The cybertaxi pulled up at the astroport entrance. Lifting the hatch, Buca extracted her long legs from the cab. Right leg first, then left. Then she straightened up with studied lassitude, hewing to her motto: Always be sensual.

Selshaliman imitated her on the other side, and she envied his naturally dignified movements. With their shiny, grayish chitin exoskeletons, Grodos had the rigid look of men wearing medieval armor. And majesty, plenty of it.

But Grodos also had their advantages. She watched Selshaliman pay for the taxi with his credit appendage. His rapid, quasi-mechanical gestures were still extremely unsettling to Buca. He was like a gigantic spider or praying mantis. But the image became more bearable when she recalled that she would soon have the human equivalent of a credit appendage: a subcutaneous implant reflecting the generous bank account that this exotic had just established in her name.

They went inside. Buca took in the last terrestrial sights she would see for a long while. The microworld of the astroport.

The astroport and the neighborhood around it were swarming with traffic, as always. Xenoids just arriving, avid for emotions and already being hailed by the network of tour operators from the Planetary Tourism Agency. Xenoids leaving the planet, exhausted and loaded down with cheap, picturesque souvenirs.

All sorts of them were there. Non-humanoids, like the enormous polyps of Aldebaran with their slow rolling motion on that one round, muscular foot; or the Guzoids from Regulus, long, segmented, and scaly; or the Colossaurs, stout and armored. And also humanoids: Cetians and Centaurians. The former, svelte and gorgeous; the latter, blue and distant.

There were also humans, like that group getting off an astroport shuttle and practically racing to get inside. They looked like scientists, all of them nervous. They were probably off to some conference and they were all clustering around one fairly young guy who seemed to be the lead investigator, though he looked confused, too. Obviously, this was their first trip off the planet. But they were also privileged in their own way. Buca envied them a little. Earth allowed its citizens to leave only on very rare occasions, and only under very special circumstances. Probably some xenoid scientists wanted their human colleagues to attend their event and had paid all the travel costs and taken care of the paperwork.

You could even see a few mestizos here and there. Like that girl with the large eyes and the bluish skin. The Centaurian with her might be her father. Ramrod-straight, like all the rest.

The girl had to be famous, because her face looked familiar to Buca. Maybe some simstim star, or a rich heiress—or, more likely, a social worker like herself, but higher ranking. She couldn’t quite remember—it’d come back to her later. It wasn’t important, anyway.

Selshaliman moved his antennae nervously; he would rather have taken a teletransport booth to the central ring instead of crossing the whole thing on foot. He seemed uncomfortably aware of being the only Grodo around.

These insectoids were crazy about security. They had their own network of teletransport booths and private communication circuits. A silly, overpriced whim, in Buca’s opinion. But if they could afford it… After the mysterious Auyars, the Grodos were the most powerful race in the galaxy.

They were telepaths. That was the foundation of their vast commercial empire. Maybe they couldn’t read the thoughts of other species, but picking up on the moods and emotions of everyone they talked with put them at a very appreciable advantage in all their commercial deals.

A freelance social worker had to be very careful.

She looked at him distrustfully. People said they were incapable of picking up and interpreting the thoughts of humans as sharply as they could those of their fellow Grodos. But still… Just in case, she closed her mind, humming the opening bars of a catchy current technohit, a trick she had picked up from her friend Yleka.

A freelance social worker had to be very careful. Never let her guard down. She couldn’t rest until the hypership had taken off. So many stories were going around… Some social workers had put their trust in Xenoids who later turned out to be humans, disguised with bioimplants. And they’d paid for their gullibility with months or years in Body Spares. She looked around her: in the astroport, too, the booths were everywhere. Inside them, bodies in suspended animation. Waiting for a client.

As if in reaction to her gaze, at that very instant the door to one opened and its occupant came wobbling out. Buca tried not to look, but… She breathed a sigh of relief when she saw it wasn’t him. Since Jowe had been arrested, every time she saw someone come out of a booth she was afraid of finding him with empty eyes.

Some races were biologically incompatible with the terrestrial biosphere, such as the Auyars. To enjoy the tourist paradises that the planet had to offer, they had created this system of Body Spares. All the parameters of the “client” (memory, personality, intelligence quotient, motor skills) were computer-coded and then introduced into the brain of a host-human. The Xenoid gained both mobility and access to all the skills and memories of the “spare body.” There was just one minor detail: forty percent of the time, the person whose body and brain were occupied by the extraterrestrial remained conscious.

When the process was in its experimental phase, being a “horse” was voluntary, and almost well paid. But there weren’t enough volunteers, and it became clear that there could be aftereffects. Now, the sentence for any offense was a certain number of days, months, or even years in Body Spares.

It was the modern equivalent of Russian roulette; not all “riders” took equally good care of their “horses.” Some tourists pushed them to exhaustion, then simply paid the resulting fine. It was so cheap. Many humans lost their minds after being treated that way for five or six weeks. There were even rumors floating around that at Body Spares they tried to get all the spares to lose their minds. A suspiciously ambiguous law stipulated that you only had full civil rights if you enjoyed perfect mental health. Any obligation to return the use of a body to its legitimate owner would automatically vanish if he or she went schizophrenic.

