Michael Gac Levin

0

I was accepted to the Vermont Studio Center in a stagnant October. I couldn’t remember applying and I only agreed to attend because I’d been staring at the blank expanse under the title of my new novel for weeks. Once I became preoccupied with residency logistics, I started figuring out the novel’s plot. Or maybe that’s too voluntary. Ideas, lost in the post-MFA haze, evaporated in the assembly line rhythm of New York, began popping all around.

1

The train to Johnson, Vermont suffered difficulties, and I had to transfer to a bus (the unique horror of the unexpected bus), and then a second train. Each leg exposed me to more commuters, and I began working up theories about who else was going to be a resident. A European woman ordered a vegan burger and laughed nonsensically in the café car: artist. A man walked into the bus bathroom cradling a rolled poster tube like a newborn: artist. An older man in a knit hat glanced my way, then jolted when we made eye-contact: writer. “I’m about to know these people,” I thought while dropping ice cubes from a paper cup into my scalding coffee. I could feel them analyzing me too, with the only identifier that would matter for the next month: in Vermont, I was a writer. It was the simplest sort of validation, and one I’d apparently been craving. As darkness fell, I wrote the first seven pages of my novel. After months of agent letters, doubt, publisher letters, self-flagellation, television work, pitches for valedictory experiential first-person essays—after four months that contained no tangible writing—I started working.

After months of agent letters, doubt, publisher letters, self-flagellation, television work, pitches for valedictory experiential first-person essays—after four months that contained no tangible writing—I started working.

2

We arrived in Johnson past midnight. There was the kind of cold that makes metal feel fragile, and it was quite dark, and we forlorn train people gathered in the residency’s kitchen area to eat untoasted bread. I knew that everything—the jam varietals, the train people, the mere fact of my existence in Vermont—would settle into normalcy, but that night my observations were slow and precise. I’ve read that childhood takes so long because we feel time more intensely when processing the new—the first time we see, let’s say, a goose, we engage with it on an inquisitive level, but every goose afterward is partially elided. As we age, our brains skip more; life loses those improvisational digressions; each goose commands less and less of our attention. Thus, the seemingly banal thing people always say about time speeding up. In Vermont there were a lot of geese.

3

Harriotte Hurie, in her sixties, was in Vermont on a fellowship for blind writers, working on a memoir of her travels through India, where she’d been a musical anthropologist. Speech-to-text software had advanced to the point that she finally felt comfortable reviewing her own writing. She was a skillful mimic and deeply inquisitive—she immediately gleaned from vagaries of accent that the laughy woman who’d ordered the veggie burger on the train was Croatian. Harriotte’s partner was with her on the first day, leading her around the campus and the town so she could map it out mentally—seventy steps to the laundromat; twenty five to the coffee shop. He was at least a couple of decades younger than Harriotte, the kind of boyfriend who understands that he’s dating the star of the show and enjoys his supporting role. At her nudging, he told me how they’d met. Harriotte had taken to playing the recorder on the Boston T and he’d gotten on one day and heard her. Intoxicated, he drew nearer, sat next to this white-haired, white-eyed woman, and listened silently for a while. Then, he reached into his jacket pocket and pulled out his own recorder. They played in duet until Harriotte reached her stop. The man, though he was nowhere close to home, joined her.

Marisa Finos

Performance

Clay, Sound.

63” L, 50” W, 45” H.

