On a Wednesday evening this April, I pick up the phone to hear the voice of Houth “Billy” Taing, a 43-year-old immigrant from Cambodia who has lived in the U.S. since he was 5 years old. Despite the static and crackling on the line, I can make out his relief at having reached me. He’s calling from Adelanto Detention Facility, ninety miles northeast of Los Angeles, where he has been held for over six months. Detainees such as Taing can only place phone calls, not receive them. They are also prohibited from leaving messages. Before this call, Taing had tried to reach me three other times.

“Detention” is the incarceration of immigrants who are not authorized to be in the U.S. and who face deportation. Detainees await in prison-like facilities for immigration authorities to decide whether to release them back in the U.S. or to repatriate them to their countries of origin. Taing lives in a small cell with seven other men, in a two-story building that looks like a warehouse, where detainees are shackled whenever they are being transported to other facilities, where barbed wire slices the sky, and where solitary confinement is a form of punishment. He calls me from the common area, which is so loud that we’re forced to raise our voices to hear each other. The detainees’ lives are also regimented like prisoners’. Detainees are allowed outside in the fresh air only four times a week. A few times a day the guards count the detainees, who rise each morning before 4 a.m. for breakfast. Taing says even the meals resemble prison food. He would know. The detainees’ crimes, for which many have already served time, are announced by the color of their jumpsuits: red for the most serious, and orange and blue for the lesser crimes. Taing’s is red.

In 1994 when Taing was 19, he and two others tried to rob a tourist bus headed for Las Vegas. They boarded the bus disguised as sightseers, but then stole money from the other passengers, ultimately forcing the driver to go to a warehouse where they’d stashed a getaway car. Taing and the others were arrested twelve hours later. He was charged with kidnapping and intent to commit robbery, and served more than two decades in prison. Taing regrets what he did and characterizes it as a desperate, youthful act. “I am truly sorry for the pain and suffering that I caused to all those people involved in the crime that I committed,” he says. “I realize nothing I say or do can change the horrific event on that day. All I can do is continue to be a better person and make amends.”

But he hasn’t had much of a chance. When non-citizen immigrants commit crimes, they lose their legal residency status in the United States. This makes them potentially deportable even after they’ve served their time. If Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) believes there is probable cause to remove an immigrant criminal, such as if an immigration judge has signed an order for that immigrant’s removal from the United States, then ICE may pick them up and take them to a detention center.

This is what happened to Taing. Soon after he left prison in 2016, he was detained by ICE for a few months, only to be released and then detained again last fall. Although Adelanto isn’t a prison, some of the detainees here, like Taing, can’t help but feel as if they are reliving their experiences of incarceration. “There’s no difference between being a prisoner and being a detainee,” Taing says.

However difficult it may be, newly freed criminal citizens have a second chance to build a new life. By contrast, the immigrant criminal faces a life of routine check-ins at an ICE facility where the threat of detention always looms. Some are detained immediately after release from prison. Others arrive to their check-ins only to discover they will be detained on the spot, and for an indeterminate period of time that could last hours or even months. Upon release, they recommence their check-ins with the chance of being detained again. It’s disruptive to a steady job and stable family. They never know when they say goodbye to loved ones on their way to work whether they will return. What’s more, they must endure the constant threat of a penalty far worse than detention: exile to their countries of origin, which they may hardly know, where they may have no connections or not speak the language.

Still, it’s hard for many Americans to muster sympathy for the immigrant criminal. In a March 2017 poll conducted by CNN, 78 percent of the 1,025 U.S. citizens surveyed believed that the government should try to deport non-citizen immigrants who have committed crimes. A common narrative dictates that the “good” immigrants own their own businesses, excel in school, volunteer, and donate to charities. The “bad” immigrants or “bad hombres” or “animals,” to quote President Trump, drain the U.S. of its resources, steal jobs, and commit violent crimes.

But in the real world, immigrant criminals often don’t resolve neatly into these simple categories. And many Southeast Asian immigrants whom I have been reporting on, such as Taing, are good examples of this. I spoke with immigrants who came to the U.S. between the 1970s and 90s as refugees fleeing the atrocities of war and genocide. Once in the U.S., they found better lives, but still faced challenges. They struggled to process the traumas they experienced in their countries of origin and to assimilate in the U.S. when confronted with xenophobia. A few turned to crime, including some who were very young, even minors. Once they served prison sentences, many of them emerged as very different people: middle-aged adults, making significant contributions to their communities.

