By Aditi Sriram

Debut author Rohini Mohan first visited Sri Lanka in 2009 as a master’s student studying political journalism. What began as a thesis project grew into 400-page account of three central characters who, as Mohan puts it, are “as old as the war.” Their lives are part of the fabric of Sri Lanka’s turmoil, their memories the country’s battle scars, their words the official record. The Civil War ended in 2009, but these characters live on, struggling to digest what they endured and identify what they are nostalgic for.

The more time Mohan spent in Sri Lanka, the more unanswered questions she had about how the war echoed through the country’s politics, even after five years of peacetime. So she “kept going back,” and gaining access to people not just in the capital city of Colombo, but also rural villages and the jungle land in the north called the Vanni. Using a network of activists, locals, and journalists, Mohan wormed her way into each community and identified ten main characters with which to anchor her book. A fluent Tamil speaker, she did not require an interpreter, which put her subjects at ease—but that did not mean she understood everything they said. Her characters spoke a Tamil rich in euphemisms for violence and a crudeness about weapons, which Mohan painstakingly deciphered after the fact. Such language situated her characters, and also gave voice to the now defunct separatist faction, the Liberation of Tamil Tigers Eelam (LTTE). When her characters referred to “martyrs,” it reflected how the LTTE elevated any death to the greatest sacrifice. When they described their AK-47s, Mohan pictured the LTTE’s unforgiving training camps.

The Seasons of Trouble: Life Amid the Ruins of Sri Lanka’s Civil War follows two women, Mugil and Indra, and Indra’s son Sarva, who took a few years and several interviews to trust Mohan with their stories. This is her first interview about the book with Guernica, which she did over Skype from India. Read it in conjunction with an excerpt from the book in our Features section, about Mugil, who joined the Tamil Tigers when she was just thirteen years old.

—Aditi Sriram for Guernica

Guernica: Seasons of Trouble is not the first book about the Sri Lankan Civil War, nor will it be the last. How is your book different from the others?

Rohini Mohan: At every stage, I tried to bring a lot of interiority into every narrative. I wanted to get into details about how my characters thought about their children, what they ate, the kind of routine they had in the day; things that make people full. That’s why we care about some people while others seem like survivors or victims in a faraway country. My book makes them fuller.

Almost every female combatant that I spoke to said, “I am nothing less than a man.”

Seasons of Trouble is similar to others in that they’re all searching for the answer to how people in a post-war country live, and what it really means to come out of such a long conflict. But until now the only book that has come close to getting the nuance and complexity of the place and the conflict itself is Only Man is Vile, which was written by William McGowan, an American journalist, in the ’90s. He writes in that very traditional format of the journalist in the story—in first person, as well—taking the reader through his confusions, his bewilderment, his chasing of suicide bombers. It’s very exciting but, I felt, a very masculine narrative. War non-fiction is usually like that, and I wanted to hear more women’s voices; two of my characters are women.

Guernica: The women in the book, especially Mugil, appear strong and unintimidated. Was feminism a part of their philosophy, or was that overshadowed by a greater sense of activism and radicalization?

Rohini Mohan: Feminism was absolutely present. The LTTE used motivational feministic speeches to attract women to join them. Sri Lankan Tamil society is extremely patriarchal, and while women are strong members of the family and of the community, they are definitely walled in by a lot of expectation, family, roles, and other usual tropes that conservative patriarchal societies impose upon women. They place their family first, they dress a certain way, they cannot challenge the men. So when the youth was becoming so radicalized, when LTTE and other radical groups were being set up, feminism was used to both uplift women and also recruit them for the LTTE. Mugil and I had a lot of conversations about this: almost every female combatant that I spoke to said, “I am nothing less than a man.” Every single one of them said this to me.

Joining the LTTE was their way of getting freedom: they could wear pants, they watched movies, they read a lot. Everything was consumed by militancy, as was feminism, and that friction is seen now as ex-female combatants struggle to fit into the community again, after rehabilitation. Women who worked in some capacity with the LTTE—not necessarily combatants—are looked at as not feminine enough in the community today.