2015

4

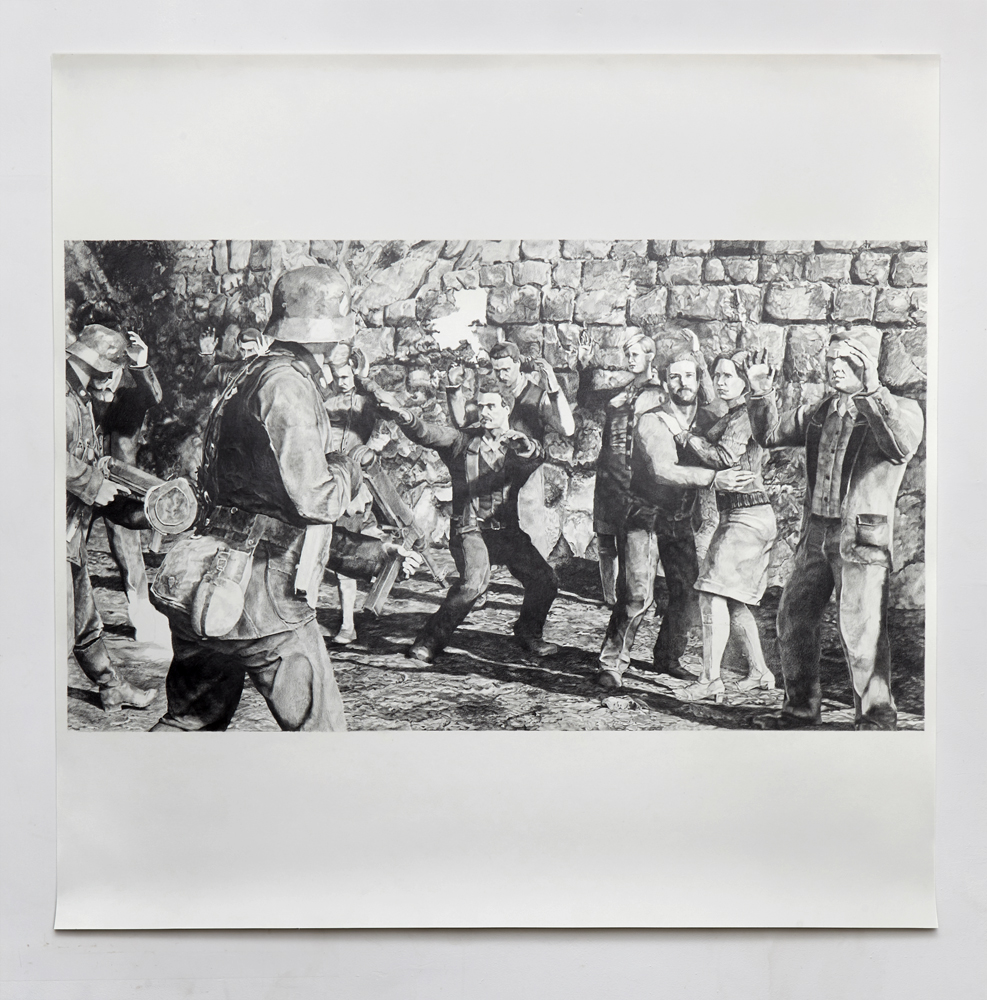

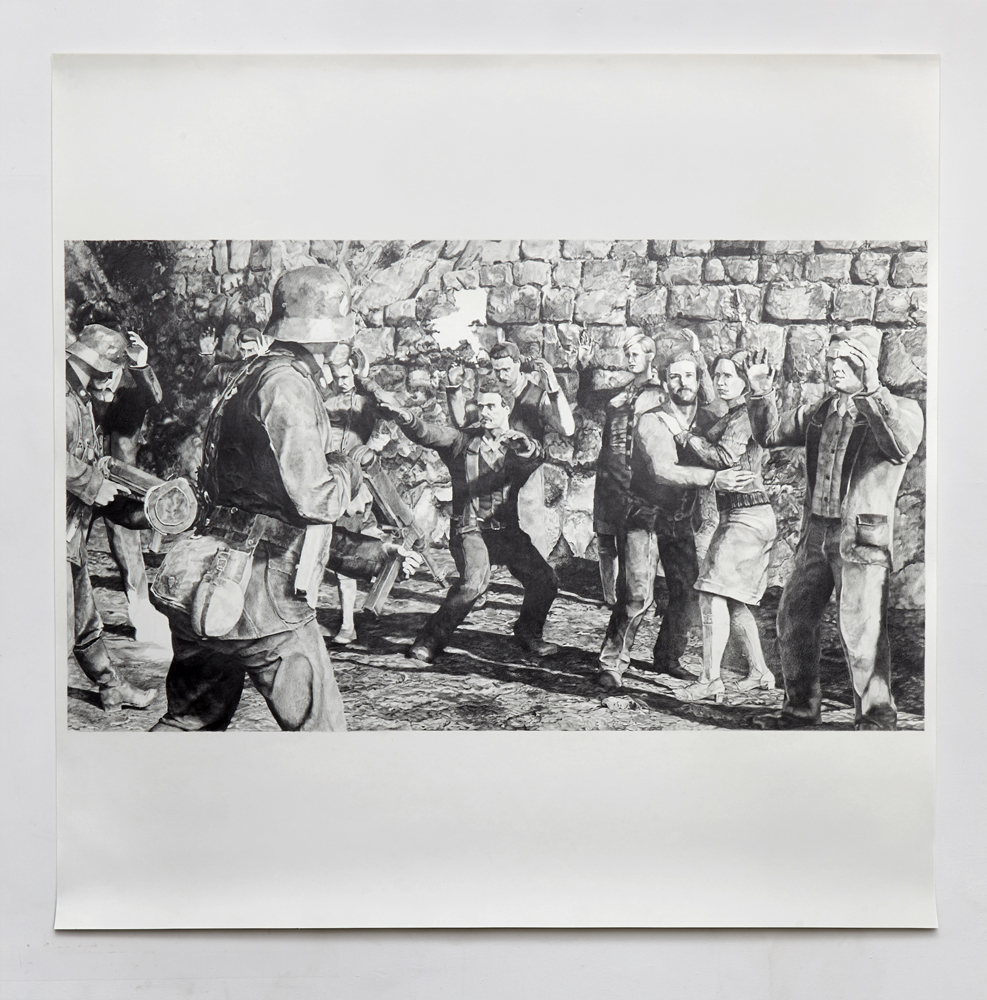

The Vermont Studio Center is at its core a residency for artists. The founders emeritus, who take turns wandering the grounds like Banquo’s ghost, are themselves painters. There are forty visual artists and only twelve writers in attendance. This is ideal. One of the main appeals of the writing MFA is exposure to the collective mania that comes prepackaged with a vocational program whose aspirations loosely correspond with reality. But MFAs, much as I loved mine, have developed a disorienting inclination towards the market. And New York, though it thrums with paint-stained artists, offers little opportunity to actually engage with them. In Vermont, we had painters, sculptors, photographers, and performance artists. They danced in front of their canvases and talked while molding their clay; every physical gesture bringing their work closer to completion. Their slide lectures were one of my favorite things there. I liked the drawings of Michael Levin, whose work engages with failure of depiction. Most notable, to me, was Michael’s photo-realistic drawing of Nazis raiding the Warsaw ghetto. When you get close enough, you realize it’s too perfect: the faces are identical; it’s a still from a videogame rendered in pencil. I loved the idea of a harrowing subject matter becoming so market-driven that it’s lost its emotion. By the end of Michael’s lecture, I decided the protagonist of my novel would be an artist.

5

I’ll confess that I signed up to write this essay before I attended the VSC, and I did that to push me outside of myself. Writing can have the unfortunate side-effect of encouraging isolation, which leads to an absence of material. One keeps begging off from going to parties because one has to write a party scene. “But,” I said to