In recent weeks, the U.S. government’s separation of children from their asylum-seeking parents at the border, Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ declaration that domestic violence could no longer be claimed as a ground for asylum, and the confirmation from the Department of Health and Human Services that it would build “tent cities” near El Paso, Texas, for thousands of separated immigrant children, have ignited outrage across the country. And rightfully so. The Trump administration’s treatment of immigrants has been nothing short of barbaric.

At a moment when compassion for the immigrant is already limited, the immigrant criminal is rarely on the receiving end of it. Yet it is inhumane to punish people multiple times for the same crime – first in state or federal prisons, then in detention facilities, and finally in the form of banishment to a foreign land where they will never truly be able to atone for their crime in the community they wronged.

It’s true that Taing committed a crime twenty-some years ago. Other things are also true: “He’s so positive,” says Blair James about Taing. James directs the Anti-Recidivism Coalition, a nonprofit that helps recently released criminals assimilate back into society. She says that Taing was a consistent and enthusiastic attendee who also became a volunteer in the program, until he was detained by ICE last fall. He was a “stellar member of the ARC community,” says James. “Having Billy [in detention] impacted all of us.”

Taing also collected food for the homeless and completed an electrician apprenticeship program through the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. He was his mother’s primary caretaker. “Billy has always tried his best to be there for me and my mom,” says his brother David Tran. “My mom and I have waited over 20 years for him to come back home and for Immigration to detain him is heart breaking.”

Taing longs for his freedom, and fears being deported to Cambodia, where he doesn’t speak the language, Khmer. “I was a productive member of society,” he tells me, sighing. I can barely hear him over the crackling on the line now. “I just want a second chance to take care of my family.”

Despite having escaped from two of the most brutal regimes in modern history, the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, and the communist government of post-war Vietnam that sent citizens to “re-education” camps, Cambodian and Vietnamese refugees were not welcomed by the majority of Americans. They faced racism, and were condescendingly labeled “boat people,” which contributed to the overall sense that their new home country was insensitive to the traumas they’d suffered.

“People forget that part of history,” says Phi Nguyen, who works at Asian Americans Advancing Justice, an advocacy group in Atlanta. “It’s important to remember that Southeast Asian immigration was less popular than Syrian immigration today.” Her own parents barely escaped Vietnam. She credits a few sympathetic community members and her father’s knowledge of some English for her family’s ability to cut through the animosity toward them and thrive.

When Taing was 18 months old and living in Cambodia with his ethnically Chinese family, Khmer Rouge guards forced their way into their home in the middle of the night, smashed the butt of a rifle into his father’s skull, and dragged him away. According to Taing’s mother, the Khmer Rouge accused Taing’s father, a professor of Mandarin and coach of the university’s basketball team, of plotting against the regime. No one saw him again.

The rest of the family fled Cambodia in 1979, when Taing was four years old. For two years they were refugees in Thailand and then the Philippines, before arriving to the U.S. where they finally settled in Los Angeles. As refugees, they received lawful permanent residency status, which put them on the path to U.S. citizenship.

Taing remembers his childhood in the U.S. as a struggle. His mother remarried and gave birth to another child. She was also working retail and assisting with her new husband’s moving company, which left Taing feeling lost and invisible. “I felt like I didn’t have a voice,” he says. As a teenager in their mixed Asian community, Taing felt most comfortable with his peers. But he began hanging around with the wrong crowd, smoking and ditching classes, and ultimately joining a gang. “In my distorted thinking, I thought gang members were my family,” he said. “I felt like I belonged. They accepted me and supported me.”

Tung Nguyen, a 42-year-old ex-felon Vietnamese immigrant, tells me a similar story about his family. “We came after the fall of Saigon,” he says. “We came traumatized and [then we] were bullied and discriminated against in school.” Children like Nguyen lashed out, joined gangs, and broke the law. Their parents were too ashamed, or too distrustful of the police, to seek help.

In 1993, at age 16, Nguyen was present when a fellow gang member killed a man and afterward stole his things. Nguyen was caught and convicted of felony murder and robbery and was sentenced as an adult to 25 years to life. He served 18 years, and was released from San Quentin State Prison, in 2011, under an order by Governor Jerry Brown for saving the lives of fifty inmates. During a hip hop concert at the prison, Nguyen put himself between rioting prisoners and community volunteers on the stage to protect them.