Buca thought of Jowe, so sensitive and delicate. He wouldn’t last two months. He was probably wishing he would die already. But maybe—the idea was unlikely, she knew, but it was comforting—some wealthy and powerful Xenoid had picked him. And now he was wrapped up in important negotiations with top officials from the Planetary Tourism Agency. That would be so ironic.

Human and Grodo, they walked through a giant hologram of Colorado’s Grand Canyon.

She only prayed that he wouldn’t be “mounted” by an Auyar. They didn’t mind paying the fines, no matter how steep, and they always destroyed the bodies they used as “horses.” The Grodos seemed trusting and naïve in comparison with the Auyars, whose paranoia seemed to be second nature. They were ultra-protective of their privacy. Nobody knew what they truly looked like.

Human and Grodo, they walked through a giant hologram of Colorado’s Grand Canyon. Ahead of them, two Aldebaran polyps were silently talking with their tentacles, completely engrossed. Buca watched them in amusement: after the fluorocarbonate pollution of the twentieth century, and after being strip-mined for minerals by a corporation from Procyon, the place wasn’t even a shadow of that image.

She noticed with pride that Selshaliman was also stopping to admire the panorama. One of the few things the terrestrials could feel proud of was the well-oiled machinery of their advertising and Xenoid tourism industries.

Buca had been with an ad designer for a couple of months, and she knew some of the tricks of the trade. Colors imperceptible to the human eye. Infrasound and ultrasound. And recently, even telepathic waves for the Grodos… It was a bit of poetic justice if the Planetary Tourism Agency exploited the Xenoids’ special abilities to drain their bank accounts.

They were coming up to the first checkpoint, which was surrounded by the inevitable Court of Miracles: self-employed businessmen, illegal moneychangers, drug peddlers, and freelance social workers. And, standing discreetly apart, waiting for offers, and very elegant in their tight, black leather clothes, tall, handsome young men who did male social work. It was completely against the law, and Planetary Security cracked down hard on it, in theory.

All of them struggled against each other and with the tourists to earn some credits. Just a month earlier, Buca had been part of the show, not a witness to it, in a different astroport. But it was always the same, and with the same actors. The Disabled Veteran who would show you his radioactive stumps for a few credits. The Victim of Body Spares, drooling piteously and holding a trembling hand out for alms. The Persecuted Believer, begging for help to finish his sacred pilgrimage. The Poor Mother and Her Dirt-Stained Daughter in a corner, watching everything with the eyes of abused animals. The Rich Man Down on His Luck, feigning dignity to sell his skilled forgeries, alleged remnants of a family inheritance. The Endangered Species Vendor, with his hidden cages full of solenodons, talking parrots, or leopard cubs. The Orphan Girl, who for a hundred credits would show off her family photos—and everything else, and then she’d try to con or assault her extraterrestrial benefactor. The Fun-Seeking Young University Student, who wasn’t poor (that had to be clear), but wouldn’t sneeze at a few credits or a polite invitation to eat, if some generous humanoid who shared his same-sex tastes were to invite him… The fauna that all the tourism guides warned about.

Buca recalled Jowe’s words: They only existed because they were tolerated. A façade of false naturalness, a risky alternative for tourists avid for strong emotions. The black market of self-employed tour operators. Their homemade products and services made the sophisticated efficiency of the Planetary Tourism Agency look good merely by contrast—and the agents of Planetary Security were keeping watch in the background, making sure the “self-employed” never became a real danger for the tourists.

