Courtesy the artist and Monya Rowe Gallery, New York

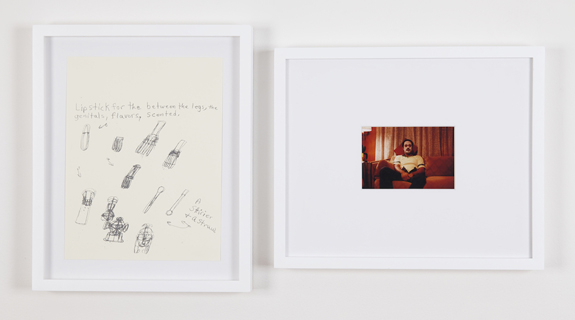

By age ten, artist Jacolby Satterwhite knew his mother was different. Debilitated by schizophrenia, she stayed home, unemployed from the time Satterwhite was a young child until his teenage years. Inspired by late-night television commercials promising millions of dollars for inventions, she frantically drew an array of pencil-on-paper diagrams and product ideas. To her, these drawings offered a path to financial self-sufficiency. Satterwhite spent his early childhood sitting next to his mother, trying to help her reach this goal.

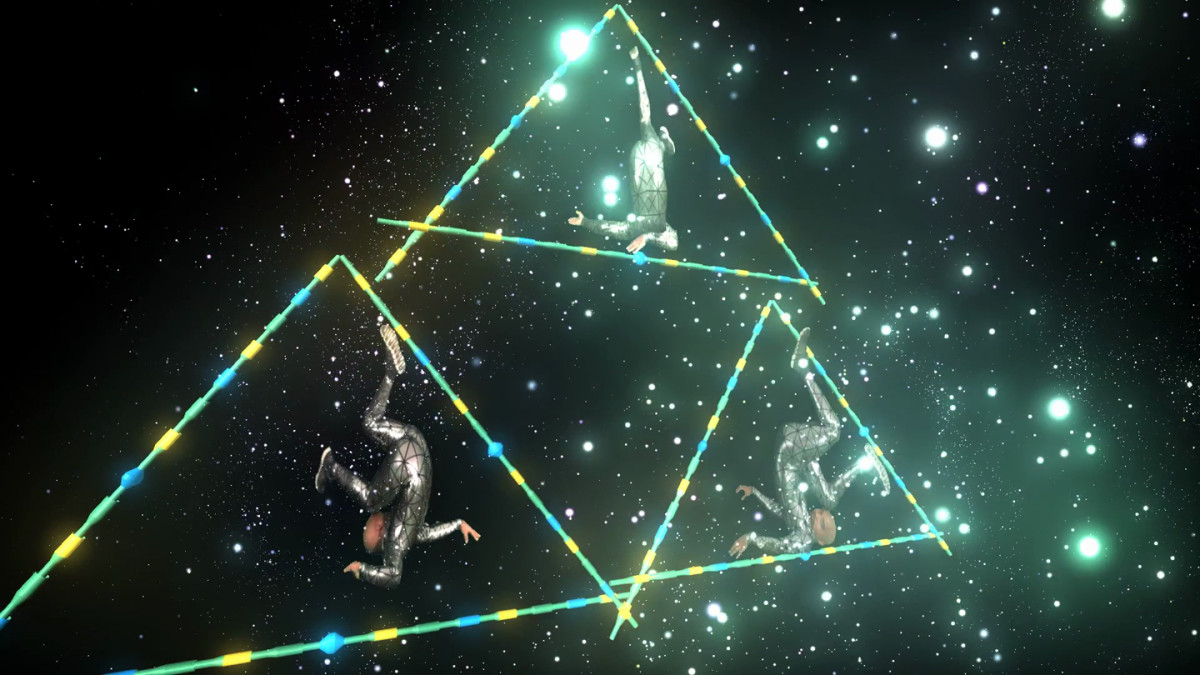

Satterwhite now makes three-dimensional worlds out of his mother’s graphite work. He starts by taking her linear works and individually hand-tracing his mother’s drawings with a cursor or stylus in a 3D-rendering program called Maya then places the drawings within a larger virtual landscape, pairing them with family videos, photographs, dance, and performance. The resulting piece–a whirlwind of floating photos, 3D drawings, the artist dancing and acting, and family footage–culminates in a video experience that explores the boundaries between reality, narrative, psychology, surrealism, and memory.

His solo exhibition, The Matriarch’s Rhapsody, is on view at Monya Rowe Gallery in New York from January 5 to February 16. I spoke to the artist as he was gearing up to install the show.

—Haniya Rae for Guernica

Guernica: Has your mother been dealing with schizophrenia her entire life?

