences and then scribbling over them, lighting cigarettes, shuffling card decks, and pointing and gesturing non-stop when he narrated stories that occupied entire dinner parties and boat rides. The walls of the exhibit are covered in his world-famous illustrations from The Little Prince: the narrator’s elephant-inside-a-boa; the little prince standing on his planet; the 43 sunsets he watches one evening from his chair because “You can see the day end and the twilight falling whenever you like.” These evoke a surround-sound—or surround-sight—universe, what Saint-Exupéry saw and envisioned when he was flying through the dead of night, or when he lived in the silent vastness of the Sahara as a young man.

But, Nelson cautioned us, “As close as this exhibit brings us to the moment of creation…this is but a glimpse of the creative process.” Similarly, Saint-Exupéry’s countless metaphors in his various books are oblique approaches to the very physical, hands-on act of flying a plane. Before the machines became overly mechanized—reducing pilots to button-pushing accountants, Saint-Exupéry complained—the steadiness of the plane was provided by the pilot’s grip. Howard Scherry, president and founder of Remembering Saint-Exupéry, notes the attention the author gives to hands in various disparate writings. In Southern Mail, the pilot is a “scaphandrier hors de ses elements,” a deep-sea diver outside his element. “The pilot who goes up is the soulmate of the deep sea diver who goes down,” Scherry says. In Night Flight, “the pilot who flies into the darkness of the night with only his lamp…is the same as the miner who only has his lamp, who goes into the dark, and with his strong shoulders, has to throw away the unknown. It’s incredible. Deep sea diver; pilot; miner.”

Divers and miners, swimming and digging, working with their hands: the most essential part of a pilot and, as this exhibit quietly reminds us, of a writer.

Saint-Exupéry worked on The Little Prince in his dear friend Silvia Hamilton’s Park Avenue apartment, finding inspiration in her broken French, pet poodle, and even a doll as model for the little prince. Trying his hand at illustration for the first time, he doodled relentlessly until satisfied. He gifted his sunset sketch, today an instantly recognizable image, to Silvia’s grandson Mark. Nelson deliberately showcased that drawing, which sits in roughly the center of the story, in the center of the exhibit. The little prince’s youth and innocence is a source of much analysis by writers, philosophers and students today. The Little Prince’s dedication reads:

Nelson rejects the question of The Little Prince as a children’s book versus an adult book by answering, simply, that it is a book. She delights in the “wonderful conspiracy between the narrator and children: the narrator is an adult, he’s remembering the imagination as a child and how that was crushed out of him by adults. I think young readers can identify with that.” Saint-Exupery reminds readers that “their childhood is always contained within them,” as well as the converse, that children can comprehend loneliness and sadness, and other “adult” tendencies.

Was reality what existed on land, or in the air? Was it visible to the eye? Saint-Exupéry took on this question as a man of god, a seer, a saint, might.

A display case opposite the ID bracelet contains a review of The Little Prince by P. L. Travers, the Australian-British novelist who wrote Mary Poppins. This children’s author is attentive to the same question, and writes:

Nelson noticed similarities between The Little Prince and Saint-Exupéry’s earlier works, which brought him acclaim well before the story of a boy from asteroid B-612. The exhibit includes quotation pairings that demonstrate Nelson’s theory that Saint-Exupéry is “retelling the same story over and over in different genres. The Little Prince is fiction, but it has qualities of memoir as well.”

Spending so many hours navigating a small vehicle through the skies, above oceans, in between mountain peaks, and dodging bullets, Saint-Exupéry toyed with the idea of existence and perception as well: was reality what existed on land, or in the air? Was it visible to the eye? Saint-Exupéry took on this question as a man of god, a seer, a saint, might. He echoes the sentiment of the fox in his own voice, to a dear friend, as he writes in Letter to a Hostage: “A childhood home [remains] alive in the memory. A friend we know nothing about, except that he exists.”

In The Little Prince, the little prince was a friend to his narrator, but the narrator knows little about him. When he disappears, it’s not clear how he died, or where he has gone. Saint-Exupéry’s disappearance in 1944 is uncannily similar. Seventy-one years since the book, seventy years since Saint-Exupéry’s death, this exhibit guides the eyes—and hands—of the curious through a life of handiwork of one of the most gifted authors and philosophers to have put pen to paper, guided plane to sky, carried a little prince in his arms and placed a cigarette in his mouth.