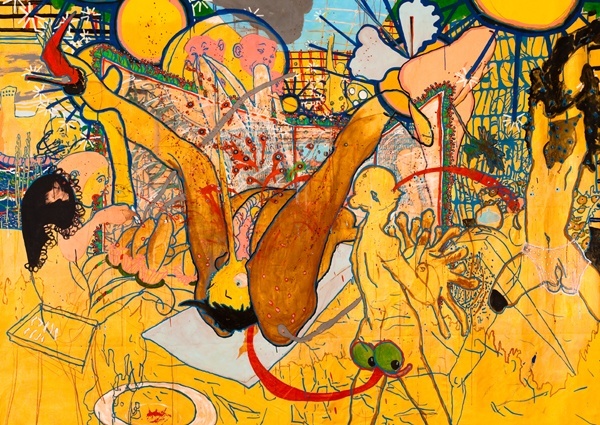

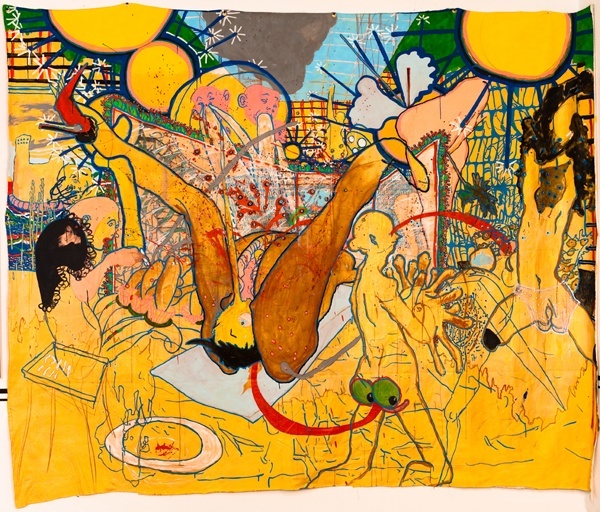

Among them all, the freelance social workers stood out. Super-tall fluorescent platform shoes, forcing them to walk with a gait that could look sinuous or simply unsteady, like balancing on stilts. Clothes tight as a second skin, too short, semi-transparent, or featuring a seductive play of light. Designs meant not to be suggestive but to put everything right out there on display. To leave the smallest possible portion of the meat for sale to the client’s imagination. Buca looked at the women, half-amused, half-repulsed. They were her past.

She compared them with her reflected image in the polished plastometal walls. She wasn’t one of them anymore. She had ceased to dress in the lascivious uniform of desire. She was wearing a pseudosilver ensemble that molded itself to her svelte form, suggesting it without clinging shamelessly to her body. The hues of the fabric shifted, interacting with her biofield. Only her face and hands were exposed; she had already displayed enough skin to last her a thousand years. This was the sort of dress the elegant humanoid ladies of Tau Ceti or Alpha Centauri wore. Her skin was almost pallid enough for her to be taken for a Centaurian.

Maybe she should have bought that skin dye. Pastel blue. It would have heightened the illusion, and Selshaliman wouldn’t have minded. Xenoid women were simply more distinguished.

Being with Selshaliman was all it took for her to breeze through the second checkpoint without being bothered. Only authorized social workers could enter this ring freely. Freelancers had to be accompanied by a Xenoid to get inside, at least for the time being.

The sudden pandemonium of colors and sounds bewildered Buca for a second, as it always did. The middle ring of every terrestrial astroport was a zone of carefully controlled tolerance. Restricted to travelers passing through or tourists eager to take advantage of the reduced customs duties. Social workers of every race and size, each dressed more provocatively than the last. And their male counterparts, in their black synleather uniforms. Native crafts, souvenir shops, all the tourist paraphernalia you found everywhere, all over the planet. But more artificial, cheaper, and more concentrated. Buca stopped in front of a hologram of New Paris. Before it was a half-melted piece of metal that, according to the sign, came from the actual Eiffel Tower.

She had never been there. There were so many places on Earth that she might never get to know .

It didn’t matter that New Paris was just a plastometal reconstruction of the old, authentic city, leveled by a nuclear blast in the days following Contact. Like all terrestrials, Buca felt great pride in the Earth’s past glory. In Greece and Rome and the Aztecs and the Incas and Genghis Khan and the Mongols and the pyramids and the Great Wall of China and the Indian rajahs and the Japanese samurais and Timbuktu and New York.

Selshaliman also stopped in front of the hologram of New Paris. Hadn’t he ever been there? It was ironic. Whatever the Earth was today, it was all due to them and their money. And they didn’t take advantage of it.

“Welcome to Earth, the most picturesque planet in the galaxy. Hospitality is our middle name! We’re only here to make you feel better than you feel at home.” Laughing, Buca recited one of the omnipresent slogans of the Planetary Tourism Agency. Then her lips twisted into a smile and she looked at Selshaliman with barely concealed hatred. There was also the other past. The one described in elementary school interactive texts. One of the few things the Planetary Tourism Agency handed out free to every inhabitant on the planet.

A relatively recent past. When people were already traveling to the cosmos in primitive ships, but many of them still refused to believe in Xenoids. When Earth had different countries and many tongues instead of the one unified Planetary language. Cattle, crops, fish, and game in abundance, but also plenty of hungry people. When civilization was always on the verge of collapse. Because of nuclear war, pollution, the demographic explosion, or all of it together.

But Contact happened.

The minds of the galaxy had been keeping an eye on humans for thousands of years. Without interfering. Waiting until they were mature enough to be adopted by the great galactic family. But when the total destruction of Earth seemed inevitable, they broke their own rules and jumped in to stop it. Their huge ships landed in Paris, in Rome, in Tokyo, in New York. Their desire to help and their resources seemed endless.

The terrestrial leaders—jealously protective of their power in the presence of vastly superior minds and technologies—deemed this altruistic intervention an invasion. And their reaction was violent. Arguing that offense was the best defense, they sounded the trumpets and shouldered arms. Nuclear arms.

The surprise attack caused a few atomic explosions, like the one that wiped out Old Paris. But there was no nuclear war. The Xenoids prevented the other missiles from going off, and then they revealed their full might. When they deployed the geophysical weapon, Africa disappeared beneath the waves. They gave one week’s warning, but the obsession with secrecy among the governments and the disbelief of the masses were the real reasons for the disaster. More than eighty million humans perished in a matter of hours.