Since he left prison, he’s been a community organizer for juvenile justice reform and immigration rights, and founded API-ROC, an organization that assists with re-entry and immigration services for formerly incarcerated Asian and Pacific Islanders in Orange County. “Tung is a monumental part of our community,” says Lan Nguyen, a fellow community organizer who has attended activist training sessions with him. “He donates so much of his time and emotional labor into helping others.” He is also the primary earner for his wife and stepson.

But despite Nguyen’s success assimilating back into society, he’s often worried. Though he continues to live at home with his family, in 2011 an immigration judge issued a final order of removal. “Take my criminal file and compare it to who I am today,” says Nguyen. “I’m asking for mercy.” He doesn’t know when or whether ICE will detain him, and lives in fear that ICE will target him soon. “I’m just so vulnerable right now.”

ICE was created in the wake of 9/11 as part of the new Department of Homeland Security with an aim to remove “aliens who present a danger to national security or a threat to public safety, or who otherwise undermine border control and the integrity of the U.S. immigration system.” (“Aliens,” widely considered a demeaning term among those in the immigrant community, refers to persons lacking lawful residency status in the U.S). This wasn’t the first time in recent history that the U.S. government aggressively sought to round up and deport criminal immigrants. In 1996, Bill Clinton signed two acts into law that accelerated the detention and removal of non-citizen criminals. But the formation of ICE was a direct effort to capitalize on the newfound fear of global threats post-9/11 by focusing on national security, specifically, the arrest, detention and removal of immigrants. Today hundreds of thousands of immigrants report to ICE, including recently released criminals.

Since Cambodia and Vietnam have historically been resistant to repatriating their nationals, the U.S. hasn’t typically targeted them for removal. “In the past, ICE respected the fact that these people couldn’t be deported, and did not waste their resources in detaining them,” Phi Nguyen says. This has changed under the Trump administration.

Five days after his inauguration, Trump signed an executive order granting ICE wide latitude to detain immigrant criminals who committed any crime. Matthew Bourke, a spokesperson for ICE, says this has resulted in a “little bit of a culture change” at ICE. But for immigrant criminals and their friends and families, the impact has been more profound.

During the first 100 days of Trump’s presidency, ICE arrested 10,865 immigrants with criminal convictions, a 12 percent increase from the same period of time in 2016. Last fall, despite the fact that Cambodia and Vietnam made no assurances that they would repatriate, ICE rounded up and detained some 100 Cambodians and 100 Vietnamese immigrants with criminal records, most of whom were refugees. Although detainees aren’t typically held longer than six months, there is also no hard limit on how long a detainee can remain in detention. In response, two class-action lawsuits on behalf of these immigrant criminals have been filed against the U.S. claiming it’s violating the detainees’ right to due process. In the meantime, ICE plans to open more detention facilities.

Tammy Nguyen will never forget the day that ICE came to her home and took away her husband, Dy Nguyen. She tells me the story on a warm February evening, while we sit at a dining room table in her parents’ home in a suburb of Atlanta as her 8-month-old daughter, Chari, rests on her lap. Tammy is temporarily living with her parents, because Dy can’t help her care for Chari.

In the early morning of November 6, 2017, while Tammy was getting ready to go to her job as a medical assistant, Dy’s mother called and told them there was an officer at her home looking for Dy. Tammy told Dy’s mother to put the officer on the phone. When she did, Tammy asked him if he was from ICE. The agent said yes, and told her that she and Dy needed to remain at their home, because ICE agents wanted to come by and verify Dy’s new address. They’d be there in ten minutes. Tammy knew right then that something was off, because she and Dy had already provided ICE with this information.

Dy, 31, is a Vietnamese immigrant who in 2008 was convicted of stealing property, and served five years at Wheeler Correctional Facility in Georgia. The day that Dy was released, pursuant to its immigration detainer policy, ICE immediately picked him up and took him to a detention center, where he was kept for three months. After his release, Dy worked as a cable technician and as an active member of their church, leading the youth group. Tammy says he never hid his past, and used the fact that he was an ex-felon to teach teenagers to do better. “He encouraged the youth to hold on to the teachings of God,” she says. Now with ICE on the way to their home, Tammy and Dy were praying ICE wouldn’t take him.

