Mediterranean Floor, 2012, 75 x 150 cm

All photos courtesy Lawrie Shabibi and the artist.

Bethlehem-born Larissa Sansour is a multi-disciplinary artist currently living and working in London. In 2011, she was a subject of controversy when she was disqualified as a finalist for the Lacoste Elysée Prize for her body of work Nation Estate. The work was labeled too “pro-Palestinian” by sponsoring French fashion brand Lacoste. Despite the scandal, Sansour was able to complete her work, eventually launching the completed project at both the Photographic Center in Copenhagen and at Galerie Anne de Villepoix in Paris.

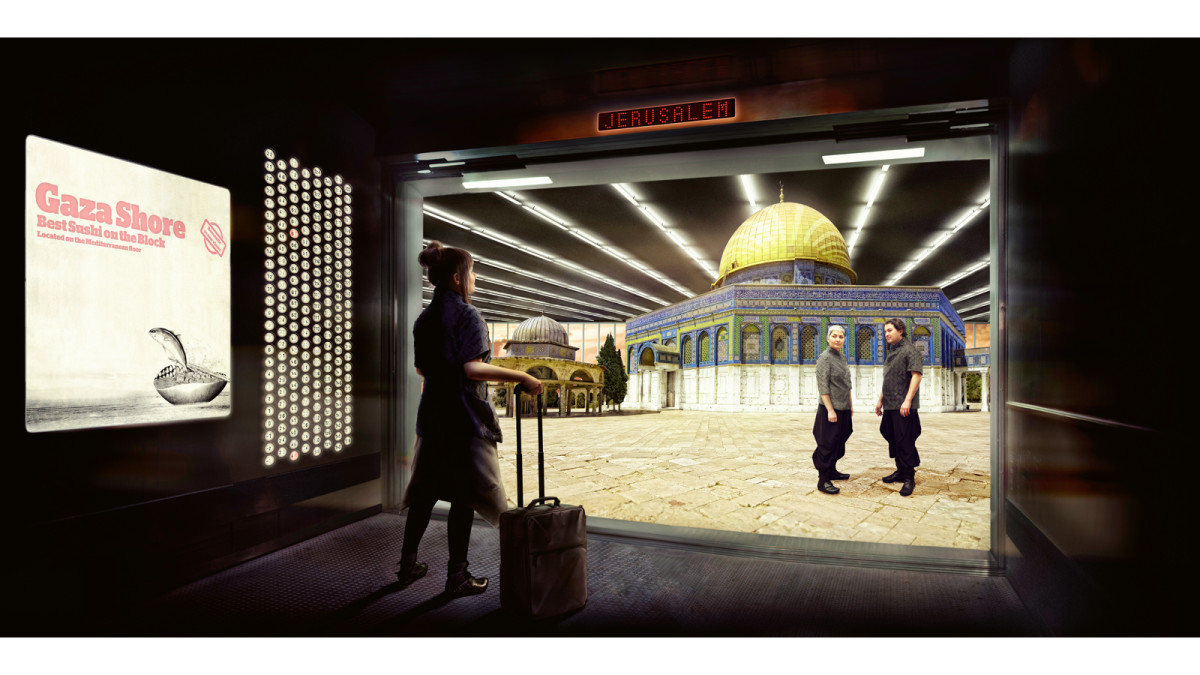

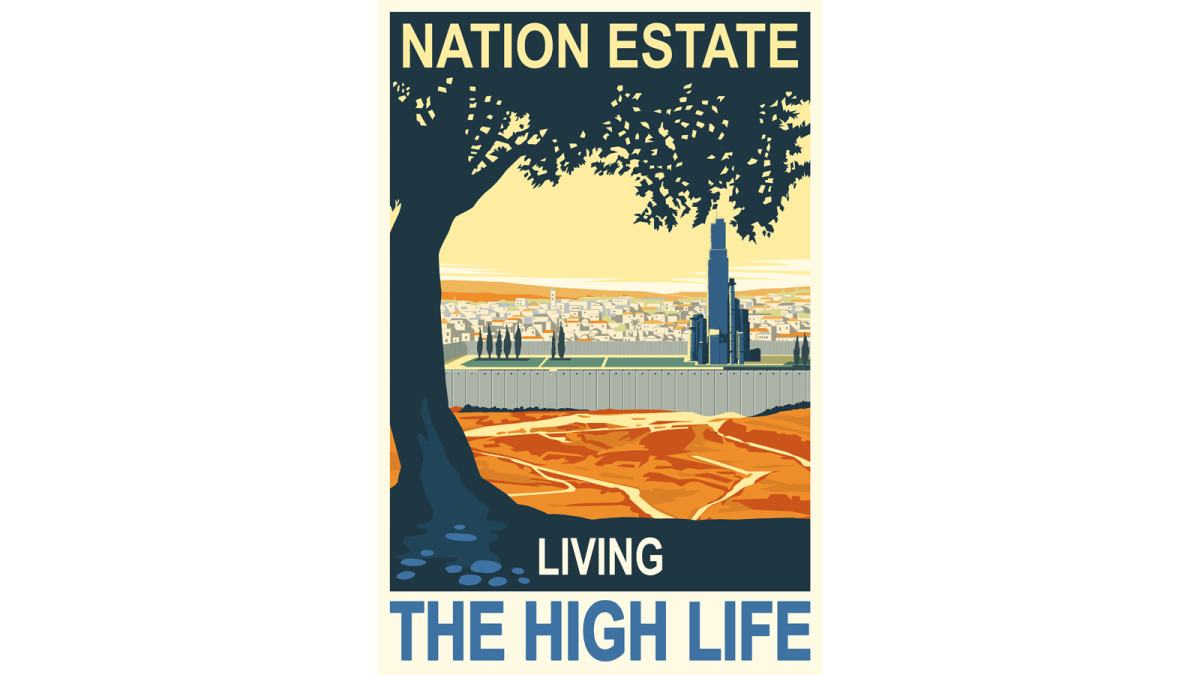

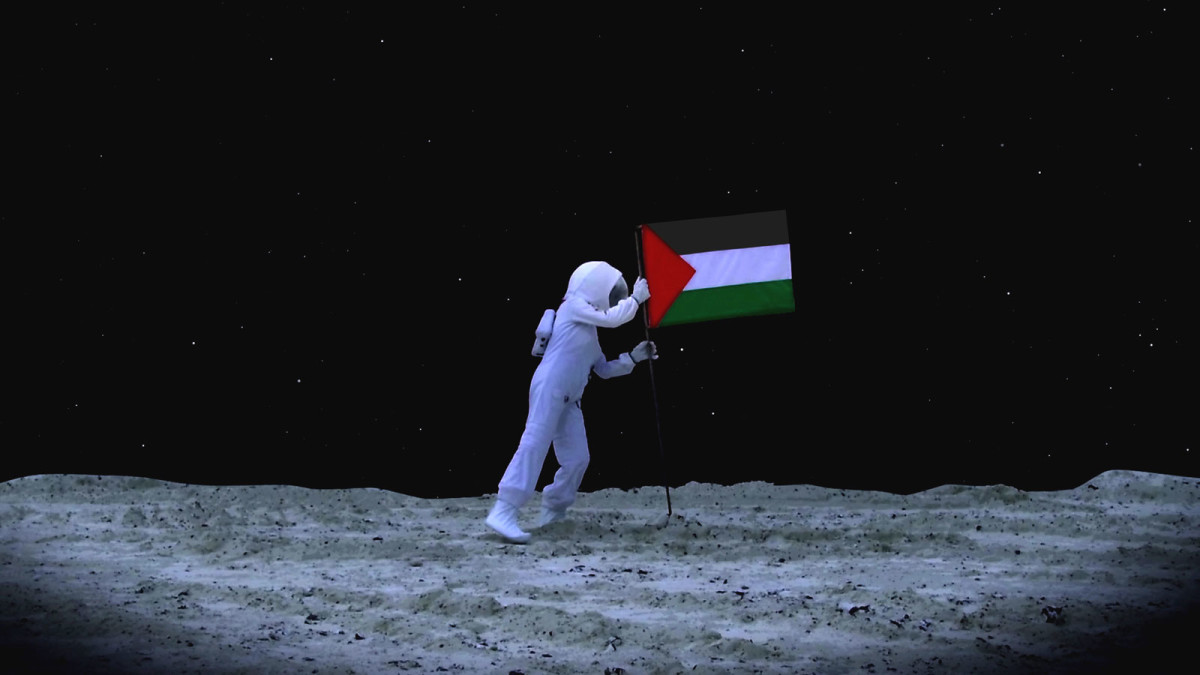

Nation Estate consists of a nine-minute sci-fi short film and seven photographs. Sansour herself plays the protagonist, navigating through a building where each floor represents a futuristic Palestinian city. In the photograph “Jerusalem Floor,” Sansour has arrived, suitcase in hand, to an indoor Dome of the Rock with overhead fluorescent lighting. The environment is a controlled utopia, reminiscent of an architectural rendering. Another photograph, “Mediterranean Floor,” continues the theme. The ocean is contained within a room akin to a hotel ballroom, so that it looks like a luxurious pool, a private fantasy. An older series of Sansour’s, A Space Exodus, which borrows from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, features the artist claiming the moon with a Palestinian flag.

I interviewed Sansour by email about her current show, Science Faction, a compilation of both A Space Exodus and Nation Estate at Lawrie Shabibi gallery in Dubai.

—Haniya Rae for Guernica

Guernica: Has your work changed since Nation Estate first showed in 2011?

Larissa Sansour: It’s hard to think of the piece now without considering it in the context of the Lacoste scandal, so in that sense the work has acquired a new meaning—informed by my removal from consideration for the prize and the events that unfolded afterwards. These events unmasked a lot of what is at play in power relations between artists, institutions, and funders.