After that horrendous incident, the extraterrestrials delivered their Ultimatum: since the terrestrials were incapable of intelligent self-government or of using their natural resources rationally, from that moment on they would cease to be an independent culture. And so they assumed the status of a Galactic Protectorate.

Less than a century later, Earth was once again the natural paradise that had seen the birth of man.

To reestablish the damaged ecological balance, the planet’s new master issued draconian measures: zero use of fossil or nuclear fuel. Dismantling of the great industrial and scientific centers. Zero demographic growth. There were global protests, which were put down efficiently and bloodlessly. Total deaths: not even a quarter of a million.

Less than a century later, Earth was once again the natural paradise that had seen the birth of man. With practically all its non-green surface turned into a giant museum, tourism was the major (and almost the only) source of income for the planet and all its inhabitants. Tourism, controlled by the nearly omnipotent Planetary Tourism Agency, with huge investments of extraterrestrial capital and deep concern for the future of Homo sapiens. A brilliant future awaited human beings under the benevolent tutelage of the galactic community, into which they would be accepted one not very distant day, with the rights of full membership. At least, that was the official story.

Buca, like everybody else, knew that the truth was something else entirely. If it were up to the Xenoids, humans would never be a race with equal rights. Xenoid altruism wasn’t what had motivated Contact. And it wasn’t the hope of saving humanity that had made them interfere, cutting off any possibility of the planet’s independent development at the root.

Jowe had explained the real motives to her. He knew something about Galactic Economy—one of the subjects strictly forbidden by Planetary Security. You could study it in the secret cells of the clandestine Xenophobe Union for Earthling Liberation. No wonder they were persecuted. Or that he had been condemned to Body Spares just because he was suspected of having links to them. Though, most likely, the Yakuza had played some part in the affair.

Jowe used to say that the whole galaxy was engulfed in a cruel war, like all wars, with offensives and counterattacks, with diversionary movements and tactical retreats. But this was commercial warfare: for new technologies, for markets, for clients, for cheap labor. Humankind had been a loser in that conflict from the get-go. And as such, it was condemned to be a client, never a rival, not even potentially. Earth barely produced enough food, clothing, and medicine to satisfy a quarter of its own population. And what it manufactured was of such low quality that it couldn’t compete with the worst, cheapest products of Xenoid technocracies. There was little use for earthly products, except as folklore and tourist trinkets.

For commercial expediency, they turned the Earth into a souvenir-world: another of Jowe’s phrases.

Because, no matter what the ads said, Earth was no paradise. Getting by was a day-to-day struggle. For every person like her who lucked out, thousands more people were left by the wayside. Like Yleka. Like Jowe.

Buca was almost sure that the real reason Jowe was arrested and sentenced had nothing to do with the Xenophobe Union, but something else much more petty. Until they caught him, Jowe was a freelance “protector.” And one of the best; he raked it in. The protection racket was theoretically illegal, but it could be even more profitable than being a social worker. Riskier, too; if a freelancer got sloppy about paying off the Mafia, the Triads, or the Yakuza every month, tough luck. If Jowe had given her a half-price discount in rate just two months after he’d started protecting her, only because he’d fallen in love with her beautiful eyes, maybe he’d been naïve enough to do the same for others. Too dangerous. Organized crime didn’t like it when other people gave away their money. The arm of the Yakuza was as long as Planetary Security’s—and they were tougher when punishing time came around.

The truth of it was that she hadn’t tricked Jowe. He had set his own trap. The overly idealistic kid believed that sex, cuddles, and sweet talk meant she loved him, too. She didn’t force him to do it. He was just trying to do her a favor, relieve her debts. She had liked him, but… Love your neighbor as yourself—but not more than yourself. Even though Jowe was one of the few men who had known how to treat her like a human being, not like an expensive toy with holes. He spoke to her mind. He was tender and patient.

She’d never forget that last look he gave her when Planetary Security came to take him away. A mute plea not to forget him. The leathery face of the sergeant who arrested him—the face of a man who’s seen it all and doesn’t believe in anything anymore. Something like a knot formed in her stomach.

She gulped. Yes, it had been a sign of weakness—but it was the least she could do for him. She never could have made it without him. Without what he had saved her in protection money, she still wouldn’t have enough to buy the translucent leather dress that showed off her healthy animal body and her slender muscles to such advantage. And Selshaliman would never have noticed her at that party.

Getting picked by a Grodo was one of the surest ways of leaving Earth—and one of the hardest. Other than luck, it required absolute health. Zero cosmetic or medical implants. Zero genetic or psychological disorders. Zero drug consumption, not even the soft stuff. Even when Yleka made fun of her, she always faithfully kept to her daily exercise routine, and she detested the facile escape of artificial paradises. Chemical and electronic drugs went in and out of fashion. More and more expensive all the time, but always leaving a trail of incurable addicts in their wake. Telecrack yesterday, neurogames today, who knows what tomorrow. It was easier to replace one addiction with another than to recover.

