In 2011, I was just one of over a million women in the Philippines facing an unplanned pregnancy. But unlike most of those women, as a middle-class American born in the 1980s, I never doubted that, if necessary, I could summon the means and mobility to get an abortion.

I had my first child six months before I was to move halfway around the world to Manila, where my husband, Walker, would train a team of software developers for a New York–based startup. We would be well taken care of: company-paid housing, transportation, child care, occasional airfare to and from New York—more than I’d ever imagined possible after spending the bulk of my twenties barely getting by. We giddily pored over photos of the glass-walled high-rise where we would settle, situated in Bonifacio Global City, a rapidly developing business center and one of sixteen cities-within-a-city—plus one municipality—that make up Metro Manila.

Walker and I had only recently married, mostly for visa and legal purposes while overseas, and we weren’t on the best or most intimate terms. Faced with our first pregnancy a little over a month after we began casually dating, and only five months after we’d first met, we had forced ourselves into a relationship that had never quite settled comfortably around us.

In fact, we had broken up shortly before his company proposed the relocation, and, just a few weeks later, he proposed our matrimonial transaction. It seemed improbable, at best, and likely unwise, to uninstall myself from my New York life—from grad school, from friends, from a comfortable part-time job that allowed me to work from home—and relocate with a five-month-old infant.

Appealing to my newfound maternal sensibilities, Walker promised the move would improve his professional standing, thereby benefiting our son. Despite his initial misgivings about fatherhood, he was by then as fanatically devoted to our baby as I was; I agreed to come along, knowing that I couldn’t, in good conscience, come between our son and his father for a year or more.

On a sweltering September night, we arrived. Stepping into the frigid lobby of our new home, all gold-toned accents and hard, reflective surfaces, where already a twelve-foot Christmas tree stood awaiting decoration, we began trying to rearrange ourselves as co-parents and roommates.

Gradually we adjusted to our new, smaller life. Knowing just enough about local law to even raise the question, I began to wonder if the IUD I’d planned to get—but hadn’t had time to acquire before our hasty move—was available or even legal in our new home. (Legal, though hotly debated, I later learned.) My OB in New York hadn’t mentioned birth control at my postpartum checkup, and I’d forgotten to ask until I was already headed back home on the train. With a DOA marriage and the unrelenting exhaustion that arrives with a newborn, it hardly seemed like a priority anyway.

But human behavior is both mysterious and predictable, and, within a few months, I was pregnant again. From the moment the second line on the home test faded into view, I was seized by an unshakable certainty that this pregnancy was doomed. We went for ultrasound confirmation a few days later. I should have been ten weeks along, but the embryo measured just five. Still, it already had a strong heartbeat—“Just our luck,” said Walker—so once measurements were rechecked, we were sent on our way with congratulations and warm assurances that I must have miscalculated my dates. But you can’t mistake your dates if there’s only one to choose from.

Abortion laws in Catholic-majority Philippines are among the strictest on Earth. While separation of church and state is a constitutional guarantee, modern reproductive health policy still reflects the legacy of Spanish colonial rule; like many former Catholic colonies, it is largely dictated by Church doctrine, and met by Church leadership and lobbyists with fierce opposition at every bid for progress. Consider the embattled Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Law, which seeks to provide free contraceptives, promote sex education, mandate humane care for post-abortion complications, and overturn contraception bans—and took fifteen years from its introduction to its successful constitutionality ruling in the Supreme Court in 2014.

Legal and commonly practiced in precolonial times, abortion was officially criminalized in 1887 with the implementation of the Spanish Penal Code of 1870. The ban was upheld in the Revised Penal Code of 1930, which detailed penalties for procuring, performing, or otherwise causing an abortion—penalties that remain in place today. Prison sentences range from six months to twelve years, depending on the circumstances of the termination, with the maximum reserved for those who perform an abortion without a woman’s consent.

Further protection was granted to the unborn a century later in the 1987 Philippine Constitution: the State “shall equally protect the life of the mother and the life of the unborn from conception,” it read, giving a zygote, embryo, or fetus standing and protection equal to the woman carrying the pregnancy. Popular opinion, though, seems to side with the unborn, and there’s no explicit language in Philippine law that allows for exceptions, even in cases where the mother’s life is endangered. A 2013 bill introduced in the House of Representatives, where it is still live, would give teeth to criminal prosecutions of both intentional and unintentional abortions, and would lengthen prison sentences relating to each level of offense.