myself habitually at VSC while contemplating things I didn’t really want to do, “Guernica!” So I attended a talk on meditation. It focused on letting go of the need to identify or classify things—not overly helpful for someone who deals in simile—and some basic breathing techniques. I was ready to write the whole thing off, but then the lecturer (the male founder emeritus, whom I’d acquired a dislike for after he threw a dinner roll at my head for sneaking a peek at my cell phone two nights earlier) paraphrased Phillip Guston: “When you’re in the studio painting, there are a lot of people in there with you—your teachers, friends, painters from history, critics, and one by one, if you’re really painting, they walk out. And if you’re really painting, you walk out.”

6

By the end of my first week, recalibrated time began to speed up again—but things had become disturbingly Pavolvian. I’d subconsciously penetrated the opaque rubric of the meal program and woke up earlier on bacon days. When the salad bar’s vinaigrette’s formula was tweaked it took me a week to recover. My sundry New York issues didn’t seem as important as, say, karaoke, that great Saturday night unifier. And no karaoke night was more crucial than the first in Vermont, which fell on Halloween. Thus: scaraoke. There were innumerable renditions of “Thriller,” a couple of “Monster Mashes,” and flush with the temporary extroversion of the residency, I performed J-Kwon’s “Tipsy.” In the manner of all triumphant karaoke occasions, part of me is still on that stage. Afterward, I staggered through a graveyard at some unearthly hour, drunk—I never drink—reading the century-old tombstones. My favorite said SAMPLE, and I yelled for everyone to come see it. Self consciousness, so much a part of my life, so much the enemy when it came to the new novel, had temporarily vanished.