Buca gave a pitying look to several boys hooked up to consoles. Neuroplayers. Isolated in the private worlds of their direct-access cortical implants. Rich kids, you could tell. By their tailor-made clothes and the fact that no burned-out street neuro would have access to the middle ring of an astroport. These guys had to have enough credits in their accounts to bribe the Planetary Security men. And to pay for hours, not just minutes, of time in play-cyberspace, where they could forget they were living on a planet with no future and a repulsive present.

Their philosophy was sound and darkly attractive: reality is shit—run away from it. In the virtual world, time moved at a different pace. In it they could travel to planets they’d never see. In it they could be superheroes. Invulnerable Colossaurs, or beautiful, feline Cetians. Why risk real death by fighting with the morons of the Xenophobe Union for Earthling Liberation? In neurogames, they could enjoy a thousand synthetic deaths a day and liberate the Earth from the Xenoid yoke a thousand times.

Convulsing with laughter every time they looked at each other, three authorized social workers passed by, swaying to the effects of what was no doubt one of the first times they had tried telecrack. Buca thought of Yleka. This is how it must start… Telecrack was incurably addictive. Supposedly it heightened your telepathic potential, letting you establish temporary bonds of empathy, even exchange isolated thoughts with others. According to Jowe, that was all bunk. Human beings lacked telepathic receptors, and nothing could change that. The only effect of telecrack was to overcharge your neural circuits and cause hallucinations. Period.

Yleka used to take a dose before starting with each client. She said it “tuned her in,” and she claimed she worked better that way. Maybe it was true, for the first two or three hours of the night. Later on she always ended up bawling and babbling incomprehensibly about someone named Alex, “who was working on something hush-hush, very important.” Her friend’s secret bothered Buca a little at first (she had told Yleka her whole life story), but she soon came to the conclusion that this Alex was just another dumb and meaningless lost love. And all that about his “important hush-hush work,” just Yleka’s romantic idealization.

Being a social worker had several things in common with being sentenced to Body Spares. In either case, a girl wasn’t in total control of her body.

Poor kid, she must have loved him a lot if she was turning to telecrack to try and forget him. Though perhaps the horse-pill doses she consumed were just an attempt to get out of her own body while she was being subjected to all sorts of degrading manipulations. Being a social worker had several things in common with being sentenced to Body Spares. In either case, a girl wasn’t in total control of her body.

Yleka took the slow road to self-destruction. Her body deteriorating from addiction, she reached the inevitable moment when she could no longer attract clients the way she once had. At least she managed to get that Cetian, Cauldar, to take her, and she left the planet with him. Where could she be now? And how was she?

Cetian humanoids were the galactic species most like Homo sapiens. But more beautiful, more seductive—and more dangerous. Males and females roamed Earth, searching for candidates for their slave brothels. They paid very well. And nobody made love like they did. Buca had come this close to leaving with Yleka, going off with her and Cauldar. But she had decided to take the rumors seriously.

There were horrible stories going around about the dives of Tau Ceti. About girls forced to couple unnaturally with the polyps of Aldebaran or the segmented Guzoids of Regulus, leading to their death, mutilation, or exotic, repugnant, and incurable venereal diseases. And there were worse things than the slave brothels. Rumors told of lots of young people, seduced by the Cetians’ angelic looks, who ended up on the organ traffickers’ chopping blocks.

A lot of those stories must have been made up. How could humans be of any interest, even zoophile interest, to beings that reproduced asexually, like polyps or guzoids? But after considering that there’s usually a kernel of truth in every rumor, at the last minute Buca had let Yleka leave by herself. Her friend, in a best-case scenario, would now be subject to Cauldar’s every whim. All Cetians concealed an implacable iron will under their sweet external appearances.

A real pity: before she had filled herself with drugs, Yleka had had an enviable body. Maybe Selshaliman would have taken both of them. For a Grodo, two would do better than one girl alone.

Almost without her realizing it, they had entered the inner ring of the cosmodrome, reserved strictly for arriving and departing passengers. The Grodo’s movements had grown calmer. He was much more familiar with this area, and he felt safer here than outside.

Though only a human who hated his fellow man would attack an insectoid. The only time a Grodo had been the innocent victim of a group of armed robbers, the geophysical weapon had spoken again and New London disappeared, swallowed by a tsunami. Lesson learned. Grodos could travel safely anywhere on the planet.

Moreover, if anyone were crazy and suicidal enough to try harming one of these insectoids, he’d find it a hard job to pull off. Selshaliman’s shining chitin carapace was practically invulnerable to every sort of projectile, and it was absolutely forbidden to own or manufacture energy weapons on earth. Planetary Security agents and their mini machine guns made sure that rule was scrupulously followed.

Armored, with four slender but incredibly strong arms and four matching legs, Grodos were rapid fighters, whose strength was second only to that of the massive Colossaurs. Besides, they had those stingers, good for injecting lethal venom into their victims.

And for doing other things, as Buca knew too well.