Despite an effective total ban on surgical and medical terminations, most recent estimates indicate that over 600,000 abortions occur annually in the Philippines, with only a third likely performed by healthcare providers. These providers, working under threat of loss of license and imprisonment, may not have proper training or equipment, and tend to charge fees that most women can’t afford.

Women face similar penalties for seeking, receiving, or inducing their own abortions, with sentences ranging from six months to six years. Though prosecutions are, at present, rare, complications are not: more than an estimated 100,000 hospitalizations from abortion-related complications were reported in 2012, with at least 11 percent of all maternal deaths attributed to clandestine abortions. Poor women are far more likely to use unsafe abortion methods, like abdominal massage, catheter insertion, or self-induction with medication and herbal remedies.

We were among the fortunate who had a wider range of options.

Though tragic, this isn’t surprising. The Philippines failed to meet United Nations Millennium Development Goals to reduce child mortality and improve maternal health by 2015, or succeed in the hand-in-hand issue of reducing extreme poverty and hunger. Despite a steady decline over the last few decades, the national fertility rate was still well over replacement at 3.06 births per woman in 2014. In a country with soaring poverty rates, harsh reproductive health laws, socio-religious pressures against modern birth control, and unaffordable healthcare, many women end up conceiving more times than the number of children they can bear—physically, emotionally, or financially. While some nearby countries have more reasonable laws, travel isn’t an option for the vast majority of the archipelago nation’s populace. Many have no recourse but to risk their lives and freedom to end an unwanted or unsustainable pregnancy, or else jeopardize their futures and overburden the families they may already have.

We were among the fortunate who had a wider range of options: let the pregnancy take its course, travel to a land of legal abortions, find a willing, qualified local healthcare provider, or, least desirable, attempt to self-induce.

My ambivalence was crushing. Besides my energy being sapped by common postpartum health woes (thyroiditis, mood disorder), the timing was terrible. I wasn’t ready for another child and didn’t want another, not yet. I also didn’t not want one so badly that any of the available options appealed. I futilely wished that things were different, that I could have been out the door and in the stirrups the moment I pissed positive, but the reality was inescapable.

Travel wasn’t out of the question; it would have been a financial strain, but we would have recovered. Navigating international abortion laws to find a place I’d be guaranteed safe, effective treatment as a foreigner, however, was daunting. We knew someone who had sent his prostitute-mistress to Hong Kong, where, despite seemingly narrow parameters, the law is interpreted broadly and abortion is widely available. But I hardly felt comfortable asking our acquaintance—or his wife—for tips. We were entirely out of our depth. We briefly considered tucking it into a visit we were planning to see Walker’s family in Taiwan, but decided it might make for a less-than-best impression on the relatives I hadn’t yet met.

My OB was sympathetic but unhelpful when I hinted that I’d rather not go through with the pregnancy. Having practiced in the US for decades, he was technically qualified, but didn’t have access to the necessary equipment and, understandably, wasn’t willing to take on the personal and professional risk of performing an illegal termination or obtaining forbidden medications for me. I couldn’t help notice while walking the halls of the medical center beyond his office, however, the proliferation of reproductive endocrinologists, many of whom boasted extensive in vitro fertilization experience on the center’s website, despite the papal injunction against it.

As for the last option, the legal and physical risks seemed too great for me to undertake. When I laid out the situation to Gloria, our nanny, she told me the story of her sister-in-law, Joy. Five months into her pregnancy, Joy, impoverished and already a mother of three, had visited Quiapo, a part of Manila known among the desperate-not-to-be-pregnant for its hawkers of ‘menstrual regulation’ products and ‘therapeutic massage’ by manghihilots, traditional healers, outside the Church of the Black Nazarene. She bought a few tablets of misoprostol, a synthetic prostaglandin used for ulcer treatment that has been outlawed since 2002, which, as a side effect, causes uterine contractions. It’s one half of the usual duo of drugs prescribed for medication abortion, along with mifepristone (RU-486), though it can, at an adequate dosage, cause abortion on its own in the majority of cases. Joy washed down the pills with a bottle of unspecified liquor and belly-flopped onto the floor several times. When that failed, she took a second round of meds, bled for three weeks, and finally—fortunately—had a complete miscarriage. She was pregnant again almost immediately.