7

My studio was on the second floor of the writer’s building, facing a surprisingly dynamic river. The walls were so thin that I couldn’t talk on my phone or play music or cough without needing to apologize, and the internet was so crummy that I couldn’t watch YouTube. The only sound most of the day was Harriotte playing her recorder. My bedroom, though something out of an imagined hellish ‘70s motel, at least shared a building with an excellent small library, where I spent a lot of time with my taxonomy of cheese notebook. The gym was a 1.5 mile run away and couldn’t make change for my $50 bill on the first day, so I passive-aggressively ran to the doors and back for the rest of the month. Meals were communal times, and though it did revive the repressed “who should I sit with” cafeteria issue that afflicts the mid-range popular, at least there was only one dinner option a night. The absence of decisions made it easier to work. In the imposed rhythm of the day, there wasn’t the time to step back and appraise my ideas, to delete paragraphs, to question my identity. Whether or not I was a writer was temporarily immaterial, because I was writing.

In the imposed rhythm of the day, there wasn’t the time to step back and appraise my ideas, to delete paragraphs, to question my identity. Whether or not I was a writer was temporarily immaterial, because I was writing.

8

I knew my lead character was an artist, but I needed to figure out what kind. A lot of my novel was turning out to be about self-destruction, and my experience with French antiques (that’s a whole other experiential first-person essay) gave me a head start in understanding bronze making. With that in mind, I paid a visit to Duncan Lewis, a naturalist sculptor who gave me a tremendous lecture on the lost wax technique. Duncan, an enthusiastic North Carolinian in his fifties, is, as far as I can tell, permanently clad in a stiff, serial killer apron and thick gloves that extend halfway up his forearms. Over the course of an hour, it emerged that the lost wax technique works much like the first half of the casting scene in Andrei Rublev. A model in clay is made, and then the artist makes several copies, or negatives, of the model, each of which will eventually be destroyed (that’s the lost wax). While the bronze heats in a vat, the artist constructs thin wax tubes feeding in and out of the negatives. The tubes work like a cardiovascular system, allowing the molten bronze to course through the piece and fill the mold. These tubes are called sprues. After the bronze is poured into the mold and all the wax melts and leaks out to the ground, you’re left with the statue and its bronze sprues. An artist must knock off dozens of sprues with tiny hammers before the work is done. The technique is prone to the MFA graduate’s tendency to get overly post-modern, to embellish the process of creation. Perfect for my failed artist.

9

Years ago, my mom bought me a copy of MFA vs NYC, which was promptly exiled to my self-help shelf alongside a much-leafed jump shot instruction manual from high school. I’ve wandered New York the last two weeks with the volume in hand. Since I have an MFA and have lived in New York for 13/15ths of my life, it was a bit embarrassing: all those encouraging glances, a couple of attempts at unsolicited advice. I realized that there was something to my Vermont experience that Harbach was searching for. He says of New York writers: “They partake of a social world defined by the selection (by agents), evaluation (by editors), purchase (by publishers), production, publication, publicization, and second evaluation (by reviewers) and purchase (by readers) of NYC novels,” and this is true, but in Vermont, there was a resident writing a non-fiction book about a 19th-century woman who accompanied her whaler husband on extended voyages. There were writers who’d written half a dozen novels, never sent any out, and were simply there to write another one. We would read Proust out loud to each other after dinner and didn’t feel that weird about it. I realized that my perception of my writing had come to be defined by the industry, that I needed to get back to my original, forgotten ambition to simply make art.

10

I saw decades worth of twelve-foot-high puppets lumped in a massive barn. It was fifty degrees in the barn, kept cold to discourage the rats, and I simply wandered in, unchecked. The puppets were political, anti-government, anti-commerce, horrible Jesuses and cheerful Satans and crooked police officers, packing every inch of the massive building. They’d featured in shows that have been scaring Vermont children all the way back to 1960. It was obsessive work. I stared at the mâché for about an hour and then went downstairs and took some posters, slipping bills into a small locked box (which had an apology for the lock). I never saw a soul. The Bread and Puppet Theater reminded me that commerciality doesn’t necessarily equal beauty, that there is a quiet madness to regional fame.