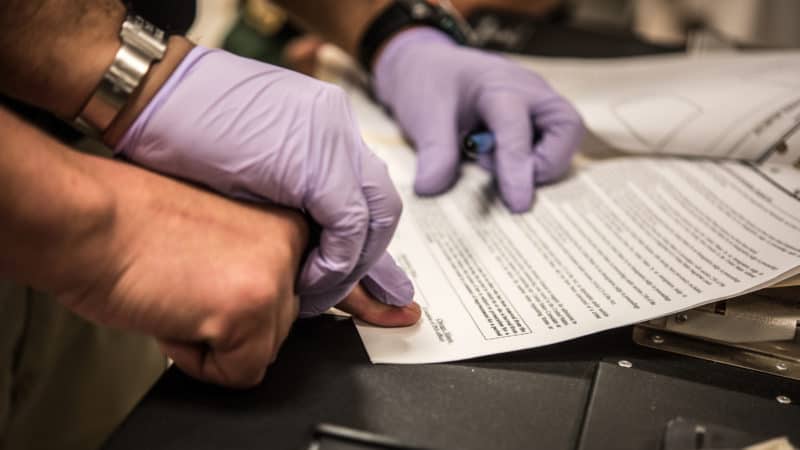

A few minutes after Tammy hung up the phone, three vehicles pulled up to their house and then some ICE agents got out and entered through the garage, where Dy and Tammy met them. Dy was still wearing his pajamas and holding Chari in his arms. The agents told Dy he needed to come with them to the ICE office to update his new address. Next the agents instructed Tammy to get Dy’s shoes, socks, jacket and pants. She hurriedly left for their bedroom, growing increasingly worried about their true intentions with her husband. When she returned with Dy’s things, he was already sitting inside an ICE vehicle, which then drove away. She stood watching, holding Dy’s clothes, in disbelief she didn’t even get the chance to say goodbye.

Tammy is haunted by the thought of raising Chari without Dy, she tells me while bouncing Chari on her lap. “Chari was only five months when ICE took him in,” she says. Chari has an odd sleep schedule, and would wake up from a late nap at 9 or 10 p.m. Dy would play with her and read her Bible stories until she fell back asleep. “He would tell me that this is his bonding time with her,” says Tammy. “He is a sweet daddy.” She tells me how she and Chari only see Dy, who is detained at Irwin County Detention Center in Southern Georgia, through video visitation once a week.

On May 4, a few months after this conversation with Tammy, she got good news. Dy would be released after almost six months of detention. “I was so happy I couldn’t even breathe,” she told me over the phone. On the trip back home, she couldn’t help looking at Dy who smiled the entire 4-hour ride. But the threat of detention always looms, and their joy is tempered with fear. “ICE can get you anywhere,” she says. “As long as there’s a removal order, as long as the Trump administration tries to deport, we will still be scared.

Though the purported mission of ICE is to protect public safety through the detention and removal of “illegal aliens,” its methods and procedures are, to say the least, bizarre. When I asked Bourke to shed light on the reasons behind ICE’s multiple detentions, his answer still left me mystified. “There is no policy against unlawfully present aliens being detained more than once,” he said. “Custody decisions are made on a case-by-case basis. The purpose of detention is not punitive, and is done only until ICE can effect a removal.”

What is certain is that for an immigrant without lawful residency status, a life lived in ICE’s shadow is a life lived in terror. This fact points to a question of justice. Should any immigrant criminal, even one who is not a model ex-con like Billy Taing, Tung Nguyen, and Dy Nguyen, be treated in this way? Although laws, policies and rhetoric pertaining to illegal immigration might suggest otherwise, a noncitizen criminal is no more a criminal than a citizen criminal. Repeated detentions and deportation are brutal penalties that lack any semblance of mercy, going far beyond reasonable forms of punishment.

After six months of detainment, on April 19, Billy Taing was released from Adelanto. “There are no words to describe it,” he says when I spoke with him a few weeks later, just after he finished having lunch at a restaurant with friends. “It’s a great feeling.” I later ask him what his mother thinks. She says in her native language Chui Chou, which Taing translates for me, that she’s so happy and relieved to have her son home. It’s as if she won the lottery.

His brother David is also relieved by his return. “When Billy was first arrested, I was just a kid. Now I am grown and have a family of my own with two kids. I just wish for him to have the same.”

Taing told me that he hopes to find work as a union electrician to help support his mother. His detainment has also inspired him to volunteer for social justice causes, and he’s especially interested in immigrant rights and helping those like himself who are undocumented attain citizenship. He also wears an ankle monitor, just like some 28,000 others whom ICE has deemed a flight risk, and he hopes to have it removed soon. And though he’s reveling in his newfound freedom, his next visit with ICE is scheduled for this July 26. He’s terrified of what could happen when he reports. “Every time I check-in with ICE I know I may never come back out again,” he says. “Every time I go, I need to prepare for the worst.”