I read horror stories about women who were turned away by healthcare providers, tortured with aftercare performed without anesthetic, ridiculed when they arrived at the ER with botched abortions. Like so many others up against this particular wall, I knew I couldn’t chance being refused care should complications arise. There was no guarantee that I would even receive genuine drugs or correct dosages. I happened across the website for Women on Waves, the Dutch nonprofit that delivers abortion pills to women in countries that lack access (recently known for their pill drone-drops into Poland), but only until the ninth week. According to ultrasound measurements, I was already closing in on that limit, and didn’t know what effect the uncertain dates of my pregnancy might have on such arrangements. I’d also seen how long it took international mail to reach us, not to mention how customs had riffled through a package of innocuous baby things my mother had sent. There was no way to know if this or other websites offering drugs were monitored, and, though it may have been paranoid thinking, I wasn’t especially eager to test the limits of the “DEATH TO DRUG TRAFFICKERS” notices that hung on the walls of Ninoy Aquino International Airport. Our situation wasn’t nearly so desperate.

The diagnosis drove the point home: we’re all of us made of the same vulnerable stuff.

As time ran out, I grew sicker and sicker with some lingering illness. Over New Year’s I was hospitalized with crippling abdominal pain and dehydration, then released with a vague diagnosis of acute gastroenteritis. The ailment came and went as our indecision dragged on. The fetus continued to exhibit restricted growth, though its heartbeat never faltered. I made a tentative abortion appointment with Planned Parenthood in New York, while Walker tried to push up a trip home we had planned to celebrate our son’s first birthday with family.

Finally, I was so sick that I could hardly pull myself out of bed. I was hospitalized again. Blood, water, bile. The diagnosis was swift and unequivocal: amoebiasis—amoebic dysentery from infection with tissue-invasive Entamoeba histolytica, endemic in tropical areas and the second-leading cause of death by parasite worldwide. I started to scoff, disbelieving, at the gastroenterologist, then realized there was nothing absurd about it. It was easy to forget—and the city is planned specifically to aid this forgetting—the corrugated-metal-and-tarp slums just beyond the line of gleaming skyscrapers in our posh barangay, to forget that I was still in a developing nation afflicted with widespread poverty and overcrowding, to believe that our foreignness and relative comfort somehow acted as a protective charm. The diagnosis drove the point home: we’re all of us made of the same vulnerable stuff. My OB came to my bedside and patted my hand, saying, “We think this has been the trouble all along. You’re lucky you’re not dead!” Given the circumstances, I suppose, You’re lucky to be alive would have been a touch too cheerful.

Because I couldn’t keep my oral antibiotic down, the gastroenterologist added it to my IV, warning that there was a slight risk of miscarriage from administering it that way. I agreed. If I didn’t make it, nobody would. It was late at night when I was finally alone in my overly air-conditioned private room, but Walker, working New York hours, was still online. If it survives this, I think we have to keep it, I typed. I think you’re right, he replied.

I Googled “IV metronidazole and miscarriage,” the lines attached to my arm bobbing along as I typed, and felt reassured by the antibiotic’s Category B rating, essentially “no known adverse effects,” and disappointed in my sudden spark of hope that it might all work out. Never, then or since, have I found any published research to back up my doctors’ claim of an increased risk of miscarriage when the drug is given by IV.

As I continued digging into amoebiasis and its treatment during pregnancy, one story exploded in the search results, obscuring the facts and stats I hoped to find: Pam Tebow’s Focus on the Family commercial for the 2010 Super Bowl and the various permutations of her sanctimonious fish tale in which she claims that her doctors had urged her to abort her “miracle baby” Tim while she was living in the Philippines as a missionary.

In the long-past kerfuffle over the origin myth of some evangelical quarterback, whom I knew only for his practice of an embarrassing and distinctly American-flavored religious spectacle, the real story is impossible to pin down: the details twist and shift depending on the calculations of the narrator, and, presumably, the needs of the audience.

An early account indicates that Tebow contracted amoebiasis and was treated while in a coma (not a symptom) before becoming pregnant, which, of course, wouldn’t have affected the pregnancy. She was then supposedly told that the “strong medications” she was still taking after getting pregnant, despite the short course of treatment normally prescribed, had damaged the fetus and caused a placental abruption, a potentially life-threatening separation of the placenta from the uterus that rarely has a discernible cause (assuming, of course, that those strong medications didn’t include cocaine). Never mind that she carried several risk factors for placental abruption—geriatric pregnancy, four or more previous live births, malnutrition—and refused the prenatal care that would have allowed her to detect and manage the condition, something many other women would have been pilloried for.