Guernica: The excerpt we featured paints Mugil to be not only fearless, but cold. She wakes up after hiding out in a tree all night, and sees the five girls in her charge strewn below her, raped and dead. You write, “Mugil swung down from the tree, looked at her compass, and walked away.”

Rohini Mohan: That was one scene that I was very nervous writing about. She said this to me in absolute clarity, and just once. It was the first time I had a proper interview with her. This was in 2010, and since then, she has not wanted to talk about it. She said, “I’ll tell you; don’t ask me again.”

They never used the Tamil words for raped, “kaṟpaḻittār.” Instead, they would say, “they ruined her.” It was too harsh to say the other thing.

In later years, as there was more and more oppression from the army and the government, a lot of people who were questioning the LTTE itself, like Mugil, started feeling nostalgic about their commitment to the LTTE as a time when they were free. Situations that would criticize the LTTE she did not want to talk as openly about, because she was feeling differently now.

This was a big advantage I had; it was completely lucky. I could have not known this kind of change in mindset if I had met her for the first time in 2011. It was only because I met her in 2009, and again in early 2010, that I was able to find out this incident even happened.

Guernica: And your fluency in Tamil helped put Mugil and the others at ease?

Rohini Mohan: It was very hard at the beginning. I interviewed close to ten people properly; each spoke different kinds of Tamil. If they were from tea plantations, they would have a different Tamil. If they had any exposure to Colombo or cities, their Tamil would be different. Those in the Vanni had an extremely lyrical, entirely Tamil vocabulary. They did not use a single word of English, and were not used to understanding my Tamil.

I could say “human rights” to someone in Colombo, and they would understand. To Mugil, I would have to say “maṉita urimai”—and that’s one of the simpler words. She didn’t use the word “chocolate.” In India, a common substitute for “chocolate” is “Cadburys.” In Sri Lanka, the brand name equivalent is “Kandos,” but there is no “k” in Tamil, so they would say “gandos,” which I didn’t understand at all. There was a scene in which Mugil saw a child eating “gandos” outside a hospital, and I had no idea what she was talking about.

They never used the Tamil words for raped, “kaṟpaḻittār.” Instead, they would say, “they ruined her.” That is shyness, not a lack of words in the Tamil language. It was too harsh to say the other thing.

Anybody living in the Vanni or who was connected to the LTTE would use the word “martyred” for those who died—even civilians. It’s how militants increased the number of people joining the LTTE, by making all deaths into martyrs. Similarly, the word “koththu kuntu,” which means cluster bomb, was thrown around a lot, and used to refer to any kind of bomb. If people used it in an interview, I learned to ask them to describe it so I could confirm whether or not it was that specific kind of weapon that they were referring to.

Guernica: In the preface to the book, you describe being “privy to incidents and emotions [Mugil et al] subsequently and frequently blocked out, reframed or remembered differently.” Did this affect your own research as well?

Rohini Mohan: I made notes of my notes because I was constantly afraid of forgetting something or misremembering something. I think it’s a good fear to have, but it’s also paralyzing.

Mugil’s brother kept a diary in detention; it even included diagrams. What he had written was so powerful. I call it literature.

When I wrote the first few chapters, Mugil had three different wounds on her body, each sustained at different times during the war. I mixed them up! It was only during the editing process that my wonderful editor and proofreader found that the wound was moving—the injuries were moving from place to place on her body because I misremembered the details. So I called Mugil back and we checked. She was so annoyed with me, but she helped anyway.

Guernica: Moving wounds! Did Mugil or the others keep records of their time in the war?

Rohini Mohan: Mugil’s brother kept a diary in detention; it even included diagrams. What he had written was so powerful. I call it literature because he uses the same tropes that I find in fiction: the way he writes a scene, he describes what he’s feeling, the other person’s clothes, what it smells like, how angry he was, or wondering what the other guy must be thinking. He had written it for someone else to read; it wasn’t a personal diary in that sense. These records are their way of holding onto something that they only have their memory now.