11

Affairs happen at residencies, there’s no denying that. I guess it might be part of the appeal for some. My first residency, at the Atlantic Center for the Arts, throbbed with a dangerous restlessness. That one led to roughly five hook-ups (I found out about a sixth almost a year afterward), and precipitated the end of two marriages. I think it’s because there’s a special sort of attractiveness one acquires at residencies—it’s a bubble where you’re at once confident in your work and unusually open, and since time is limited, there’s the drive to act out, risk-free. It’s sort of like camp for adults who were already trending libertine. There was an 8-1 W/M ratio in Vermont, which didn’t slow the rate of affairs but did increase the general sense of experimentalism, of wide-eyed breakfast confessions. I was single in Florida, but this time I was in a relationship. Before I left, I gave my girlfriend Heidi Julavitz’s The Folded Clock without having read it, and a few days in she sent me this passage without comment. I read with rising dread:

“This is also why I get nervous about going to art colonies, especially now that I am happily married to a man I met at an artist colony. I don’t want to fall for anyone else—I am pointedly not looking to fall for anyone—but these situations conspire against our best intentions. Art colonies, often located in remote woods or on beautiful estates, are communities in which all the residents sever ties to the real world within hours of arrival; they are like singles mixers for the married or otherwise spoken for. (I was married when I met my now-husband, who was otherwise spoken for.) When I arrive at a colony these days, I take a measure of the room, I identify the potential problems, I reinforce my weak spots, then I can relax.”

This was what a tennis commentator would call an unforced error.

12

My friend Marisa Finos drove me to a death lecture in Burlington. JR Lee’s infinite burial project started life as an experimental performance piece, but in the manner of the 21st century, she’d attracted investors who left their venture capitalist firm to monetize her concept. As JR explained it, mushrooms are interface organisms between life and death, so she wraps dead people in shrouds that accelerate the fungal process, turning them into mushrooms in a manner of months, giving back to the earth and, if you’re feeling funky, offering sustenance to your loved ones. Since we were in Vermont, a lot of the questions that followed were on the specific types of mushrooms they were using. I found the lecture moving—I always feel unwillingly sarcastic at conventional funerals. Marisa was even more captivated, since her own art has echoes of the project. She buries herself in varying sarcophagi for as long as eight hours at a time. On the drive back, as Marisa raved through the dark, I realized I wanted to write about the way people react to death.

13

Halfway through the residency, there’s an open studio walk. Beer in jacket pocket, I wandered the artist’s buildings and immediately started feeling insecure about the containedness of my own output. In the sculpture studio, I filled the taxonomy of cheese notebook with details. The variety spoke to the ease with which artists assume weirdness. Ian Faden, my karaoke ally, was working on a series of male nudes, all of whom he’d met on Grindr by explaining to the disappointed aspirants that he didn’t want to hook up, but would love to paint them. I also loved the work of Genesis Baez, who travels to Puerto Rico, takes pictures, buries the film on the spot, and digs up and processes it years later. The results are glitchy, gorgeous artifacts. Another Harbach passage from MFA vs NYC:

“What one notices first about NYC-orbiting contemporary fiction is how much sense everyone makes. The best young NYC novelists go to great lengths to write comprehensible prose and tie their plots neat as a bow… the result of fierce market pressure toward the middlebrow… the NYC writer knows that to speak obliquely is tantamount to not speaking at all; if anyone notices her words, it will only be to accuse her of irrelevance and elitism.”

Ian Faden

14

Confident that I had enough material for innumerable expository essays, I asked Saree Silverman, whose naturalistic work involves stringing up thousands of Bougainville petals, on a walk. I regretted it when I learned that it was the first day of hunting season. Freshly adorned in my stylish orange trapper hat, I opened the front door of my house and immediately fought the urge to hit the deck when four men with rifles strolled by. Martial law! Trump ascendant! Then I saw that they were playing with a hackeysack. I didn’t know Saree well, but the fear of being shot had me prattling on more than usual for the purposes of self-defense. I was trying to avoid sounding like a deer, and in the Shakespearean nature of monologue, I articulated truths about the limitations of my work and the stagnation I’d been feeling before the residency. There was that surprise of discovering a pent-up frustration that unwinds as sentences run on. The merit-free world of the residency had let me reconceptualize failure.

15

George Saunders in MFA vs NYC:

“We all love the idea of, you know, Tolstoy and Chekhov and Gorky exchanging manuscripts and passionate letters of critique and so on (or Ginsberg/Kerouac or Hemingway/Fitzgerald, whoever), and so maybe the goal would be for one’s CW community to look something like that: a bunch of artists, living simply and honestly, butting out the crap, trying to construct a happy little petri dish, forming intense friendships that center around, but are not limited to, art, and that continue on through the rest of their lives.”