In a later interview with Focus on the Family’s Jim Daly, Tebow says that she was first diagnosed with a molar pregnancy—another dangerous condition, which must be surgically removed, can never become a viable embryo, and clearly wasn’t the issue in her case—and told to abort. As she told LifeWay.com, “They didn’t recommend; they didn’t really give me a choice. That was the only option they gave me.”

Later in the interview, she indicates that she was diagnosed with amoebiasis sometime during her pregnancy and discontinued the medication—quite possibly the same one I was taking, in use since 1966—after swallowing one pill and then reading (not from a coma, presumably) a “severe birth defect” warning on the label. In this version, rather than simply asking for a different medication, she suffered through—amoebas, torn placenta, and all—refusing any further medical care, despite the grave risks to herself and the unborn Tim. “If God called me to give up my life,” she blinks into the camera, “then He would take care of my family.”

Except that, during their run through the proffered-abortion gauntlet, the Tebows moved from Mindanao, in the south, to Makati, a chic cosmopolitan financial hub within Metro Manila, where it seems that Tebow was carefully monitored in hospital for the last two months of her pregnancy. Still, she insisted: “They thought I should have an abortion to save my life from the beginning all the way through the seventh month.” Never mind that, even then, a 28-week-plus fetus would have been considered medically viable.

But the truth is subordinate to the message. Whatever happened, it’s a dangerous mindset: the belief-as-fact, anecdote-as-evidence generalization that is the lifeblood of an argument that holds no truck with fact or nuance, one that can so easily be used to subvert the woman-fetus hierarchy. What remains especially maddening to me about the anti-choice crowd is this: Give them a real working model of their dark vision for American women and they’ll still manage to twist it into some sick savior-among- the-savages fantasy.

I could see Makati from my hospital window, past a line of trees that lay beside the Pan-Philippine Highway, and I slammed the lid of my laptop shut. Indignant at what seemed to me a blatant fabrication, and felt in the moment like a personal affront, I was jealous of a fiction, hopeful for a miracle of my own, though I wasn’t yet sure what my miracle would look like.

The day after my release from the hospital, my thirty-first birthday, just as I began to make peace with the bargain I’d struck with myself, I lay down for a nap and fell into a nightmare. I was hurled into an icy, leaf-choked pond at what had been my grandparents’ house, and awoke gasping, huddled into Walker’s side with the chill of dream-water still on my skin, acutely aware of a chemical change within my body. The next night, I called Planned Parenthood and cancelled my upcoming appointment in New York.

A few days later, when he was finally able to fit me in, I went back to my OB’s office. I sat in the tiny waiting room on his small and tasteful lilac velvet sofa and tried to avoid looking at myself in the mirrored wall, knowing that I had only come for a pronouncement of death, or rather, demise. His assistant recorded my blood pressure—low—and weight—down ten pounds since the week before. “You’ve been very ill,” she said, forcing a smile. “Babies find what they need,” then rolled back the pocket door to the inner office, where my doctor sat at his desk. Beyond the desk was another sliding door that opened onto the exam room, and a short corridor with a scrub sink, a closet, and a small water closet at the very end.

I settled onto the minimalist modern black plastic chair opposite my doctor, waiting through a short silence as he quickly studied my appearance. Was I feeling better? Yes, much, thank you. Were the antibiotics working? They seemed to be, yes. He instructed me to go to the next room and mount the exam table. I climbed up on a step-stool, holding the assistant’s outstretched hand and lay down. She tucked down the waistband of my jeans and discreetly inched up the hem of my blouse. The doctor squirted the ubiquitous blue gel on my exposed stomach, gently lowered the Doppler wand, and began searching for a heartbeat. There was nothing but static and a sound like a record scratch each time he slid the transducer over my skin. That and the slow, invariable pounding of my singular pulse.

“I’d like you to have an ultrasound,” he said, “just to be certain. I’m sure it’s fine. The Doppler is rated for fifteen weeks and up, and your baby last measured only twelve or so.” I nodded and thanked him, took the order slip and walked to the women’s imaging center on the other side of the sprawling hospital.

The radiologist flipped on the sound—blank, unwavering, impassive static—and flipped it off.