Guernica: How did you come up with the title?

Rohini Mohan: Initially I had other options, for example, “Unfinished War,” inspired by the science-fiction book The Forever War, which is my favorite anti-war book. But these titles felt like war books, and I don’t read war books. I read about people who live through things. I don’t want to know how many bullets were fired; that doesn’t interest me. Maybe it should, because I’ve written about conflict, and I will include it in a book because it’s important, but it doesn’t move me.

In Mugil’s section, I have a sentence of how her impression of her own life kept changing according to the season of troubles. A lot of people that I interviewed didn’t use the Tamil words for war or battle, but they said “prachanai kaalam,” meaning the time of troubles or problems. That stuck, and my editor Leo Hollis at Verso turned that into the title.

Guernica: Is the season of troubles over for Sri Lanka?

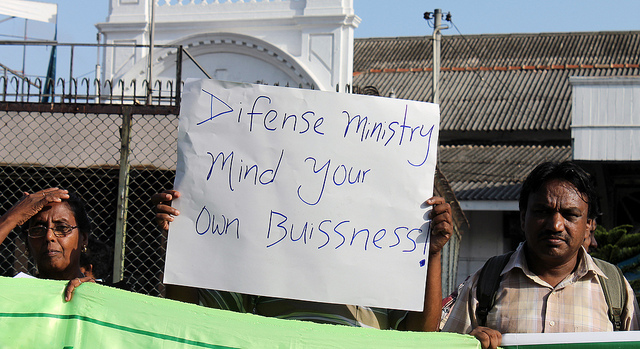

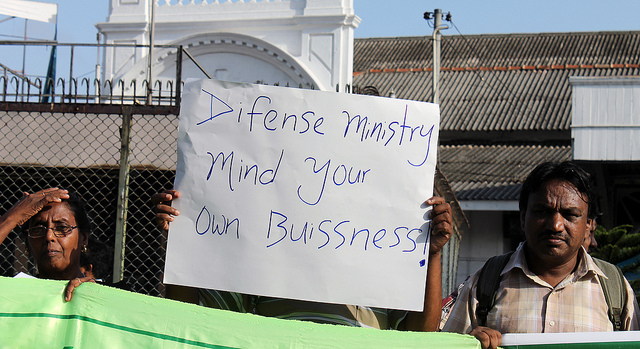

Rohini Mohan: Even though I focus just on the Tamil community in my book, I began to sense the increasing triumphalism seeping through the Sri Lankan government since the war ended five years ago.

Many people worry that the current political climate could give rise to a Tamil militancy again, and that is what I’m asked all the time. No one can answer that, but I do not believe that it can happen; Tamil people are too broken and militancy has been actually, completely rooted out. So that’s not the future—but rather, another kind of war against another minority, which is the Muslims.

The last scene in the book is set in Colombo. Mugil’s husband has just returned from visiting Mugil (who has been detained by the Terrorist Investigation Department in Colombo), and he sees Muslims being attacked by monks and other Sinhalese on the streets. I didn’t address the Muslim issue in my book much—it lived in conversations through the book—but in this scene I realized that all of this ethnic war has polarized communities so much that the country will see a repeat of what happened in the ’80s against the Tamils. Only now it will be against Muslims.

Rohini Mohan is a political journalist based in Bangalore, India. She has won prestigious recognition for her work, including the Charles Wallace Fellowship 2013; the ICRC Humanitarian Reporting Award 2012, New Delhi; the Sanskriti–Prabha Dutt Fellowship 2012, New Delhi; and the South Asian Journalists Association award 2011, New York. She has written for Tehelka, The Caravan, Outlook, The Hindu, and the New York Times. Her website is http://www.rohinimohan.in/.

An excerpt from her book The Seasons of Trouble: Life Amid the Ruins of Sri Lanka’s Civil War can be read in our Features section.

Aditi Sriram teaches College Writing at SUNY Purchase and writes for various magazines including Narratively, Outlook Traveller, and Fountain Ink. You can read more of her work on her website www.aditisriram.com.