Jacolby Satterwhite: I wasn’t aware of it until I was ten years old. She had been drawing since I was six or seven as a result of unemployment. The Home Shopping Network or paid programs that aired on late night television in the ’90s inspired her to draw inventions. The jargon in the commercials would include things like, “you could become a millionaire easily if you come up with a great idea.” It was her pursuit of money and self sufficiency that got her obsessively into drawing.

As a kid, I was watching that, and I believed it. I wanted to help her so I learned how to draw. She had crazy glitter crayons–every brand. It was a strange laboratory.

She became my institution, my rubric, my system to find confidence in a larger, interdisciplinary, surrealist practice.

As I got older, I went into my own world of video games, watching music videos, drawing, and painting. She continued drawing, but I didn’t pay any attention to it. Eventually her illness became recognizable and full blown.

I didn’t recognize the sophistication and beauty in her drawings until the latter portion of undergrad. I kept them around for inspiration.

I attended art school from ages fifteen to twenty-four, and followed up with six artist residencies. My mindset often feels shaped by institutional rules and anxieties. Watching my mother work from a place of necessity was inspirational for me, and I felt like I could learn more from her than from those spaces that I constantly put myself in. She became my institution, rubric, and system to find confidence in a larger, interdisciplinary, surrealist practice.

Guernica: You collected all of these images and diagrams from your mother over this period of time. When did it occur to you to start using them in your own work?

Jacolby Satterwhite: Do you know Derrick Adams? He’s an artist. He used to curate Rush Gallery. He was teaching at the Maryland Institute College of Art for a semester or two, and one of the things he wanted us to do was, “Bring in something that you don’t think is art, that’s personal to you, that’s something about yourself you don’t tell anyone.” So I made a video collage that’s similar to something I’m going to show in my solo show, where I pair family photographs and objects that come from my mother’s drawings.

A family photograph is a documented performance…

I went into the my attic, and I found hundreds of family photographs—all those pots and pans and plates and blankets my mom drew from memory; it was kind of like a retrospective of those things, documented in photography by my father. It was this weird domestic appendix. When I started pairing those things and showed it to everyone, I realized the practice had a power to it. It came naturally to me, and the feeling I got from showing that work was so rewarding. The first thing I thought of was that it should be a performance score, because the drawings look like these weird directions and diagrams with objects, and they show how objects influence the body and how they influence the body within a photograph. A family photograph is a documented performance, but a real-life performance. So, I tried to bring that into the present.

I realized I wanted to make something more epic and surreal, like my paintings. When you work in a medium, you learn how to bridge ideas with content and form. The form informs the work. I was learning Maya, and there’s a technique with rotoscoping and tracing where I could trace her drawings and lines and make them into real things. That’s when I thought about making these meta-narrative worlds—large, expansive Polly-Pocket landscapes—and have long epic performances. So, I basically developed a virtual-reality world, based on a utopia she wanted.

Guernica: Does your mother help you create the work now?

Jacolby Satterwhite: Her drawings are a consistent platform for the beginning of many of my projects.

Guernica: But is there a dialogue between you and your mother during the creation of the piece?

Jacolby Satterwhite: It’s more complicated than that because it’s hard to… I check on her all the time, but I don’t go home a lot. When I go home I show her what I’ve been doing, and she laughs. As my body of work begins to grow and evolve, she gets more confused by my responses to her drawings. She’ll look at my animations and performances and say, “I never drew that. This is yours.” She loves that she’s a part of my life.

Guernica: Has incorporating your mother’s work into your art helped you to understand her better?

Jacolby Satterwhite: Yes, because of the tactility of the whole thing. I traced two hundred thirty mugs for “Reifying Desire.” It took eight or nine hours, tracing each drawing. I learned her hand, her habits, the phalluses and penises that are embedded in coffee mugs and everyday objects. I learned a tremendous amount about her. I put her on an extremely high pedestal among artists because of the inventiveness and genius in the drawings.

Guernica: To what extent has your experience with your mother shaped your general thoughts on the way the mentally ill are treated in this country?

Jacolby Satterwhite: Well, being in New York is profoundly sad because there are so many homeless, mentally ill people. Seeing them reminds me of my own reality, and that is really hard and painful. I think about what would happen if she didn’t have the people she loved around her. That scares me. I don’t like mental institutions, or at least the ones that I saw when I was growing up, because patients are not treated well. I’d rather see my mother happy in her home, dealing with it naturally, without drugs. You learn to love someone in their new way of performing in life.

Jacolby Satterwhite received his MFA from the University of Pennsylvania and his BFA from Maryland Institute College of Art. He’s been a resident of Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Fine Arts Works Center, and The Center for Photography at Woodstock. Group exhibitions include The Studio Museum in Harlem, Contemporary Arts Museum of Houston, Exit Art, The New Museum, The Kitchen, MoMA PS1, and the Smithsonian Institution.