The inner ring of the astroport was empty of any sort of cyberaddict or social worker. Only travelers had access to this zone. Out the large windows you could see the runway, with the shuttles waiting in an orderly line, broken here and there by the occasional squat, aerodynamic suborbital patrol ship. Buca smiled, amused: it appeared that, despite all of Planetary Security’s boasts about “maintaining control,” the problem of illegal departures from the planet kept getting more and more serious. They’d had to buy so many of these ships from the Xenoids to control the fugitives that their own astroports weren’t enough to serve them all.

Buca had never entered an astroport’s last ring before. The simple fact that she was able to walk through these corridors was almost a guarantee that Selshaliman would make good on his promise. That she would be boarding the shuttle, and then the hypership, leaving Earth. Forever.

Nostalgia invaded her.

She remembered her birth on the small island whose name she preferred to forget. Her mother, happy to finally have the daughter she had wanted, baptizing her with the name María Elena. Her father, a bearded astronaut in the satellite-hunting patrol, only an occasional presence at home, between one trip and the next. She remembered her childhood, free of poverty, free of dependence on Social Assistance, believing that Planetary Security agents existed only to protect her. Believing in terrestrial hospitality and the goodness of Xenoids. And her mother, looking at her and sighing, as if to say, “Play and enjoy life now. There will be plenty of time for suffering later.”

And there was.

But nobody could take those years of happiness away from her.

Later, everything came all at once. When she was ten, she discovered the lie of the Galactic Protectorate, the cruelty of the Ultimatum, what Xenoids really were. Her birthday present had been a one-week trip to Hawaii, all first class. They even went to the astroport to take the suborbital shuttle. She’d loved it! Never suspecting that it would be the last time her whole family would be together. Her mother and father cried the whole time, whenever they thought she wasn’t looking. They were hugging, and Buca couldn’t understand why.

Until, after they had been sitting for hours in the cosmodrome waiting area, officials from Social Assistance came to pick her up. And she knew she would never see her parents again.

Driven to the brink by their mounting debts, her parents had sold themselves for life to Body Spares. In return for that farewell trip, and for a clause guaranteeing room and board for their daughter until she turned fifteen. And also for canceling the debt she would otherwise have had to pay in her parents’ place, which would have made her a lifelong slave of the Planetary Tourism Agency.

She never forgave them.

Boarding-school hell, surrounded by kids rescued from the streets and marked for a life of crime almost from birth. A happy and sheltered childhood was a handicap there. Common girls, who had grown up keeping their distance from the turf wars between the Yakuza and the Mafia and making fun of the Xenoids who prowled for healthy young native girls, had a mean streak that she lacked. They were as strong and aggressive as wild animals, and they hated and envied her for not being one of them. For being good-looking and having manners, for being tall and strong-boned. They hated her and they let her know it. Humiliating her. Hitting her.

It was hard. But she adapted. Learned. Toughened up. So when the money that her parents (long dead, both driven insane) had gotten from Body Spares ran out, she ran away from boarding school before other people could decide what to do with her. She already knew what she wanted: to leave Earth, no matter the cost. She had no talent for art or sports, and nothing beyond basic education. And she sure wasn’t going to risk her life on a wild kamikaze attempt at an unlawful space launch.

She knew what the surest way was to carry out her plan: become a freelance social worker and get a Xenoid to take her. Galactic tourists really seemed to appreciate the sweetness and good cheer of human females, and especially their ability to pretend that their relationships were not mercenary.

Without documents you could never become an authorized social worker. One of those who turned over part of their earnings to the Planetary Tourism Agency and in exchange got protection: a minimum salary, guaranteed retirement, and free medical care. Nor did she want any of that. Her way was to get by on her own or perish.

She screamed, but the hotel rooms were soundproof, or else the human employees were used to the screams of social workers.

At first it seemed she wouldn’t make it. Her first client, a deceptively friendly Centaurian, insisted on the full package in his hotel room. And she, being treated like a lady for the first time in her life, naïvely agreed.

The Xenoid kept going and going… And the act became a torture session that went on for hours. She argued, kicked, and clawed, trying to get away, to no avail; the Centaurian was much stronger than she was. She screamed, but the hotel rooms were soundproof, or else the human employees were used to the screams of social workers. Nobody came.

The interminable and sadistic coupling finally made her faint. She ended up swollen, turned to jelly, aching for days. The worst of it was that the bastard had taken advantage of her unconsciousness not only to sneak off without paying but to steal what little she had saved, too. And he hadn’t even paid the hotel bill.

After being robbed three times by amateur thieves, she contacted the pros: protection was expensive, but it worked. They never cornered her in a dark alley again. Or made her turn over her hard-earned wages at the point of a vibroblade. Or forced her to give herself up.

Now she had triumphed. If she wished, she could return anytime and walk haughtily through the seedy byways where she was once nearly a slave. If she wanted. But she planned never to return.

A teletransport booth opened right in front of her face, startling her. A Grodo insectoid emerged in a gust of cold air. Apparently coming from some city in the far north. She looked with curiosity at the empty booth. She’d never seen one so close, much less used one. They were colossally expensive. Completely beyond the reach of freelance social workers.