I was the final patient before they closed for the weekend. First I paid the receptionist, counting out exact change—2,028 pesos and sixty centavos, always the same. An ultrasound tech led me first to the bathroom, then to the exam room, where I undressed and stepped into a replica of the same large tubular floral sheet I was given every time I came. I sat down on the table to wait. The tech returned with the radiologist and dabbed the transducer in gel, pressing it hard into my flesh, turning it this way and that. The curled-up fetus hung there, suspended in a black cone on the screen: no movement, no tiny heart flickering. The radiologist flipped on the sound—blank, unwavering, impassive static—and flipped it off. She and the tech exchanged rapid-fire syllables in Filipino, so fast that I couldn’t catch even the simplest words, which were the only ones I knew. “Your doctor will explain the results to you. I’m sorry,” she added, then turned and clicked off down the hall.

I sobbed loudly, once, then sent a text to Walker at work: it died.

I’ll be right there, he shot back.

I pulled on my clothes, rubber-limbed, like moving through deep water. I wanted to run, but the tech led me to a firm gray couch and told me to sit. Some time later, maybe seconds, maybe minutes, someone pressed a square white phone into my hand. My doctor’s voice was in it. I didn’t know what he was saying, but I knew what he was telling me. He said to come back on Monday. I cried, then stopped. I felt tired, then heavy with the ebb of adrenaline. Then they switched off the lights, and I was out the door. The lock clicked behind me and I sank into a chair to stare through the glass balustrade at the wide marble-glossed lobby below, waiting for my husband to come take me home.

How much time had passed before I caught sight of him in the empty lobby and watched him take the wide marble stairs, two at a time, up to the balcony, as I stood up, uncertain on my feet, I couldn’t say; suddenly he was there in front of me and I slumped into his arms. We walked out of the hospital and into the dispassionate tropical sun; Walker hailed a cab on Rizal Drive. It was a typical specimen, an aging white sedan with inaccessible seat belts and the name of the taxi company painted in black on its side: Golden Boy. Sitting on the grimy red velour seat covers, I held Walker’s hand, staring silent and unblinking at a little statue of the Virgin stuck to the dashboard next to a flocked plastic daisy nodding along to the rhythm of the tires from its plastic pot.

The following Monday, when I should have been a little over eighteen weeks along by dates, I learned that the fetus had measured thirteen weeks, which put the date of demise right around the time I had suspected. The doctor did a quick exam, but my body remained locked up tight as it gradually disassembled and reabsorbed the fetus, undoing its work like a frustrated knitter. When the body doesn’t expel a failed pregnancy, it’s called a missed miscarriage, or ‘missed abortion’ in medical parlance. The aptness of the term wasn’t lost on me.

Although no other entity within my body could possibly be construed as living, again I’d run up against the scarcity of potential abortifacients, even for ‘legitimate’ medical purposes. Due to strict control on items like laminaria sticks and misoprostol to soften and dilate the cervix, and because of the particulars of my miscarriage, my doctor didn’t feel he could safely perform a dilation and curettage. The operation is more complex in the second trimester; he didn’t want to put me at undue risk for future problems.

“You make beautiful children,” he said. “And I’d like for you to make more in time.”

Instead, he advised that I wait until our trip home, which we’d succeeded in bumping up a couple of weeks. There was always a chance I would spontaneously miscarry—not, I hoped, during the long-haul flight—and there were risks either way, some of which could be exacerbated by air travel: infection, blood clots, sepsis, and a particularly ominous condition called disseminated intravascular coagulation, in which small clots form in the blood vessels, blocking blood supply to the organs and leading to uncontrolled bleeding once the clotting proteins are all used up.

Once we’d gone over the details, he told me about a couple from a nearby province with whom he was consulting. Their fetus was discovered to be anencephalic, with no brain at all and only a partial skull. The mother had little choice but to carry on and deliver when the time came. My doctor had hoped to console me with this anecdote, but all it did was compound my own sense of defeat with a profound grief for the unknown couple. How could lawmakers and ecclesiastics orchestrate such cruel fates for the people they were sworn to serve, all under the guise of morality and the preservation of life? How could humans do that to other humans and still claim their humanity?

My doctor palmed me a couple of packs of contraband Plan B on my way out, and winked. “For a rainy day.”

The next morning, I told Gloria what had happened, willing the tears that threatened to break—for the past we’d just fought through, the potential futures that had suddenly vanished, the rapidly receding hormones, the struggle that still lay ahead—to hold.