The energy that artists, activists, and media extended to this case was astounding, and it catapulted the role of artwork from being that of a critical commentary to in fact being instrumental in the politics at play. What I’m most fascinated by is the ability of art to induce such changes, but remain grounded solidly in its art practice.

The work has also acquired a new political potency in the context of the Lacoste Prize. The project is now preconditioned to be controversial, something that I never really thought was a given, but that I now take for granted. In light of all that happened, the work is much more dangerous now than when it was originally conceived. I also know from the tremendous feedback I have been getting worldwide which particular elements are potentially provocative, so I have been fine-tuning the layers of meaning in a much more conscious way. It’s amazing to have an exchange with such a wide audience before the work is even completed.

Nation Estate is by far the most ambitious project I’ve worked on, in the amount of work and team size, but also in terms of its flexibility. I see the project as laying a structure for a universe that can be revisited many times rather than a closed and finished chapter.

Guernica: Can you discuss the symbolism of the olive tree growing indoors in your work?

Larissa Sansour: What’s great about science fiction is that it allows for surreal scenarios even if they pertain to the real world. In Nation Estate, the concept of national identity is transformed into that of a relic, where it’s showcased in a cold, museum-like environment, where cultural elements are ordered and categorized, where cities appear neatly each on their assigned floor.

The olive tree in the film and photographs is an an organic element, whose roots breaks through the orderly slick floor of the building, in rebellion, one might say.

Guernica: You’ve been using science fiction to describe your ideas. What made this genre attractive to you?

Larissa Sansour: I think I’m most comfortable when I function in a parallel space that’s not separate from political reality, but somehow comments on it from a different portal. The crisis in the Middle East has been ongoing and repetitive and I feel solutions on the ground have reached an impasse. It is somehow necessary to change the way we approach commentary on the subject. I do think that erecting a meta-space that functions according to its own autonomous abstractions and logic could be more effective in finding ways of dealing with the problem at hand, than using our standard tools of analysis.

I am also very fascinated by the idea of hyperbole in subject matter as well as production. I like the idea of going overboard in producing an art piece and I like the way it brings the work away from a meditative space of reflection to a more direct, impactful tool that can compete with the mainstream. I like all these power plays, which have a lot to do with contextualization. In turn, I’m interested in creating crossovers between creative disciplines and in a way in subverting the expected role of the artist in society.

Science fiction also provides a sense of nostalgia that is always present when it comes to Palestine, in that whenever we talk about Palestine, it is never in the present, but either remembering a past or imagining a better future. Submitting gritty Middle Eastern politics to high production sci-fi in this manner not only underlines the absurdity of the situation, but brings about a dystopian future scenario. While the fictional realm as such allows for the obstacles of present-day politics to be altered, neglected, and negotiated at will, sci-fi seems to embody ideals, expectations, and fears of the future that are quite adequate for describing the Palestinian predicament. Somehow managing to fuse nostalgia and hopes for a better and more efficient future, sci-fi seems to lend itself to capturing the decades of Palestinian yearning for a utopia that almost seems dated by now.

Guernica: There’s a lot of humor in your work, given your topics are very political. Why use humor?

Larissa Sansour: The irony or humor of my pieces is never really calculated, but they somehow always end up that way. Humor, especially when dealing with matters of extreme gravity, has a way of toppling set ideas and opening up new modes of interpretation. Furthermore, adding humor tends to shift the power balance. In the case of Palestine, circumventing the expected seriousness tends to open people’s minds and encourage a less inhibited approach to the subject.

Guernica: How might you extend this series in the future? What are your ideas for the continuation of this project?

Larissa Sansour: One idea is to explore the Souq (the market) in Nation Estate and see how that transpires. What I find most interesting is the intersection between fiction and concrete life, so in a sense it would be great to find ways in which these objects in the future can appear in the present. One project I’m already working on that’s heavily based on Nation Estate is an investigation of archaeology and how digs can determine cultural DNAs. It is fascinating how we build narratives and tell histories and how these stories are always laced with an element of fiction.

Larissa Sansour was born in East Jerusalem and studied fine arts in London, New York, and Copenhagen. Her work is interdisciplinary, immersed in the current political dialogue and utilizes video, sculpture, photography, installation, the book form, and the internet. Recent solo exhibitions include Galerie Anne de Villepoix in Paris, Sabrina Amrani in Madrid, Photographic Center in Copenhagen, Kulturhuset in Stockholm and Depo in Istanbul. Sansour’s work has featured in the biennials of Istanbul, Busan and Liverpool. She has exhibited at venues such as Tate Modern, London; Brooklyn Museum, NYC; Centre Pompidou, Paris; LOOP, Seoul; Al Hoash, Jerusalem; Queen Sofia Museum, Madrid; Arken Museum of Modern Art, Denmark; Centre for Photography, Sydney; Courtauld Institute, London; Cornerhouse, Manchester.