It was time she started getting used to them. All the Xenoids used them when they were in a rush. You got in, a flash of disintegration—and you showed up, with another flash, in a similar booth thousands of miles away.

You could only use them to get around on the same planet, and they made small and regrettable mistakes on rare occasions. Very rare occasions. For example, the Grodos’ private network had never had one of the accidents that periodically occupied the news holovideos.

The Planetary Tourism Agency always compensated the family members of the unlucky victims of dematerialization, giving the evergreen excuse that on Earth they didn’t have enough experience managing such advanced equipment, because extraterrestrial technicians were reluctant to train human crews to run teleport booths. Maybe there was a bit of truth in that. Surely newly trained human teletransport specialists would get off the planet as fast as they could: artists, scientists, athletes—they all ran from their birth world as soon as extraterrestrial credits made them understand where true happiness could be found.

Of course, they never stopped shooting their mouths off about Liberating the Earth, Fighting for the Rights of the Human Race, and other such hot-air slogans. Buca despised them. It was so easy to talk about ideals from the outside, on a full stomach. And so hypocritical. She’d never make fun of the people who stayed behind on Earth, and she’d never “show solidarity with their just struggle.”

Three isolated bangs.

Then the too-familiar rattle of small-caliber automatic arms.

Buca was stretched out on the ground before she understood what was happening. Her reflexes had betrayed her; you’d never survive in the suburbs if you insisted on standing after you heard shots fired. Mildly annoyed over her broken dignity, she watched.

The Planetary Security men were cornering a lone terrorist. He was jumping from column to column with incredible agility, evading them and firing a prehistoric repeating rifle. Doubtless he had an enormous dose of feline analogue in him, a non-addictive military drug that endowed any human with the legerity and fast reflexes of cats.

The Xenophobe Union for Earthling Liberation guys often used it on their commando operations. The side effects were devastating exhaustion and depression, which left you totally defenseless. But a new dose would eliminate those effects. You could keep up the cycle indefinitely, or until you perished, all your physical and mental reserves drained, active to the last second.

Beaten by numerical superiority and better arms, the man fell, hit point blank by the Security agents’ bursts of fire. They kept on firing until unrecognizable remains were all that was left of the body. The feline analogue also made you incredibly resistant to wounds. More than one agent had discovered that a terrorist with a dozen shots to the chest could still open his belly with one blow.

When the astroport clean-up people picked up what was left of the body and traffic returned to normal, Buca got up and glanced around, looking for Selshaliman. She suspected last-minute betrayal. That would have been the height of irony, to leave her stranded there in the middle of the astroport.

“Your identification, please,” the Planetary Security agent’s voice resounded behind her, a mix of courtesy and authority. The barrel of a gun, still hot, poked insistently at her shoulder.

“I thought freelancers weren’t allowed in here.” There was disdain in the voice that emerged from beneath the helmet. “Pretty dress. Too bad a monkey’s still a monkey, even in a silk dress. Come along with me. You and I are going to go clear up a few things in private. And you’d better be very nice if you don’t want me to accuse you of being that poor moron’s accomplice.” He pointed with his machine gun at the pile of scraps.

“Wait, you’re making a mistake, I came here with—” Buca tried to explain, trembling with fear and rage. That was the usual deal the Planetary Security guys offered women in her profession: sex for impunity. But how had he recognized her in spite of her expensive dress? She suddenly felt as naked and vulnerable as when she used to go around dressed only in a translucent jacket and a scanty fluorescent loincloth.

“I don’t care who you came with. You’re coming with me, princess,” he interrupted her. And he stuck out his gloved hand to grab her brusquely by the arm. Buca closed her eyes and cringed, like a child waiting for his father’s belt to strike. Where had Selshaliman gone? Had it all been a dream?

Zasss… The sound, right next to her, like a whip. Something fell, over there.

The gloved hand never touched her. She opened her eyes.

Selshaliman was at her side, antennae up and the light reflecting wonderfully off his faceted eyes. He had never looked so beautiful to her before. The Planetary Security agent, sitting on the floor several yards off, rubbed his aching chest.

“Are you all right, Buca? Did he hurt you?” the insectoid’s vocal synthesizer chirped.

“Believe me, we are very sorry for this…incident. She is perfectly fine. My man didn’t even touch her. We didn’t know that she was with you.” The voice of another Planetary Security man, a sergeant, judging by his stripes, sounded conciliatory. “To make up for your trouble, we’ll give you top priority on the shuttle.”

“You had better do so. Come, Buca,” Selshaliman said majestically, barely touching her. Buca leaned on him. At that moment she could even have loved him.

He’d hit a Planetary Security guy just to protect her! The sergeant and his man were nothing but trash to a tourist, especially a Grodo, but it was the gesture that counted. She walked on Selshaliman’s arm.

“She’s going to be incubated, and that makes her a thousand times more valuable than you or me, or a hundred of us.”