“God provides!” she said, beaming and clapping her hands on my shoulders. To a nonbeliever like myself, the acceptance of the mysteries of nature and our lack of control over them inherent in that statement offered an interesting and eminently pragmatic take on the situation. Though it left me wondering: Where would God draw the line in all that helping-me-for-helping-myself business?

In all, I waited three weeks for a dilation and curettage, thanks to the oppressive laws of one country, coupled with the inefficiencies of the US insurance system. In case things went south on the plane, I packed pads and towels, compression stockings and a change of clothes, popped an aspirin the night before to ward off clots. Like most women who miscarry, I never learned the cause—whether it was the illness, the treatment, or simply a defect incompatible with life. Since I hadn’t suffered a series of losses, insurance wouldn’t cover fetal testing. The doctor at Mount Sinai who performed the procedure told me that the fetus’s foot had measured small, which could have indicated a genetic disorder or could have been completely normal individual variation. She couldn’t even tell me what the sex would have been because the tissue was too degraded.

It could have been much worse. I was one of the lucky ones, privileged with an outcome and opportunities not available to most women in similar situations. We could have supported another child. When the pregnancy failed, I was able to travel home to a place where I could still have surgery safely, legally, without unreasonable danger to future reproduction. I suffered no permanent physical injury, deformation, or death; my son didn’t lose his mother. I was forced to live for several weeks with the grim knowledge of my own morbid contents, but the medical catastrophe I lived in fear of never materialized. We went on to have another child, and today we’re back in New York, alive and all relatively well, and my marriage has become a reasonably happy one and, better still, easy, comfortable.

The forty or so weeks of human gestation seem to contain near-infinite opportunities for error. The notion of a perfect human is a fallacy, but there are limits to what is survivable or, from individual to individual, even desirable to survive. The Zika virus, previously considered relatively harmless, is spreading through Central and South American countries, many with abortion and contraception access not much better, and in a few cases worse, than the Philippines, and could conceivably make its way into areas of the US where reproductive healthcare is already diminished and further imperiled. With its suspected causal link to microcephaly and other birth defects in Brazil, we’re right to be concerned and we’re right to be cautious: the conditions associated with microcephaly can be devastating—outright lethal or permanently, profoundly debilitating—for sufferers and their families.

But it’s useful to remember, as dire as it seems, that this is only the latest in a relentless stream of threats to the continuation of humankind, which began for humanity before humanity began and will continue until the last generative humans are gone from the earth. For all we can do to ward away danger, behind each new epidemic is another waiting to take its place. We can take precautions but never completely escape the risks in our world and within our own bodies: environmental contaminates, malnutrition, unlucky spins of the great wheel of genetics. Missed miscarriages like mine may be rare, but they do happen. There will always be someone nearby mourning a future they’d staked a premature claim on, and as long as universal reproductive rights remain an unrealized hope, there will be women risking their lives and health to end unwanted pregnancies, carry unviable fetuses, bear dead and dying and suffering children. What we need, always, is more nuance, more flexibility, not less.

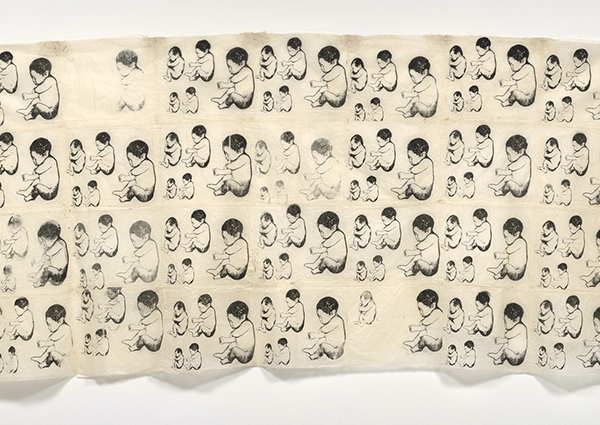

When I think of it now, when I think of it at all, the abortion I missed and the missed abortion, I picture the family that might have been superimposed on the family that is. A tiny foot, all I can imagine of that potential person who never came to be, behind the strong foot of my second son, real in my memory and real in my hand. Women like me, graced with means and choice, shadowed by the millions who, by accident of geography, have neither. What happened, what didn’t, a phantom negative before a wide-open eye.