I had a small, secret writing swap during the residency with Robin Myers, Mexico City-based poet, farmer and essayist Katie Powers, and the dynamic Michelle Blake, poet, fiction writer, and resident of upstate Vermont. Our hours in the library, eating contraband baked goods and criticizing each other’s work, were some of my happiest. We’ve continued the exchange in the months since the residency. In fact, they edited this essay. [So did I—Ed.]

I was trying to avoid sounding like a deer, and in the Shakespearean nature of monologue, I articulated truths about the limitations of my work and the stagnation I’d been feeling before the residency. There was that surprise of discovering a pent-up frustration that unwinds as sentences run on.

16

Jody Gladding, a visiting poet, invited us on a haiku walk. Though some writers resisted, I decided to go, partially out of guilt, partially because I was having trouble with my descriptions. I was working on a horseshoe crab sex scene, and though a haiku walk seemed remedial—this was an exercise I’d done with my own students when I taught at NYU—I thought it might help to stare at some water. It was rainy out, and after I watched Jody and Harriotte walk the yard arm in arm for a bit, I climbed down into the river and wrote six haikus. This was my favorite, and I ended up using it in the novel:

Wind on the water:

The veil complicating, then

Uncomplicating.

Genesis Báez

Photographed on July 12, 2012

Negative buried in Yabucoa, Puerto Rico on March 28, 2013

Negative dug up on April 9, 2013

17

Harriotte asked me to read her work out loud for her when it came time for our group presentation (she can’t read braille). I agreed—“Guernica essay.” When she sent me the memoir excerpt, I saw that I’d made a mistake. There was a horrible sexual assault scene in it, a thing that really happened to Hariotte in Greece in 1967, and she was going to be sitting in a rocking chair next to me while I read it out loud to the audience, which, remember, was something like eighty percent women. It was too intense, too sad, too inappropriate for me, a man, to read it. But I’d given her my word, and I liked Harriotte, and she was so enthused after our initial read-through. Further complicating things, on the day of the reading, she added a bunch of expressions in German to the scene in question, in which she requested I “do the voices.” I got through it, somehow. Normally when I read, I scan the room and lean into my punchlines, but that night I was eyes-down like a middle-schooler running for class treasurer, my face burning as Harriotte laughed while I described her escaping her captor’s house by running her hands along the raspy wall in search of a door seam. But I felt the power of her words on that stage, the potency of writing without a net.

migration is my home

Saree Silverman

2015

18

One of my last nights in Vermont was spent with Jenny Calivas, a non-erotic-nude-photographer. We were out at a bar when she said she had a video project in mind, and immediately assured me that I could remain clothed if I so chose. I was a little offended, but I still followed her to her studio. She told me to emulate whatever appeared on her laptop screen, then turned on a video camera and left me alone in her white room with the naked photos of people I knew all around me. The screen flickered—it was Jenny, dancing, and I was apparently supposed to dance with her. At first I moved ironically, but I began to feel truly alone and rotated and swirled in time to the song, really letting loose. I’ve seen no footage of this dance, and that’s likely for the best (I slowly unzipped my winter coat while spinning at one point), but I do like knowing that there’s a record of my Vermont self out there.

19

In NYC vs MFA, Eric Bennet writes that “within today’s MFA culture, the worst thing an aspiring writer can do is bring to the table a certain ambitiousness of preconception. All the handbooks say so. ‘If your central motive as a writer is to put across ideas,’ Steve Almond says, ‘write an essay.’” This is, of course, an overstatement. Like artists, writers—the good ones—succeed by being weird, but they sometimes struggle to explain that weirdness and fall back on the rules of craft and vagaries of market that accompanied their rise. I think that this sudden belief in external factors explains why second novels, with their calculated weirdness, tend to be bad. MFAs do celebrate ideas, and they’re absolutely worth doing, but it’s also important not to forget the obscure journals, the experimental Olive Garden reviewers, and yes, the writing residencies.

2015

20

On our last night in Vermont, there was a second gallery walk. I threw my own studio door open, stacked 80 new novel pages on my desk, and went to a bonfire to suffer through some below-average wine from a box. I’d forgotten the pleasure of a fire on a cold night, the body alternatingly attracted to and repulsed by the heat. Most writers turned in early, and the artists, of course, stayed up all night. I was something in between. When I finally walked away, I looked across the river. I’d left my studio light on. As I entered, I ran my hand along the doorframe, which was signed by every writer who’d worked there. I hadn’t heard of a single one of them—on my first day it was evidence that I’d made a mistake in coming. Now, it was something of a comfort.

21

I sat with the group on the train back to New York.