But she didn’t move away fast enough to avoid hearing what the sergeant said while he was helping his buddy back to his feet. Or maybe he said it so loudly on purpose: “Come on, to your feet, stupid. He hit you hard, but your armor absorbed it well enough. And you know what? You deserved it for being an idiot. For not paying better attention. That’s not any old social worker. The Grodo has picked her; she’s going to be incubated, and that makes her a thousand times more valuable than you or me, or a hundred of us.”

Buca didn’t want to hear any more. But Selshaliman’s measured pace allowed her to hear the rest, too. The expert sergeant explaining things to the rookie. What she had known from the beginning. What she’d rather not remember.

The sergeant had a decidedly disagreeable laugh. “Grodos are hermaphrodites. They only reproduce once, and then they die. But they have to deposit their eggs in another living being. The ‘incubator’ has to be warm-blooded and as intelligent as possible. I guess that’s so she won’t kill herself, like a sensible wild animal would do if it saw it was as good as dead. She’ll last long enough so the eggs can hatch and the larvae can eat her guts. And apparently we human beings, especially if we don’t do drugs or have implants, are perfect fits. From the color of its carapace, it’s got to have a few more years to go. Our girlfriend will have everything she wants until he-she feels it’s time to worry about the continuity of the species. And I wouldn’t want to be in her place then…”

Buca couldn’t take it anymore. Removing her arm from Selshaliman’s, she gave a half-turn and confronted the sergeant.

The man had already taken off his helmet. Those leathery features… Buca gulped, recognizing him.

Those eyes, sick of seeing all the world’s misery, gave her such a look that she was only capable of muttering, indistinctly, but with a calm that she never would have thought herself capable of:

“True. But I’m leaving, and you two are stuck here.”

And she went back to her Grodo lord and master. Anger and impotence burned her eyes. Fortunately the makeup she had on was waterproof. Tearproof, too. And it formed a veritable mask over her face. The day they took Jowe away, she hadn’t been wearing makeup. It wasn’t likely the sergeant had recognized her. Even so, the prudent thing was to get away. As soon as she found an opportunity, she would beg Selshaliman to use his influence to have him punished, somehow. She was sure he’d do it, to please her. Just thinking about this, she could feel the calm returning. Though maybe she would be coming down too hard on the man—he seemed to know a lot about Grodos, and he had confirmed what Selshaliman had told her: until his grayish carapace turned completely dark, the time hadn’t come yet.

Several years. What would it be like? The ovipositor stinger, smoothly and painlessly penetrating her to deposit its precious cargo. It could even be pleasant. And the eggs, so delicate they sometimes took years to hatch—and for some girls, they never did. Maybe she’d be lucky, like she’d been so far. Or maybe she could even, with some metabolic poison…

She looked at Selshaliman out of the corner of her eye and went back to repeating the catchy lyrics of the technohit in her head. Better not try anything. Better not even think about it. If the Grodo suspected she’d even considered such a possibility, he’d drown her in acid. Or worse.

It’d be better to resign herself to the idea right now. After all, she had enjoyed the best part of her youth. And as the saying goes, die young and leave a beautiful corpse. It wouldn’t hurt; from what the Grodo told her, the larvae secreted a very powerful analgesic. She’d enjoy it all right up to the very end, with the same dying vitality as a guy doped up on feline analogue.

And how she’d enjoy it! All of her worldly desires would be fulfilled. It was hard to imagine how big Selshaliman’s fortune was. In any case, more than big enough to buy the most exotic delicacies, to travel to the most exquisite and fashionable resorts. She’d have all the lovers she wanted. She’d already talked it over with the Grodo: the very concept of faithfulness made no sense to a hermaphrodite being. She would even be able to afford to take one of those pale, perverse, and beautiful Cetians. She’d only be forbidden to have children, to protect her precious womb. But who would waste time giving birth?

She’d learn to present herself well in galactic high society, to which Selshaliman would be delighted to introduce her.

Of course, it was about time she convinced him to dump that horrid Arab name of his. He needed something more modern, something to impress her girlfriends with. Because he was going to pay to have some of them travel from Earth. And maybe, if he was still alive, Jowe. She owed him that.

Smiling, Buca walked through the last doorway in the astroport and boarded the shuttle that would take her to the orbiting hypership.

A Japanese name would sound nicer. They were all the rage now. Four syllables, the way they like. Horusaki, something like that. It was important to pick one, as soon as possible.

Yoss was born José Miguel Sánchez Gómez in Havana in 1969. He assumed his pen name in 1988 when he won the Premio David Award in the science-fiction category for his first book, Timshel. Since then, he has gone on to become one of Cuba’s most iconic literary figures—as the author of more than twenty acclaimed books of sci-fi and realism, as a champion of science fiction through his workshops in Cuba and around the world, and as the lead singer of the heavy metal band Tenaz. A Planet for Rent is the inaugural title in Restless Books’s Cuban Science Fiction series, launching digitally in the fall of 2014. Find more info at restlessbooks.com.